By Dr. Rob Gates

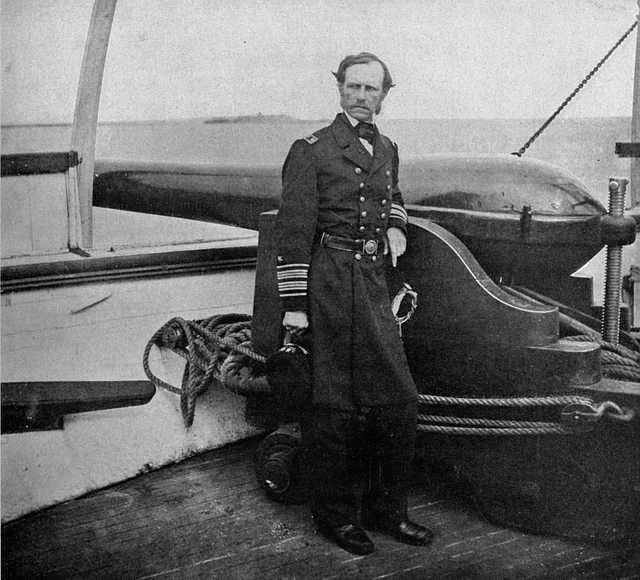

When I give a tour of the Dahlgren Heritage Museum, I always start at the photograph of Admiral John A. Dahlgren. It’s not unusual to get questions like “Was he born around here?” or “When was he stationed here?” The answers to those questions are, respectively, “No” and “Never.” So, who was John Dahlgren and why are the Navy laboratory and town named after him?

John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren was born in Philadelphia in 1809. His parents, Bernhard and Martha Dahlgren, were well educated and on the edge – geographically and financially – of Philadelphia society and he knew the children of the top families. His parents insisted that he be given a proper education and he received top grades in mathematics, science, and Latin at a Quaker school.

Dahlgren’s world changed when his father died in 1824 and left the family in dire financial straits. He applied for an appointment as a midshipman in the Navy but was turned down. He worked for a time as a church secretary and then decided to reapply. This time, however, Dahlgren did something different and, following a pattern that he used throughout his life and career, used outside influence. In this case, that of prominent citizens of Philadelphia and family friends.

He was appointed as a midshipman in February 1826 and in April was ordered to serve on the USS Macedonian, originally the HMS Macedonian, on a cruise to South America. That was followed by a cruise to the Mediterranean on the USS Ontario. So far, his career was much like that of any Midshipman but things were about to take a turn. His cruise was cut short by illness and he was sent home on the USS Constellation, one of the original six frigates ordered by the US Navy. He used his three months leave to go to the Norfolk Navy School to study for his promotion examination.

He passed and was assigned to the USS Sea Gull, a receiving ship in Philadelphia, as a passed midshipman.1 There were some advantages to such an assignment. First and most importantly, it counted as an assignment at sea. In the 19th century, promotion was by strict seniority and there was no mandatory retirement age. So, in addition to waiting your turn for promotion, it was necessary to build a resume. The most important part of a personal record was time at sea and, eventually, command at sea. Other advantages included easy duty with time to pursue other interests and the opportunity to live (and spend time) on shore rather than on the ship. Dahlgren, for example, studied law by reading and making notes on Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, an influential law text from the 18th Century.

In June 1833, he got sick again and took an unplanned years leave to recover his health. When he was returned to active duty in 1834, he was assigned to the United States Geodetic Survey as an assistant to the Superintendent Ferdinand Hassler. This took advantage of his skills in mathematics and science and was a turning point in his career. Hassler believed in continuing the education of his assistants and Dahlgren received the equivalent of a graduate education in mathematics from him. He excelled in his assignments and, as his responsibilities grew, he took on additional duties as a leader of a survey team. He quickly found that he was being paid half that of the civilian members of his team and campaigned for a promotion or pay increase. Both were turned down and, as before, Dahlgren used influence outside of the Department of the Navy and wrote a letter to his senator, who pressured the Secretary of the Navy on Dahlgren’s behalf.2 Shortly after, he received his promotion to lieutenant.

Unfortunately, the close work he was doing damaged his eyes and in 1837 he was sent to the naval hospital in Philadelphia for treatment. When his eyes did not improve he requested leave to go to Paris – on full pay – for treatment. Dahlgren spent six months there but, again, there was little improvement. He was offered a choice – go to sea and possibly lose his sight or go on furlough at half pay. He objected to half pay on the basis that he had a service-related injury. After his proposal was rejected, he appealed to his congressman who had the decision reversed. He stayed on leave until 1842.

While his eyesight did not improve in Paris, it was another turning point in his career. He became acquainted with the work that Henri Joseph Paixhans was doing with the French Navy on a type of cannon that could fire an explosive shell. Dahlgren studied Paixhans’s work and wrote and self-published a translation of his work after returning from Paris. He distributed it to Navy officers which established his reputation as an ordnance expert. When he returned to active duty and was assigned to the USS Cumberland, he was a division officer and responsible for the Cumberland’s four shell guns. While on the USS Cumberland, he invented a simpler breech lock for the guns and an improved method for sighting guns, which added to his reputation as an ordnance expert. The cruise was cut short by anticipation of war with Mexico and he returned to Philadelphia in late 1846 and awaited orders. They came in January 1847 when Dahlgren was assigned to the Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography at the Washington Navy Yard.

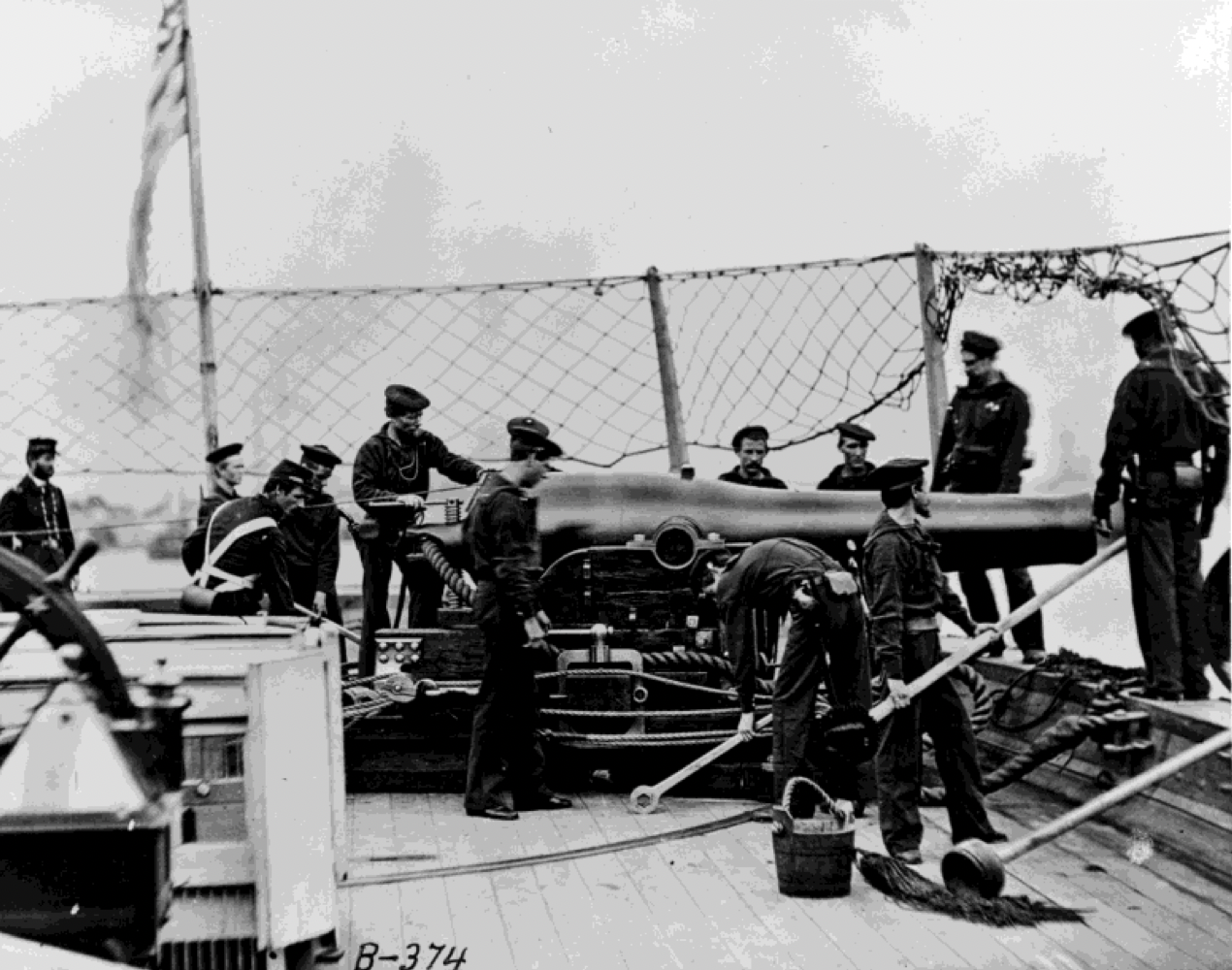

For the next five years Dahlgren applied the mathematics and science that he learned from Hassler to the development of ordnance. During that time, he established the Experimental Test Battery at the Navy Yard and he used the data that were gathered through testing in a scientific approach to designing naval guns.

The result was the famous soda bottle-shaped Dahlgren gun. He also assigned Navy officers to the foundries where the guns were made and applied his knowledge to develop a more rigorous approach to the acceptance of the guns by the Navy.

In 1861, the Commandant of the Navy Yard, Captain Franklin Buchanan, a Maryland native, resigned his commission on the belief that Maryland would secede. When that didn’t happen, he offered to withdraw his resignation. His offer was turned down and he “went south” and joined the Confederate Navy.3

Buchanan’s logical successor was Commander Dahlgren, but Commandant was a captain billet and his promotion was not likely. Promotion to captain usually followed a command tour at sea and Dahlgren had not been to sea in several years and had never had a command tour. His friend President Abraham Lincoln intervened and convinced Congress to pass a Special Act to promote him over the Navy’s objections.

A similar thing happened seven months later. Dahlgren wanted command at sea and Lincoln used his influence to have Dahlgren promoted to rear admiral and assigned to command the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron off Charleston, South Carolina to replace Rear Admiral Samuel F. DuPont in 1863.

But it was not easy or without controversy. Dahlgren had been pushing Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles for assignment to sea duty for a year and Welles had resisted on the grounds that Dahlgren was more valuable in his ordnance assignment. When he was promoted and saw that DuPont was in disfavor because of his failure in Charleston, Dahlgren saw an opportunity. He approached Welles about replacing DuPont. Welles felt that Dahlgren’s selection would cause resentment within the officer corps but, at the same time, knew that it would please the president. Welles resented Dahlgren’s relationship with Lincoln and saw it as an opportunity to get Dahlgren out of Washington and away from the president. His compromise was to appoint Rear Admiral Andrew H. Foote to command the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron with Dahlgren in a subordinate role commanding the ironclads. Foote and Dahlgren prepared to take command and met with Brigadier General Quincy A. Gillmore, the newly assigned army commander in South Carolina, to discuss his plan to capture Charleston. Foote fell ill and when he died, Welles felt that because Dahlgren was familiar with Gillmore’s plan, he was the best choice to succeed him.

Dahlgren had three missions when he took command: (1) capture Charleston, (2) blockade the South Atlantic Coast, and (3) defend the fleet and base at Port Royal. However, he was given only one specific instruction by Welles – support the Army and General Gillmore in conducting his operations. When he took command, he found that Gillmore’s first operation was to take place in just a few days. Dahlgren jumped in to support him and, while he felt that the Navy performed admirably, he saw the first signs of the problems that were to trouble him for most of the rest of the war. Dahlgren supported Gillmore’s joint army-navy plan but thought there needed to be a single overall commander. Dahlgren commanded the navy force while Gillmore commanded the army. Each felt free to do what they thought was right and, as a result, coordinated effort was problematic.

There were also personality issues. Welles had long thought that Dahlgren’s push for sea duty was motivated by a search for the glory that he could not get in a shore assignment. Since that required protecting his reputation, he was reluctant to take chances and quick to avoid taking responsibility for failure. Unfortunately, Gillmore displayed many of the same characteristics. That eventually led to a feud that colored Dahlgren’s postwar years. The end result was a number of army operations that accomplished relatively little and, in any case, did not lead to the capture of Charleston.

In the fall of 1863, Dahlgren told Welles, who agreed with his assessment, that he could not undertake inner harbor operations at Charleston, as desired by Gillmore, with the forces at his disposal. He said that he could do so with additional ironclads. Welles agreed but noted that it would be several months before new ironclads would be available. However, by the end of the year, the War Department and the Navy Department both decided there were higher priorities and that there would not be any future efforts to capture Charleston.

Dahlgren’s focus the rest of the year was on blockading efforts and maintaining a stalemate in Charleston. During this time, he offered to resign three times. Welles attributed the offers to Dahlgren’s “glory seeking” and rejected all of them. He also saw possible political problems if he accepted Dahlgren’s resignation and still wanted to keep Dahlgren out of Washington.

Late in the year, General Sherman was approaching Savannah and Dahlgren saw an opportunity to support him through amphibious operations on the Georgia coast. Dahlgren had a longstanding interest in amphibious operations and had previously developed a small boat howitzer and the Model 1861 Navy (or “Plymouth”) rifle for shipboard and amphibious use. He also developed a manual for amphibious operations that included a fleet force of trained sailors and marines and incorporated artillery. Many of the elements of amphibious operations that he pioneered, tested, and revised are now widely accepted. He later supported Sherman’s move to bypass Charleston by providing a naval distraction. He occupied Charleston in February 1865 and spent the remaining months of the war removing obstructions in harbors and, finally, disbanding his squadron. He relinquished command in July and returned to Washington.

He spent some time in Washington before taking command of the South Pacific Squadron in 1866. He returned to Washington in 1868 and served as Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance for a year and then as Commandant of the Washington Navy Yard until his death in 1870.

In retrospect, some of Welles’s concerns were borne out. Senior navy officers respected Dahlgren for his work in ordnance but, as Welles suspected, resented his use of relationships and politics to get successes that they felt he had not earned. It should be said that he had some success while commanding the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron and, to one degree or another, he accomplished his three objectives. He also developed an understanding of joint operations and pioneered amphibious operations. He was a prolific writer and authored a number of books on ordnance and one on amphibious operations.

On the negative side, his conflict with Gillmore shaped his life from the end of the Civil War until his death. He spent much effort defending his reputation from charges from Gillmore and others and “refought” Charleston often during those years. As a result, his contributions to learning the lessons of the recent war and further contributions to ordnance were few.

Dahlgren’s Legacy Lives On

John Dahlgren left a rich legacy in the development, acceptance, and testing of naval ordnance. He established the Experimental Test Battery at the Washington Navy Yard for those purposes. His legacy was preserved after his death when the Naval Proving Ground (NPG) was established in Annapolis, Maryland in 1872 and then moved to Indian Head, Maryland in 1890. The focus of the NPG was on the same things that concerned Dahlgren although Indian Head branched out, especially during World War I, and produced smokeless gunpowder and tested rockets. However, technology overtook the capabilities of the Indian Head river range and by 1917, the need for a larger testing range for the Naval Proving Ground had become critical.

Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, championed the effort to relocate the range from Indian Head. In 1918 an auxiliary test range was created at Dido, in King George County, Virginia, that was called the Lower Station of Indian Head. Earle thought that an appropriate name was needed for the post office at the new site. He persuaded Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels to request the U.S. Postal Service to change the name of the existing Dido post office to Dahlgren to honor the “Father of American Naval Ordnance,” with the change happening in 1919. Most of the testing moved to Dahlgren and, in 1932 the Lower Station officially became the Naval Proving Ground and Indian Head became the Naval Powder Factory.

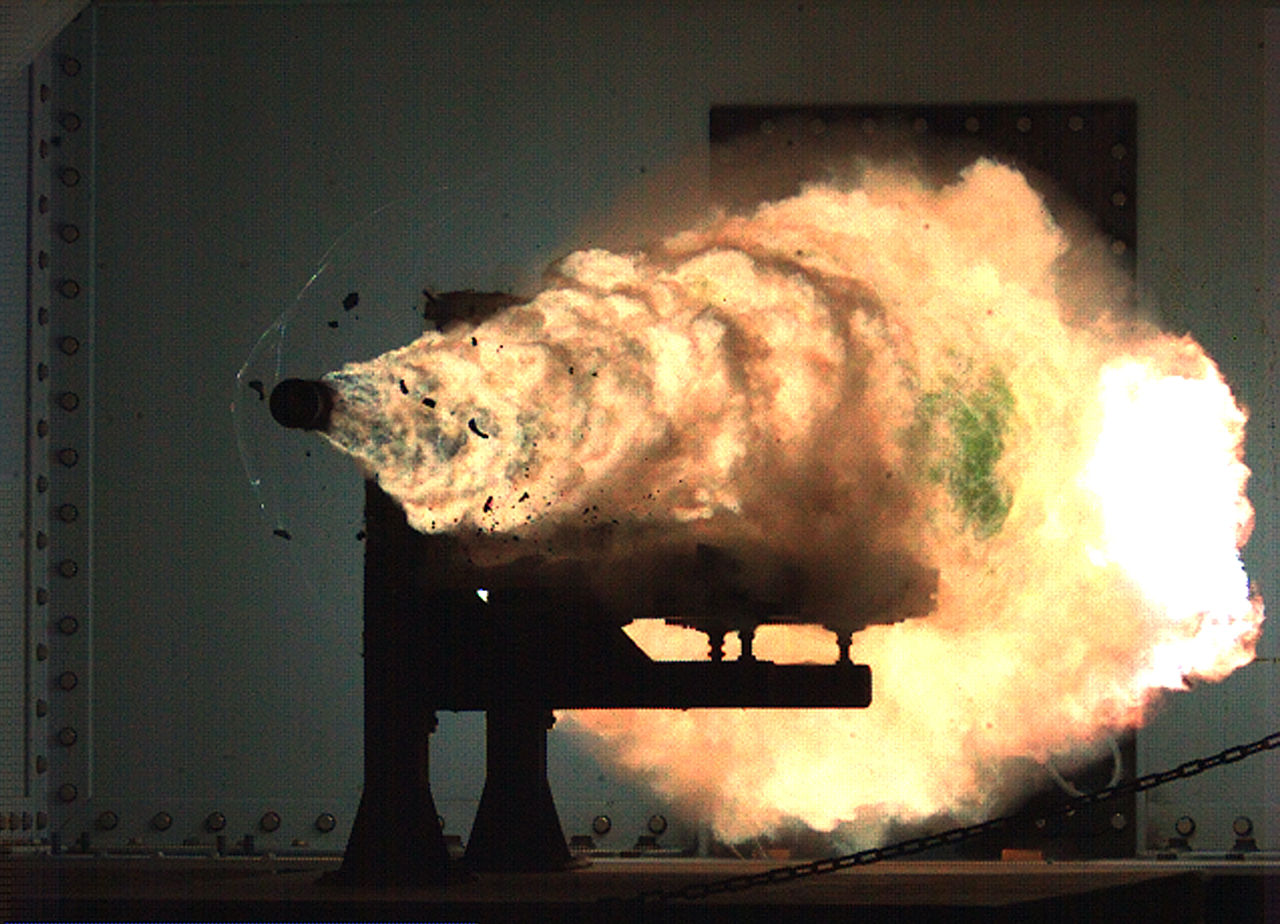

The site at Dahlgren was originally established to test large caliber naval guns but has tested all sizes and calibers of navy guns – from 18 inches down – and, more recently, the electromagnetic railgun. Testing peaked during World War II and again, but at a lower level, during the Vietnam years. Dahlgren was the only place to fire 16-inch guns when the battleships were reactivated in the 1980s. The Navy has said that nearly 350,000 rounds were fired at Dahlgren between 1918 and 2007, averaging 3,800 rounds fired per year.

Dahlgren’s mission expanded from ordnance testing to research and development when Dr. L.T.E. Thompson came in 1923. It has continued and has included such things as work on laser-guided projectiles in the 1970s. Other things were also happening in Dahlgren. Aviation work came to Dahlgren in 1919 and stayed until World War II. Work included development and testing of unmanned airplanes, the Norden bombsight, and bombs. Dahlgren’s efforts in gunnery were computation-intensive and one of the most powerful computers of the day, the Aiken Relay Calculator, came to Dahlgren and, several years later, was replaced by the Navy Ordnance Research Calculator. Dahlgren’s computer capability led to new opportunities in ballistics, orbital mechanics, and missiles.

There have been challenges to both the Dahlgren site and the river range. Dahlgren met many of the challenges by broadening its mission to take advantage of its capabilities to meet emerging Navy needs, including in lasers and unmanned vehicles. Eventually, expertise in these new areas led to the current focus on systems engineering.

Through all of the changes and challenges, the Potomac River Test Range – “the nation’s largest fully instrumented over-water gun-firing range” – has remained an important part of Dahlgren’s mission. During each of the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) studies, the range was a key element in Dahlgren’s responses and the cornerstone that preserved Dahlgren’s location.

The most recent challenge is a June 2023 lawsuit filed by environmental groups concerned with the potential pollution of the river from weapons testing. A settlement was reached in January 2024 when the Navy agreed to seek a “permit for discharges of pollutants” from the state of Maryland.

As capabilities and scope of work grew over the years, the name of the organization changed to reflect its changing mission. In 1992, the name was changed to the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division.

So, John Dahlgren was not born here and never served here but the Division is his legacy and, so, his name lives on.

Robert V. (Rob) Gates, a retired Navy Senior Executive, served as the Technical Director at the Naval Surface Warfare Center (NSWC), Indian Head Division, and in many technical and executive positions at NSWC, Dahlgren Division, including head of the Strategic and Strike Systems Department. He holds a B.S. in Physics from the Virginia Military Institute, a Masters in Engineering Science from Penn State, and a Masters and PhD in Public Administration from Virginia Tech. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College. Dr. Gates is the Vice President of the board of the Dahlgren Heritage Foundation.

Notes

1. A ship that was past its useful life and no longer seaworthy could be converted into a receiving ship. It would be permanently tied up at a harbor or navy yard and used for inducting (“receiving”) and training newly recruited sailors.

2. Seniority was a problem. A midshipman appointed in 1839 could expect to be promoted to lieutenant in 1870. Promotion also required assignment to a position that supported the rank. Dahlgren fell short in both regards.

3. Buchanan was commissioned a Captain in the Confederate Navy and commanded the CSS Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimack) against the USS Congress and USS Cumberland in the Battle of Hampton Roads. He was wounded and was not in command against the USS Monitor. He was later promoted to full admiral, the only one in the Confederate Navy.

4. The range of the 14 and 16-inch guns being developed for battleships could only be tested under limited conditions at Indian Head. In addition, there were some testing-related incidents.

5. In 1914, Secretary Daniels issued General Order Number 99 which prohibited alcohol (for drinking) onboard navy ships. As a result, purchases of coffee increased and sailors reportedly referred to it as “a cup of Josephus Daniels” which was later shortened – and better known – as “a cup of Joe.”

References

Browning, Robert M. Jr. “The Early Architect of Amphibious Doctrine.” Naval History Magazine. April 2019.

Bruns, James H. “John A. Dahlgren: Lincoln’s Seasick Naval Genius.” Sea History. Autumn 2016, 20-25.

Craig, Lee A. Josephus Daniels: His Life and Times, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Dahlgren, Madeleine Vinton. Memoir of John A. Dahlgren. Boston: James B. Osgood and Company, 1882.

Luebke, Peter C., Ed. The Autobiography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren. Washington Navy Yard, D.C.: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2018.

Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division, Water Range Sustainability Environmental Program Assessment, May 2013.

Rife, James P. and Rodney P. Carlisle. The Sound of Freedom: Naval Weapons Technology at Dahlgren, Virginia 1918-2006. Dahlgren, VA: NSWCDD, 2007.

Schneller, Robert J. Quest for Glory: A Biography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996

Symonds, Craig L. Confederate Admiral: The Life and Wars of Franklin Buchanan. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008.

Taaffe, Stephen R. Commanding Lincoln’s Navy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2009.

Featured Image: A 14-inch gun fires a test round down range, during World War II. (Photo via U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)