This piece originally published under the title of “Innovating the U.S.-Japan Alliance to Counter CCP Maritime Gray Zone Coercion: An Allied Coast Guard Approach,” in a monograph by the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies, at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. It is republished with permission.

By Jada Fraser

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) under General-Secretary Xi Jinping shows no signs of tamping down on its assertive campaign to secure revisionist territorial claims throughout the East and South China Seas, China’s Coast Guard’s (CCG) maritime gray zone activities present a particularly acute asymmetric challenge for the U.S.-Japan Alliance. This is because apart from the highly capable U.S. nuclear force and allied conventional military forces, in the realm of maritime gray zone coercion, the CCG faces no proportionate U.S. counterforce.1 On the other hand, Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) and Coast Guard continue to implement new technologies, upgrade logistics, and undergo reforms enabling Japanese maritime forces to more effectively track and respond to instances of gray zone coercion.

U.S. administrations have placed different levels of priority on determining the U.S. Coast Guard’s (USCG) role in countering maritime gray zone coercion in the Indo-Pacific and have yet to implement a coherent strategy. An analysis of recent reforms to Japan’s coast guard presents several models that the USCG can build off. Such an approach recognizes current U.S. resource limitations and accounts for how an important U.S. ally at the forefront of countering CCG gray zone activities has pursued its own reforms, even while under similar and additional constraints.

U.S. and Japanese maritime forces, especially both countries’ coast guards, must innovate allied approaches to more effectively counter gray zone efforts that undermine the rules-based international order. USCG reforms must center on expanding the force’s own role in countering CCG maritime gray zone coercion to be on par with that of the JCG. This will require that the USCG strengthen combined capabilities with JCG as well as expand interoperability with the U.S. Navy (USN). Modeling USCG operational and organization reforms on the JCG will enable an allied coast guard approach to countering PRC maritime gray zone coercion that bolsters the U.S.-Japan alliance’s overall deterrent effect in the Indo-Pacific.

Pride of Place: The Role of the CCG in China’s Maritime Gray Zone Activities

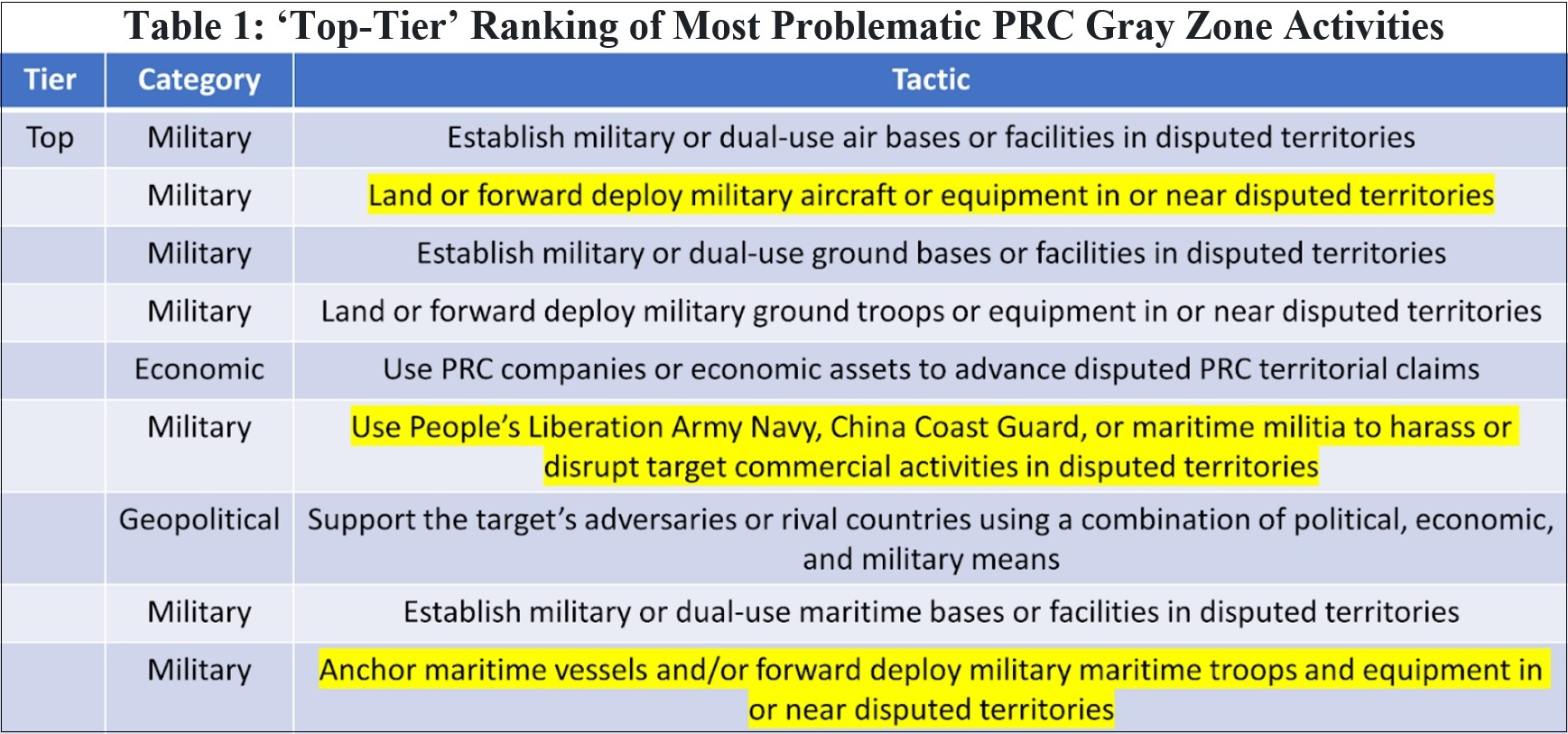

China’s increasing reliance on “gray zone activities”—defined here as means short of war but above the level of regular diplomatic efforts—exploits “asymmetric advantage[s] at a certain level or domain of conflict” to impose costs on or coerce capitulation from any state that takes actions inimical to the CCP’s interests.2 One area in which China holds considerable asymmetric advantages is in its utilization of non-military assets to perform military functions. The CCG figures prominently into the CCP’s toolkit for maritime gray zone activities, evidenced by the chain of command transfer in 2018 that reorganized the CCG to fall under the Central Military Commission (CMC).3 In a recent 2022 report on countering China’s gray zone coercion, RAND attempts to categorize different types of PRC military, political, economic, and information activities into three tiers from least to most problematic.4 Activities that do or can rely on the CCG claim three of the seven military gray zone activities identified within the most problematic ‘top tier.’

Unlike most coast guards around the world, the CCG is not separated from the military apparatus of the CCP as a law enforcement body and is in fact staffed with a large number of personnel from China’s Navy.5 The China Coast Guard Law passed in 2021 further muddied the waters on the rules of engagement with what is nominally a civilian entity, but clearly operates as a military force.6 These unique qualities prime the CCG to operate in the gray zone in a way that regional coast guards struggle to contend with.

As national sovereignty and territorial integrity reign supreme in the CCP’s conceptualization of security, sovereignty enforcement operations are at the core of the CCG’s role in maritime gray zone coercion.7 And indeed, because of the CCG’s assertive stance in enforcing CCP claims in the East and South China Seas, coast guards around the region have similarly had to take on a sovereignty-defending role– a function typically reserved for navies. On the other hand, the United States has not had to resort to using its coast guard to defend any of its own sovereignty claims (nor directly had to defend any of its allies’ claims thousands of miles away). In this view, compared to allied and partner countries’ direct experiences countering CCG gray zone activities, there has been a relative lack of pressure for USCG reform to improve maritime gray zone coercion responses.

Japan’s Coast Guard Reforms

Among the first countries to explicitly recognize the threat presented by China’s gray zone activities, Japan’s government has faced the extraordinary challenge of defending its territory from China’s sovereignty claims for decades.8 At the forefront of countering CCG maritime gray zone activities, Japan’s Coast Guard has had to grow both qualitatively and quantitatively. Between 2012 and 2020, the JCG fleet of large patrol vessels grew from 51 to 66, with an additional 6,000-ton vessel set to enter service in 2023 and another four recently announced by Prime Minister Kishida to join the fleet in the near-term.9 Patrol vessels have not only grown in size, but more are now capable of operating on the open ocean rather than only near Japan’s coastlines.11 Since 2012, the JCG budget and personnel have seen annual increases and the Kishida administration intends to more than double the budget by 2027.11

The nexus of CCG sovereignty operations focuses on the disputed Senkaku Islands. After facing multiple altercations in the area that could have easily spiraled into open armed conflict, in 2016 the JCG established a 12-ship Senkaku Territorial Waters Guard Unit and upgraded the Miyako Coast Guard Station to an office, doubling its patrol staff and adding eight new patrol vessels.12 In addition, in 2015 the JCG and JMSDF held a rare joint exercise, the first to be exclusively focused on gray zone activities.13 Two more of these exercises have been held since, one in 2021 and another this year, underscoring the accelerating pressure Japan is under to shore up its own domestic defense capabilities.

While reforms over the past decade all significantly enhanced JCG ability to respond to maritime gray zone activities, changes made in recent months and announcements for future reforms scheduled to take place over the next couple of years will exponentially improve JCG capacity to independently, jointly, and in a combined fashion with the USCG, respond to gray zone coercion. Importantly, these reforms seek to overcome remaining obstacles that have long been identified as impeding Japan’s ability to confront CCG maritime gray zone coercion most effectively.14

First, before the end of the fiscal year, the JCG and JMSDF plan to conduct the first-ever joint exercise to simulate an armed attack on the Senkakus.15 Such JMSDF-JCG cooperation is being made increasingly possible due to logistical and legal innovations and reforms. JCG intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities grew significantly with the recent commissioning of SeaGuardian UAVs in October 2022.16 Coinciding with this upgrade, JMSDF and JCG announced plans to transition to real-time data sharing from FY23.17 Moreover, soon after this announcement, the United States and Japan launched an intel-sharing unit that will “share, analyze and process information gathered from their assets, including drones and vessels,” in real-time. Considering future plans to streamline JCG-JMSDF intelligence-sharing, it is logical to assume that JCG intelligence will also be incorporated into the new U.S.-Japan intel unit as well.

Furthermore, it bears note that the SeaGuardian drones now being fielded by the JCG also have strike functions useful in anti-submarine warfare.18 This capability bears mentioning as JCG’s ability to take part in military actions has thus far been heavily constrained by Japan’s stringent legal framework which circumscribes the service as a purely civilian actor. While too soon to foretell any major legal reinterpretations of JCG scope in responding to armed conflicts, the GOJ recently reported plans to establish a framework for JCG-JMSDF cooperation.19

Japan’s newly released strategic documents also include a Joint Command Headquarters overseen by a joint commander, a position that will report directly to Japan’s defense minister.20 Japan’s general thrust toward greater jointness and interoperability portends opportunities for the JCG to be incorporated into such reforms. Indeed, the role of the JCG features prominently in Japan’s new strategic documents. In a significant organizational reform, the new National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy explicitly state that under situations of armed attack, JCG operational authority will move to the Minister of Defense, aligning with U.S.-style chain of command in contingency scenarios.21

Finally, with the Kishida administration’s plan to raise defense spending to 2 percent of GDP by FY27, budgetary calculations will now include expenditures on Japan’s Coast Guard as a defense budget line item. Unlike NATO countries, Japan has historically not classified JCG spending as a defense expenditure.22 While this reform may seem entirely bureaucratic in nature, Japan is the textbook example of how seemingly esoteric organizational reforms can have remarkable impacts on foreign and security policy.23 By including JCG spending in the defense budget, the government is opening itself up to criticism and pressure to strengthen the coast guard’s role in Japan’s national security and national defense strategies.

Taken together, these reforms will lead to significant improvements in interoperability both at the joint JCG-JMSDF level and more broadly within the scope of the U.S.-Japan alliance between the JCG and USCG and the JMSDF and USCG, perhaps even with all three forces working together trilaterally in the future. Yet the USCG still has far to go in order to capitalize on these potential areas of cooperation.

The USCG-JCG Partnership

Over the past half a decade, the USCG has gradually awakened to the challenges presented by the PRC’s gray zone activities in the Indo-Pacific. This realization is reflected in the 2020 tri-service strategy “Advantage at Sea” which sets the seapower services’ objectives over the next 10 years.24 The strategy emphasizes five objectives to effectively compete with China: integrated all-domain naval power; strengthened alliances and partnerships; operating more assertively to prevail in day-to-day competition; if conflict escalates, denying and defeating the enemy; and modernizing the force. The third objective explicitly highlights the Navy’s, Marines’, and Coast Guard’s role in countering maritime gray zone coercion (aka “day-to-day competition”). Moreover, the strategy document identifies the Coast Guard as the preferred maritime security partner for many nations vulnerable to this kind of coercion. Finally, it recognizes the Coast Guard as the singular force able to provide additional tools for crisis management through capabilities that can de-escalate maritime standoffs non-lethally. This is a role especially critical to managing conflict with the CCG.

Japan is home to one of only two overseas U.S. Coast Guard commands.25 Commander of the Coast Guard’s Pacific Area, Vice Adm. Michael McAllister, described the USCG-JCG relationship as “amongst its most valued partnerships.”26 And indeed, over recent months, the relationship has seen significant upgrades and could well be the USCG’s most important partnership. In May 2022, the two countries expanded formalized cooperation at what was dubbed a “historic document signing.”27 Building off an already 12-year-old partnership, Operation SAPPHIRE22 institutionalized standard operating procedures for combined operations, training and capacity building, and information sharing, with the aim of increasing USCG-JCG interactions over time. Taken together, these improvements will all greatly enhance USCG-JCG interoperability.

A few months into SAPPHIRE22, it appears quite clear what underlying motivations and goals fuel this mission. USCG and JCG have already conducted joint training and capacity-building activities with the Philippines Coast Guard twice since the memorandum of understanding was signed. JCG press releases of these activities explicitly link them to Japan’s strategy to realize a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.”28 USCG’s relationship with Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Forces has seen recent upgrades as well. Last year, the Japan-U.S. ACSA (Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement) was applied to the USCG for the first time to enable a JMSDF supply shop to replenish a USCG patrol vessel.29

These upgrades evidence the recognition of both countries that effectively competing with China will require updates to alliance cooperation at the technical, operational, and strategic levels. On the part of Japan, such recognition has played out in particularly pronounced ways. The government of Japan’s recent overhaul of the country’s strategic documents will likely produce historic evolutions in Japan’s defense orientation and security role within both the U.S.-Japan alliance and in the Indo-Pacific region more broadly. These changes are equally likely to create new possibilities for USCG cooperation with both the JCG and the JMSDF. But the burden will lie on the United States Coast Guard to implement reforms of its own in order to best take advantage of these new opportunities.

A Model for USCG Reforms

As stated earlier, there is increasing awareness in the White House and in the force itself that the U.S. Coast Guard’s role in the Indo-Pacific to counter maritime gray zone coercion needs to be strengthened. As Edgard Kagan, senior director for East Asia and Oceania on the National Security Council, recently made clear,

“The Coast Guard is an extraordinarily important tool, one that we are looking to see if there’s ways of expanding the presence and the level of engagement, because the issues that really matter to countries in the Pacific in many cases are much more aligned.”

There is much that could be done to broaden and strengthen this USCG role, specifically within the U.S.-Japan Alliance.

Model JMSDF-JCG Gray Zone Response Exercises

First, the USCG and the U.S. Navy should observe the gray zone exercises being conducted by the JCG and JMSDF and develop their own operational concepts for joint responses to gray zone activities. This would enhance the abilities of current and future USCG cutters home-ported in the Indo-Pacific to jointly respond with the Navy to gray zone activities throughout the region. But more importantly, it would enable both the Navy and the USCG to incorporate specifically targeted gray zone response activities as part of regular exercise and training deployments with regional partners, including Japan.

Strengthen Multilateral Coast Guard and Navy Cooperation

Second, beyond USCG training and capacity building deployments to the region (which are already strained by over-stretched resources), the U.S. Coast Guard should place a greater emphasis on coordinating to bring regional coast guards to Hawaii to train. One specific opportunity for this could be first to institutionalize regular USCG participation in multilateral naval exercises, such as RIMPAC, and then gradually expand to incorporate regional coast guard participation starting with Japan. RIMPAC has hosted USCG participation on the rare occasion, most recently last year. USCG participation in RIMPAC22 gave rise to several firsts. The coast guard participated in anti-submarine warfare exercises for the first time, and a national security cutter was the first ever to be equipped with the Link 16 tactical network system which enabled operational integration with the U.S. Navy.30 Traditionally, coast guard ships are not outfitted with the same network and communications platforms used by the military.31 Including both USCG and JCG in RIMPAC will enhance inter-service cooperation in addition to facilitating trust-building and cooperation between partnered and allied coast guards and navies. This will also add to overall regional deterrence by building important security linkages between partner and allied forces.

Enhance USCG-USN Interoperability to Expand Capacity for Combined Operations with Japan

Third and finally, modeling recent reforms to JCG-JMSDF interoperability, USCG platforms should be integrated with U.S. military network and communications platforms to enable more seamless real-time intelligence sharing and interoperability. To be best equipped for joint responses to gray zone escalation in the Indo-Pacific and to most effectively operate with Japanese forces, the Coast Guard and Navy cannot afford to maintain this current stove-piped system of communications.

Conclusion

Japan’s coast guard reforms and innovations offer several lessons for how the USCG can more effectively counter gray zone activities and best take advantage of the quickly growing partnership between the two forces as well as between the USCG and the JMSDF. By modeling USCG-USN gray zone exercises from JCG-JMSDF ones, the U.S.-Japan alliance can better prepare for joint responses to gray zone escalation in the region. Moreover, both the USCG and the Navy can incorporate these gray zone exercises and trainings into their own partnerships with regional coast guards. Institutionalizing USCG participation and including Japan’s Coast Guard in RIMPAC would maximize resource efficiency, enhance USCG-Navy interoperability, and strengthen regional coast guard and navy partnerships. Connecting USCG and Navy networks and communication platforms would enable both forces and the alliance to get the most out of the above reforms. Taken together, modeling USCG reforms on JCG operational and organizational innovations will enhance the U.S.-Japan alliance’s ability to counter CCP maritime gray zone coercion through an allied coast guard approach.

Jada Fraser is currently pursuing her Master’s in Asian Studies at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service where she serves as the Editor-in-Chief of the Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs. Jada has previously worked as a Policy Research Fellow for the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies at Johns Hopkins SAIS and as a Research Assistant with the Japan Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. She is a Pacific Forum Young Leader and a member of Pacific Forum’s inaugural cohort of the U.S.-Japan Next Generation Leaders initiative. Her work has been published by outlets such as Nikkei Asia, the Lowy Institute, and Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

References

1. Michael Green, Kathleen Hicks, Zack Cooper, John Schaus, and Jake Douglas, “Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia,” (CSIS, 2017).

2. Ibid.

3. Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform,” Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, April 2019, https://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/82/China%20SP%2014%20Final%20for%20Web.pdf?ver=2019-04-16-121756-937.

4. Bonny, Lin, Cristina L. Garafola, Bruce McClintock, Jonah Blank, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Karen Schwindt, Jennifer D. P. Moroney, Paul Orner, Dennis Borrman, Sarah W. Denton, and Jason Chambers, “Competition in the Gray Zone: Countering China’s Coercion Against U.S. Allies and Partners in the Indo-Pacific,” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA594-1.html.

5. Tsukasa Hadano, “China Packs Coast Guard with Navy Personnel,” Nikkei Asia, September 25, 2019; Ying Yu Lin, “Changes in China’s Coast Guard,” The Diplomat, January 30, 2019, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/China-packs-coast-guard-with-navy-personnel.

6. “People’s Republic of China Coast Guard Law” [“中华人民共和国海警法”], January 22, 2021, Article 47.

7. State Council Information Office, China’s National Defense in the New Era (2019), 3-15; Morris, Lyle J. (2017) “Blunt Defenders of Sovereignty – The Rise of Coast Guards in East and Southeast Asia,” Naval War College Review: Vol. 70 : No. 2 , Article 5, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol70/iss2/5.

8. Japan’s National Defense Program Guidelines has identified “gray-zone situations” as a core security challenge since FY2011. Ian Bowers and Swee Koh, Grey and White Hulls: An International Analysis of the Navy-Coastguard Nexus, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

9. Saito Katsuhisa, “The Senkaku Confrontation: Japan’s Coast Guard Faces Chinese ‘Patrol Ships,’” Nippon, April 26, 2021, https://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/d00698/; “MHI Launches 2nd 6000-Ton Patrol Vessel For Japanese Coast Guard,” Naval News, July 1, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/07/mhi-launches-2nd-6000-ton-patrol-vessel-for-japanese-coast-guard/; “Deployment status of large patrol vessels,” Japan Coast Guard Organization, https://www.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/e/organization/; “Japan to up coast guard budget 1.4-fold as Senkaku tensions rise,” Kyodo News, December 16, 2022, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/12/8b9426d368a9-japan-to-up-coast-guard-budget-14-fold-as-senkaku-tensions-rise.html.

10. Bonny Lin, et al., “Competition in the Gray Zone: Countering China’s Coercion Against U.S. Allies and Partners in the Indo-Pacific,” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA594-1.html.

11. “Japan to up coast guard budget 1.4-fold as Senkaku tensions rise,” Kyodo News, December 16, 2022, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/12/8b9426d368a9-japan-to-up-coast-guard-budget-14-fold-as-senkaku-tensions-rise.html.

12. Ibid.

13. Céline Pajon, “Japan’s Coast Guard and Maritime Self-Defense Force: Cooperation among Siblings,” National Bureau of Asian Research, December 1, 2016, https://www.nbr.org/publication/japans-coast-guard-and-maritime-self-defense-force-cooperation-among-siblings/.

14. Scott W. Harold, et al., “The U.S.-Japan Alliance and Deterring Gray Zone Coercion in the Maritime, Cyber, and Space Domains,” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017, https://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CF379.html.

Céline Pajon, “Japan’s Coast Guard and Maritime Self-Defense Force in the East China Sea: Can a Black-and White System Adapt to a Gray-Zone Reality?” Asia Policy 23 (January 2017), 129; Ian Bowers and Swee Koh, Grey and White Hulls: An International Analysis of the Navy-Coastguard Nexus, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

15. “MSDF, JCG to hold drill simulating armed attack on Senkakus,” Yomiuri Shimbun, November 9, 2022, https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/politics/defense-security/20221109-69715/.

16. Mike Yeo, “Japan starts operations with SeaGuardian drone, receives two Hawkeyes,” Defense News, October 20, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/air/2022/10/20/japan-starts-operations-with-seaguardian-drone-receives-two-hawkeyes/.

17. “Japan Coast Guard to share real-time surveillance info with navy,” Kyodo News, November 7, 2022, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/11/0c2f4315e9ab-corrected-japan-coast-guard-to-share-real-time-surveillance-info-with-navy.html.

18. “Japan puts modern drone into operation to enhance maritime security,” Radio Free Asia, October 26, 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/southchinasea/japan-drones-10262022031230.html.

19. “MSDF, JCG to hold drill simulating armed attack on Senkakus,” Yomiuri Shimbun, November 9, 2022, https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/politics/defense-security/20221109-69715/.

20. “Japan plans new joint command to manage armed forces, Nikkei reports,” Reuters, October 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/japan-plans-new-joint-command-manage-armed-forces-nikkei-2022-10-29/.

21. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “National Security Strategy of Japan,” December 16, 2022, https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/siryou/221216anzenhoshou/nss-e.pdf.

22. “Japan mulls adding coast guard costs to defense budget,” Stars and Stripes, September 10, 2022, https://www.stripes.com/theaters/asia_pacific/2022-09-10/japan-mulls-adding-coast-guard-costs-defense-budget-7283139.html.

23. Michael J. Green, Line of Advantage: Japan’s Grand Strategy in the Era of Abe Shinzo, New York: Columbia University Press, 2022, pp. 183-184.

24. “Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power,” Department of Defense, December 2020, https://worldcat.org/title/1230505167.

25. Christopher Woody, “On the front lines against China, the US Coast Guard is taking on missions the US Navy can’t do,” Business Insider, January 11, 2022, https://www.businessinsider.com/in-china-competition-us-coast-guard-does-unique-missions-2022-1.

26. Dzirhan Mahadzir, ” U.S. Coast Guard Continues to Expand Presence in the Western Pacific,” USNI News, September 3, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/09/03/u-s-coast-guard-continues-to-expand-pressence-in-the-western-pacific.

27. Fatima Bahtić, “US, Japan coast guards expand cooperation, establish new operation Sapphire,” Naval Today, May 20, 2022, https://www.navaltoday.com/2022/05/20/us-japan-coast-guards-expand-cooperation-establish-new-operation-sapphire/.

28. “SAPPHIRE22 US-Japan Joint Training for the Philippine Coast Guard (Summary of results) – Promoting the joint USCG-JCG efforts toward the realization of a Free & Open Indo-Pacific,” Japan Coast Guard, November 7, 2022, https://www.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/e/topics_archive/article3886.html.

29. “JS OUMI conducted bilateral exercise with U.S. Coast Guard,” Japan Ministry of Defense, August 26, 2021, https://www.mod.go.jp/msdf/sf/english/news/08/0831.html.

30. Sean Carberry, “SPECIAL REPORT: Coast Guard Packs a Punch at RIMPAC,” National Defense Magazine, August 17, 2022, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2022/8/17/coast-guard-packs-a-punch-at-rimpac.

31. Ibid.

Featured Image: Ships from the U.S. Coast Guard and Japan Coast Guard conducted exercises near the Ogasawara Islands of Japan, Feb. 21, 2021. (U.S. Coast Guard photo courtesy of the Coast Guard Cutter Kimball/Released)

The author seems to know a lot about the Japan Coast Guard, but not a lot about the US Coast Guard and its relationship with the US Navy. Suggest a review of the National Fleet Plan.

https://media.defense.gov/2020/May/18/2002302026/-1/-1/1/FLEET_PLAN_FINAL.PDF