By Sebastian Bruns and Sarah Kirchberger

On 19 July 2017, after a long transit through the Indian Ocean and around the European continent, a three-ship People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) task group entered the Baltic Sea to conduct exercises with the Russian Navy (RFN). The flotilla reached Kaliningrad, the exercise headquarters, on July 21st. While hardly the first time that China’s naval ensign could be spotted in this Northern European body of water (for instance, a Chinese frigate participated in Kiel Week 2016), “Joint Sea 2017” marks the first ever Russo-Chinese naval drill in the Baltic Sea. The exercise raised eyebrows in Europe, and NATO members scrambled to shadow the PLAN ships on their way to the Baltic and carefully monitor the drills.

The timing in July was not a coincidence, given that relations between the West and East – however broadly defined – increasingly have come under strain. Mirroring a decidedly more robust maritime behavior in the Asia-Pacific, this out-of-area exercise also signals an increasingly assertive and maritime-minded China. The PLAN has been commissioning advanced warships in higher numbers than any other navy during 2016 and 2017, and is busy building at least two indigenous aircraft carriers. Earlier this summer, the PLAN opened its first permanent overseas logistics base in Djibouti, East Africa. The maritime components of the Chinese leadership’s ambitious “Belt & Road Initiative”– which includes heavy investments in harbors and container terminals infrastructures along the main trading routes – furthermore demonstrate the Chinese intent to play a larger role in global affairs by using the maritime domain. Is the Chinese Navy’s increased presence in the Indian Ocean and in European waters therefore to become the “new normal”?

In the following essay, we argue that context matters when looking at these bilateral naval drills, and we seek to shed some light on the particulars revolving around this news item. In our view, it is important to review the current exercise against the general trajectory of Chinese naval modernization and expansion in recent years on the one hand, and of steadily deepening Russo-Chinese cooperation in the political, military, military-technological, and economic spheres on the other. We seek to offer some talking points which give cause for both relaxation and concern, and conclude with policy recommendations for NATO and Germany.

The Current Drills and Their Background

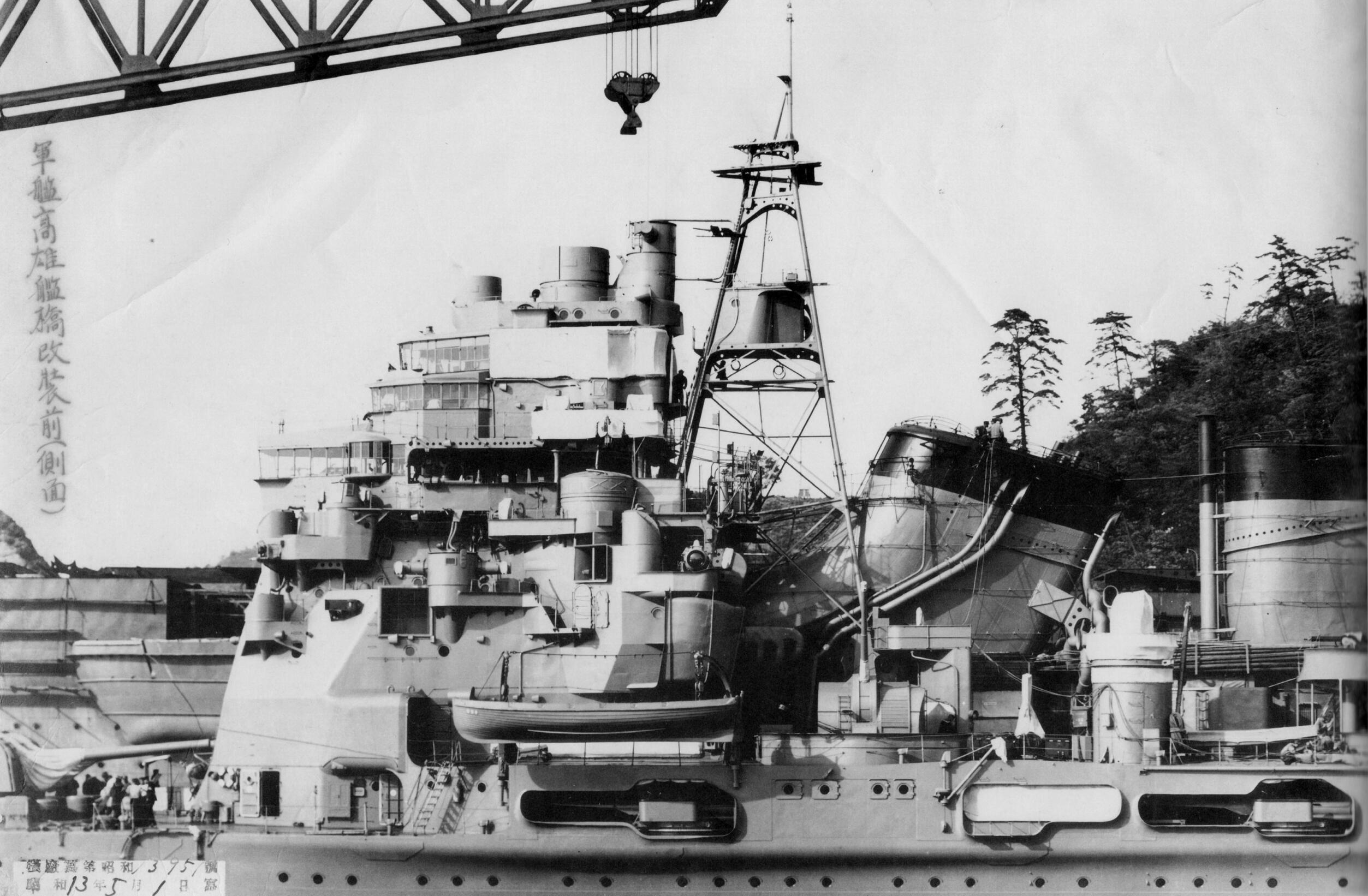

The July 2017 naval exercise with Russia in the Baltic Sea is the PLAN’s first ever excursion into this maritime area for a formal deployment. For China, it’s an opportunity to showcase the PLAN’s latest achievements in naval technology and shipbuilding prowess, which is perhaps why the Chinese task force includes some of its most advanced and capable surface warships: the PLAN’s Hefei (DDG-174), a Type 052D guided-missile air warfare destroyer featuring the “Chinese AEGIS”; the Yuncheng (FFG-571), a Type 054A guided-missile frigate; and a Type 903-class replenishment oiler from China’s Southern Fleet, the Luomahu (AOR-964). Originally the destroyer Changsha (DDG-173) had been scheduled for this exercise, but had to be replaced by its sister ship the Hefei after it suffered an apparent engine malfunction in the Indian Ocean while on transit from Hainan.

Simultaneous Excursions into Northern and Southern European Waters

It is probably not a coincidence that China has sent another three-ship task group to the Black Sea during the exact same timeframe. There, the PLAN’s Changchun (DDG-150), a Type 052C destroyer capable of carrying 48 long-range HHQ-9 missiles, the Jingzhou (FFG-532), a newly-launched Type 054A frigate, and the logistics support vessel Chaohu (AOR-890) have docked at Istanbul over the weekend under heavy rain. This excursion comes on the heels of the 17th Sea Breeze maneuvers that saw Ukrainian, Romanian, Bulgarian, and NATO warships exercise together between July 10-22. Similarly, the Russo-Chinese Baltic Sea war games were scheduled to be held just four weeks after BALTOPS, a large annual U.S.-led multi-national naval exercise which until 2013 had included Russian participation under the Partnership for Peace (PfP) arrangements.

Just two weeks earlier Germany, the Baltic Sea’s largest naval power, had hosted the G-20 talks in Hamburg. When Australia hosted the G-20 summit in 2014, the Russian Navy deployed its flagship Varyag to the South Pacific. It is therefore sensible to assume a deliberate timing of the Chinese-Russian Baltic exercises, which are intended as a signal to NATO members and to the Baltic Sea’s coastal states. Russia, after all, sent two of its mightiest warships to “Joint Sea 2017”: The Typhoon-class Dmitry Donskoy, the world’s largest submarine, and the Russian Navy’s largest surface combatant, the Kirov-class nuclear powered battlecruiser Pyotr Velikiy, both highly impractical for the confined and shallow Baltic Sea.

Regular Russo-Chinese naval exercises commenced in April 2012, when the first-ever joint naval drills were held in the Yellow Sea near Qingdao. Bilateral naval exercises have since been conducted every year.

As Table 1 shows (at bottom), the scope and complexity of these drills have steadily increased. Jane’s Defence Weekly reported that during the 2016 exercises, a joint command information system was used for the first time to improve interoperability and facilitate shared situational awareness. This is remarkable given that China and Russia are not formal military allies as of yet. What does this development indicate?

Ambitious Naval Modernization Plans in Russia and China

In terms of naval capability, China and Russia are aiming to recover or maintain (in the case of Russia) and reach (in the case of China) a true blue-water proficiency. After decades of degradation, the Russian Navy hopes to enlarge its surface fleet, retain a minimum carrier capability, and maintain a credible sea-based nuclear deterrence capability. So far, Russia talks the talk but fails to walk the walk. The PLAN is meanwhile hoping to transform itself into a fully “informationized” force capable of net-centric operations; it is planning to operate up to three carrier groups in the mid-term, and is developing a true sea-based nuclear deterrent for which submarine incursions into the West Pacific and Indian Ocean (and maybe even into the Arctic and Atlantic) will be essential, since China’s sub-launched missiles can’t threaten the U.S. mainland from a bastion in the South China Sea.

Apart from developing, producing, and commissioning the necessary naval hardware, these ambitious goals require above all dedicated crew training in increasingly frequent and complex joint operations exercises in far-flung maritime areas. For Russia, the Joint Sea exercise series can function as a counterweight to the U.S.-led annual BALTOPS exercises (where they are no longer a part of) and a replacement for the FRUKUS exercises conducted during the 1990s and 2000s with France, the U.K., and the U.S. China has been slowly building experience with out-of-area deployments through its naval patrols off the Horn of Africa, which culminated in the establishment of China’s first overseas logistics hub in Djibouti earlier this year. So far China’s footprint in the world is nevertheless mainly economic, not military, as China still lacks military allies and does not have access to a global network of bases that could facilitate a truly global military presence. In the context of protecting Chinese overseas investments, installations, personnel deployments and trade interests, a more frequent naval presence in European waters can nevertheless be expected.

Potential Areas of Concern

From NATO’s and Europe’s vantage point, one thing to monitor is the prospect of a possible full-blown entente between Russia and China following a period of increasing convergence between Chinese and Russian economic, military, and strategic interests. Traditionally, relations between both countries have been marred by distrust and strategic competition. Russian leaders likely still fear China’s economic power, and are wary of a possible mass migration movement into Russia’s far east, while China is dependent on Russian cooperation in Central Asia for its ambitious Belt & Road Initiative. Russia is militarily strong, but economically weak, with resources and arms technologies as its main export products, while China is an economic heavyweight, but has lots of industrial over-capacities and is in need of importing the type of goods that Russia has to offer. Especially after the Western sanctions kicked in, Russia needs Chinese capital to continue its ambitious minerals extraction projects in the Arctic, while China continues to rely on some Russian military high-technology transfers, e.g. in aerospace and missile technologies. Cash-strapped Russia has ambitious naval procurement plans of its own that were hampered by its loss of access to Ukrainian and Western arms technologies, while China, having faced similar Western arms embargo policies since 1989, is now on a trajectory of significant fleet enlargement and, unlike Russia, has the financial resources to pay for it. Possible synergies in the naval area include diesel submarine design and construction, given China has reportedly expressed interest in acquiring Russian Lada- or Kalina-class subs.

Furthermore, both governments have strong incentives to cooperate against what they perceive as “Western hegemonialism.” Both reject the universal values associated with the Western liberal order and reserve the right to “solve” territorial conflicts within their periphery that are deemed threatening to their “core interests” by military means. Both governments are furthermore keen to preserve their power to rule by resisting urges from within their societies to transform, and they invariably suspect Western subversion attempts behind any such calls. Since both are subject to Western arms embargoes that have in the past caused disruption of large-scale arms programs, including in the naval domain, the already strong arms trade relationship between China and Russia has been reinforced through new deals. One side-effect of this long-standing arms trade relationship is a technological commonality between both militaries that furthers interoperability.

Enhancing bilateral mil-tech cooperation and cooperating more strongly in natural resources development therefore offers Russia and China multiple synergies to exploit, and the results can already be seen: After the Western shunning of Russia in the wake of the Crimea crisis in 2014, several large-scale arms and natural resources deals have been concluded between Putin’s Russia and Xi’s China, and the cooperation projects between China and Russia in the Arctic (mostly related to raw materials extraction) have now officially been brought under the umbrella of the vast, but somewhat diffuse Chinese Belt & Road Initiative. The recently concluded Arctic Silk Road agreement between China and Russia seems to indicate that China has somehow managed to alleviate Russian fears of Chinese naval incursions in the Arctic waters.

In sum, the longstanding Western arms embargo against China, combined with Western punitive sanctions against Russia since 2014, as well as unbroken fears in both countries of Western subversion through a strategy of “peaceful evolution“ (as employed during the Cold War against the Soviet Union), plus the perceived threat of U.S. military containment, creates a strong set of incentives on both sides to exploit synergies in the economic, diplomatic, and military realm. “Russia and China stick to points of view which are very close to each other or are almost the same in the international arena,” Putin said during a visit to China in 2016. The fact that Chinese internet censorship rules were recently amended to shield Putin from Chinese online criticisms, the first time a foreign leader was extended such official “protection,” further indicates a new level of intimacy in the traditionally strained relationship. It can therefore be assumed that both countries will continue their cooperation in the political and diplomatic arenas, e.g. within the U.N. Security Council.

Finally, both countries face a structurally similar set of security challenges. Internally, they are mainly concerned with combating separatism and internal dissent, and externally they fear U.S. military containment and Western interference in their “internal affairs.” The latter is addressed by both countries in a similar way by focusing on asymmetric deterrence concepts (A2/AD bubbles) on the one hand and nuclear deterrence on the other. Russia’s Kaliningrad enclave, the headquarters of the current “Joint Sea 2017” exercise, is the cornerstone of the major Russian A2/AD bubble in Northern Europe. Furthermore, Russia’s traditional Arctic bastion concept for its strategic submarines is now likely echoed in Chinese attempts to make parts of the South China Sea into a bastion for the Chinese SSBN force. It should also be noted that both countries have also recently resorted to somewhat similar hybrid strategies in their dealings with smaller neighboring countries within their “spheres of influence” – a curious commonality. Russia’s “little green men” find their maritime counterpart in China’s “little blue men,” government-controlled maritime militia-turned-fisherman who are staging incidents in the South China and East China Seas.

To sum up, the steadily deepening mil-tech cooperation on the basis of past arms transfers have by now resulted in a certain degree of technical commonality, and regular joint exercises have recently been conducted with the explicit aim of adding a training component in order to achieve better interoperability. Their similarities in threat perception mean that both countries can benefit from exchanging information and experiences in areas such as hybrid warfare, A2/AD (or “counter-intervention”) strategies, and AAW and ASW missions. Even in the absence of a formal military alliance, these developments merit closer watchfulness by NATO and the Western navies, especially when seen in context with the common political interests and matching world perception shared by these two authoritarian countries.

What Challenges does this Pose to NATO in Particular?

While the exercise is not as such problematic and takes place in international waters that are open to any navy, there are some implications for NATO to consider. If this emerging naval cooperation deepens further, and bilateral Russo-Chinese drills in NATO home waters should become more frequent, then this could mean that NATO’s limited naval resources will increasingly come under strain. Shadowing and monitoring Chinese and Russian vessels more often implies dispatching precious vessels that would be needed elsewhere. This could in fact be one of the main benefits from the point of view of Russia and China. Some NATO navies have in the past expressed a willingness to support the U.S. in the South China Sea, which China considers to be part of its own sphere of interest. Putting up the pressure in NATO’s own maritime backyard could therefore serve the purpose of relieving U.S. and Western pressure on China’s Navy in its own home waters. In that sense, to adapt an old Chinese proverb, the Baltic exercise could be seen as an attempt to “make a sound in the West and then attack in the East.” On the other hand, Russian-Chinese exercises give NATO navies a chance to observe Chinese and Russian naval capabilities more closely, which can over time contribute to alleviating some of the opacity surrounding China’s naval rise. It will also help propel fresh thinking about the future of NATO maritime strategy and the Baltic.

Policy Recommendations

First, the exercise should be interpreted mainly as a form of signaling. As James Goldrick pointed out,

“A Chinese entry into the Baltic demonstrates to the U.K. and France in particular that China can match in Europe their efforts at maritime presence in East Asia (…) and perhaps most significant, it suggests an emerging alignment between China and Russia on China’s behavior in the South China Sea and Russia’s approach to security in the Baltic. What littoral states must fear is some form of Baltic quid pro quo for Russian support of China’s artificial islands and domination of the South China Sea.”

Second, the possibility of Russia and China forming a military alliance of sorts should be more seriously analyzed and discussed, as such a development would affect the strategic calculations surrounding a possible military confrontation. China has long been concerned with the problem of countering the U.S.-led quasi-alliance of AEGIS-equipped navies on its doorstep (South Korea, Japan, Australia, and the U.S. 7th Fleet), and some noted Chinese intellectuals (such as Yan Xuetong) have publicly argued in favor of China forming military alliances and establishing military bases in countries it has an arms trade relationship with. It is not hard to see that such remarks could have been made first and foremost with Russia in mind, China’s most militarily capable arms trade partner. Remote as the possibility might seem to some, the potential of such a development alone should concern NATO and all European non-NATO states, especially given Europe’s strong economic involvement with China.

Third, while it is hard to see how the arms embargoes against Russia and China could be lifted in the near and medium term, given both countries’ unwillingness to accept the right of smaller countries in their respective “sphere of interest” for unimpeded sovereignty, Western countries should more seriously analyze the impact that these sanctions have so far had in creating incentives for an entente, and find ways to engage China and Russia constructively in other areas to provide an alternative to a Russo-Chinese marriage of convenience.

Fourth, the German Navy and other Baltic forces should use this and future Chinese excursions into the Northern European maritime area mainly as an opportunity to gather intelligence, and to engage the Chinese Navy in the field of naval diplomacy. For Germany, it is also high time to start planning in earnest the replacement of the Oste-class SIGINT vessels, to expedite the procurement of the five additional Braunschweig-class corvettes, and to properly engage with allies in strategic deliberations regarding the Baltic Sea in a global context.

The authors work for the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University (ISPK), Germany. Dr. Sarah Kirchberger heads the Center for Asia-Pacific Strategy & Security (CAPSS) and is the author of Assessing China’s Naval Power: Technological Change, Economic Constraints, and Strategic Implications (Springer, Berlin & Heidelberg 2015). Dr. Sebastian Bruns directs the Center for Maritime Strategy & Security (CMSS) and is editor of the Routledge Handbook of Naval Strategy & Security (London 2016).

Table 1: Major PLAN-RFN bilateral exercises

|

Designation/ Timeframe |

Region | Major Units |

Type of missions |

| “Sino-Russian Naval Co-operation 2012” (April 22-27) | Yellow Sea / near Qingdao | China: 5 destroyers, 5 frigates, 4 missile boats, one support vessel, one hospital ship, two submarines, 13 aircraft, five shipborne helicopters

Russia: Slava-class guided missile cruiser Varyag, 3 Udaloy-class destroyers. |

AAW. ASW. SAR MSO, ASuW |

| ‘Joint Sea 2013’

(July 7-10) |

Sea of Japan / Peter the Great Bay near Vladivostok | China: Type 052C (Luyang-II class) destroyer Lanzhou; Type 052B (Luyang I-class) destroyer Wuhan; Type-051C (Luzhou-class) destroyers Shenyang and Shijiazhuang (116); Type 054A (Jiangkai-II class) frigates Yancheng and Yantai; Type 905 (Fuqing-class) fleet replenishment ship Hongzehu.

Russia: 12 vessels from the Pacific Fleet. |

air defence, maritime replenishment, ASW, joint escort, rescuing hijacked ships

|

| ‘Joint Sea 2014’

(May 20-24) |

East China Sea / Northern part | China: Russian-built Sovremenny-class destroyer Ningbo; Type 052C (Lüyang II class) destroyer Zhengzhou

Russia: Missile cruiser Varyag plus 13 surface ships, 2 submarines, 9 fixed-wing aircraft, helis and special forces. |

ASuW, SAR, MSO, VBSS

anchorage defense, maritime assaults, anti-submarine combats, air defense, identification, rescue and escort missions |

| ‘Joint Sea 2015’ Part I’ (May 18-21) | Eastern Mediterranean | China: Type 054A frigates Linyi and Weifang, supply ship Qiandaohu

Russia: six ships including Slava-class destroyer Moskva , Krivak-class frigate Ladny , plus 2 Ropucha-class landing ships |

Navigation safety, ship protection, at-sea replenishment, air defense, ASW and ASuW, escort missions and live-fire exercises |

| ‘Joint Sea 2015’ Part II (August 24-27) | Sea of Japan / Peter the Great Gulf near Vladivostok | China: Type 051C Luzhou-class destroyer Shenyang, Sovremenny-class destroyer Taizhou, Type 054A Jiangkai II-class frigates Linyi and Hengyang, amphibious landing ships Type 071 Yuzhao-class (LPD) Changbaishan and Type 072A Yuting II-class (LST) Yunwunshan, Type 903A Fuchi-class replenishment ship Taihu; PLAAF units: J-10 fighters and JH-7 fighter-bombers

Russia: Slava-class cruiser Varyag and Udaloy-class destroyer Marshall Shaposhnikov, two frigates, four corvettes, two subs, two tank landing ships, two coastal minesweepers, and a replenishment ship. |

ASW, AAW, amphibious assault, MCM |

| ‘Joint Sea 2016’ (September 12-20) | South China Sea / coastal waters to the east of Zhanjiang | China: Luyang I-class (Type 052B) destroyer Guangzhou, Luyang II-class (Type 052C) ; destroyer Zhengzhou; Jiangkai II-class (Type 054A) frigates Huangshan, Sanya and Daqing, Type 904B logistics supply ship Junshanhu, Type 071 LPD Kunlunshan, Type 072A landing ship Yunwushan, 2 submarines; 11 fixed-wing aircraft, eight helicopters (including Z-8, Z-9 and Ka-31 airborne early warning aircraft) and 160 marines with amphibious armoured equipment.

Russia: Udaloy-class destroyers Admiral Tributs and Admiral Vinogradov; Ropucha-class landing ship Peresvet; Dubna-class auxiliary Pechanga and sea-going tug Alatau plus two helicopters, 96 marines, and amphibious fighting vehicles. |

SAR, ASW, joint island-seizing missions, amphibious assault, live firings, boarding, air-defense

|

| ‘Joint Sea 2017’ (July 21-28) | Baltic Sea / off Kaliningrad | China: Type 052D destroyer Hefei, Type 054A frigate Yuncheng, Type 903A replenishment ship Luomahu

Russia: 2 Steregushchy class corvettes, one support tug, naval Ka-27 helicopters and land-based Su-24 fighter-bombers as air support. |

SW, AAW, ASuW, anti-piracy, SAR |

Featured Image: In this photo released by China’s Xinhua News Agency, officers and soldiers of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy hold a welcome ceremony as a Russian naval ship arrives in port in Zhanjiang in southern China’s Guangdong Province, Monday, Sept. 12, 2016.