By Ian Birdwell

Introduction

This June has been unsettling for the Arctic. Russia experienced three events the Arctic Council has been dreading for years: an oil spill, an outbreak of wildfires, and the hottest Arctic temperature record being set with a 100-degree Fahrenheit day in Siberia. However, Russia is not alone in addressing these events. The Arctic Council, the Arctic’s premier multilateral organization, has sought to prepare the region and the globe for the eventuality of a warmer Arctic.

These recent events bring into focus both the work the Council has done to promote regional governmental frameworks and the long road that remains ahead for fulfilling its mission of monitoring the Arctic environment. The Council has not been idle since its founding in 1996 and is continually promoting active measures to ensure the Arctic environment is protected as the region warms and opens to increased economic activity, with a host of working groups, agreements, and policy recommendations coming forward to address concerns like oil spills and sea ice retreat. This summer represents a major test of the Arctic Council as these crises come at a time when the Arctic Council is being pulled in directions it would rather avoid. Tensions are rising between the two most powerful states on the Council, the United States and Russia, and calls to direct the Council to address rising Arctic militarization have grown from prominent leadership.

Historically, the Council has tempered its focus on issues it can resolve and gain regional coordination on, ranging from environmental research to new regional agreements, with each state of the Council doing their part to empower the institution to meet those communal goals through the acknowledgement of the Council’s limitations. With consideration of those limitations weakening as the region experiences its worst June yet, the Arctic Council finds itself in newly tense territory.

It becomes critical to examine this June from the perspective of improving Arctic Ocean governance to tackle these emerging environmental issues. Given the track record of the Arctic Council in developing regional frameworks, the solution lies with it and its member states. Particularly, acknowledging the Council’s limitations and its adopted role would enable the Council to do the job it has been designed to do in terms of providing coordination on scientific research, regulations, and indigenous representation instead of becoming another institutional battleground for international competition. Thus enabled, the Council would be able to further the quiet lead it has maintained on Arctic issues for more than 20 years in creating mutually acknowledged regulations for the Arctic’s waterways and in strengthening the overall international maritime regime.

Regional Facilitator and Forum

The Arctic Council began from efforts to preserve the Arctic environment in 1996, and today research coordination across all members and observers of the Arctic Council remains paramount. This marks the first area where members could assist in developing governmental frameworks for the Arctic region by empowering the Council through reaffirming its mission to coordinate regional scientific research. Scientific research coordinated by the Council enables member states to address emerging issues, act on new opportunities, and protect their communities.

The clearest example of such information dissemination is linked to the publication of the 2004 Arctic Climate Impact Assessment which renewed global interest in the potential of a warm Arctic and the plight of the unique environment of the polar region. This research is not glamorous and does not yield immediate results, yet it is fundamental to the establishment of effective regional policies for all member states in response to the increasing changes of the Arctic. Particularly, coordinating research enables a broader understanding of the regional transformation, a sharing of ideas and perspectives, and has stood the test of tensions in maintaining relationships in spite of broader international disagreements. In effect, the Council’s push toward scientific research has enabled states mostly concerned with the broader global environment to maintain Arctic policy flexibility without radically shifting their own domestic policies. This stability of research coordination could be disrupted by continued calls for the Council to address regional militarization, which in turn could negatively impact the collection and coordination of research within the Council’s network. Thus, recognizing the limitations of the Council in addressing emerging issues regarding militarization enables the continued functioning of scientific coordination and diplomacy in the high north and preserves domestic policymaking for Council members.

One of the most recognizable aspects of the Arctic Council is the inclusion of a variety of indigenous people’s organizations from throughout the Arctic region. This marks the second area where the Arctic Council could assist in furthering Arctic maritime governance as it has been critical in engaging the local indigenous communities. Climate change is ravaging the Arctic landscape in different ways, so the Arctic Council has been dedicated to ensuring the ways of life of the regional indigenous communities are preserved as best as possible and their voices are heard through the Arctic Council’s Permanent Participant organizations and the Indigenous People’s Secretariat. This engagement with the indigenous community has played a large part in the overall regional engagement of the Arctic Council, with the Council supporting critical issues like health, economic, and education initiatives alongside cultural preservation programs. In turn, these communities provide member states with experts offering deep knowledge of the local environment, climate conditions, and real-time impacts of climate change throughout the region, giving the Council critical on-the-ground information regarding how regional warming is impacting the Arctic.

As the Council is pushed to address issues like militarization and other dicey political issues, the indigenous communities of the Arctic could be pushed into the background as political capital is expended to address narrower national interests. This could inhibit the ability of the Council to address rising maritime issues like the endangerment of marine environments due to increased human activity or climate change, issues where indigenous communities are the most vulnerable and most aware of in the changing climate. Thus, there is the risk of the Council being unable to address problems noticed by indigenous populations if it focuses on addressing militarization or other issues heavily tied to the competing national interests of member states.

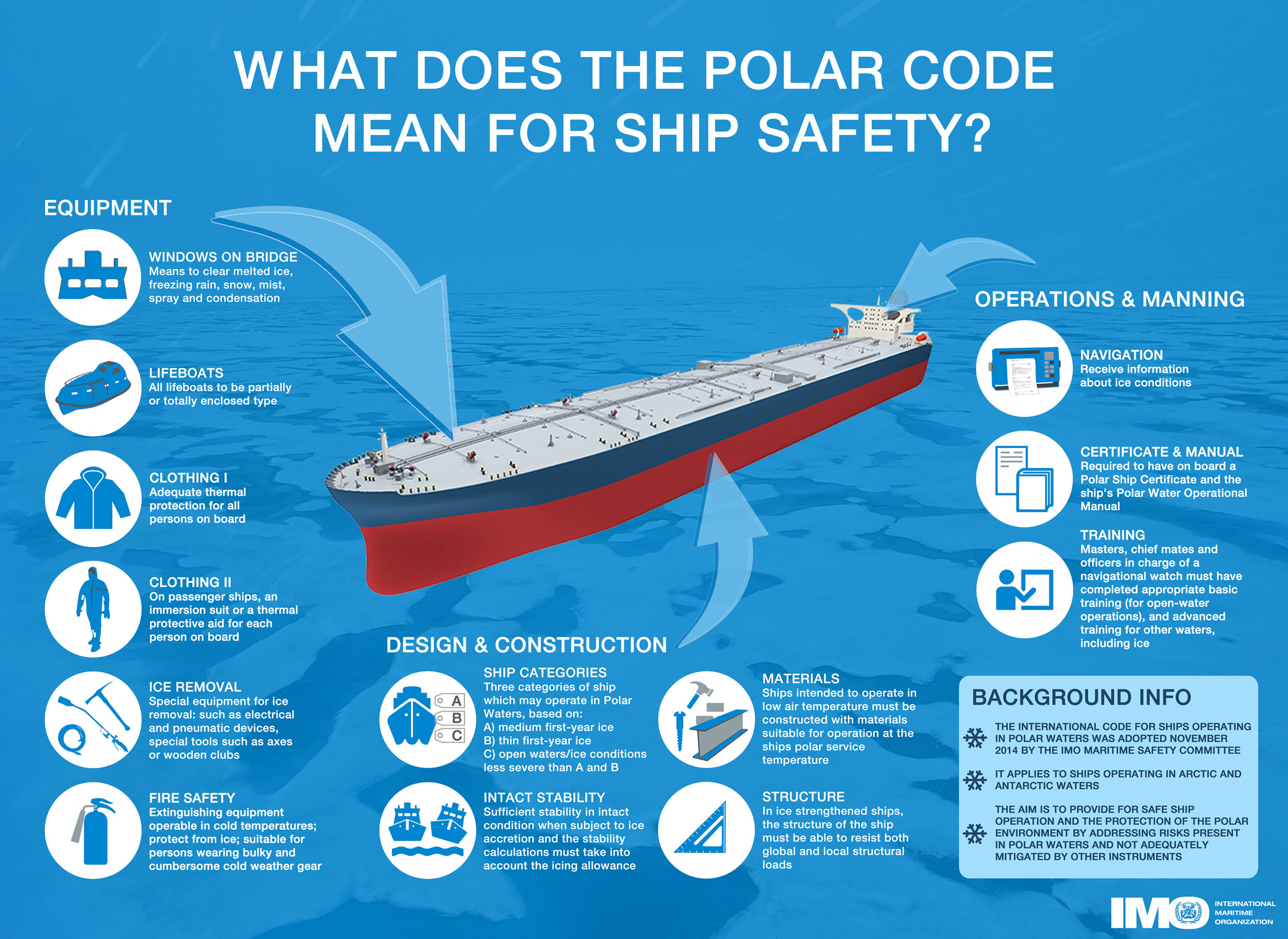

One of the crowning achievements of the Arctic Council in the past decade has been the establishment of a series of maritime shipping reports and regulations which were adopted by the International Maritime Organization as the Polar Code in 2017. This is another area where the Arctic Council could further Arctic maritime governance. The Arctic Council’s history of getting members to come together to address communal issues related to environmental management and the prevention of major disasters has been predicated upon putting cooperation above national interest, and this has served as the foundation of the current Arctic regulatory regime, with several agreements and working groups focused on those concerns.

Conclusion

The Arctic Council is the best international body to begin addressing the complex issues surrounding maritime governance in the waterways of the Arctic region by developing and codifying communal responses to regional issues. In order for the Council to pursue such policies effectively it must have a community of members willing to work together and acknowledge the limitations imposed on the Council which have so far enabled its effectiveness for more than 20 years.

Ian Birdwell is a Ph.D. Student at Old Dominion University’s Graduate Program in International Studies. His research focuses on the exploration of the motivations behind the pursuit of Arctic security, how identity factors into the cultivation of regional habits, and the impacts of emerging trade routes on global power dynamics.

Featured Image: “North Pole” by Christopher Michael via Wikimedia Commons