Notes to the New Administration Week

By David Ware

As a retired U.S. Customs Service and U.S. Customs and Border Protection Supervisor in Hawaii, I have done warrantless border searches of yachts and fishing vessels as well as large commercial vessels. We apprehended many violators with arrest warrants from all over the United States. Seizures of weapons, including an AK-47, were made. Illegal drugs were often encountered. Illegal immigrants were taken into custody.

Intelligence and enforcement must go hand-in-hand. Many of these small boats simply pop over the horizon without notice or warning. Customs, Coast Guard, and the state of Hawaii cooperated to ensure a seamless approach. That was 30 years ago. In 2003, everything changed with the creation of the new Department of Homeland Security (DHS). In the aftermath of 9/11, Customs and Immigration inspections were combined into CBP, and their respective investigations were combined into Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)/Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). This was a mistake because Customs’ role in border security was subjugated to strictly admissibility and immigration issues. We became part of DHS, a government entity still trying to define its mission today in 2025.

The United States has an enormous coastline, including the Pacific, the Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, and also the Great Lakes which we share with Canada. For political reasons, enforcement across the Great Lakes, including at the Port of Buffalo, NY, was curtailed several decades ago. But after 9/11, Customs reinforced the northern border before the southern border because it was considered more of a threat for terrorist penetration. There was also intelligence after the 9/11 attacks that suggested Al-Qaeda would put a weapon of mass destruction in a cargo container on a vessel, possibly coming across the Pacific from China or Japan, potentially into or via Hawaii.

What is concerning today is that the DHS intelligence and enforcement posture for national security purposes, for both large and small vessels, appears to have taken a backseat to focus strictly on immigration concerns. This creates a maritime security opening for adversaries to exploit.

Maritime security extends far beyond the continental United States. While illegal vessels come up from Mexico and Latin America on both the east and west coasts, the Chinese Coast Guard and Maritime Militia seek to dominate and control the high seas in strategic waters near U.S. allies and territories. It is not just PLA Navy warships that threaten America, it is China’s comprehensive maritime power and gray zone strategy, which includes a substantial coast guard and paramilitary element for which we have no commensurate response. Consider Chinese vessels approaching the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands without a visa, or illegally entering Guam on boats. Both are U.S. territories of strategic value. Chinese coast guard vessels and maritime militia are also on the frontlines of encroaching upon U.S. partners and allies in day-to-day operations, and could serve many wartime roles as well.

The new administration should focus on maritime security, both at home and abroad, because it has long been neglected. The number one threat to maritime security is China. Unguarded seacoasts are America’s greatest vulnerability.

David Ware is a retired federal officer with 42 years of combined military and civilian federal service. He served in the U.S. Air Force, with service in the Philippines and Okinawa during the Vietnam War era. He has extensive experience dealing directly with Pacific nations and territories in Project Cook and the Customs Asia-Pacific Enforcement Reporting System (CAPERS). He is a retired U.S. Customs and Border Protection supervisor and analyst.

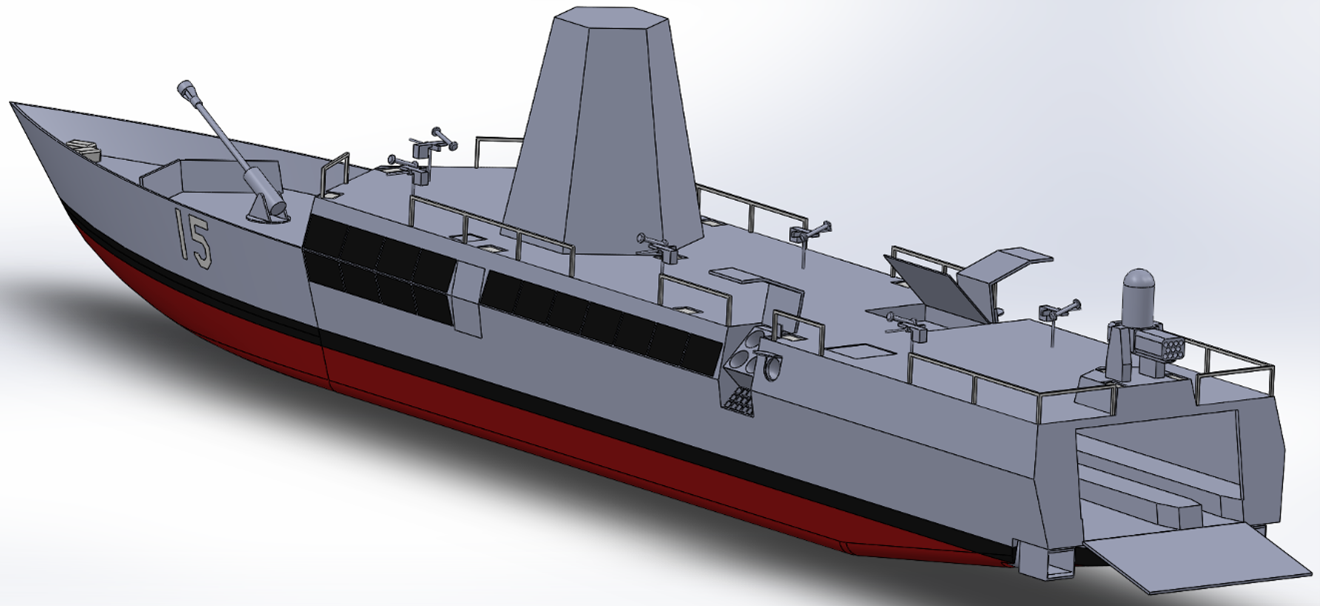

Featured Image: A Coast Guard Cutter Diligence pursuit team interdicts a “go-fast” boat suspected of smuggling illegal drugs (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Cutter Diligence/Released)