By Christian Heller

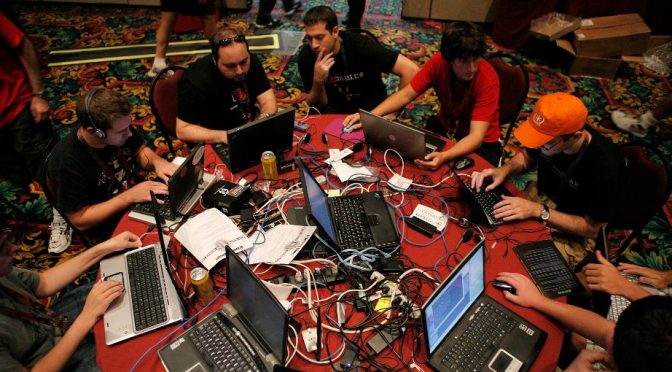

The U.S. defense complex is looking to private industry and civilian research to gain an advantage on the battlefield as advanced technologies push warfare in new directions. In cyber capabilities especially,the U.S. and its naval services lean on civilians, contractors, and independent cybersecurity companies to gain a competitive national edge. Every year these groups descend upon Las Vegas, Nevada for back-to-back information security and hacking conventions dubbed Black Hat USA and DEFCON. The Department of Defense follows in step to search for best practices, advanced insights, experimental tools, and new talent.

The 2019 editions of Black Hat and DEFCON held plenty for national security analysts to ponder. Dino Dai Zovi, the head of mobile security at the credit card processing company Square, spoke of the need for security software with effective user interfaces which keeps pace with advances in technology. Security programs must be built for “observability” to better “understand if the protections are working and also perform anomaly detection.” Such a requirement is not only necessary for the Navy, but finds a strong historical precedent. The Navy has a long history of simplifying advanced technologies into easier, usable forms for better employment by young sailors.

Identity intelligence, one of the most utilized capabilities of U.S. forces during the past two decades of counterinsurgencies, has also been a main effort for Chinese military and government development. Researchers from the Chinese firm Tencent demonstrated the ability to spoof biometric authentication devices with common eyeglasses. They did so not by convincing the systems that the user was a different person, but rather that the user was a photo instead of a living person. Low budget defenses against identity intelligence tools may prove just as frustrating to U.S. forces in future stability operations as space blankets did against early UAVs.

Major tech leaders like Apple and Microsoft announced new measures to search externally for IT security support through the use of rewards. Apple, which normally treats its technology and systems with close-hold protections, will now award upwards of $1 million to hackers who identify critical vulnerabilities in Apple technology. Microsoft is also offering up to $300,000 to hackers who identify exploits in its Azure cloud technology systems. To facilitate this outside support, Microsoft is creating Azure Security Labs where participants can experiment on Azure networks without affecting the existing customer base.

These bounty programs have already benefited organizations like the Marine Corps which may lack the capacity or skillsets to facilitate internal network testing. At last year’s conference, the Marine Corps hosted a hacking program to test the durability of its public websites and the Marine Corps Enterprise Network, or MCEN. One hundred ethical hackers spent nine hours testing the Marine Corps’ systems and found 75 vulnerabilities in return for $80,000 in combined prize money. Though the payment pales compared to private industry awards, these events are an important way for defense agencies to engage with community experts who are willing to support the military while gaining valuable organizational knowledge in the process. The Pentagon has hosted hacking projects since 2016 and recently leveraged three security firms – Bugcrowd, HackerOne, and Synack – via contract to conduct sustained network testing. Additionally, if data scientists and cyber specialists are going to play a pivotal role in the future Navy and Marine Corps, engaging with non-traditional audiences at events like Black Hat and DEFCON help to expose the hacking world to the armed services.

The Air Force is embracing conferences like DEFCON to leverage technical expertise and open up the service to these communities. It hosted two events at this year’s conference. One challenged hackers to gain entry into an airbase, and the other tested data transfer hardware for the F-15 fighter. The Trusted Aircraft Information Download Station, or TADs, is an independent subsystem of the F-15 which helps collect sensor inputs like images. Next year the Air Force wants to bring an entire F-15 aircraft to the convention and host a hacking event involving a live satellite.

This year’s events also pointed toward the changing battlespace in which U.S. forces will operate. Harvard lecturer and fellow Bruce Schneier discussed “hacking for good,” a movement which is becoming more prevalent throughout the world. Just as military forces found themselves operating around civilians and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Iraq and Afghanistan, the future cyber battlespace may be filled with hacktivists trying to do good or “grey hat” operators taking advantage of disorder to pursue alternative motives.

Hacktivist campaigns have occurred in almost every recent global crisis including Sudan, Venezuela, Pakistan, and Libya. Hacktivist campaigns usually involve unsophisticated denial of service attacks to take down websites and servers which achieve mixed results. However, as cyberspace conflict between great powers becomes routine, such groups are sure to increase operations and become regular actors in the same competitive spaces in which government agencies and militaries interact.

Another feature of the changing cyber battlefield is internal competition between state actors. Kimberly Zenz, a senior official with the German cybersecurity organization DSCO, explained at Black Hat that Russia’s intelligence agencies and hacking organizations should be viewed as individual groups competing for influence with one another. This competition can lead to chaos and risk-taking in cyberspace as groups minimize coordination amongst one another and compete to showcase their abilities to senior officials. The results could be similar to the $10 billion dollars in damages caused by the NotPetya malware.

For the Navy, Marine Corps, and Department of Defense, the consequences of these foreign internal rivalries could be sporadic and disproportionate cyber attacks. Leaders may struggle not only to determine which actor initiated the attack, but what the target, intentions, and overall scale truly are. From the defender’s point of view, probes and attacks which could seem like a coordinated and widespread operation may instead be many. They may also be part of a concerted “persistent engagement” strategy with long-term but subtle objectives. In this case, a defender’s response could be disproportionate to what the attacker intended. These factors make deterrence in cyberspace an elusive goal for policymakers.

One final takeaway from the 2019 conventions is the intention and ability of nefarious actors to target defense users and systems outside of official government channels. Agencies may spend millions to harden networks, but users, such as service members at home, may be the greatest vulnerability in the system. They are often the softest target for foreign powers and criminal groups to exploit with simple techniques. One presenter demonstrated a fully-functioning, charging-capable Apple USB which contains a Wi-Fi implant and allows nearby hackers to access the connected computer. Another speaker showed how she used information from common online subscription services such as Netflix and Spotify to access bank accounts and personal financial data. Using common talking points, customer service helplines, and classic identity theft techniques, she was able to get access to private account information at major financial institutions without any advanced technology. A separate group, Check Point Research, demonstrated the ability to hack digital cameras to spread malware through home networks and hold personal information for ransom.

The military’s efforts to increase information technology security in the workplace may need to extend to personal services and education for service members to prevent workforce distractions, blackmail, or the further spread of malware throughout units and networks. Currently, the individual Soldier, Sailor, Airman, or Marine is the easiest objective for hostile cyber actors to target, whether for criminal, intelligence, or military purposes. The main lessons from Blackhat and DEFCON may be that nowhere is safe, and the services should explore a wider range of protection services for the users they rely on to carry out missions.

Christian Heller is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and University of Oxford. He currently serves as an officer in the United States Marine Corps. Follow him on Twitter, @hellerch. The opinions represented are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the United States Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Featured Image: DefCon attendees gather in Las Vegas to learn about new technology vulnerabilities and cyberattacks. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)