Chokepoints and Littorals Topic Week

By Robert C. Rasmussen

“There are two types of Arctic problems – the imaginary and the real. Of the two, the imaginary are the most real.” –Vilhjalmur Stefansson

This century will be a transformative one, where rules taken for granted in the international system have begun to rapidly evolve. One of the most fundamental evolutions that is occurring is the transformation of physical geography from climate change and the resulting geopolitical implications. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the thawing Arctic. The ongoing transformation of the Arctic from an inaccessible frozen wasteland to an accessible and untapped reserve creates not only a new contested space, but will create new strategic chokepoints and littoral operating environments. The United States, in concert with its allies, will need to invest in the ability to access and secure this environment in order to maintain sovereignty and security in this new world.

The Changing Arctic

The emerging Arctic will be radically different than the one that has permeated human history. Historically, the Arctic is a frozen ocean surrounded by continental landmasses that have tundra and polar desert biomes along the coastal plains and islands.1 What keeps the Arctic frozen has been partially attributed to the planetary climate patterns that keeps cold air and weather at the poles, the season-long polar night,2 and the fact that snow and ice frozen for multiple years has an extremely high albedo – it reflects sunlight and heat.3

The difference now is that the planet is warming, and those changes are the most dramatic at the poles. This affects the Arctic Ocean and its littorals in many ways. The first notable effect is on sea ice. Sea ice expands and contracts seasonally, with a core of permanent sea ice, or multi-year ice, being augmented by younger ice, which is less than two years old. The multi-year sea ice is thicker and reflects more sunlight which makes it harder to melt. The younger sea ice is less thick and darker, making it easier to melt. The average extent of the permanent sea ice has been contracting continuously since 1978,4 and according to the International Panel on Climate Change, the Arctic will be ice-free or at least navigable in the summer season between the 2030s and the 2050s.5

The New Arctic Geography – Trade Routes, Chokepoints, and Inland Waterways

The reality of this environment is that it is increasingly warming and accessible. This produces rapid change which encourages various actors to compete for control of new sea lanes, prospecting for new resource reserves, and inevitably settlement of the Arctic by populations pushed to the north by climate change. These emerging issues will create the potential for conflicting sovereignty claims and access rights, as well as the assurance of those rights through the exercise of national power. There are four distinct geopolitical regions where fresh access, opportunity, and potential for conflict will occur. They are the Open Arctic Ocean, the North American Arctic Littoral environment, the Eurasian Arctic Littoral Environment, and the Arctic Seafloor.

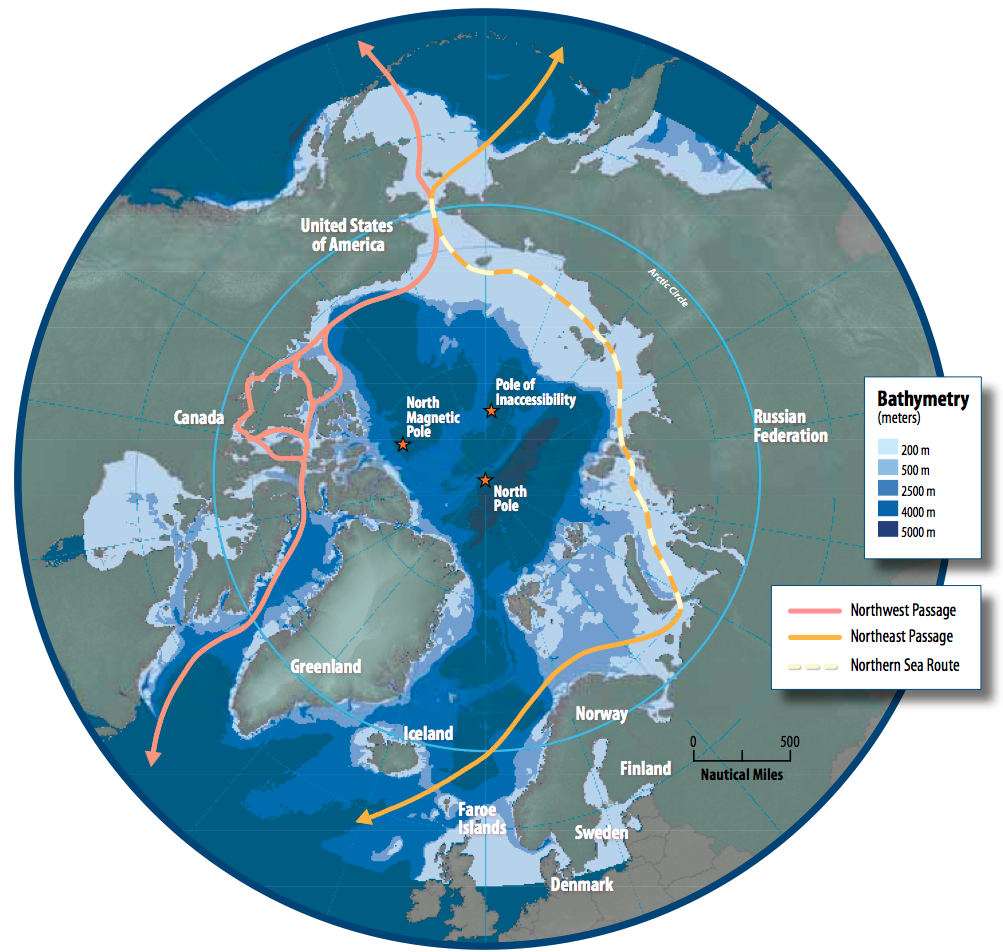

The Open Arctic Ocean has one critical potential sea lane and two major chokepoints. The major sea lane, which will not be open until the Arctic is at least seasonally ice free, is the Polar Sea Lane. This route spans from Europe to Asia and bisects the Arctic passing over the North Pole. The two major chokepoints here are the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) Gap – long famous as a planned line of defense against the Soviet Northern Fleet’s access to the Atlantic Ocean during the Cold War,6 and along the Bering Strait and Sea between Alaska (United States) and the Chukotka Peninsula (Russian Federation).7 The GIUK Gap sees a line cast between the islands of Greenland (Denmark), Iceland, the Faroe Islands (Denmark) and the Shetland and Orkney Islands (Scotland, United Kingdom),8 the Norway-Svalbard Gap, and the Svalbard-Greenland Gap serving as strategic chokepoints.9 Within the Bering Sea, both the Bering Strait and the Aleutian Islands can serve as chokepoints that can control access between the Arctic and the Pacific.10

The North American Littoral Environment has two distinct regions. The first is in the eastern portion, characterized by a large number of islands and seaways, which consist of the island of Greenland – an autonomous territory of Denmark, and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, largely contained in the federal territory of Nunavut, but also the Northwest Territories. The second, western portion, is one where coastal plains meet open ocean along Canada’s Yukon Territory, and the U.S. state of Alaska. The strategic trade route in this operating environment is the fabled Northwest Passage, which is rapidly becoming a reality with a seasonally ice-free or low-ice environment. The strategic chokepoints for this route start with the Labrador Sea and Barton Bay between the western coast of Greenland and the eastern/northern coast of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago’s largest island, Baffin Island.

The Eurasian Arctic Littoral is categorized as being largely coastal with the Eurasian mainland, but with a handful of Arctic Ocean islands which can serve as chokepoints, which are largely controlled by the Russian Federation, the exception being Svalbard – an archipelago controlled by Norway.

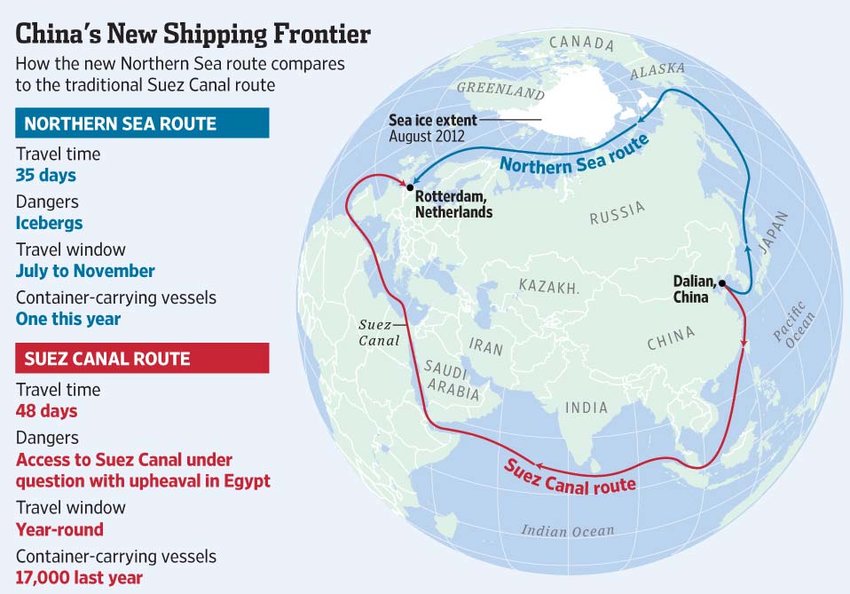

The strategic trade route in this region is the Northern Sea Route, which hugs the northern coast of Eurasia and provides a connection between Europe and Asia, and which is shorter than travel through the Suez Canal and Strait of Malacca. Chokepoints along this route include the Barents Sea gap between Norway and Svalbard, with Bear Island at the midpoint, and multiple chokepoints between Russian islands and archipelagos.

The Northern Sea Route is largely in operation already. A portion is open year-round to support domestic Russian commerce, and a remainder is open during the summer season which allows for trade between Europe and Asia. This route is open due to open waters and additional support from the Russian Federation’s fleet of 14 nuclear-powered icebreakers. China has also invested heavily into what they refer to as their Polar Silk Road, as part of their larger Belt and Road Initiative, including the construction of two more icebreakers. As the Arctic melts, this corridor will be able to accommodate significantly larger traffic flows. Such a shift will be fundamentally transformative to the Russian economy, allowing for Russia to achieve its centuries-old dream of holding blue water ports and subsequent access to global commerce.

An additional transformation to the Russian economy will be with inland waterways. The major inland waterways leading to the Arctic are the Ob’ River, the Yeinsei, and the Lena.

Access to blue water ports and commercial routes for these rivers will be fundamentally transformative to the Russian economy. Siberia is the most resource rich region within the Russian Federation, but extraction is oftentimes cost prohibitive, as the physical geography makes the construction of lengthy transportation corridors over land extremely difficult. Conversely, the implementation of large scale river transports moving from the heart of Russia to Arctic ports would dramatically lower the cost and risk of resource extraction, which will open up this traditional backwater to global commerce.11 With increasing commerce and infrastructure, this region will likely also see a population boom. Additionally, landlocked, but also resource-rich Kazakhstan and Mongolia will also have access to these inland waterways and Arctic ports, where this type of access would otherwise not exist.

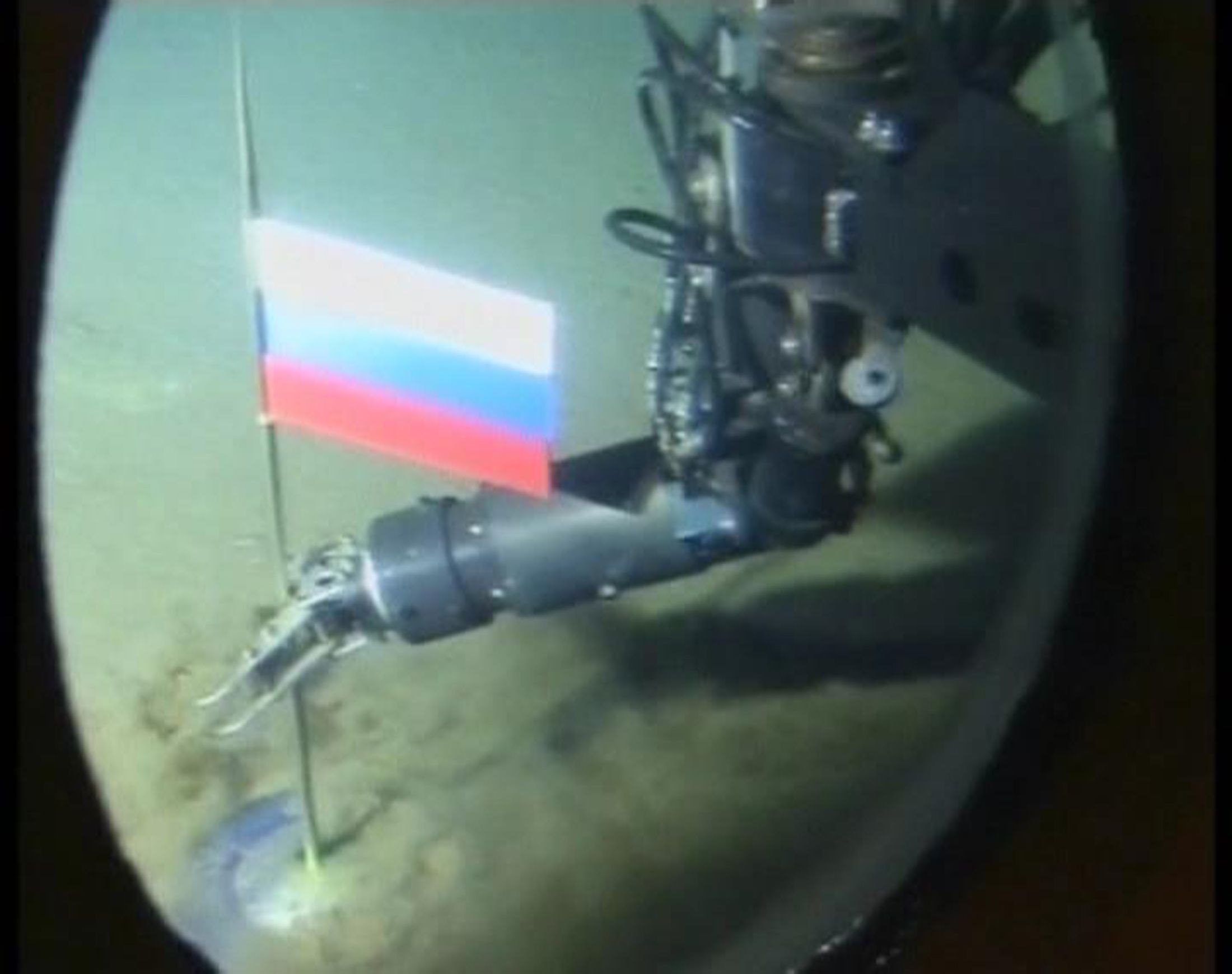

The last region in the Arctic will be the seafloor itself, with potential fishing rights, crude oil, and other mineral resources at stake. Fundamental to this region is that it has never properly been mapped, and mapping the seabed is instrumental for states with Arctic coastlines to be able to claim sovereignty and exclusive access to these resources. Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), territorial waters are limited to 12 nautical miles (nm), except for archipelagoes which are considered internal waterways, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) are limited to 200 nm for exploiting resources in the water such as seafood, and lastly rights to access mineral resources are limited by the continental shelf or the 200 nm EEZ, whichever is further.12 A lack of internationally recognized mapping of the Arctic seafloor has in the past and will in the future lead to conflicting claims, and possibly armed conflict itself.

One example for potentially conflicting claims was when the Russian Federation claimed sovereignty over the North Pole for mineral rights access in 2007. This claim was made based on the Russian assertion that the underwater Lomonosov Ridge, which runs across the Arctic seafloor between the East Siberian Shelf off the coast of the Russian Federation and the Lincoln Shelf off the coast of Greenland, was actually an extension of the East Siberian Shelf and thus subject to Russian sovereignty. Once this region is more accessible it will become a race to stake claims.

Policy Recommendations

The United States should continue with its longstanding policy of promoting clear international norms and standards when it comes to the emerging Arctic. The current risk is that peer competitors such as Russia and China will seek to exploit ambiguous norms, standards, or situations in order to make gains in economic or political power in the region. Bearing that in mind, the United States needs to be ready to leverage all tools of national power to protect U.S. interests. Part of that is building on and leveraging existing strengths.

The first most important policy the United States can pursue is by increasing funding for scientific research in the Arctic region, with a specific focus on international cooperation and recognition of results. Scientific research should focus on understanding the bathymetry (seafloor mapping) of the region that can be utilized as a diplomatic tool for international recognition of sovereignty claims as well as use of international waters. Promoting consensus prevents room for conflict.

The second policy the United States should pursue with its allies is full investment in the economic development of the Northwest Passage, bringing it into competition with the Northern Sea Route. This economic development would entail the economic development of ports in the Canadian arctic archipelago and development along the MacKenzie and Yukon River corridors. There would also be a need to invest in the construction of both a merchant and military icebreaker fleet, in order to facilitate and secure strategic trade routes. This development would provide an attractive alternative to the Northern Sea Route for the global shipping industry as the Arctic thaws.

The third policy the United States should pursue with its allies under the aegis of NATO is ensuring military superiority over the major strategic chokepoints in the Arctic. The primary focus would be on the GIUK Gap and the Aleutian Islands in particular, as routes that peer competitors Russia and China would have to rely upon converge at those two points. The GIUK, Norway-Svalbard, and Svalbard-Greenland Gaps being mostly open ocean would require a substantial naval blockade and air support to shut down traffic, similar to planning that defensive line during the Cold War, while the Aleutian Islands can rely on a chain of small outposts of anti-ship missiles with patrols preventing passage between the islands. The threat of force from NATO territory could serve as a deterrent from conflict, and as leverage in diplomatic negotiations in future conflicts that may arise. In this same vein, the United States should advocate for the establishment of a NATO Joint Forces Command – Arctic focused on consolidating NATO’s collective military power in the Arctic, coordinating the security of the Northwest Passage, and serving as a deterrent to conflict in the region.

Conclusion

The Arctic is evolving as the climate changes, and it is a change that will result in new opportunities for states to develop, as well as opportunities for regional conflict. Other actors have already taken action in the region, and the United States along with its allies cannot afford to be late to the game. The United States needs to rise to the challenge by promoting peaceful development through the promotion of international norms and standards, as well as ensuring the security of strategic trade and national sovereignty in coordination with allies.

Robert C. Rasmussen is a Foreign Affairs Specialist with the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration, and holds an MA in International Relations from Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, as well as a BA in International Relations and Geography from the SUNY College at Geneseo. He actively served in the New York Guard (State Defense Force) from 2010-2016, including participation in the response to Superstorm Sandy in 2012. He has long had an interest in the Arctic stemming from his childhood experiences while his family was posted to Fort Wainwright in Fairbanks, Alaska. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Nuclear Security Administration or the U.S. Department of Energy.

References

1. UC Museum of Planetology, “The World’s Biomes,” University of California, Berkeley,

https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/exhibits/biomes/index.php, Acc: 3 May 2020.

2. Leibowitz, Kari, “The Norwegian Town Where the Sun Doesn’t Rise,” The Atlantic, 1 July 2015,

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/07/the-norwegian-town-where-the-sun-doesnt-rise/396746/, Acc: 3 May 2020.

3. National Snow & Ice Data Center, “Thermodynamics: Albedo,” University of Colorado- Boulder,” 3 April 2020, https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/seaice/processes/albedo.html, Acc: 3 May 2020.

4. National Snow & Ice Data Center, “Arctic Sea Ice News & Analysis,” University of Colorado- Boulder, 3 May 2020, http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/, Acc: 3 May 2020.

5. American Geophysical Union, “Ice-Free Arctic Summers Could Happen on the Earlier Side of Predictions,” 27 February 2019, https://phys.org/news/2019-02-ice-free-arctic-summers-earlier-side.html, Acc: 3 May 2020.

6. Alison, George, “What are Norwegian F-35s Doing in Iceland?” UK Defence Journal, 3 March 2020, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/what-are-norwegian-f-35s-doing-in-iceland/, Acc: 3 May 2020.

7. Alaska Seas and Watersheds K-12 Program, SeaGrant Alaska, “Map of Aleutian Islands and Bering Sea,” University of Alaska, Fairbanks,

http://aswc.seagrant.uaf.edu/grade-4/investigation-1/map-of-aleutians.html, Acc: 3 May 2020.

8. Alison, George, “What are Norwegian F-35s Doing in Iceland?” UK Defence Journal, 3 March 2020, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/what-are-norwegian-f-35s-doing-in-iceland/, Acc: 3 May 2020.

9. National Geographic Society, National Geographic World Atlas- 7th Edition, Washington: National Geographic Society, 2000.

10. Alaska Seas and Watersheds K-12 Program, SeaGrant Alaska, “Map of Aleutian Islands and Bering Sea,” University of Alaska, Fairbanks,

http://aswc.seagrant.uaf.edu/grade-4/investigation-1/map-of-aleutians.html, Acc: 3 May 2020.

11. Vorotkinov, Vladislav, “Dredging Will Connect Siberia with the Northern Sea Route,” Dredging & Port Construction, 12 February 2019,

https://dredgingandports.com/news/2019/dredging-will-connect-siberia-with-the-northern-sea-route/, Acc: 3 May 2020.

12. Kumar, Abishek, “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,” Mariner Desk, 10 September 2018, https://www.marinerdesk.com/united-nations-convention-on-the-law-of-the-sea-unclos/, Acc: 3 May 2020.

Featured Image: Coast Guard members assigned to the U.S. Coast Guard Station Valdez head back to station after recovering hazardous radioactive material from a civilian vessel in the Port of Valdez, Alaska, during exercise Arctic Eagle 2018, Feb. 24, 2018. (U.S. Army National Guard photo by 2nd Lt. Marisa Lindsay)

The Arctic is indeed a critically important area that the US has largely abandoned. That needs to be fixed. It is important to keep some perspective on what might happen up there though. The NSR is indeed in operation now and is very important to the Russian economy especially for extractive industries, what we call destination shipping. It has been for some time and will be so in the future and likely to grow in importance. The Chinese investments there are driven more by strategic imperatives than economics. As a major route for transit shipping – large scale trade between Europe and Asia it is not useful and it is difficult to envision it ever being so. The NSR suffers from shallow water in places, more stringent ship construction standards, and unpredictable weather among other things. The largest ships reasonably expected to transit would be in the 3000 – 4000 TEU (number of containers carried) range while the traditional routes use ships in the 22,000 TEU range, so on a per unit of cargo basis, the NSR is vastly more expensive than the traditional routes plus suffers from schedule uncertainty, which in the container trade is a show stopper. Plus the vastly more expensive ship needed to meet ice standards that only has utility a few months a year makes it even worse. The beam of the icebreakers is also and issue – the ships being escorted can’t have a beam significantly larger than the icebreaker which also limits the size of the ship. So distance is not the only thing that matters, shorter does not mean cheaper. Our company (Maersk) made the trip with a small container ship, new construction feeder type ship intended to work in the Baltic once as an experiment and that was it. There is no intention to ever use the NSR for normal trade. The press usually gets this wrong too, like when a few years back there was much froth when the WSJ among other papers ran an article on the COSTCO ship Yong Sheng transiting claiming it was a containership transit and showing a picture of a big panamax ship when in fact the Yong Sheng is a small miltipurpose ship that had been trading the NSR for years. The NSR will never really be useful for transit trade between Asia and Europe on any scale, except maybe when Pittsburgh is a coastal city and the world in general is a very different place. Perspective is important when considering investments needed to deal with the changing Arctic.

Yes, the subject is a lot more complex than some think.

Increasing pollution adds to the matrix.