The following was originally published by the Leidos Chair of Future Warfare Studies of the Naval War College under the title Crafting Naval Strategy: Observations and Recommendations for the Development of Future Strategies. Read it in its original form here. It is republished here with permission and several excerpts will be featured.

By Bruce Stubbs

Observation 33

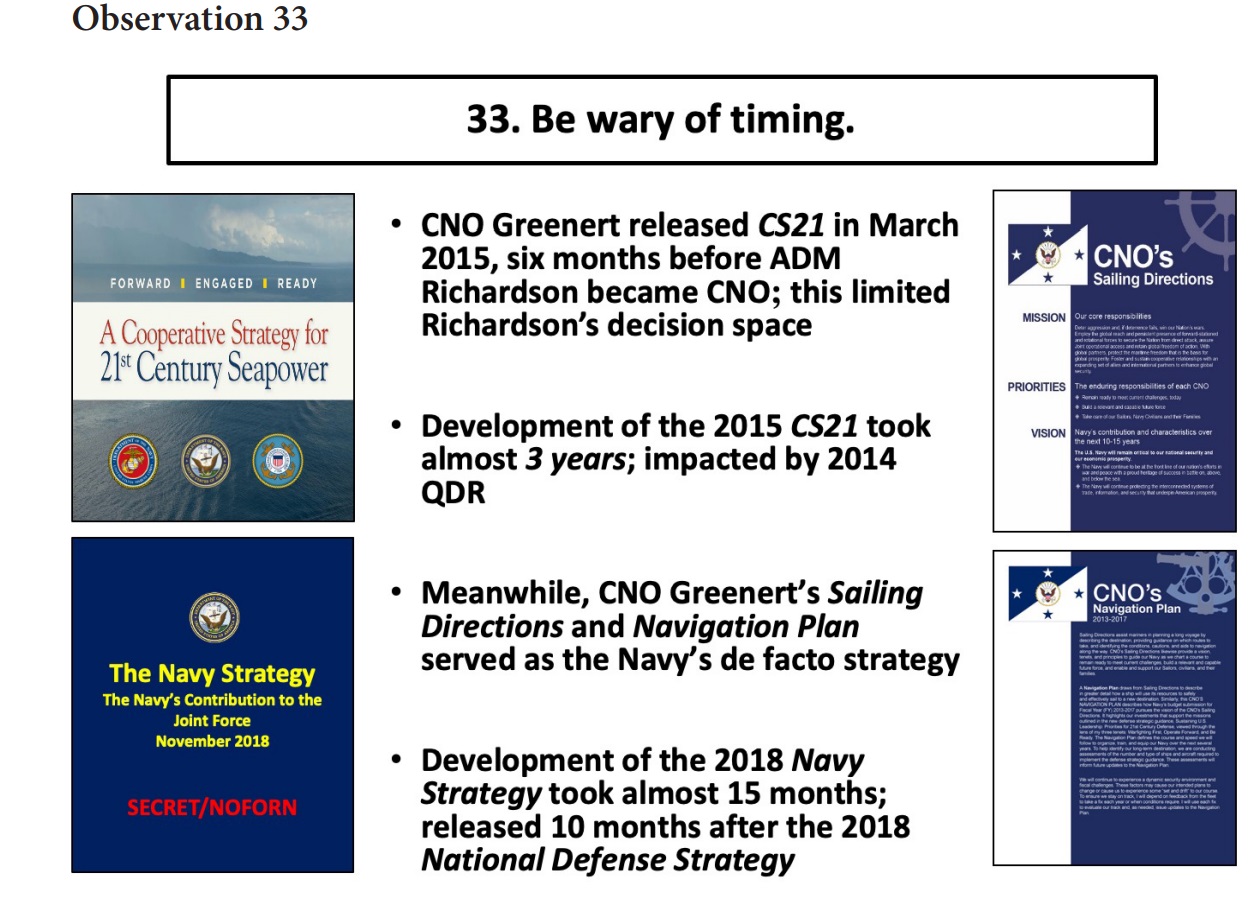

Obviously, the crafting of strategy takes time. What may not be obvious is that the timing of issuing a strategy plays a major role in its overall effectiveness, let alone its effective dissemination. Similar to policies issued in the final months of a lame-duck presidency, those strategy documents issued shortly before a change of Navy or DoD leadership rarely have significant impact or lasting effect.

Strategy documents ultimately reflect the desired policies of the chief strategist (the CNO); thus their implementation is dependent on the tenure of the strategist, or on the willingness of his successor to maintain the same strategy without significant revision. In a competitive environment in which hyperbole-laced debates over resources take place, the thirst for a “new” strategy with new, “innovative” terminology and arguments is always present. Leaders feel pressure to sign off on their own strategy documents. This creates a churn in which strategies appear credible only as long as the chief strategist/leader remains in that position. Strategies issued early in the leader’s tenure have a chance to gain effect, whereas those issued late in the tour indeed are viewed as lame ducks.

In recent years, continuity has become very artificial. Instead of attempting to replace an existing official strategy document, SECNAVs and CNOs have issued guidance papers and directives that reinterpret or supersede some part of the existing strategy.

Often this has been done for the sake of speed and to avoid a laborious crafting of strategy. Sometimes, however, it is done to avoid public debate about or external involvement in any obvious shift in Navy strategy.

Meanwhile, new strategies from higher authorities may or may not be issued on any firm schedule. Such schedules may exist, particularly as concerns joint documents, but often they are overtaken by events. Congress has put in place (legal) time requirements for the issuance of the president’s National Security Strategy, but recent administrations have ignored these time requirements without consequence. Presumably, Navy strategies should incorporate all the guidance from the NSS, the SECDEF’s National Defense Strategy, and the CJCS’s National Military Strategy, but rarely do they align in sequence or terminology. Crafters of strategy must be wary of timing, but there are no hard-and-fast answers except that any strategy issued late in a CNO’s term is unlikely to have any significant effect.

Observation 35

Most defense debates are not about strategy, but instead about the adoption of new capabilities—of which emerging technologies have become a driving factor. This has given many of the debaters the impression that the emergence of new technologies automatically overturns existing strategies and that technological development and acquisition is an effective strategy in itself. This impression violates the very definition and theory of strategy, because the conflation of technology and capabilities with strategy ensures that the ends are defined by the means. As the old saying goes, “To a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Driving a nail into the wrong place at the wrong time simply because the hammer exists—even if it is the most technologically advanced hammer ever conceived—is not good strategy. In fact, it is not strategy at all.

Observation 36

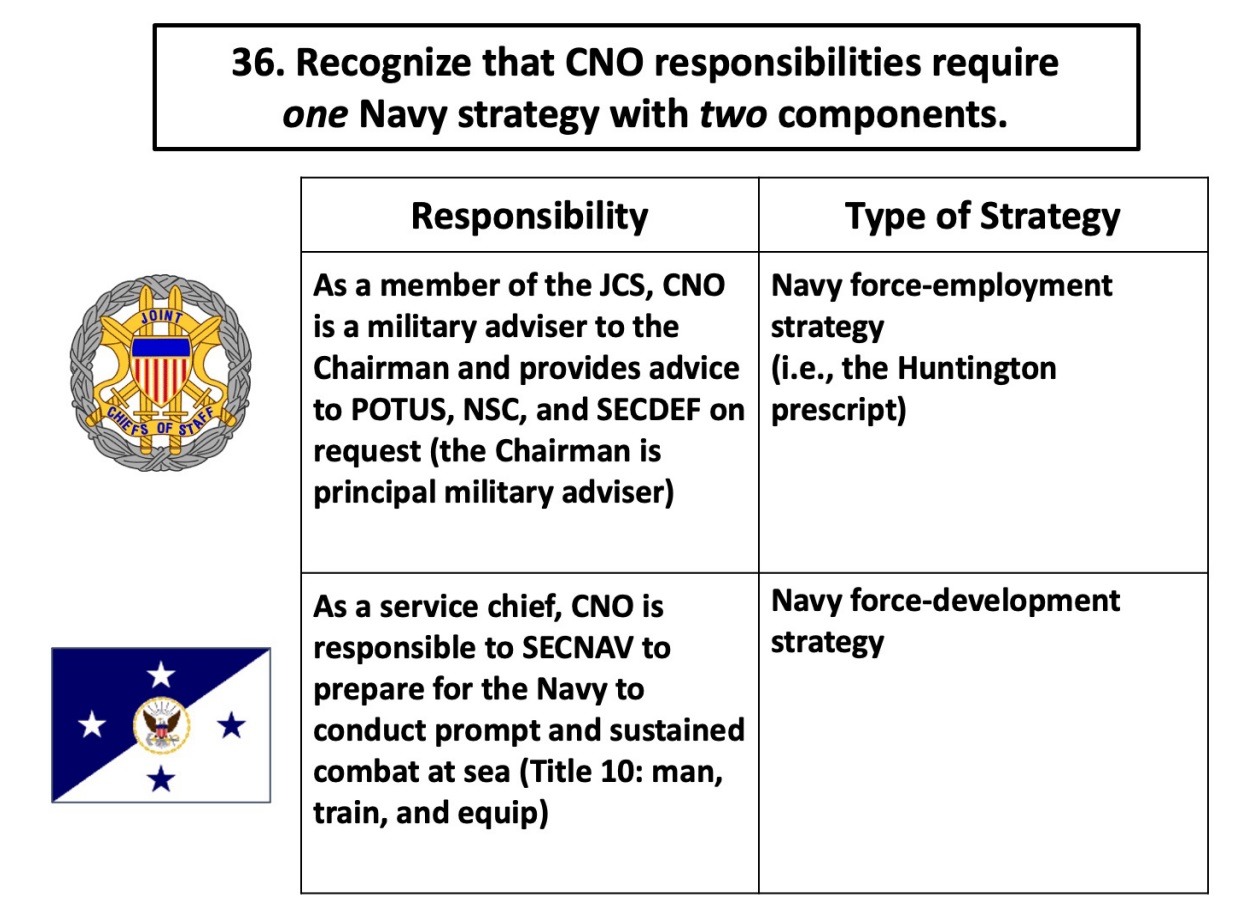

The CJCS is the principal military adviser to the president, SECDEF, and NSC. All Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) members have a responsibility to provide advice or opinions, when requested or on their own initiative, via the CJCS, to the president, SECDEF, and NSC. Therefore, in addition to the CNO’s Title 10 responsibility to develop the Navy, he has a responsibility to describe to the JCS how the Navy will be employed. This requires two distinct strategies, one to develop the force and the other to employ the force. The two strategies require different components.

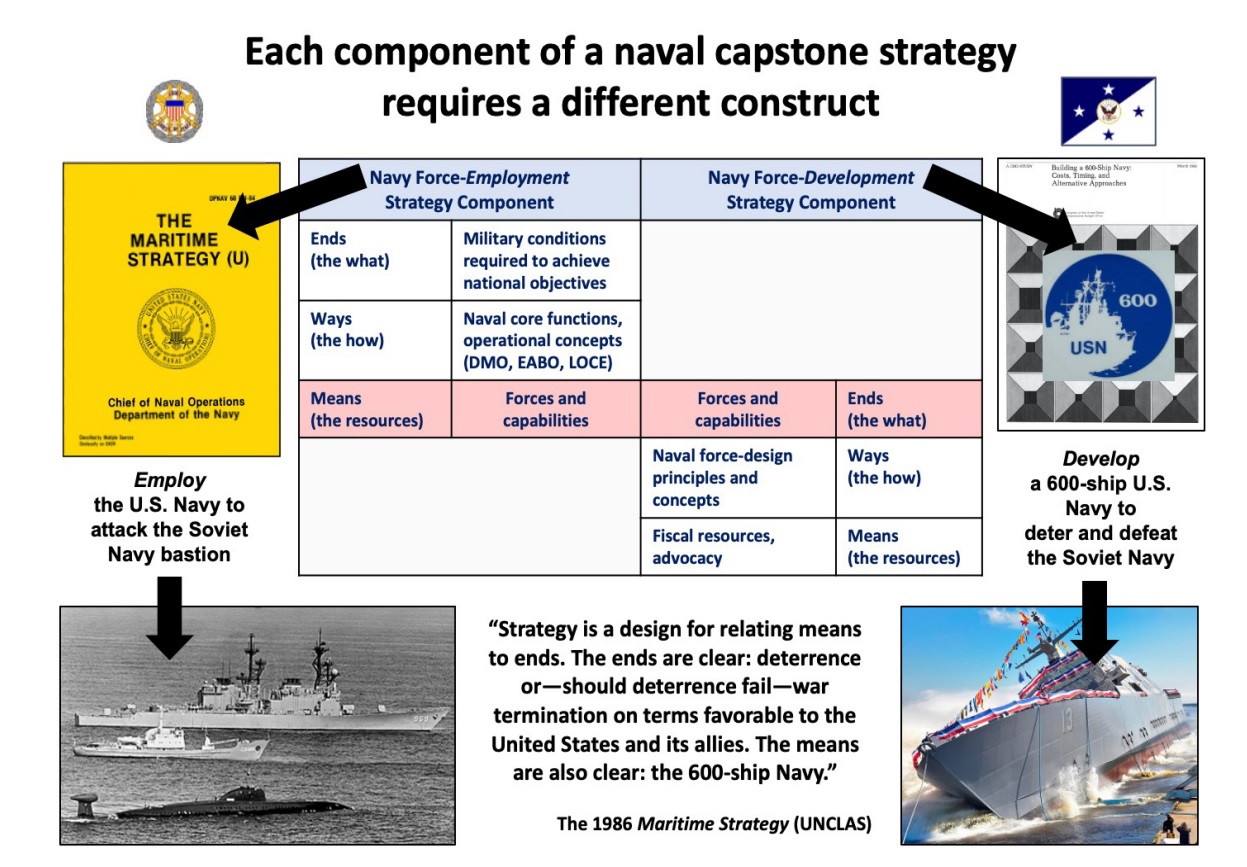

The graphic above conveys an important point illustrated by the famous 1980s Maritime Strategy and the equally famous objective to reach a 600-ship Navy. The former was a Navy force-employment strategy with a central idea of offensively attacking the Soviets’ Barents Sea bastions to deprive them of a maritime sanctuary, while the latter was a Navy force-development strategy to build a Navy that could deter and, if necessary, defeat the Soviets. Depending on the strategy, the forces and capabilities are either the means or the ends.

Note that, in this post-Goldwater-Nichols era, the force-employment component is not a strategy to fight. LOEs, phasing, and other tools for fighting are not best addressed in a service capstone strategy. Today and into the future, the Navy mans, organizes, trains, and equips its future force for the fight, but does not fight by itself. Therefore the force-employment-strategy component is more an expression of how the Navy will fight and how a conflict may unfold. This allows the OPNAV staff to pursue solutions for maintaining the current force and building the future force.

Observation 37

Your strategy must be capable of informing resource allocation for force development. Navy budget programmers considered the 2007 Cooperative Strategy to be “not useful” for articulating requirements and defending budgets; the 2015 version of this strategy (CS21R) likewise was not considered particularly useful. Indeed, CNO Jonathan Greenert (2011–15) did not construct three of his annual posture statements for Congress around this strategy.

While there is no hard-and-fast rule for how to design a strategy document so that it informs resource allocation, starting the crafting of a strategy without a firm recognition that part of its purpose is to give guidance to budget programmers is a mistake.

Observation 38

Drafting a strategy is only a first step, albeit a difficult one. The crafter needs to develop the strategy with implementation in mind. Here is how to institutionalize strategy:

• Begin by inserting high-level implementation taskers into the body of a Navy strategy to signal that the strategy is real, relevant, and significant—not to be ignored.

• Produce an implementation plan that specifies the processes, activities, and objectives required to achieve the ends of a Navy strategy.

• Translate the ends of a Navy strategy into measurable implementation objectives

linked to DCNO and subordinate organizational goals.

• Assign owners to each objective and initiative, for clear responsibilities and accountability.

• Conduct periodic progress reviews of implementation to monitor execution.

• Oversee execution by active senior leadership and drive implementation across the Navy by dedicated operational planning teams.

• Communicate strategy repeatedly to explain its logic and achieve buy-in.

Leaders habitually underestimate the challenge of implementing strategy. Follow-up procedures are needed to ascertain whether implementation is being carried out effectively. The follow-up should include the actions listed below:

• Conducting periodic progress reviews of implementation to determine whether the strategy is relevant to the Navy’s purpose. Since the Navy operates in a very dynamic environment, the reviews are essential to know whether the strategy is meeting the Navy’s needs.

• Assigning objectives and initiatives to individual “owners.” Accountability drives implementation. The implementation plan requires that clear and specific tasks be defined to implement the strategy. Everyone with implementation responsibilities needs to know what to do and what to achieve.

• Selecting the correct strategic metrics to track progress on the objectives or initiatives identified in the implementation plan. Measurable objectives provide an effective basis for management control of the implementation.

• Ensuring that senior leaders actively manage the execution of the strategy and guide implementation across the Navy. The focus should be on ensuring that the strategy is understood throughout the Navy.

The quote by retired Army colonel Ralph Peters is an appropriate description of strategies that are executed poorly.38 No matter how simple, logical, and eloquent, they amount to little if they do not have a positive result; hence the need for crafters of strategy to be concerned with—and involved in guiding—their execution.

Observation 41

For military and naval assessments, the term risk is used in the following different ways:

• as a synonym for a threat itself;

• as a description that identifies chance of harm or injury from a threat;

• as an expression of the mathematical result of frequency of occurrence multiplied by consequence

• as an expression of whether forces can accomplish assigned missions—in other words, risk as a result of operations.

All these forms generate the famous “friction” of the unpredicted. In crafting strategy, there never will be sufficient resources or predictability to eliminate risk completely, so one must analyze the strategic environment properly and make informed decisions that

both mitigate and accept appropriate degrees of risk. Unfortunately, there is no ready formula.

Risks must be listed in a context of realism, along with the means to address them. Risk to the Navy can be categorized within four dimensions: operational, force management, institutional, and future challenges.

• Operational risk deals with the short-term challenges facing the Navy, as well as our ability to succeed in the current fight, including preparedness for contingencies in the near term.

• Force-management risk deals with ensuring that the Navy is efficiently and effectively organized, manned, equipped, trained, and sustained to provide trained and ready forces to the force commanders.

• Institutional risk addresses the generating force’s ability to support the Navy’s operating force.

• Future-challenges risk deals with the Navy’s ability to address longer-term threats.

The Navy mitigates exposure to risk by ensuring that the right capabilities and sufficient capacity are balanced and available within acceptable bounds of risk to respond effectively and efficiently to challenges.

Col. Mackubin T. Owens, USMC (Ret.), notes the following:

“A good strategy also seeks to minimize risk by, to the extent possible, avoiding mismatches between strategy and related factors. For instance, strategy must be appropriate to the ends as established by policy. Strategy also requires the appropriate tactical instrument to implement it. Finally, the forces required to implement a strategy must be funded, or else it must be revised. If the risk generated by such policy/strategy, strategy/force, and force/budget mismatches cannot be managed, the variables must be brought into better alignment.”39

Observation 42

How can one grade a strategy document on its probable effectiveness? As with everything involved in the crafting of strategy, there are no hard-and-fast answers. However, one can evaluate the product in terms of (1) acceptability, (2) feasibility, (3) suitability to the circumstances, (4) sustainability, and (5) adaptability.

• Acceptability to the leadership is obvious; if—in terms of naval strategy—the product is not acceptable to the CNO, it is going nowhere.

• Feasibility requires an assessment of whether the Navy has or (probably) will have the resources to carry out the strategy. A strategy can be aspirational in the sense that it can be used as an argument for more resources; however, it must be adaptable enough to be implemented with a reasonable probability of success—not with no or even low risk, but with justifiable risk.

• Suitability to circumstances refers to the product’s conformity to national objectives. A strategy that postulates a threat that the political leadership does not recognize will be controversial, to say the least.

• Sustainability refers to more than supporting resources; it also encompasses whether personnel can carry out the product’s implications over the long term. A strategy that postulates substitution of autonomous systems for human control cannot be carried out if there is insufficient funding for such systems at the same time that manpower is being cut. The U.S. Navy has had previous experience with not having enough personnel to operate complex systems that optimistically were assumed to be “lower maintenance.” Without an honest and rigorous examination, it is possible to assume that a strategy will be easier to implement than reality dictates.

• The apocryphal quote by Field Marshal von Moltke cited in the introduction—that “no plan survives contact with the enemy”—can be translated as saying that no strategy can survive a changing security environment if adaptability is not built into its design.

Observation 43

With one exception, observation 43 is a collecting together of points made previously, restated as a guideline on what easily contributes to failure in the crafting of strategy. Number 43 is, in fact, the most significant observation of all in distinguishing successful efforts from failed attempts. In my experience, these are not mere suggestions; rather, failure to recognize any one of the above truths will damage fatally any effort to develop a strategy. Of course, recognition of the reality of these dangers is not enough; the crafters of strategy always must have a plan to mitigate the dangers or otherwise use and benefit from that reality.

The one point not previously discussed is the separation of the crafters’ egos from the product crafted. It is easy for writers to fall in love with their own words, for those with insight to become enamored of their own ideas, and for intermediate reviewers to be committed to their edits. Yet the final document—which will reflect the decisions of the issuing authority (the CNO)—may appear vastly different from previous versions. In such a process, pride of authorship becomes a burden, particularly when submitted drafts are returned repeatedly for additional editing. Crafting strategy is not about the strategists or their intervening chain of command; it is about the product.

This truly is hard stuff.

Bruce B. Stubbs, SES, is Director of Navy Strategy, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV N7).

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (Aug. 24, 2021) Ships from the United Kingdom Carrier Strike Group and the USS America Expeditionary Strike Group, with the embarked 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), begin multinational advanced aviation operations in support of Large Scale Global Exercise (LSGE) 21, Aug. 20, 2021. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Aron Montano)