The Pentagon’s analogy of China and Falkland-Style wars does not mean that it is yet meeting all such necessary criteria. Instead, the analogy tells us about the PLAN’s present and future rank in the hierarchy of navies. Although Europe is in decline, Europeans should not bury their heads in the sand. There are still useful efforts that can be done.

Does the analogy apply?

The Pentagon’s latest Annual Report to Congress says that China has increasing emerging expeditionary naval interests. The Report emphasizes China seeks the capabilities to fight a Falklands-Style wars:

“The PLA Navy’s goal over the coming decades is to become a stronger regional force that is able to project power across the globe for high-intensity operations over a period of several months, similar to the United Kingdom’s deployment to the South Atlantic to retake the Falkland Islands in the early 1980s. However, logistics and intelligence support remain key obstacles, particularly in the Indian Ocean.” (DoD 2013, p. 38)

One can question whether the historic analogy between the UK in 1982 and China after 2013 does really apply. China has no overseas territories like Britain’s Falklands, Diego Garcia, and Pitcairn; or France’s Martinique, Reunion, and Polynesia. Obviously, the geography in the North and South Atlantic is very different from the Indo-Pacific theater. And, being under sequester-siege, one can ask if the U.S. Admirals are over-hyping China’s rise to defend their budgets. On the other hand, one can be sure that the Pentagon’s officers are aware of what they are talking about when they use analogies. Moreover, when talking about expeditionary campaigns of navies underneath the U.S.’ full-scale war level, other cases are hard to find.

What “Falklands-Style” is not about:

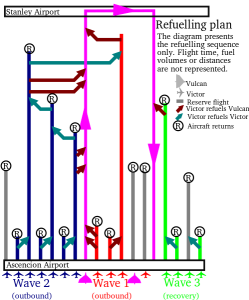

Britain’s major obstacle in 1982 was that its “closest” airbase was on the tiny island Ascension 6,300 kilometers from the Falklands. Thus the Falklands-style does not apply to scenarios like Taiwan or the East and South China Sea; China’s military facilities are right next to the theater. Any Chinese campaign in these areas would more be more like NATO’s Libya campaign than the Falklands due to PLAAF bases close to the battlefield. In 1982, Britain conducted some symbolic air raids with Avro Vulcan bombers on Port Stanley’s airfield, however only made possible by a very complex chain of aerial refueling. Britain’s success or failure was dependent on the two carriers HMS Hermes and HMS Invincible. If one or both of them would have been sunk, Britain would have lost, because the Royal Navy could only succeed due to the air power delivered by the seaborne Harriers.

“Falklands-Style” means a carrier-centric operation far away from the homeland. Carriers are an inevitable necessity for expeditionary campaigns due to the need for air superiority. Moreover, such a “Falklands-Style” operation would include some, but not a lot of support from overseas bases and be out of reach of homeland airbases, as Port Stanley was 11,000 kilometers away from London. A “Falklands-Style” campaign’s ultimate operational target is to bring boots on the ground by amphibious landings. Politically and strategically, the aim is to achieve military superiority over another state in certain geographical areas, but not over a whole country – that would be “Iraq-Style.” In addition, Falklands-Style does not apply to non-state actors. They lack the ability to deliver significant, nearly equal air and sea power in the theater as the Argentinians did.

China’s “Falklands-Style” Capabilities

Applied to the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), geographically “Falklands-Style” means an operation beyond the Second Island Chain or “West of Malacca”. However, China does not meet the carrier criteria and it is unlikely to do so before 2020. Moreover, overseas bases are planned, but their operational worth cannot be taken for granted. Gwadar in Pakistan is the PLAN’s only project which can be taken seriously right now. However, in any action, Gwadar would have to be supplied by complex air logistics (the forthcoming Y-20). Railroads or even useable roads from Pakistan to China just don’t exist.

Beside the two carriers with their 48 Harriers, the Royal Navy’s Task Force included two LPDs, eight destroyers, 15 frigates, five nuclear subs (SSN), one conventional sub and dozens of support vessels. In total, Britain sent over a hundred ships. Many of the supply ships were requisitioned civilian vessels. China’s fleet in 2013 includes one carrier (Liaoning, not yet operational), three LPDs, 14 destroyers, 62 frigates, four SSBNs, five SSNs, 55 conventional subs, and 205 logistic and support ships (IISS 2013: 289-290). Thus, in all cases except the carriers China’s numbers meet or exceed Britain’s Task Force.

Moreover, China’s is the world’s largest shipbuilder. While hulls for sophisticated military vessels like carriers may still be challenge, China can easily mass-produce simple hulls for transport and supply ships or confiscate ships present in Chinese ports, as the UK did. China is working on further tanker and supply ships to support expeditionary operation. Other observers like Information Dissemination, one of best-informed blogs, note that China is already able to build sophisticated ships like LHDs:

“Last year, we were introduced to a LHD design that China was offering for export. A couple of months ago, we’ve seen this LHD design displayed for export to Turkey and also at Abu Dhabi. This mysterious design is said to be 211 m long, 32.6 m in beam and 26.8 m high for a displacement of 20,000 to 22,000 ton. It’s a little wider than Type 071 and has a flat top, so it can hold 8 helicopters with the hangar space for 4. This is an increase over Type 071, but I would imagine the first Chinese LHD (let’s call it Type 081) to be much larger than this (30,000 to 40,000 in displacement) and able to hold carry more helicopters and armored vehicles. I personally think PLAN has studied USMC long enough that it would also want the LHD to be able to support STOVL fighter jet. Such a ship would be much more complex than Type 071, but is well within the technical capabilities of Chinese shipyards.”

In addition, “Falklands-Style” campaigns depend on a capable nuclear-powered submarine force. Argentina withdrew its surface fleet after the cruiser Belgrano was sunk by the SSN HMS Conqueror, which provided the Royal Navy the freedom of action for amphibious landings. If you want your subs to go to places, you need nuclear power. Recently the PLAN has demonstrated that her SSNs are able to reach the Indian Ocean. In contrast to the Royal Air Force in 1982, China is incapable of undertaking long-range airstrikes in order to support expeditionary operations. Its so-called Xian H-6 “bombers” (combat radius 970nm) are a further-developed Soviet Tupolev TU-16 aircraft. These are supported by very few aerial refueling capabilities and have no operational experience at all in conducting long-range airstrikes. Operational experience matters, as can be seen in the discussions about the possibility of an Israeli strike against Iran.

Finally, “Falklands-Style” wars and expeditionary operations also require a lot of operational experience. Officers and crews need to be able to deal with and adjust to friction immediately. The service (wo)men must have a pragmatic problem-solving attitude because rapid help from home is unavailable. The Royal Navy had such a capacity, gained over decades of experience leading to 1982. China today is working from slight operational experience developed by anti-piracy operations, regular drills, and friendly ports visits, but is far away from the human skills navies like the U.S. or British posses.

What the Falklands Analogy Really Tells Us

Discussing where Chinese “Falkland-Style” wars could take place is just like reading tea leaves. Will China raid Diego Garcia or Darwin in case of a fight against the U.S.? Could Pacific Island states Sri Lanka, the Seychelles, or Mauritius somehow become objectives of PLAN amphibious invasions? Will China strike Persian Gulf or East African countries in order to secure their resources? Nobody can know for certain. We will see when we (don’t) get there.

What the analogy really tells us is where China is going in the hierarchy of navies. Geoffrey Till emphasized that the most sophisticated attempt ever undertaken at classifying navies was done by Eric Grove (Till 2013: 114). In 1990, Grove classified navies from a Rank of 9, “Token”, to a Rank of 1, “Major Global Force Projection – Complete” (Grove 1990: 237-240). Of course, Rank 1, until present, was only achieved by the U.S. Rank 2 Major Global Force Projection – Partial was achieved just one time by the Soviets during the 1980s until 1991/92, but never again by any country.

Relevant for the given case are Rank 3, “Medium Global Force Projection”, and Rank 4, “Medium Regional Force Projection.” Rank 3 means that a navy posses at least one carrier, amphibious capabilities, SSBN, SSN and a larger number of surface warships like destroyers and frigates. According to Grove, a Medium Global Force Projection Navy would “be capable of conducting one major ‘out of area operation and (…) would be capable of engaging in high-level naval operations in closer ocean areas” (Grove 1990: 238). Thus, Britain in 1982 has to be understood as a Rank 3 case.

Grove considered the PLAN to be a Rank 4 Medium Regional Force Projection case (Grove 1990: 238). With no carriers or expeditionary amphibious capabilities, the PLAN was able by its submarines and surface warships to exercise maritime power in the West Pacific, but not beyond.

The Pentagon’s Annual Report is talking about China “becom[ing] a stronger regional force that is able to project power across the globe for high-intensity operations over a period of several months” (p. 38). Hence, the Pentagon’s analysis matches exactly with Grove’s criteria (surprise, surprise?). Most remarkable is that even in 1990 Grove foresaw that China could become a candidate for Rank 3 “in the medium- to long-term” and could even move “into Rank 2, but not for several decades” (Grove 1990: 238). Now – 23 years after Grove’s excellent classification – China is on the way to move(sic) from Rank 4 to 3. However, it is not there yet. The criteria for operational carriers is not fulfilled. Moreover, the main reason why I personally would not rank China a 3 is that its military has had no combat experience since 1979. Therefore, what the Pentagon’s analogy and Grove’s classification really tell us, is how hard it is to climb up the Ranks in the hierarchy of navies.

How Europe Should React

China’s expeditionary ambitions are more westward looking than eastwards. As the Report outlines, Beijing’s areas of concern are the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, and even the Mediterranean. The Times of India, for example, reported something similar:

“(…), and the Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean is expected to grow. David Shinn, a former U.S. ambassador in Africa, expects China’s navy to make more frequent visits to port cities across the Indian Ocean – in South Asia, the southern Middle East and on the east coast of Africa – within the next 10 years and to expand its reach to North African ports on the Mediterranean Sea.”

Thus, Europeans should pay as much or even more attention than the U.S. to what the Chinese are doing. Given that the U.S. really continues to retreat from the Middle East, the Western Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf will become areas of major concern in particular for Europe.

Instead of living in the world of political correctness and talk about utopian ideas, said German EU-Commissioner Günter Oettinger in May, many Eurocrats from the Brussels Bubble must abandon their geostrategic blindness. Except for themselves, in real life nobody outside Europe cares that the EU is promoting human rights, environmental protection, and gender equality. Europe will never become an international actor taken seriously on other continents as long as geopolitical, geostrategic, and strategic thinking only happens in Paris and London. Therefore, it is not a surprise, that China’s media scoffs about European decline and tells the Europeans to shut up.

However, there is no need for unconditional surrender. Many useful things can be done today. Maritime cooperation between NATO and China has already started and seems to work. Thus, this program should be continued and extended to build mutual trust. Moreover, Chinese and European interests for safe and secure sealanes in the Indian Ocean are the same. Some kind of permanent maritime security cooperation, maybe even including India, would absolutely make sense.

To implement this, Europeans must in composite preserve a Rank 3 status as a “Medium Global Force Projection Navy”; either uni-/bilaterally by France and Britain or by a broader European coalition. If Europe would be unable to deliver significant maritime power eye to eye with China, leaders in Beijing with command over a Rank 3 navy (maybe moving towards Rank 2) would tell the Europeans to simmer down when Brussels calls for a “political solution” or “multilateral dialogue” about the Indian Ocean.

Britain and France will continue their fight not to drop down to Rank 4. The UK’s coming Queen-Elizabeth-Carriers are definitely a boost to British (and European) power-projection capabilities. However, the economic and financial situation raises large questions as to whether both countries will be able to sustain their levels of defense spending, especially France. While London has, Paris has not undertaken any serious cuts yet. Needless to say that France’s terrifying financial and economic situation will bring the question of cutting defense spending on the table. The most likely scenario is that Britain and France will continue to go together, whenever they cannot go alone. However, due to harsh cuts in the French military budget, the time could come, where Anglo-French cooperation will not be enough anymore. Without any U.S. military bailout in sight, a pivotal indicator for Europe’s future as a maritime power is whether countries like the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, and in particular Germany are more willing to pool and share substantially and to go to places together.

By Felix Seidler, Institute for Security Policy, University of Kiel, Germany / German security affairs writer. This article appeared in original form at his website, Seidlers Sicherheitspolitik.

Bibliography

Grove, Eric 1990: The Future of Seapower. Annapolis.

IISS 2013: The Military Balance. London.

Till, Geoffrey 2013: Seapower. London.

Rather than Falklands style perhaps it is more like the many incursions into third world countries that have been done by the US and European Navies to protect their interests and their citizens.

The effort to remove thousands of Chinese nationals from Libya was wake up call that also earned the Chinese military high marks at home, but it probably also brought up the specter of a similar operation done under fire.

Agree. Britain’s intervention in Sierra Leone in 2000 can be an analogy.

Felix, you’re doing well at dissecting the problem of historic analogy. In general, I would always say that taking historical examples 1:1 is a problematic approach, for history – as we know – does not repeat itself. At the same time, the Falkland War example is instructive for the question just how a force from 1,000s of miles away would re-take/liberate an island (or territory similiar to that) that has been taken over by a competitor state. In my view, the analogy is not about if and how much Wester Pacific islands resemble the British outpost in the South Atlantic, and how much of 1982 will be relevant in the year 20… (if at all); rather, it is important to note just how a potential grave escalation (invasion, take-over, breach of international law, etc.) could and should be contained or repelled. This is the back-story to what naval strategists and political planners will have to keep in mind, for the Falkland War does remain as one of the last state-on-state naval war examples. (cross-posted comment at Seidlers Sicherheitspolitik and offiziere.ch)