By Dmitry Filipoff

Introduction

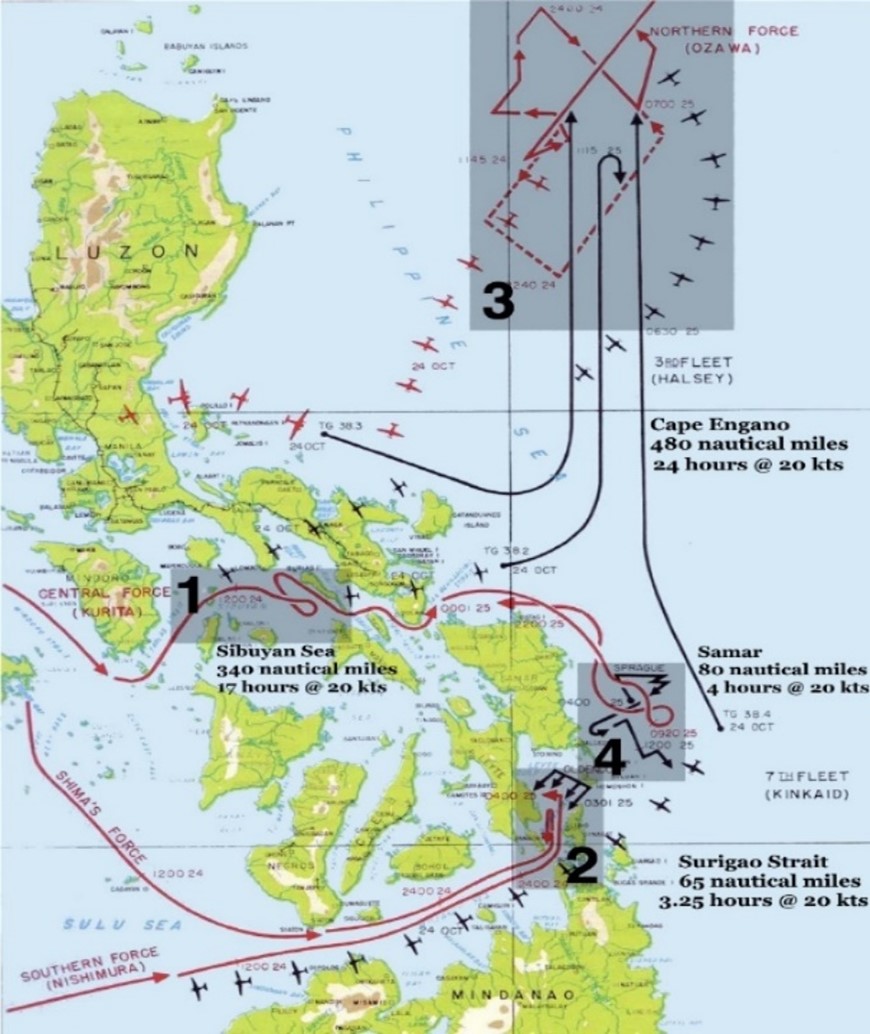

In October 1944, the navies of Imperial Japan and the United States met in the final major fleet-on-fleet combat engagement of WWII. The U.S. invasion of the Philippines prompted Imperial Japan to sortie its fleet in a desperate bid to protect vital territories and inflict a decisive blow against Allied forces.1 The ensuing battle featured separate yet mutually reinforcing clashes between multiple maneuvering naval formations. The battle ultimately resulted in a decisive defeat for the Imperial Japanese Navy, which ceased to be an effective fighting force for the remainder of the war.

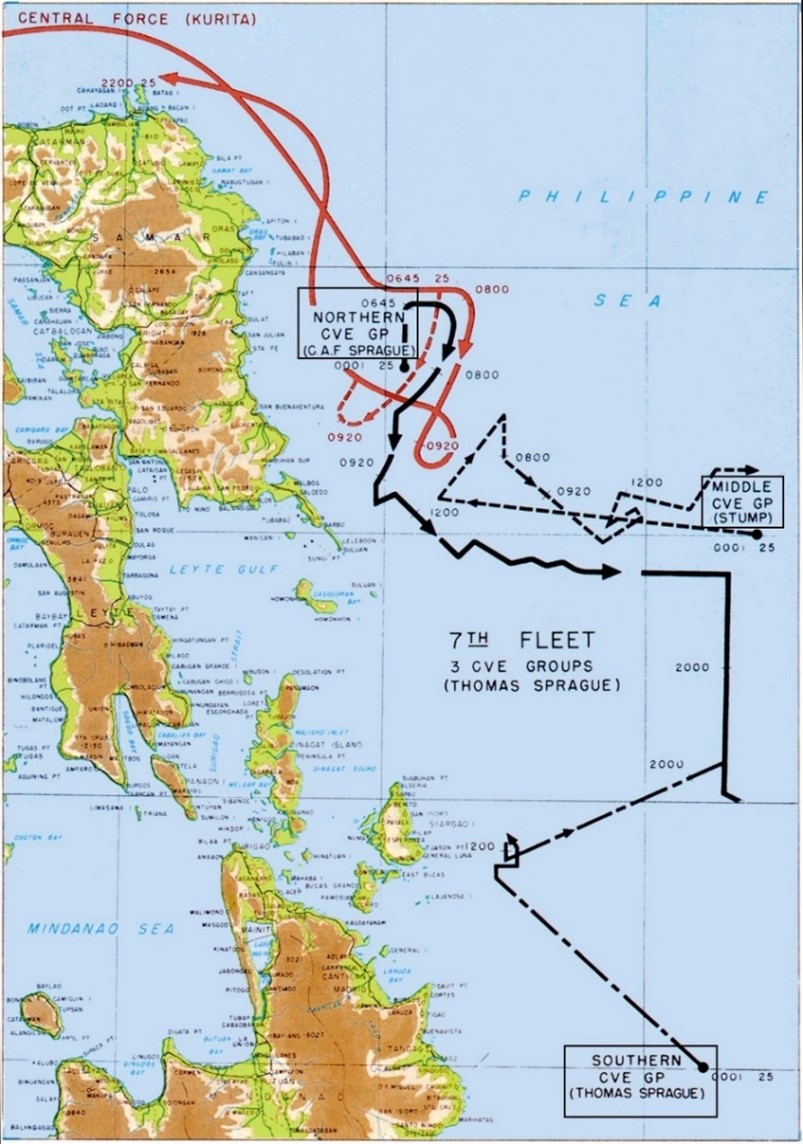

The battle triggered an abundance of controversy regarding the decision-making of the senior American and Japanese commanders. In particular, Admiral Halsey’s decision to leave the critical San Bernadino Strait unguarded afforded Admiral Takeo Kurita a fortunate chance to strike at the exposed invasion forces at the Leyte Gulf beachhead. But Kurita’s powerful force of heavy surface warships encountered a modest force of several escort carriers and their light escorts, a unit called Taffy 3. Misidentifying these forces as larger capital ship units, Kurita believed he had come across a lucrative opportunity to attack multiple U.S. Navy fleet carriers at close range. In the course of conducting a fighting withdrawal under heavy fire, the force of escort carriers and destroyers was able to divert Kurita’s attention away from the Leyte beachhead for several critical hours, eventually causing Kurita to end his pursuit and abandon the beachhead bombardment objective altogether.

What if Kurita had pressed onward toward the beachhead and ignored the forces of Taffy 3? Could Kurita have reached the beachhead and had enough time to savage the critical logistics and transports of the invasion force? Taffy 3’s pleas for help prompted multiple major naval formations to reverse course and steam toward the battle. Many of them were never able to intercept Kurita, who had already withdrawn. But if Kurita had committed to a press toward the Leyte beachhead, it would have precipitated multiple new major engagements that could have affected the broader impact of the battle. A close examination of the critical factors of time and distance outlines the kinds of clashes and tactical interplays that would have been set in motion had Kurita pressed on.

The State of Play

The Battle of Leyte Gulf featured multiple interconnected yet geographically separate naval battles occurring within the vicinity of the Philippines. These battles were separated by hundreds of miles, which constrained U.S. options for sending forces to assist the beleaguered Taffy 3. Commensurately, these distances afforded Kurita an opportunity to potentially arrive at Leyte Gulf before being intercepted by intervening forces. The specific factors of time and distance, and how they come together to dictate options for maneuvering forces into engagements, reveals an alternate sequence of events.

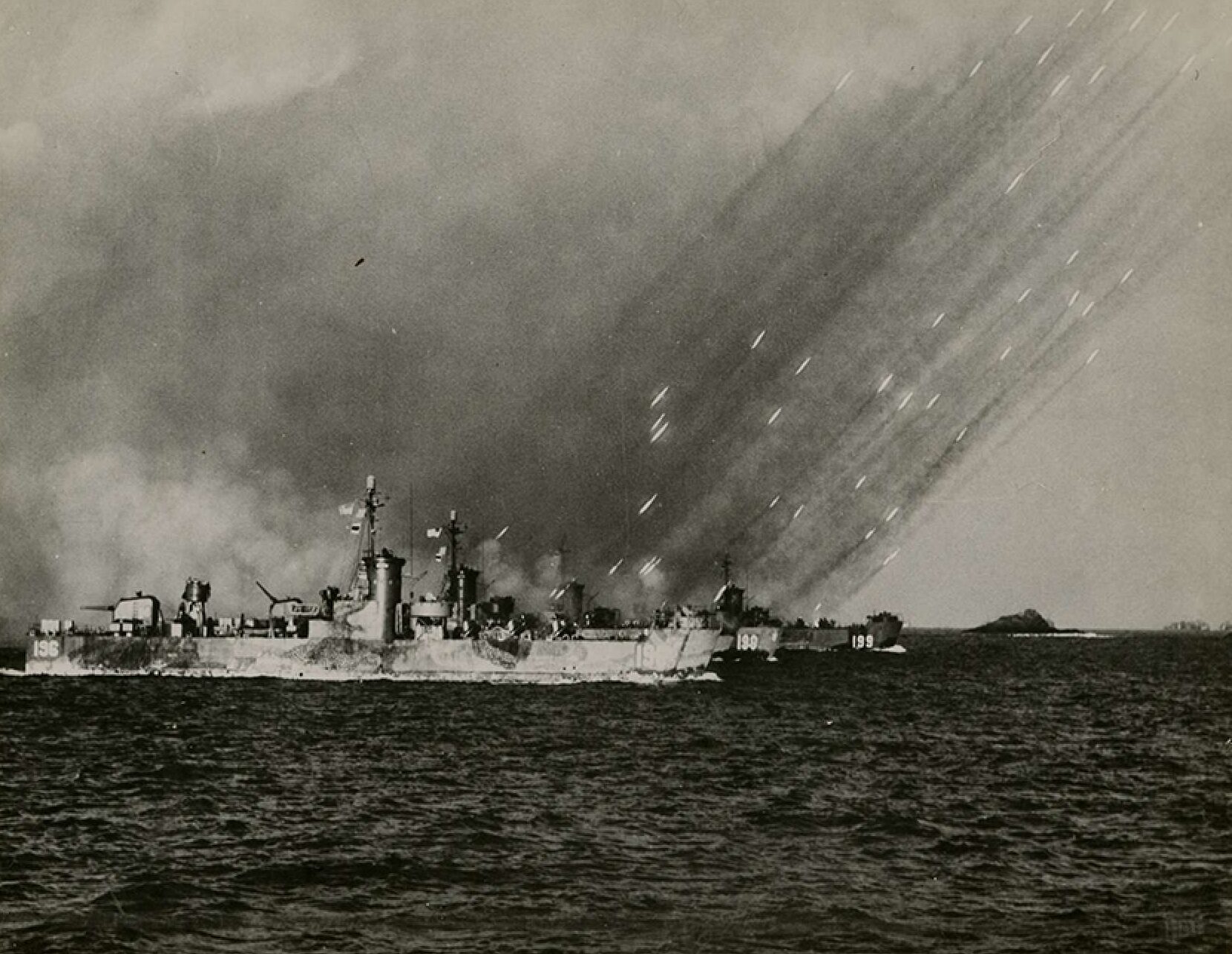

The first major battle of Leyte Gulf occurred in the Sibuyan Sea on October 24, where Kurita’s force was spotted on its way heading east to the San Bernadino Strait, from where it could then push south toward the Leyte beachhead. Kurita’s force, dubbed the Center Force, was intensively engaged by five fleet carriers and one light carrier of the 3rd Fleet.2 The Center Force suffered heavy losses, including the notable sinking of the super battleship Musashi (sister ship to the Yamato). Kurita reversed course, causing Admiral Halsey to believe the Center Force was decisively beaten into full retreat.

But later that day Kurita subsequently reversed course again and resumed his transit toward the San Bernadino Strait.3 Kurita’s Center Force transited the strait at roughly midnight on October 25.4

For a naval force traveling near the coast of the Philippines, the trip from the Strait to Leyte Gulf is roughly 260 miles (or about 225 nautical miles). Kurita’s chief of staff, Rear Admiral Tomiji Koyanagi, stated they expected to arrive at the Leyte beachhead at 1000.5 However, in post-war interrogations by U.S. personnel, Kurita indicated the night transit through the Strait occurred at a speed of 20 knots, and that the maximum speed of some of his forces at the Battle off Samar was roughly 25 knots.6 In the strait transit the force was steaming as a cohesive formation. During the pursuit in the Battle off Samar, Kurita authorized his heavy units to maneuver at will at whatever top speed their individual platforms could muster. Given the 225-nautical mile distance and a presumed 20-knot speed for formation steaming, Kurita would have more likely arrived at Leyte Gulf at around 1130.

Earlier that morning to the south of Leyte at Surigao Strait, a Japanese surface force steamed directly into an elegantly laid trap by Admiral Jesse Oldendorf. A combination of heavy surface gunfire, patrol boat attacks, and destroyer torpedo runs shattered the Japanese force at little cost to the Americans. By 0430, the Battle of Surigao Strait entered the pursuit and mop-up phase after a decisive American victory.7 Surigao Strait is roughly 60 nautical miles south of Leyte Gulf.

At the Battle off Cape Engaño to the north, U.S. forces fell for a ruse that gave Kurita his critical opportunity. The Imperial Japanese Navy had little in the way of carrier aircraft after suffering heavy attrition at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944.8 The remaining Japanese carriers were subsequently organized into a decoy force that was intended to pull the bulk of U.S. carrier striking forces away from the Philippines in a bid to open up an opportunity for Kurita to pass through the San Bernadino Strait. In this regard, the Japanese were successful, with Admiral Halsey fully committing Task Force 38 to attacking this Japanese decoy force, dubbed the Northern Force. TF 38, which operated under Halsey’s 3rd Fleet, contained almost all of the fleet carriers near the Philippines and was the Navy’s principal striking unit in the Pacific theater. Position reports put TF 38 at roughly 480 nautical miles from Leyte Gulf during the Battle off Cape Engaño.9

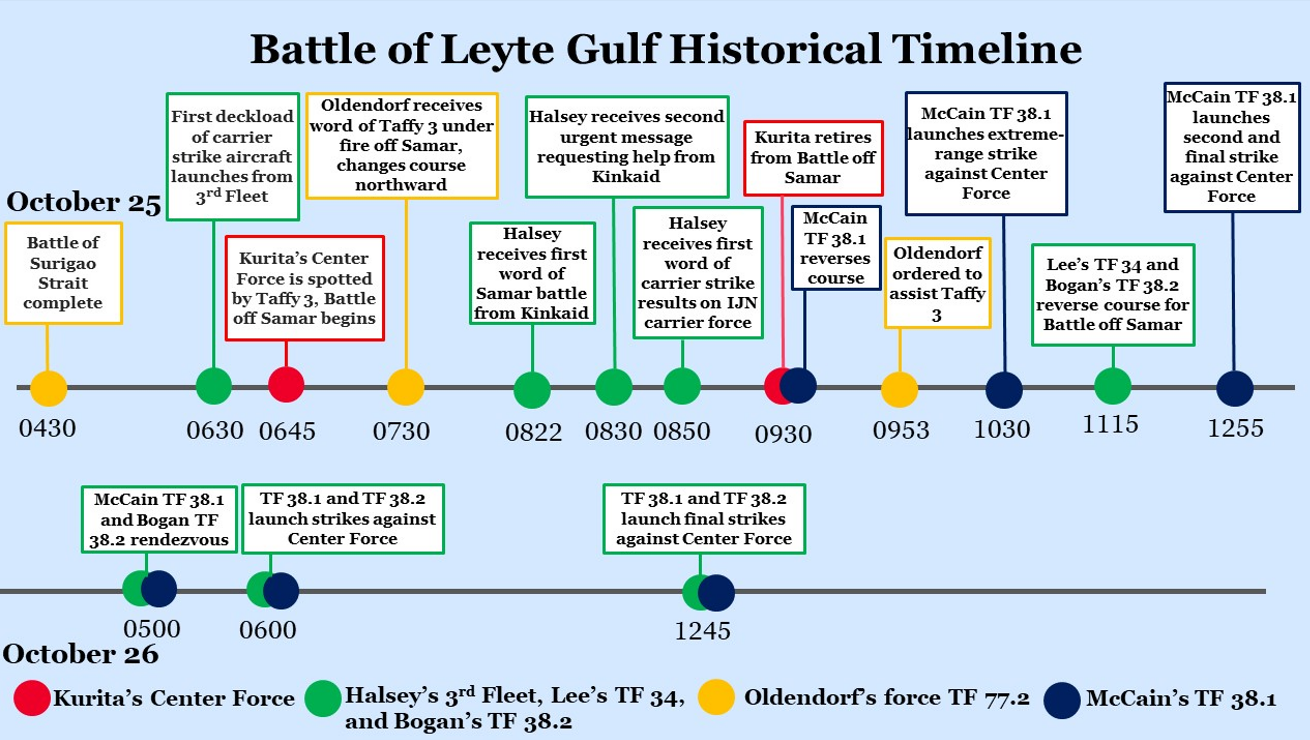

By the time Kurita encounters Taffy 3, the Center Force had transited about 60 percent of the distance toward Leyte Gulf, roughly 135 nautical miles, with 90 nautical miles to go. Kurita was sighted by Taffy 3 at around 0645.10 Here the timing becomes critical as to when various naval commanders first receive word of Taffy 3’s plight, and then either get orders to assist Taffy 3 or act on their own initiative to set course for the battle.

Admiral Oldendorf first receives word of the Battle off Samar at roughly 0730.12 Only several minutes later and acting on his own initiative, Oldendorf reverses course and starts sending the bulk of his forces northward toward the gulf.13 At 0846, he subsequently receives orders to take his entire force northward to a point near Hibuson island, and at 0953 he receives orders to detach a large portion of his force to assist Taffy 3 and send the rest to Leyte Gulf.14

Admiral Halsey’s TF 38 launches the first deckload of carrier strike aircraft at the Japanese decoy carrier force at 0630, and does not receive a report on the effects of their strikes until 0850.15 Halsey does not receive word of Taffy 3’s plight until Admiral Kinkaid of 7th fleet sends an urgent dispatch at 0822: “ENEMY BATTLESHIPS AND CRUISERS REPORTED FIRING ON TASK UNIT 77.4.3…” Halsey receives another urgent call for help from Kinkaid only eight minutes later: “URGENTLY NEED FAST BATTLESHIPS LEYTE GULF AT once.”16 Halsey subsequently receives a late message at 0922 that had originally been sent by Kinkaid at 0725, which would have been Halsey’s first notice of Taffy 3’s plight. Halsey was unable to immediately assist. With air wings already in the air and fully committed to striking the Japanese carrier fleet, and with TF 38 hundreds of miles from Samar, there was little Halsey could do to immediately assist. As he would later recall about his reply to Kinkaid, “I gave him my position, to show him the impossibility of the fast battleships reaching him.”17

Yet Admiral Kinkaid was insistent, and Admiral Nimitz at Pacific Fleet headquarters decided to weigh in. Dispatches from both reached Halsey at about 1000, inquiring about the heavy surface task force attached to TF 38 – TF 34 – under Admiral Willis Lee.18 Halsey subsequently detached this force from TF 38, and at 1115, had it reverse course for Leyte Gulf.19

After almost three hours of pursuing the retiring escort carriers at high speed, Kurita’s force began to withdraw from the Battle off Samar at around 0930.20 By the time Oldendorf and TF34 had received their orders to assist Taffy 3, Kurita was already on his way out of the battle.

Critical Factors of the Alternative

The main decision that changes in the alternative scenario is Kurita pressing onward to Leyte rather than committing his force to a pursuit of Taffy 3 that pulls him away from his foremost objective. This decision is enabled by Kurita having better situational awareness than was the case at the historical battle. Namely, Kurita accurately classifies the flattops of Taffy 3 as escort carriers, rather than fleet carriers. The critical factor of accurate classification of the ships of Taffy 3 could have enabled Kurita to press onward, and not have his ships pulled into a pursuit against marginally important targets. In the alternative scenario, Kurita’s Center Force instead preserves the cohesiveness of its formation, its southernly course, and its ammunition in anticipation of a heavy bombardment of the Leyte beachhead.

There are several other factors that are held constant in examining this alternative. Importantly, speed is held constant. All of the heavy surface and fleet carrier forces are held to be transiting at 20 knots. This realistic rate represents an effective balance between high speed, maintaining formation cohesion, and an affordable fuel consumption rate. A 20-knot speed was the Center Force’s rate of advance through the Sibuyan Sea on the night of October 24, and it was the speed of TF 34 for much of its activity on October 25.21 Using this constant transit speed figure across all heavy surface and carrier forces is useful for making a reasonable estimate of how long it would have taken each formation to reach certain parts of the battlespace and intercept Kurita.

U.S. sighting reports are held to be the same as the historical event. If not for considerable command confusion, U.S. forces would have likely spotted Kurita sooner, reacted to his force faster, and perhaps even contained his Center Force at San Bernadino Strait, similar to how Oldendorf effectively launched a devastating strait ambush at Surigao. In this alternative, the overarching command confusion that delayed the U.S. response to the Center Force is maintained.

Kurita Intercepted: The Alternative Engagement

The sequence of events develops quite differently if Kurita holds fast to the objective of attacking the Leyte beachhead. Through bypassing Taffy 3 and pressing onward, Kurita precipitates new intense engagements that likely culminate in the annihilation of his force.

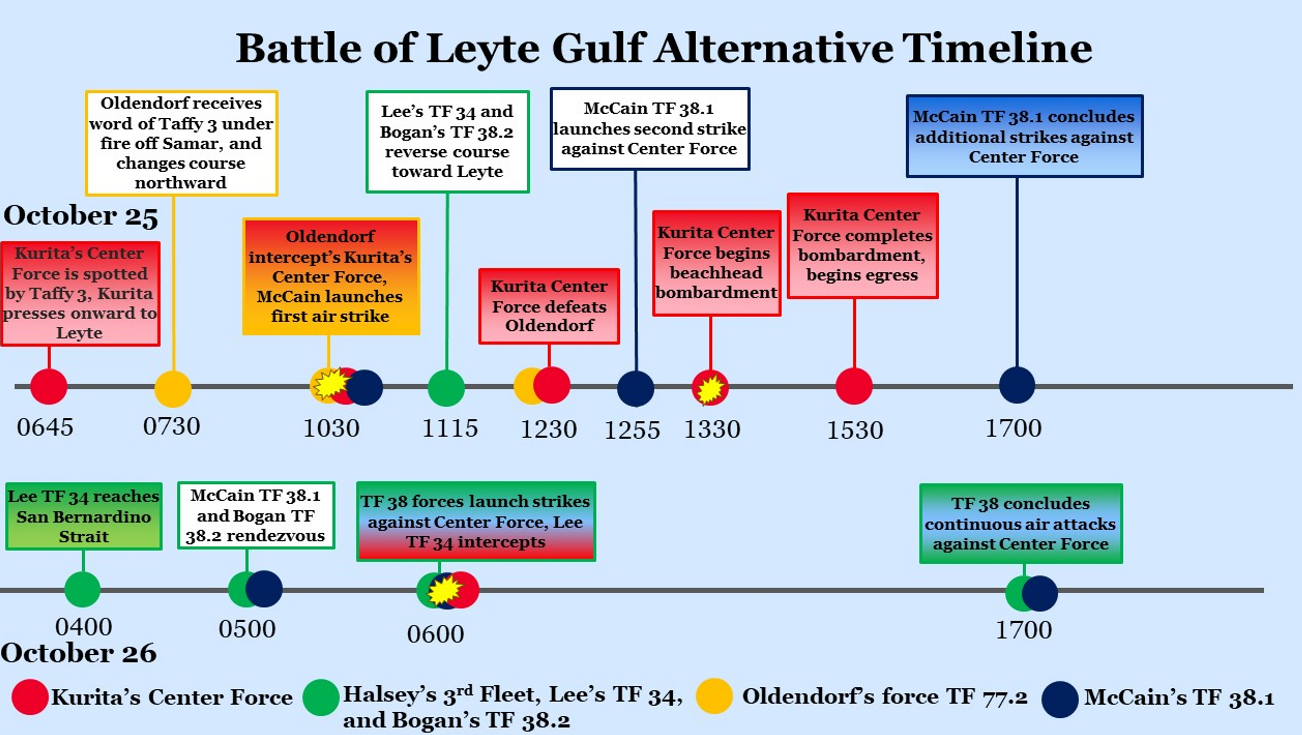

At about 0655, minutes after being sighted by planes from Taffy 3, Kurita’s Center Force opened fire on the exposed escort carriers. But now Kurita accurately classifies the warships and maintains his southernly course. At this point in the battle and at a transit speed of 20 knots, the Center Force is about 4.5 hours away from the beachhead.

Nearly three hours after the Center Force is first sighted, Oldendorf received his orders to intercept. At this point in the battle Oldendorf is already on a northward course and is about three hours from Leyte Gulf. Oldendorf is closer to the Gulf than Kurita, and likely has the benefit of steady sighting reports from Taffy aviation, which allows the 7th Fleet to maintain contact with the Center Force and provide accurate position and course reports. The combination of closer proximity to Kurita’s objective and constant aerial reconnaissance affords Oldendorf an opportunity to intercept the Center Force before it can bring its guns to bear on the Leyte beachhead. An examination of intersecting timelines strongly suggests that Oldendorf’s force would have intercepted Kurita at roughly 1030, about 20 nautical miles from where Kurita would have been able to start firing upon the beachhead.

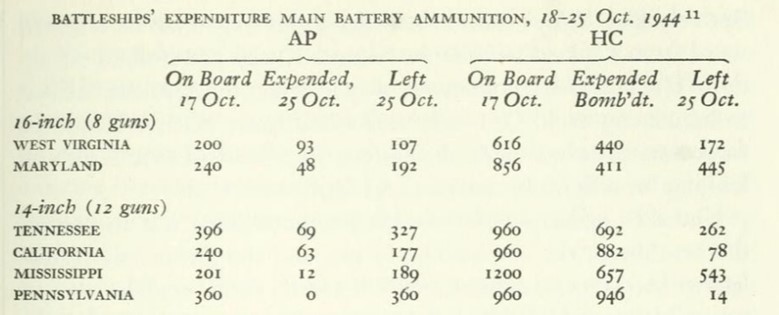

Oldendorf’s force depleted a considerable amount of ammunition during the Battle of Surigao Strait hours earlier, especially torpedoes and large-caliber armor-piercing shells.22 This issue was compounded by how the battleships had been originally loaded for bombardment missions, with nearly 80 percent of their large-caliber ammunition being high-explosive rounds, and the remainder being armor-piercing rounds. In advance of the Battle of Surigao Strait, the operational influence of this ammunition loadout resulted in Oldendorf’s command agreeing to only open fire once targets entered within 20,000-17,000 yards to offer a better chance of scoring hits.23 The fresher Center Force may have had a useful advantage in firing off multiple powerful salvos before Oldendorf could reply in kind, and may have been able to outlast Oldendorf in a prolonged gunfight. Due to his mission Kurita may have also had a bombardment-focused ammunition loadout, but precise figures appear unavailable.

Oldendorf’s orders from Admiral Kinkaid directed him to take one division of battleships, one division of heavy cruisers, and about half of his destroyers to assist Taffy 3.25 The remainder of the force would regroup inside Leyte Gulf. To intercept the Center Force Oldendorf formed a special detachment from TF 77.2, and created a force consisting of three battleships, four heavy cruisers, and twenty destroyers. The rest were to proceed to the gulf. By comparison, Kurita had the following warships in the Center Force by this time: four battleships, three heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 13 destroyers.26 Kurita therefore had a meaningful advantage in heavy surface gunnery. His greatest source of advantage in a surface action however came from the Japanese Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo, which possessed double the range of the American Mark 15 torpedo.27 At 30,000 yards of range, the Type 93 had a similar firing distance as extreme-range battleship gunnery.

Oldendorf may have had a useful advantage in geography and the disposition of his forces. The timing of the interception would have likely allowed Oldendorf to engage Kurita’s force in the narrow strait between the Manicani and Homonhon Islands, the final maritime chokepoint Kurita would have had to transit before breaking into Leyte Gulf. Kurita’s westward transit through the strait and Oldendorf’s northward course would have more naturally allowed Oldendorf to configure the disposition of his forces to cross Kurita’s T, and bring the full weight of his firepower to bear. Kurita’s ability to respond would have been constrained by the tight geography of the strait, a six-nautical mile-long chokepoint. If Kurita manages to reconfigure his steaming formation into a battle line within the confines of the strait, a duel between parallel battle lines would have taken Kurita off course from the gulf and cost precious time.

A battle line in such tight quarters would have made for appealing targets for torpedo runs by destroyers, a major liability to both sides. Upon sighting one another, both forces would have likely loosed their light forces against one another to conduct torpedo runs before the surface gunnery would begin. It is here that Kurita would have likely wielded his greatest advantage in the specific context of this hypothetical battle – the Type 93 torpedo. By being able to fire torpedoes well before the Americans can, and by targeting Oldendorf’s battle line blocking the strait, Kurita’s destroyers are likely able to inflict heavy damage against Oldendorf’s heavy surface forces at best, or at least disrupt the battle line formation. Kurita’s advantage in long-range torpedo firepower therefore disrupts Oldendorf’s ostensible advantage in disposition of forces. By setting up a blocking formation at the mouth of the strait, Oldendorf may have actually set himself up to have his own T crossed by devastating torpedo runs.

Oldendorf may have sought a replay of the Battle of Surigao Strait and sent his faster destroyers ahead of the battle line to harass the oncoming Center Force before surface gunnery was joined. Such an action could have scored considerable damage and disrupted the formation of the Center Force. But Oldendorf’s battle line would have likely still been needed to definitively stop Kurita, and it would have been deprived of the cover of darkness that was so useful to Oldendorf’s ambush at Surigao Strait. In facing a substantially stronger force, Oldendorf needed to find ways to maximize his firepower, but forming a battle line formation at the mouth of the strait may have proven a major liability in daytime against major torpedo threats.

The battle line formation is fragile in the confines of a small strait featuring a pervasive torpedo threat. Because of this, Oldendorf’s interception of Kurita would have likely devolved into a gunnery melee. Similar to the multiple surface engagements off Guadalcanal, naval formations would have likely devolved into lone warships, or small groups of warships, firing and maneuvering at will in a bid to win their individual engagements.28 Both sides would have lacked cohesive formations for concentrating firepower and improving command-and-control. It is a challenge to discern net advantage between forces in such a melee, especially given how damage in naval battles can knock out critical ship components that have an outsized influence on a ship’s ability to fight and maintain speed. However, given Kurita’s advantage in heavy surface units and torpedo firepower, the Center Force would have likely prevailed against Oldendorf in such a melee.

How long could Oldendorf have delayed Kurita’s press toward Leyte? With the intercept occurring at roughly 1030, how long would it have taken Kurita’s units to inflict enough damage on Oldendorf’s force to allow for a renewed push toward Leyte? Taken together, the duration of the four major surface gunnery actions near Savo Island suggest that the action between Oldendorf and Kurita would have concluded in roughly two hours, with Kurita’s forces coming out in better shape.29 Therefore Oldendorf probably could have bought the allied forces roughly two hours of time with the destruction of his task force.

At this point it is 1230, and Kurita’s damaged but still effective fighting force is only an hour away from putting the beachhead under its guns. Upon reaching the beachhead at 1330, Kurita then has a relatively open-ended opportunity to expend his ammunition against the beachhead. Based on the rate of fire and ammunition loadout of the main battery of the Center Force’s Yamato battleship, the force would have expended most of its ammunition in a bombardment in roughly two hours of continuous firing.30 Kurita also would have likely opted to retain some ammunition in order to fight his way back out of the gulf and through the San Bernadino Strait. In this alternative scenario, Kurita reaches the beachhead and then completes his bombardment at around 1530.

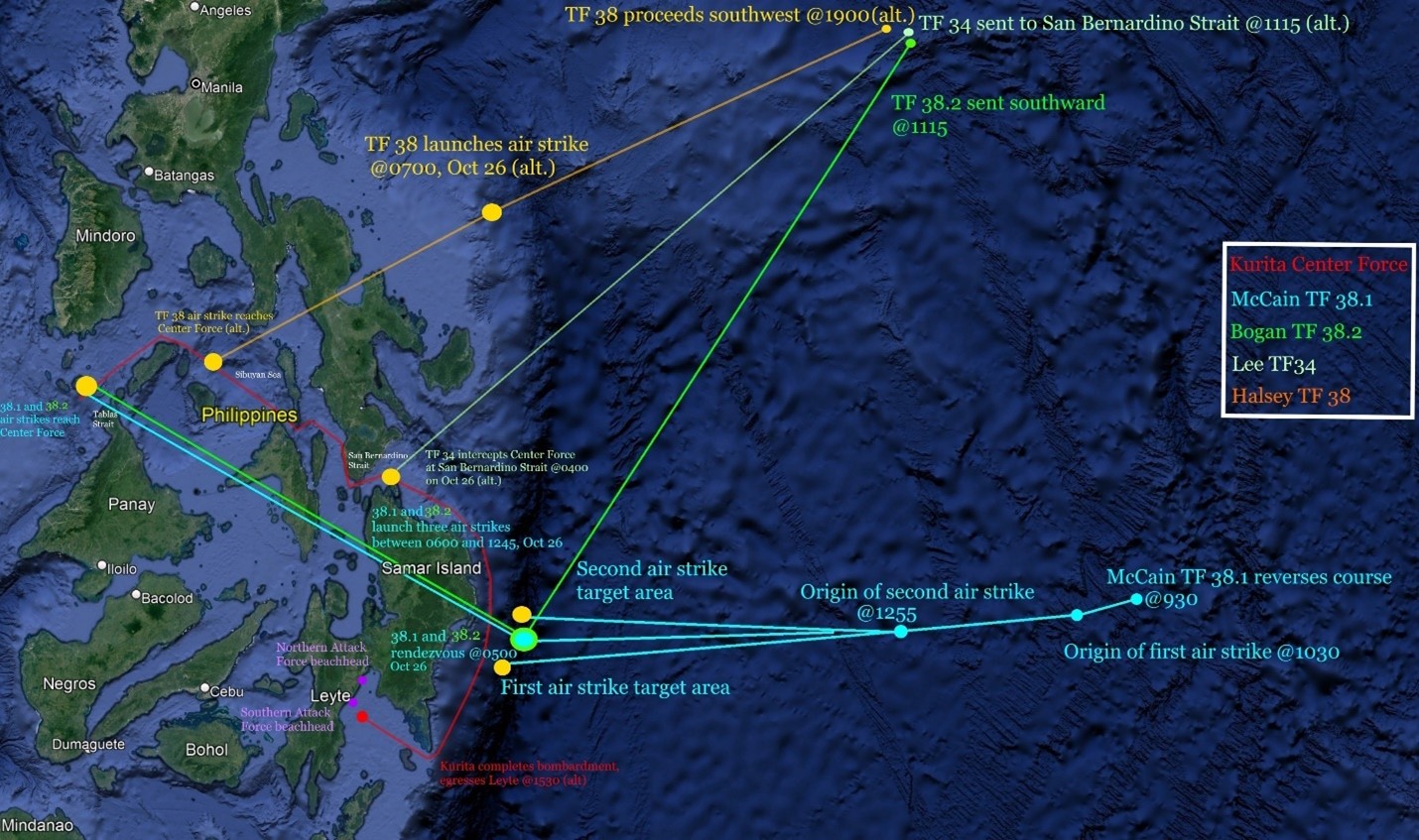

At 1115, halfway through Kurita’s hypothetical battle with Oldendorf, Halsey dispatched TF 34 under Admiral Willis Lee on a course for the gulf. But this force was more than 400 nautical miles away and would have taken about a full day to reach the scene of action. Lee clearly would have been in no position to disrupt the bombardment had it occurred. In this sense, Admiral Halsey was correct in gauging the futility of Admiral Kinkaid’s requests for Lee’s TF 34 to intervene in a surface engagement taking place more than 400 miles away. Kinkaid’s perception that TF 34 was somehow within striking distance of the Battle off Samar is a major symptom of the command confusion that afflicted the discordant 7th and 3rd Fleets.

Multiple New Engagements and Intercepts

If Kurita’s force gets the better of Oldendorf’s force, then there is no heavy surface unit available to disrupt the bombardment of the Leyte beachhead. Therefore the remaining units available to interfere with Kurita’s bombardment and egress are mostly naval air forces. These include the forces comprising the three Taffy units, Taffy 1, 2, and 3, which mainly contained escort carriers and light surface units, as well as the distant forces of Admiral McCain’s fleet carrier task force, TF 38.1.

The airpower of these units stands out for its potential to have long sustained the fight against the Center Force regardless of whether it defeats U.S. surface forces. After being sighted by Taffy 3, Kurita would have likely been under persistent air attack throughout the entirety of his journey to and from the gulf. Given how Kurita was sighted not long after daybreak, he could have been under air attack for almost 11 hours on October 25. These attacks would have included torpedo and bomb threats that could have threatened to unravel the cohesion of the Center Force’s formation and force it onto courses that lengthened its journey toward the gulf. It is critical to ask how much cost, in terms of attrition and time, could have been inflicted by the hundreds of aircraft from these combined carrier forces.

Taffy 1 and 2 were located well away from the Battle off Samar, but were within range of providing some assistance to Taffy 3. These escort carrier forces were not well-equipped for fleet combat actions and were mainly loaded for anti-submarine warfare and shore support to the invasion forces.31 However, they still carried enough bombs and torpedoes to pose a serious threat to heavy surface forces, as evidenced by at least two IJN heavy cruisers that were put out of action within three hours at Samar by escort carrier aircraft.32 An additional heavy cruiser was put out of action by torpedo attacks from Taffy 3’s surface force, substantially cutting down the number of Japanese heavy cruisers Oldendorf would have had to face from six to three.

If Kurita pressed onward past Taffy 3, it would have kept his forces well within striking distance of the three Taffy units. As a combined force, the Taffy order of battle comprised 18 escort carriers, which would have been able to field about 450 aircraft, assuming their air groups were at full strength.33 This was certainly a considerable fighting force, even if its effectiveness was hampered by the limited availability of anti-ship weapons.

An important corollary to Kurita accurately classifying the Taffy 3 contacts as escort carriers is Kurita accurately understanding their mission and what this implied for their aircraft loadouts. By classifying the contacts as escort carriers, Kurita perceives their roles as chiefly being anti-submarine warfare and shore support, rather than fleet-on-fleet combat. While Kurita cannot rule out that the Taffy forces are fielding some measure of heavy anti-ship weaponry, he could ascertain that this is not their main mission and have little in the way of anti-ship ammunition. This understanding allows Kurita to moderate the influence the aerial attacks have on his operational behavior, particularly limiting their ability to pull him off course from the beachhead by compelling evasive maneuvers. Even so, in this alternative it is estimated that evasive maneuvering due to aerial torpedo attack imposes a cost of an additional hour of transit time for Kurita on his way out of the Gulf.

If Kurita had continued his journey southward after being spotted by Taffy 3, he would have been under aerial attack for roughly six hours before entering firing range of the beachhead, inclusive of the two hours his force is held up by Oldendorf. Kurita’s southward journey also brings him within range of the full weight of the Taffy escort carriers, whereas at the historical Battle off Samar, he mainly faced the planes of Taffy 3 and Taffy 2. In response to Taffy 3 coming under fire, all Taffy units were ordered by Kinkaid to recover their aircraft and move northward to assist.34 Had Kurita pressed on to the gulf, it would have been only a matter of time before he was subject to the full weight of the 18 Taffy escort carriers.

However, the longer duration of the alternative sequence of events diminishes the already limited effectiveness of the escort carriers against heavy surface forces. In the historical battle, Taffy 2 had exhausted its limited supply of torpedoes and semi-armor piercing bombs after only four airstrikes against the Center Force, with the fourth strike being launched at 1115.35 The Taffy forces may have had much more opportunity to strike the Center Force in the alternative, but the majority of the time would have likely been spent conducting harassing attacks of limited effect.

Fleet Carrier Forces Intercept Kurita

Fleet carrier forces were of course present at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, but most were fully committed to destroying the carriers of the IJN Northern Force in the Battle off Cape Engaño. The IJN decoy carrier force was successful in pulling Halsey away from the San Bernadino Strait and putting him on a northeast course hundreds of miles away from the gulf. It is therefore unlikely Halsey’s carrier striking forces would have been able to interfere with Kurita’s advance on October 25. Despite the range and speed of carrier aircraft, the distance would have still been too great for Halsey to bring his firepower to bear on Kurita in timely fashion. At the Battle off Cape Engaño, TF 38 launched its final strike against the decoy carrier force at 1615.37 Darkness would have fallen by the time the carriers could have mounted another major strike, ending the possibility of further air attacks that day.

However, by concluding a bombardment at Leyte by roughly 1530, Kurita offers abundant opportunity for Halsey to strike at Kurita the next day. With night falling and the carriers of the IJN Northern Force thoroughly damaged by the evening of October 25, Halsey may have perceived an opportunity to reorient the rest of TF 38 for a major strike against the Center Force. In this alternative, Halsey has wrapped up the Battle off Cape Engaño by 1900 and turns onto a southwestern course. Steaming at a speed of 20 knots for 12 hours, by the next morning Halsey’s TF 38 would have been well within range of launching air strikes across the Sibuyan Sea and over the San Bernardino Strait, where Kurita’s force would have been transiting.38 These alternative timelines create another intersection between forces, precipitating a second Battle of the Sibuyan Sea.

In the actual historical event, fleet carriers did manage to engage Kurita’s Center Force on October 25 off Samar, and again on October 26 in the Sibuyan Sea. On October 22, Admiral John S. McCain Sr.’s TF 38.1 was detached from Halsey’s TF 38 and sent east to replenish at the base of Ulithi.39 Halsey’s first key action in response to Kinkaid’s urgent requests for help was to turn McCain’s task force around at 0930 and set course for the gulf. An hour later McCain’s force, consisting of three fleet carriers and two light carriers, launched an extreme-range air strike in excess of 300 nautical miles, and launched a second and final strike two hours later.40 The extreme range of these strikes forced the planes to forgo heavier ship-killing loadouts, which ultimately resulted in negligible results. But had Kurita remained in Leyte Gulf to complete a bombardment, McCain would have been able to greatly close the distance, equip his planes with heavier payloads, and launch additional strikes on October 25.

When Halsey detached Lee’s TF 34 from TF 38 at 1115, he also detached the fast carrier task force TF 38.2 under Admiral Bogan.41 This latter force rendezvoused with McCain’s TF 38.1 on the morning of October 26 at 0500, and both task forces launched strikes that hit the Center Force in the Tablas Strait west of the Sibuyan Sea.42 These strikes sunk a light cruiser and a destroyer.

The fact these carrier forces were still in range to hit Kurita on October 26 highlights how he may have been subjected to much greater carrier air power in the alternative scenario, where his westward passage through the San Bernadino Strait occurs roughly nine hours later than the historical case. In the alternative, Kurita egresses through the strait on October 26 at roughly 0600, at about the time of sunrise, whereas in the historical case he egressed the strait at 2130 the previous night. This enabled the Center Force to cross most of the Sibuyan Sea under cover of darkness and open the range between Japanese units and American carriers.43 In the alternative, the cost Kurita pays in time to defeat Oldendorf’s force, bombard the beachhead, and egress the gulf substantially expands the opportunity for American carriers to attack the Center Force, especially the following day. On October 26, the second Battle of the Sibuyan Sea would have seen the remnants of the Center Force under aerial attack by a powerful combined force of up to eight fleet carriers and seven light carriers.

Light Surface Forces Intercept Kurita

The Taffy forces also included a considerable amount of light surface units. The three Taffy task forces featured a total of nine destroyers and 11 destroyer escorts, each equipped with torpedoes.44 But only Taffy 3’s surface units engaged the Center Force in the Battle off Samar, with all but one of its seven surface escorts launching torpedo attacks.45 Only one of these torpedo attacks connected with a target, blowing the bow off an IJN heavy cruiser. The primary operational effects of these torpedo attacks were the evasive maneuvers they compelled, which helped break up the Japanese formation and temporarily take it off course from its pursuit.

In the alternative scenario, Kurita’s onward press opens up the opportunity for more Taffy light surface units to attack the Center Force, and to conduct higher quality attacks as well. A cohesive naval formation steaming on a steady course would have made for a much more predictable target for torpedo firing solutions compared to the more disaggregated force that flexibly chased Taffy 3. The light surface units from Taffy 1 and Taffy 2 would have had more than enough time to reach the Center Force and contribute their own attacks.

It is difficult to imagine that Kurita would be able to steadfastly hold his course toward the beachhead while under torpedo attack. At a minimum, these attacks would have inflicted a cost in time due to the evasive maneuvering they compelled. It is also likely that Kurita would have incurred a cost in cohesion by detaching his light forces so they may close with the U.S. light surface units and spoil their torpedo runs. Light forces feature high speed and maneuverability, making them challenging targets for heavy caliber weapons to strike at range. Kurita would have likely depended on his destroyers to disrupt the attacks of the opposing light forces, in order to keep his heavy units on a steadier course toward his ultimate objective. In the alternative, it is estimated that evasive maneuvering spurred by surface unit torpedo attacks imposes an additional hour of transit time on Kurita’s egress.

It is possible that not all 20 of the Taffy surface units would have contributed to an attack on the Center Force, even if there was an abundance of time and opportunity. These units were mainly meant to screen their respective escort carriers. Screening roles and dispositions do not typically offer light surface units the proximity and independence needed to launch torpedo runs. In the historical event, Taffy 2’s surface units were well within range of reaching the point of contact and launching torpedo attacks, but the Taffy 2 commander opted to keep these forces in their screening roles.46 In the alternative, it is likely that more but not all of the Taffy surface units would have been detached to perform torpedo runs against the Center Force.

Heavy Forces Intercept Kurita

The extra nine-hour cost in time that Kurita incurs in a press to the beachhead and back creates a critical opportunity for the U.S. to intercept the Center Force with fresh heavy surface forces. If Lee’s TF 34 were to proceed straight to San Bernadino Strait after being detached from TF 38 at 1115, it would have been at the strait roughly two hours before Kurita, at around 0400. This would have allowed Lee to effectively set the disposition of his force to block the strait and maximize his available firepower in the direction of Kurita’s advance. Lee’s force would have had a major advantage in both numbers of heavy surface units (six battleships) and ammunition compared to Kurita’s force, which would have been heavily depleted and battered by air and torpedo attacks by this time.

Lee’s superiority would have been overwhelming. Had Lee been able to lock Kurita into a decisive engagement on these terms, TF 34 would have likely completed the destruction of the Center Force. However, the relatively close timing of this early morning intercept means that Kurita may have had some opportunity to slip through the strait before Lee could have engaged. The more time that Oldendorf and allied torpedo attacks impose on Kurita’s timetable, the greater Lee’s chances of intercepting and decisively destroying the Center Force at the strait.

The timing and location of Kurita’s early morning strait transit at 0600 also suggests that the full weight of the combined forces of TF 38 and TF 34, featuring numerous fleet carriers and battleships, could have been brought to bear against the Center Force in these early daylight hours. What the alternative reveals is that U.S. forces are able to impose multiple new engagements on the Center Force given the intersecting timelines created by Kurita’s longer journey to and from Leyte Gulf.

Bombardment, Attrition, and Strategic Effect

Had he pushed through, Kurita would have likely enjoyed a lengthy opportunity to bombard the Leyte beachhead, even if he would have been under persistent air attack. Kurita’s gunnery may have been spoiled at times by evasive maneuvering spurred by torpedoes, but the U.S. forces that could have threatened Kurita in the 1030-1530 timeframe are unlikely to pose an overwhelming threat. Kurita would have had enough operational freedom to expend the bulk of his firepower against the beachhead before retiring. However, the cost in time Kurita incurs in pressing toward the gulf substantially expands the opportunity for the U.S. to strike the Center Force, which would have likely been destroyed during its egress.

The added attrition Kurita could have inflicted and suffered is ultimately of limited strategic effect. Kurita’s ability to influence the course of events in the Pacific War at Leyte was eclipsed by a combination of American industrial might and a new dominant mode of warfare that had already rendered the Center Force of limited value. A heavy bombardment of the Leyte beachhead and its transports could have hampered U.S. operations for a matter of weeks at most, but could not have been decisive enough to achieve its intended objective – the foreclosure of the invasion.

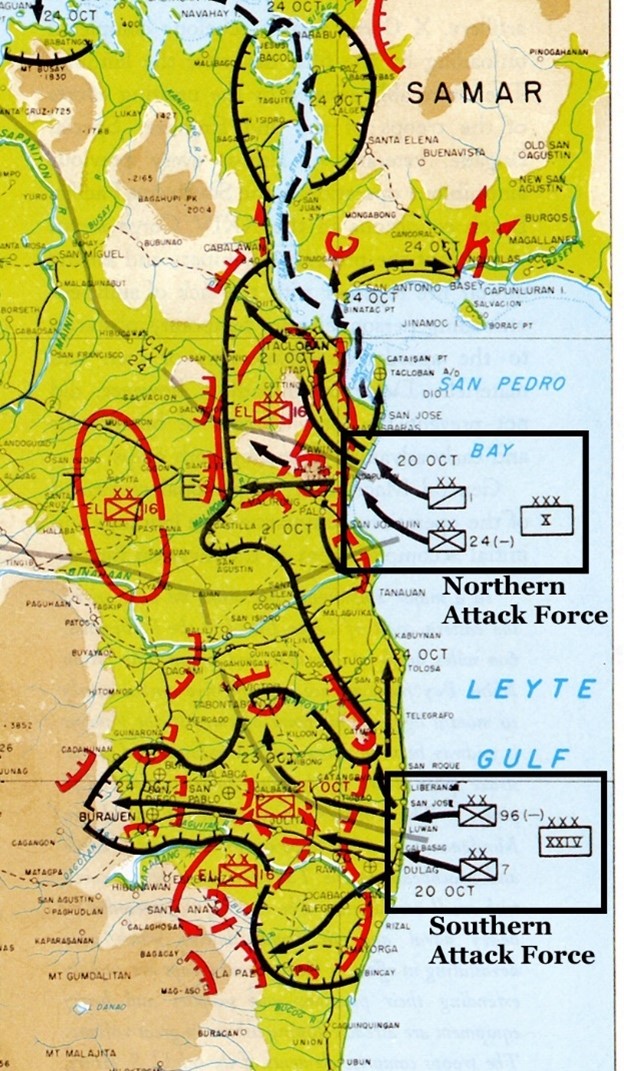

The allied invasion of Leyte was divided into two main landing sites, with the Northern Attack Force landing south of the city of Tacloban, and the Southern Attack Force landing near Dulag, with the landing sites being separated by about 12 nautical miles.47 Five days after the October 20 invasion of Leyte, allied forces had delivered 81,000 troops and 115,000 tons of supplies ashore for the Northern Attack Force, and 50,000 troops and 85,000 tons ashore for the Southern Attack Force.48 While the invading forces had made it well inland by the time Kurita could have entered the gulf, their logistical infrastructure was still heavily concentrated on the shore areas.

According to Admiral Koyanagi, Kurita’s chief of staff at the battle, the Combined Fleet Headquarters directed that Kurita’s primary target be the invasion’s amphibious transport ships.50 This was a reference to the large Landing Ship, Tank (LST) vessels, which were crucial to the allied war effort. LSTs were needed for carrying armored vehicles and large amounts of logistical needs for allied forces. Their amphibious capability allowed them to deliver their cargoes over shorelines, rather than only be limited to port infrastructure like conventional cargo vessels.

These ships were so critical that their limited availability had a constraining influence on allied strategy, especially with multiple allied invasions occurring on opposite sides of the globe. The D-Day invasion was postponed by a month partly in order to have enough LSTs deemed sufficient for sustaining the invasion.51 As General Eisenhower wrote to General Marshall, “we will have no repeat no LSTs reaching the beaches after the morning of D plus 1 until the morning of D plus 4.” After the decision to postpone was made, Eisenhower wrote Marshall again to say “one extra month of landing craft production, including LSTs, should help a lot.”52 The Battle of Leyte Gulf occurred only four months after the D-Day invasion, which had absorbed a substantial amount of allied LST capacity, suggesting that these vessels were still in especially high demand.

According to Samuel Eliot Morison, on October 24-25 there remained 23 LSTs and 28 Liberty ships in Leyte Gulf.53 It is unclear how many of these vessels were afloat or beached, but perhaps they may have been able to escape the gulf if given a few hours’ notice of Kurita’s advance. The ability to reposition shoreside supply dumps may have been more limited. It is plausible that if Kurita had penetrated into the gulf, his large and powerful force would have had more than enough ammunition and opportunity to sink most if not all of the transports if they were unable to escape beforehand.

The amount of destruction Kurita could have wrecked on the transport vessels amounts to about a month’s worth of LST construction and two weeks’ worth of Liberty ship construction.54 More than 120 LSTs participated in unloading the invasion forces between October 20-25, suggesting Kurita could have knocked out about 20 percent of the LSTs in the vicinity. The D-Day experience is instructive, namely that the originally planned for May 1, 1944 invasion called for 230 LSTs, but only a month’s worth of LST production was deemed necessary enough to compel a delay to June.55 While the broader availability of LSTs is unclear in the October 1944 timeframe, it is noteworthy that even at the peak of American wartime industrial output, the limited availability of the LST had a constraining effect on strategy. It can be expected that the destruction of LSTs and other transports in the Leyte Gulf would have had a noteworthy effect on the Philippine campaign, including a temporarily diminished operational tempo and possibly even a shift to a defensive posture until logistical capacity could be regenerated.

Regeneration may have taken several weeks and occurred in the midst of the Japanese counterattacks on Leyte. The Japanese military had more than 430,000 troops on the Philippines, but only 20,000 on Leyte at the time of invasion.56 U.S. airpower was highly successful at interdicting Japanese ship transports aiming to reinforce Leyte after the invasion, to where two months later in December the Japanese were only able to reinforce their presence on Leyte to 34,000 troops.57 The Japanese were having their own transports harassed and destroyed, contributing to their inability to push the invasion force of more than 130,000 troops back into the sea. It is therefore doubtful that losing whatever transports were present in the gulf on October 25 would have been decisive enough to foment a collapse of the U.S. lodgment, much less decisively foreclose the option of a Philippine invasion.

In terms of Japanese attrition, Kurita took substantial losses at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and would have suffered even more in the alternative. Kurita began the battle with five battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 15 destroyers. He ended the battle with four battleships, two heavy cruisers, and 13 destroyers.58 In the alternative, he is most likely destroyed wholesale, due to the overwhelming amount of firepower he invites with a lengthier operation.

Many forces that could not engage Kurita in the historical case would have had an opportunity to do so in the alternative. In the alternative scenario, the following additional forces gain an opportunity to impose new engagements on Kurita: Oldendorf’s detachment from TF 77.2 (three battleships, four heavy cruisers, 20 destroyers); Lee’s TF 34 (six battleships, three light cruisers, eight destroyers); Admiral T.L. Sprague’s Taffy 1 (six escort carriers); Taffy 1 and Taffy 2 light surface forces (up to six destroyers and seven destroyer escorts); and the remainder of Halsey’s TF 38 carrier forces (four fleet carriers and three light carriers). Kurita would have also faced additional air attacks from McCain’s TF 38.1 (three fleet carriers, two light carriers) and Bogan’s TF 38.2 (one fleet carrier, two light carriers).59 By pressing toward the beachhead, Kurita dramatically expands the striking opportunity U.S. forces would have had against the Center Force due to an estimated increase in operational duration of only nine hours. Against such overwhelming odds, it is likely that Kurita’s Center Force would have been decisively destroyed, or a few heavily damaged units would have survived at best.

The strategic impact of a steeper sacrifice from Kurita would have been marginal. The historical case of the Battle of Leyte Gulf is already widely regarded as the battle that decisively ended the Imperial Japanese Navy as a fighting force of strategic value.60 This stems not from the extensive losses the Japanese heavy surface forces took, but from the conclusive destruction of the bulk of the IJN’s remaining carrier forces at the Battle off Cape Engaño, where one fleet carrier and three light carriers were sunk.61 These carriers could only serve as decoys because their air wings had not recovered from the heavy attrition they suffered at the Battle of the Philippine Sea four months earlier. But this was unknown to the Americans, causing Halsey to justifiably concentrate his fleet’s striking power against the opposing carrier force. As Halsey later wrote of his decision during the battle,

“In modern naval warfare there is no greater threat than that offered by an enemy carrier force. To leave such a force untouched and to attack it with anything less than overwhelming destructive force would not only violate this proven principle but in this instance would have been foolhardy in the extreme.”62

This complements a rationale offered by Kurita’s chief of staff, Admiral Koyanagi, who argued:

“In modern sea warfare, the main striking force should be a carrier group, with other warships as auxiliaries. Only when the carrier force has collapsed, should the surface ships become the main striking force. However majestic a fleet may look, without a carrier force it is no more than a fleet of tin.”63

In the case of Halsey, he aggressively pursued decoy carriers, in the case of Kurita, he aggressively pursued falsely classified escort carriers. Both sides were understandably seduced by the strategic opportunity of inflicting heavy damage against carrier forces. They shared a common recognition that carrier strike had emerged as the dominant mode of blue water naval warfare in WWII, and to destroy the handful of capital ships at the core of this new paradigm would have opened up outsized strategic possibilities.

By comparison, a navy deprived of carriers would have few good options for contesting sea control, options that increasingly depend on significant amounts of luck and skill. These options include sending submarines through dense and overlapping layers of screening forces, having surface forces seek out decisive night engagements, or sending surface units through a gauntlet of hundreds of miles of carrier strike before they can finally bring their guns to bear. Such was the fate of the super battleship Yamato that sailed with Kurita, which was later sacrificed in a suicide run against the Okinawa invasion force.64

The dominant mode of warfare is why the destruction of IJN carrier forces at the Battle of Cape Engaño is what ultimately allowed the U.S. to operate without much concern for the Imperial Japanese Navy for the remainder of the Pacific war. If Kurita’s Center Force had never set sail for Leyte, the effect would have been much the same.

Historical Probability

The probability of this alternative appears quite high. The historical case featured Kurita choosing a major deviation from his standing orders and narrowly escaping the firepower of multiple converging naval formations. Had Kurita adhered to his original intent, he would have been more likely to reach the beachhead than not, and more likely than not to have his force destroyed. It is estimated here that some version of this alternative was actually the more likely event, with the historical reality being the less likely outcome.

The key factor is Kurita accurately classifying the flattops of Taffy 3 as escort carriers. An accurate classification could have been enabled by various means and factors. The Yamato battleship carried multiple reconnaissance float planes that could have been launched to provide some measure of improved awareness, even if they would not survive for long with U.S. carrier air attacking the Center Force. The Japanese battleship force had also suffered relatively little attrition up until this point in the war and was not seriously deprived of experienced personnel like the depleted naval aviation arm.

Kurita could have also properly classified the escort carriers and their escorts after being under attack by them for several hours. The volume of Taffy 3 aircraft and the intensity of their attacks hardly compared to the powerful beating the Center Force took from five fleet carriers in the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea the day prior. The Center Force also received no heavy gunnery salvos in response to its pursuit, which should have highlighted the major improbability of a force of multiple fleet carriers somehow having no escorts larger than a destroyer.

The ability to accurately identify Taffy 3’s flattops as escort carriers was certainly complicated by its effective tactics of conducting a fighting withdrawal, including extensive use of smokescreens, maneuvering into local squalls, and torpedo attacks that forced Kurita’s pursuing forces to temporarily break contact for the sake of evasion.65 But even so, the combination of factors, especially experience, should have made an accurate classification more likely than not.

Each of the hypothetical intercepts also become highly probable in the alternative if Kurita presses on. Oldendorf’s intercept is practically guaranteed by virtue of proximity and the likely duration of Kurita’s presence in the gulf. The Taffy forces and McCain’s TF 38.1 are also virtually guaranteed to have more opportunity to launch more airstrikes than the historical case. Lee’s ability to intercept an egressing Kurita at San Bernardino Strait is more likely to happen than not, given the extensive cost in time that Kurita pays for his drive to the gulf. Because of the same time costs, Halsey’s TF 38 is well within range of striking Kurita in the Sibuyan Sea the next day, and the combined forces of McCain’s TF 38.1 and Bogan’s TF 38.2 also have much more opportunity to strike. Every hour it costs Kurita to press deeper in the gulf converts into more daylight striking opportunity the following day by multiple converging carrier forces.

The possibility of these alternative engagements fundamentally hinges on a relatively small increase in operational duration. Within an hour of Kurita being sighted by Taffy 3, American naval commanders set in motion a series of counter-moves that would close in on Kurita in a matter of hours. Had Kurita held to his orders and had he accurately classified the escort carriers, these alternative clashes would have been more likely to happen than not.

Counterarguments

Kurita was pulled into an engagement with the Taffy escort carriers because he saw a decisive opportunity, a perception that was encouraged by the dominant mode of naval warfare and the IJN’s institutional doctrine of prioritizing decisive fleet engagements. The main counterargument to the alternative is that the opportunity of striking fleet carriers fits neatly enough with the preferences of Kurita and IJN doctrine, making the historical case the more likely outcome.

While Kurita’s primary objective was the Leyte beachhead, the naval staff of the Center Force and the staff of the Combined Fleet Headquarters had previously discussed the possibility of a fleet engagement. It was generally agreed upon that a crippling blow to the enemy’s carrier force would have had a far more strategic effect on the war than heavily damaging the beachhead. Kurita’s chief of staff, Admiral Koyanagi, expressed this thinking:

“Our one big goal was to strike the United States fleet and destroy it. Kurita’s staff felt that the primary objective of our force should be the annihilation of the enemy carrier force and that the destruction of enemy convoys should be but a side issue. Even though all enemy convoys in the theater should be destroyed, if the powerful enemy carrier striking force was left intact, other landings would be attempted, and in the long run our bloodshed would achieve only a delay in the enemy’s advance. On the other hand, a severe blow at the enemy carriers would cut off their advance toward Tokyo and might be a turning point in the war. If the Kurita Force was to be expended, it should be for enemy carriers…Kurita and his staff had intended to take the enemy task force as the primary objective if a choice of targets developed.”66

Yet Koyanagi also explained that the tension between these objectives was affecting the force’s leadership. Kurita’s Center Force knew it would deploy deep in the battlespace with little naval air cover and potentially face devastating American carrier strikes, which it eventually did in the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea. It would require steadfast determination to subject one’s force to this punishment while in pursuit of an objective that was not the enemy’s main battle fleet, especially if that battle fleet happened to come within range of heavy surface gunnery. With respect to the Combined Fleet’s operational policy of prioritizing the beachhead, Koyanagi described the attitude of the Center Force staff: “our whole force was uneasy, and this feeling was reflected in our leadership during the battle.”

Taffy 3 therefore provided an opportunity for the Center Force to focus on its preferred operational aim – a fleet-on-fleet engagement. Encountering Taffy 3 allowed Kurita to redirect his focus given how a “choice in targets” had in fact developed. The previous day’s heavy punishment in the Sibuyan Sea likely reinforced the desire to destroy carriers. Kurita pursued Taffy 3 at top speed for nearly three hours, possibly thinking he had come upon one of the luckiest breaks for the Imperial Japanese Navy in the war. As Koyanagi described the initial sighting of Taffy 3,

“This was indeed a miracle. Think of a surface fleet coming up on an enemy carrier group! We moved to take advantage of this heaven-sent opportunity. Yamato increased speed instantly and opened fire at a range of 31 kilometers. The enemy was estimated to be four or five fast carriers guarded by one or two battleships and at least ten heavy cruisers.”67

In fact, Taffy 3 contained six escort carriers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts. Taking Koyanagi’s upper figures, the Center Force overestimated the tonnage of the naval force it encountered by a factor of five.68

While the Center Force’s strong preference for engaging in fleet battles was understandable, the multiple factors that should have enabled accurate classification remain plausible. They also become more plausible as time goes on during the Battle off Samar, given how the attacks of Taffy 3 and its escorts increasingly reveal their marginal capability compared to the major fleet combatants the Center Force misclassified them as. The institutional preference for fleet engagement is the strongest factor buttressing the historical case, but it is still weaker than the combination of multiple factors that make the alternative more likely.

Conclusion

The Battle of Leyte Gulf was an intricate engagement, consisting of multiple separate but interconnected battles. If any of these battles resulted in different outcomes, it would have affected the operational behavior of the forces in the other clashes. By slipping through the San Bernadino Strait, the Center Force exerted a powerful influence over the behavior of all major U.S. naval forces present at the battle, including many that never got a chance to engage Kurita. But had Kurita not been diverted by the escort carriers of Taffy 3, he would have likely earned an opportunity to bombard his primary objective, while also creating an opportunity for his force’s annihilation.

Kurita’s efforts were ultimately futile regardless of his courses of action. By then the industrial might of the U.S. was conferring overwhelming material superiority to the allies, as exemplified by the more than 15 fleet carriers and 120 escort carriers that were produced during the war years.69 That Kurita sortied at all is more a testament to the obstinate fatalism of the Japanese Empire rather than its strategic acumen.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf remains the most recent high-end, fleet-on-fleet combat action despite occurring 80 years ago. It endures as a highly instructive case of naval warfare, whose many fundamentals can still apply today. Whether it is command confusion afflicting U.S. operations, on-scene leaders perceiving what they want to see in enemy forces, or fast-breaking decisions defining combat outcomes, modern warfighters should recognize that future fleet battles may be rife with similar challenges. If U.S. naval forces are ever sortied against daring odds to damage a beachhead on a foreign shore, they should heed Koyanagi’s warning – “As in all things, so in the field of battle, none can tell when or where the breaks will come.”

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. He is the author of the Fighting DMO and How the Fleet Forgot to Fight series. He is coauthor of Learning to Win: Using Operational Innovation to Regain the Advantage at Sea against China. Contact him at [email protected].

References

[1] Martin R. Waldman, “CALMNESS, COURAGE, AND EFFICIENCY,” Remembering the Battle of Leyte Gulf, pg. 3-4 (PDF pg. 7-8), Naval History and Heritage Command, 2019, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/publications/publication-508-pdf/battle_leyte_gulf_508.pdf.

[2] Samuel E. Morison, “History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945,” pg. 184-187, 1958, Little, Brown and Company, https://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00mori/page/n3/mode/2up.

[3] Ibid, pg. 189.

[4] Ibid, pg. 190.

[5] Rear Admiral Tomiji Koyanagi, former Imperial Japanese Navy, “With Kurita at Leyte Gulf,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, February 1953, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1953/february/kurita-battle-leyte-gulf.

[6] Interrogations of Japanese Officials – Vols. I & II United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific), https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/interrogations-japanese-officials-voli.html#no35.

[7] Samuel E. Morison, “The Battle of Surigao Strait,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, December 1958, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1958/december/battle-surigao-strait.

[8] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 14 (PDF pg. 9), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[9] Admiral W.A. Lee, Jr., “Report Of Operations Of Task Force Thirty-Four During The Period 6 October 1944 To 3 November 1944,” December 14, 1944, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/rep/Leyte/TF-34-Leyte.html.

[10] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 67 (PDF pg. 37), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[11] Image “Plate NO. 60,” from, Reports Of General MacArthur: The Campaigns Of MacArthur In The Pacific, Volume I, pg. 210 (PDF pg. 229), https://history.army.mil/html/books/013/13-3/CMH_Pub_13-3.pdf.

[12] Richard Bates, The Battle for Leyte Gulf. October 1944. Strategical and Tactical Analysis. Volume V. Battle of Surigao Strait, October 24th-25th, pg. 656-657 (PDF pg. 799-800), U.S. Naval War College, 1958, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/rep/Leyte/NWC-5.pdf.

[13] Ibid, pg. 664 (PDF pg. 807).

[14] Ibid, pg. 675, (PDF pg. 818).

[15] Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired), “The Battle for Leyte Gulf,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 1952, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1952/may/battle-leyte-gulf.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Admiral W.A. Lee, Jr., “Report Of Operations Of Task Force Thirty-Four During The Period 6 October 1944 To 3 November 1944,” December 14, 1944, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/rep/Leyte/TF-34-Leyte.html.

[20] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 78 (PDF pg. 43), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[21] For Kurita, see: Interrogations of Japanese Officials – Vols. I & II United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific), https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/interrogations-japanese-officials-voli.html#no35.

For Lee, see: Admiral W.A. Lee, Jr., “Report Of Operations Of Task Force Thirty-Four During The Period 6 October 1944 To 3 November 1944,” December 14, 1944, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/rep/Leyte/TF-34-Leyte.html.

[22] Samuel E. Morison, “The Battle of Surigao Strait,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, December 1958, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1958/december/battle-surigao-strait.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Samuel E. Morison, “History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945,” pg. 295, 1958, Little, Brown and Company, https://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00mori/page/n3/mode/2up.

[25] Richard Bates, The Battle for Leyte Gulf. October 1944. Strategical and Tactical Analysis. Volume V. Battle of Surigao Strait, October 24th-25th, pg. 675 (PDF pg. 818), U.S. Naval War College, 1958, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/rep/Leyte/NWC-5.pdf.

[26] Eugene Cammeron, “Battle off Samar,” Navweps, http://www.navweaps.com/index_oob/OOB_WWII_Pacific/OOB_WWII_Samar.php.

[27] Norman Friedman, “A Massive Torpedo,” Naval History Magazine, April 2019, https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2019/april/massive-torpedo.

See also: Samuel J. Cox, “H-008-3: Torpedo Versus Torpedo,” Naval History and Heritage Command, July 2017, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-008/h-008-3.html.

[28] For narratives and analysis of the naval battles off Guadalcanal, see Trent Hone, Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945, Naval Institute Press, 2019, and Jim Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal, Bantam, 2012.

[29] Ibid.

[30] For rate of fire, see: Captain C.G. Grimes, Target Report – Japanese 18″ Guns and Mounts, pg. 50 (PDF pg. 53), Chief Naval Technical Mission to Japan, February 1946, https://web.archive.org/web/20141022175714/http:/www.fischer-tropsch.org/primary_documents/gvt_reports/USNAVY/USNTMJ%20Reports/USNTMJ-200F-0384-0445%20Report%20O-45%20N.pdf.

For ammunition capacity of Yamato, see: Samuel J. Cox, “H-044-3: “Operation Heaven Number One” (Ten-ichi-go)—the Death of Yamato, 7 April 1945,” April 2020 2020, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-044/h-044-3.html.

[31] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 98 (PDF pg. 54), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[32] Ibid, pg. 78 (PDF pg. 43).

[33] Ibid, pg. 112-113, (PDF pg. 61).

[34] Ibid, pg. 69 (PDF pg. 38).

[35] Ibid, pg. 98 (PDF pg. 54).

[36] Image “Plate NO. 62,” from, Reports Of General MacArthur: The Campaigns Of MacArthur In The Pacific, Volume I, pg. 219 (PDF pg. 238), https://history.army.mil/html/books/013/13-3/CMH_Pub_13-3.pdf.

[37] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 89 (PDF pg. 49), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[38] The effective combat radius of U.S. WWII fleet carriers was about 300 miles. For effective range of U.S. WWII fleet carriers, see: Dr. Jerry Hendrix, Retreat from Range: The Rise and Fall of Carrier Aviation, pg. 17-19, Center for a New American Security, October 2015, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/194448/CNASReport-CarrierAirWing-151016.pdf.

Also see Samuel E. Morison’s description of McCain’s initial air strike against the Center Force, which at 335 miles Morison described as “one of the longest carrier strikes of the war. Samuel E. Morison, “History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945,” pg. 309, 1958, Little, Brown and Company, https://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00mori/page/n3/mode/2up.

[39] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 23 (PDF pg. 13), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[40] Samuel E. Morison, “History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945,” pg. 309, 1958, Little, Brown and Company, https://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00mori/page/n3/mode/2up.

[41] Admiral W.A. Lee, Jr., “Report Of Operations Of Task Force Thirty-Four During The Period 6 October 1944 To 3 November 1944,” December 14, 1944, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/rep/Leyte/TF-34-Leyte.html.

[42] Samuel E. Morison, “History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945,” pg. 311, 1958, Little, Brown and Company, https://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00mori/page/n3/mode/2up.

[43] Ibid, pg. 310.

[44] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 112-113 (PDF pg. 61), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[45] Ibid, pg. 72-73 (PDF pg. 40).

[46] Ibid, pg. 76-77 (PDF pg. 42).

[47] Samuel E. Morison, “History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945,” pg. 135, 1958, Little, Brown and Company, https://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00mori/page/n3/mode/2up.

[48] Ibid, pg. 155-156.

[49] Image “Plate NO. 58,” from, Reports Of General MacArthur: The Campaigns Of MacArthur In The Pacific, Volume I, pg. 201 (PDF pg. 220), https://history.army.mil/html/books/013/13-3/CMH_Pub_13-3.pdf.

[50] Rear Admiral Tomiji Koyanagi, former Imperial Japanese Navy, “With Kurita at Leyte Gulf,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, February 1953, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1953/february/kurita-battle-leyte-gulf.

[51] Craig L. Symonds, “The unloved, unlovely, yet indispensable LST,” Navy Times/WWII Magazine, June 6, 2019, https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/06/06/the-unloved-unlovely-yet-indispensable-lst/.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Samuel E. Morison, “History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 12, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945,” pg. 156, 1958, Little, Brown and Company, https://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00mori/page/n3/mode/2up.

[54] For LST construction rate, see: Craig L. Symonds, “The unloved, unlovely, yet indispensable LST,” Navy Times/WWII Magazine, June 6, 2019, https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/06/06/the-unloved-unlovely-yet-indispensable-lst/.

For Liberty ship construction rate, see: Gus Bourneuf Jr., Workhorse of the Fleet: A History of the Liberty Ships, pg. 112 (PDF pg. 120), American Bureau of Shipping, 1990, https://ww2.eagle.org/content/dam/eagle/publications/company-information/workhorse-of-the-fleet-2019.pdf.

[55] Craig L. Symonds, “The unloved, unlovely, yet indispensable LST,” Navy Times/WWII Magazine, June 6, 2019, https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/06/06/the-unloved-unlovely-yet-indispensable-lst/.

[56] Charles R. Anderson, Leyte: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II, pg. 14, Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 2019, https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-27/CMH_Pub_72-27(75th-Anniversary).pdf.

[57] Ibid, pg. 24.

[58] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 105 (PDF pg. 57), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[59] The carrier Princeton is not counted given how it was sunk several days before the battle. For overall order of battle, see: Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 107-113 (PDF pg. 58-61), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[60] John Grady, “Panel: Lessons Learned from the Battle of Leyte Gulf Endure,” USNI News, October 26, 2019, https://news.usni.org/2019/10/26/panel-lessons-learned-from-the-battle-of-leyte-gulf-endure.

[61] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 87-90 (PDF pg. 48-50), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[62] Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired), “The Battle for Leyte Gulf,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 1952, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1952/may/battle-leyte-gulf.

[63] Rear Admiral Tomiji Koyanagi, former Imperial Japanese Navy, “With Kurita at Leyte Gulf,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, February 1953, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1953/february/kurita-battle-leyte-gulf.

[64] Samuel J. Cox, “H-044-3: “Operation Heaven Number One” (Ten-ichi-go)—the Death of Yamato, 7 April 1945,” April 2020 2020, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-044/h-044-3.html.

[65] Battle Summary No. 40, The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23rd-26 October, 1944, pg. 70-72 (PDF pg. 39-40), Tactical and Staff Duties Division, Historical Section, Royal Australian Navy, May 1947, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Battle_Summary_No_40.pdf.

[66] Rear Admiral Tomiji Koyanagi, former Imperial Japanese Navy, “With Kurita at Leyte Gulf,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, February 1953, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1953/february/kurita-battle-leyte-gulf.

[67] Ibid.

[68] This calculation is based on the tonnage of following common classes of American WWII warship: Essex-class fleet carriers, Casablanca-class escort carriers, Baltimore-class heavy cruisers, and Fletcher-class destroyers.

[69] For fleet carrier production, see: Scot MacDonald, “The Evolution of Aircraft Carriers: The Early Attack Carriers,” pg. 47 (PDF pg. 49) Naval Aviation News, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-D221-PURL-gpo67727/pdf/GOVPUB-D221-PURL-gpo67727.pdf.

For escort carrier production, see: Ensign G. I. “Ike” Heinemann, U.S. Navy, “Bring Back the CVLs,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, June 2019, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2019/june/bring-back-cvls.

Featured Image: 24 October 1944 – The Japanese battleship Yamato is hit by a bomb near her forward 460mm gun turret, during attacks by U.S. carrier planes during the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea. (U.S. Navy photo)