Last week an article came out about state-sponsored hacking that had nothing to do Edward Snowden or the NSA. Bloomberg News detailed the ongoing hacking of U.S. defense contractor QinetiQ. Two paragraphs in the piece particularly struck me:

“The [China-based] spies also took an interest in engineers working on an innovative maintenance program for the Army’s combat helicopter fleet. They targeted at least 17 people working on what’s known as Condition Based Maintenance, which uses on-board sensors to collect data on Apache and Blackhawk helicopters deployed around the world, according to experts familiar with the program.

The CBM databases contain highly sensitive information including the aircrafts’ individual PIN numbers, and could have provided the hackers with a view of the deployment, performance, flight hours, durability and other critical information of every U.S. combat helicopter from Alaska to Afghanistan, according to Abdel Bayoumi, who heads the Condition Based Maintenance Center at the University of South Carolina.”

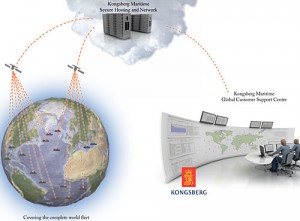

While it’s unclear whether the hackers succeeded in accessing or exploiting the data, it is clear that they saw the information as valuable. And rightly so – systems such as condition based maintenance, remote diagnostics, and remote C2 systems are designed to reduce the workload burden on front-line “warfighters”, or the logistics burden on their platforms, by shifting the location of the work to be done elsewhere. This can also facilitate the use off-site processing power for more in-depth analysis of historical data sets and trends for such things as predicting part failures. The Army is not alone in pursuing CBM. The U.S. Navy has integrated CBM into its Arleigh Burke-class DDG engineering main spaces, meaning “ship and shore engineers have real maintenance data available, in real time, at their fingertips.”

However, the very information that enables this arrangement and the benefits it brings also creates risk. Every data link or information conduit created for the benefit of an operator means a point of vulnerability that can be targeted, and potentially exploited – whether revealing or corrupting potentially crucial information. This applies not only for CBM, but more dramatically for the C2 circuits for unmanned systems. I’m by no means the first to point out that CBM, et al, means tempting targets. UAV hacking has garnered a great deal of attention in the past year, but the Bloomberg article confirms an active interest exists in hijacking the enabling access of lower profile access points.

This raises several questions for CBM and remote diagnostics, not least of which is “is it worth it?” At what point does the benefit derived from the remote access become outweighed by the risks of that access being compromised? Given the sophistication of adversary hacking, should planners operate from the starting assumption that the data will be exploited and limit the extent of its use to non-critical systems? If operating under this assumption, should “cyber defense” attempts to protect this information be kept to a minimum so as not to incur unnecessary additional costs? Or should the resources be devoted to make the access as secure as the C2 systems allowing pilots to fly drones in Afghanistan from Nevada?

Scott is a former active duty U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer, and the former editor of Surface Warfare magazine. He now serves as an officer in the Navy Reserve and civilian writer/editor at the Pentagon. Scott is a graduate of Georgetown University and the U.S. Naval War College.

Note: The views expressed above are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their governments, militaries, or the Center for International Maritime Security.