The following was originally published by the Leidos Chair of Future Warfare Studies of the Naval War College under the title Crafting Naval Strategy: Observations and Recommendations for the Development of Future Strategies. Read it in its original form here. It is republished here with permission and several excerpts will be featured.

Read Part One.

By Bruce Stubbs

Observation 13

As previously noted, the term theory of victory can be somewhat confusing. There is no formal DoD definition for it, but broadly it is a hypothesis of how a nation intends to achieve strategic objectives during a conflict. It articulates how and why we think our actions will work. Ultimately, we use military force to change other nations’ will or wills. A theory of victory describes how we think our tactical- and operational-level actions will lead to achieving our strategic-political objectives.

The United States was supreme at the tactical and operational levels in Vietnam, but that dominance did not lead to a strategic or political victory. We had no successful theory of victory to link tactical- and operational-level successes to political victory.

A theory of victory is the conceptual means of establishing clear ends in the ends-ways-means equation. “Defining strategy in this manner gives us a tool for identifying a strategy, analyzing the conceptual clarity and logic of the strategy, and assessing the quality of the strategy. It provides a broad foundation from which all types of strategy can be defined, analyzed, and assessed, including corporate strategy, grand strategy, and military strategy.”21

Observation 14

In addition (or perhaps as an alternative) to beginning with a theory of victory, drafters of strategy should identify the central idea around which the document is to revolve. A very valuable treatise on strategy issued by the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence states as follows:

• “The innovative and compelling ‘big idea’ is often the basis of a new strategy.”

• “A strategy which has no unifying idea is not a strategy.”

• The central idea must bind the ends, ways, and means—and inspire others to support it.

• “In practice, the intent of all good strategies can be summed up in a page if not even better—in a paragraph.”22

This is the most concise summary I have found concerning the need for a central idea in any drafting of strategy.

Hollywood movies provide outstanding examples of how an entire production can be built around a concisely stated central idea. The movie industry refers to a statement of the central idea as a log line, as in the example below.

This log line for the movie Jaws is one of the greatest of all time. It depicts the overarching storyline in an interesting, straightforward way, rather than focusing on details that might seem meaningless without the context of the bigger picture. It captures the entirety of the plot—and thus the essence of what the audience will experience—in a single sentence.

In communications, the human brain craves meaning before details. If the core message of a strategy can be captured in a single sentence, there is a higher probability the strategy will be effective. As noted in one of the endnotes to the introduction, the overarching American strategy during the Cold War can be summarized in one sentence: “to contain the expansion of the Soviet Union (and its influence) until the internal contradictions within communism bring about its own demise.” And that was what was achieved.

Observation 18

According to Samuel Huntington, the strategy—or, in Huntington’s words, the strategic concept—must explain the Navy’s role in implementing national security. It must describe how, when, and where the Navy expects to protect the nation. Without a strategy or a strategic concept of the Navy’s role, the public and political leaders will be (1) confused about the role of the Navy—uncertain whether its existence is necessary— and (2) apathetic to Navy requests for additional resources.

Note again Huntington’s use of the term strategic concept, not strategy. As Huntington uses it, strategic concept is similar to the term value proposition, and relates to what the introduction describes as the strategic vision. Again, this is much different from what the Joint Staff considers to be a concept.

What follows below is an expanded description of the Navy’s value proposition.

U.S. naval forces can be visible or invisible, large or small, provocative or peaceful, depending on what serves American interests best. The sight of a single U.S. warship in the harbor of a friend can serve as tangible evidence of close relations between the United States and that country or their commitment to each other. American naval forces can modulate their presence to exert the kind and degree of influence best suited to resolve the situation, whatever it is, in a manner compatible with U.S. interests. In a crisis in which force might be required to protect U.S. interests or evacuate U.S. nationals, but where visibility could provoke the outbreak of hostilities, American naval forces can remain out of sight, over the horizon, but ready to respond in a matter of minutes.

U.S. naval forces do not have to rely on prior international agreements before taking a position beyond a coastal state’s territorial sea in an area of potential crisis; U.S. naval forces do not have to request overflight authorization or diplomatic clearance. By remaining on station in international waters, for indefinite periods, naval forces communicate a capability for action that ground or air forces can duplicate only by landing or entering sovereign airspace. U.S. naval forces can be positioned near potential trouble spots without the political entanglement associated with the employment of land-based forces.

Although bases on foreign soil can be valuable, U.S. naval forces do not require them in the way that land-based ground and air forces do. Ships are integral units that carry with them much of their own support, and through mobile logistics support they can be maintained on forward stations for long durations. U.S. naval forces, moreover, are relatively immune to the politics of host-nation governments, whereas those governments can constrain operations by land-based forces significantly. As the U.S. military base structure overseas has diminished over recent decades, the ability of naval forces to arrive in an area fully prepared to conduct sustained combat operations has taken on added importance.

Observation 20

The essence of strategy is the making of hard choices. Unfortunately, most strategies, especially at the unclassified level, studiously avoid making hard choices; however, the reality of finite resources forces us to make these choices.

Listed below are several classic choices that strategists face that you should address early in your production process:

• State which objectives are not going to be pursued

• Describe how and where risk will be accepted

• Establish a pecking order for resources to achieve objectives

Observation 25

Almost every book on strategy insists that the crafters need to meet with the top leadership/chief executive officer (CEO) to ensure that guidance is direct and clear. As discussed earlier, this often is difficult. Yet it is imperative that the strategists have some degree of direct access if their efforts are to yield an approved, effective result that the leadership is committed to executing. An initial meeting should be held at the beginning of the project. Frequent and unimpeded access is needed to accomplish the following:

• Implement CNO guidance—not guidance altered by the agendas of the OPNAV directorates

• Provide unfiltered advice to the CNO, especially alternative views

• Proceed quickly and with a minimum of interference from others

• Ensure linkage between the strategy and the program objective memorandum

(known as a POM), other elements of the resource-development, force-capabilities, and force-development processes, all of which the CNO directs (the strategists/crafters need to remind the CNO of this necessary linkage)

• Ensure that the CNO receives Navy strategy products that reflect a consistent and aligned set of principles, concepts, and tenets regarding the Navy’s fundamental role in implementing national policy.

In his guidance to the drafters of the 2018 National Defense Strategy, then-SECDEF James N. Mattis (2017–18) stated, “As a practical matter, strategy cannot be built by a large group process. [OSD and the JS will lead a small team reporting directly to me.] . . . I will be personally involved in this effort. . . . The team will provide interim products. . . . These products may be provocative, as any good strategy requires hard choices. I expect you to review these as a means to genuine debate.”30

Almost every defense official has expressed and expresses similar sentiments, but that does not mean they are translated into direct meetings with their strategists. Given the time constraints the senior leader (in this case, the CNO) faces, as previously discussed, the “front office” (which manages time and appointments) is unlikely to initiate an invitation. So the initiative to meet with the CNO must come from the crafters themselves (or their immediate boss), and they figuratively may have to “fight for it.” However, such fighting is necessary if the crafters are to do their work efficiently and avoid becoming overwhelmed by frustration and cynicism.

Observation 29

A strategy that cannot be communicated effectively is an ineffective strategy. The crafters of strategy not only bear a responsibility to make it understandable but must take the lead in building a strategic communications plan. You never can rely wholly on outside specialists (such as public affairs officers) to come up with a strategic communications plan. They simply do not know the strategy as intimately as the crafters do; thus they may not be able to capitalize on the nuances and internal messaging.

Build your strategic communications plan around the central idea. Have a clear core message. Your rollout plan must engage across multiple media venues. Have a scalable message suitable for any size venue. Understand that every action is a message—a strategic communication. Synchronize the message inside and coming from OPNAV and echelon components.

Observation 30

Whether or not one agreed with President Ronald W. Reagan’s policies or decisions, no one can deny that he was a great communicator who made his goals for his presidency simple and clear. He incorporated this core message into almost all his speeches, relating specific decisions to his general goal. Through this approach, the core message became a guiding philosophy, generating corresponding lines of effort for problem solving.

The single-core-message approach makes for a tight, internally consistent strategy and a subsequent network of supporting plans. Notice, too, that President Reagan’s message confined itself to three points.

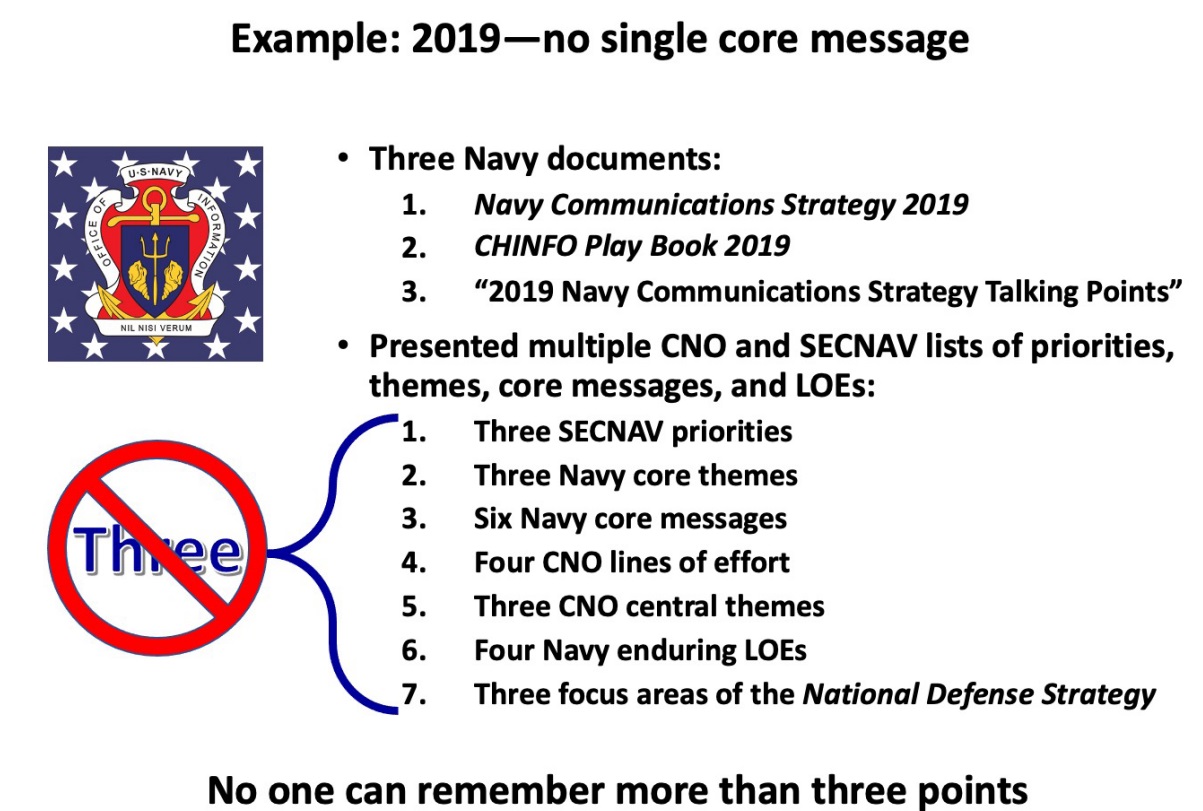

This approach deserves emulation in any crafting of strategy. Unfortunately, the recent Navy attempts at strategy have not emulated this approach, particularly in 2019.

With so many different lists of priorities, themes, core messages, and lines of effort (LOEs) in 2019, it was difficult for the Navy to communicate its strategic policy goals with a single voice, so it could stay on message and be understood. There never was a real agreement on the Navy’s mission and desired end state.

The mission:

• From the Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV): “The Department of the Navy will recruit, train, equip, and organize to deliver combat-ready naval forces to win conflicts and wars while maintaining security and deterrence through sustained forward presence.”

• From the CNO: “The United States Navy will be ready to conduct prompt and sustained combat incident to operations at sea. Our Navy will protect America from attack, promote American prosperity, and preserve America’s strategic influence.” (Note that this is just the first two sentences of the four-sentence mission statement in the CNO’s Design 2.0 directive.)

The vision (or end state):

• From the SECNAV: “A combat-credible Navy and Marine Corps Team focused on rebuilding military readiness, strengthening alliances, and reforming business practices in support of the National Defense Strategy.”

• From the CNO: “A Naval Force that produces leaders and teams, armed with the best equipment, who learn and adapt faster than our rivals to achieve maximum possible performance and is ready for decisive combat operations.”

Given that these lists, missions, and end states all reflect SECNAV and CNO direction, not much could have been done to align and simplify the Navy’s overall strategic message. There simply was too much divergence in language.

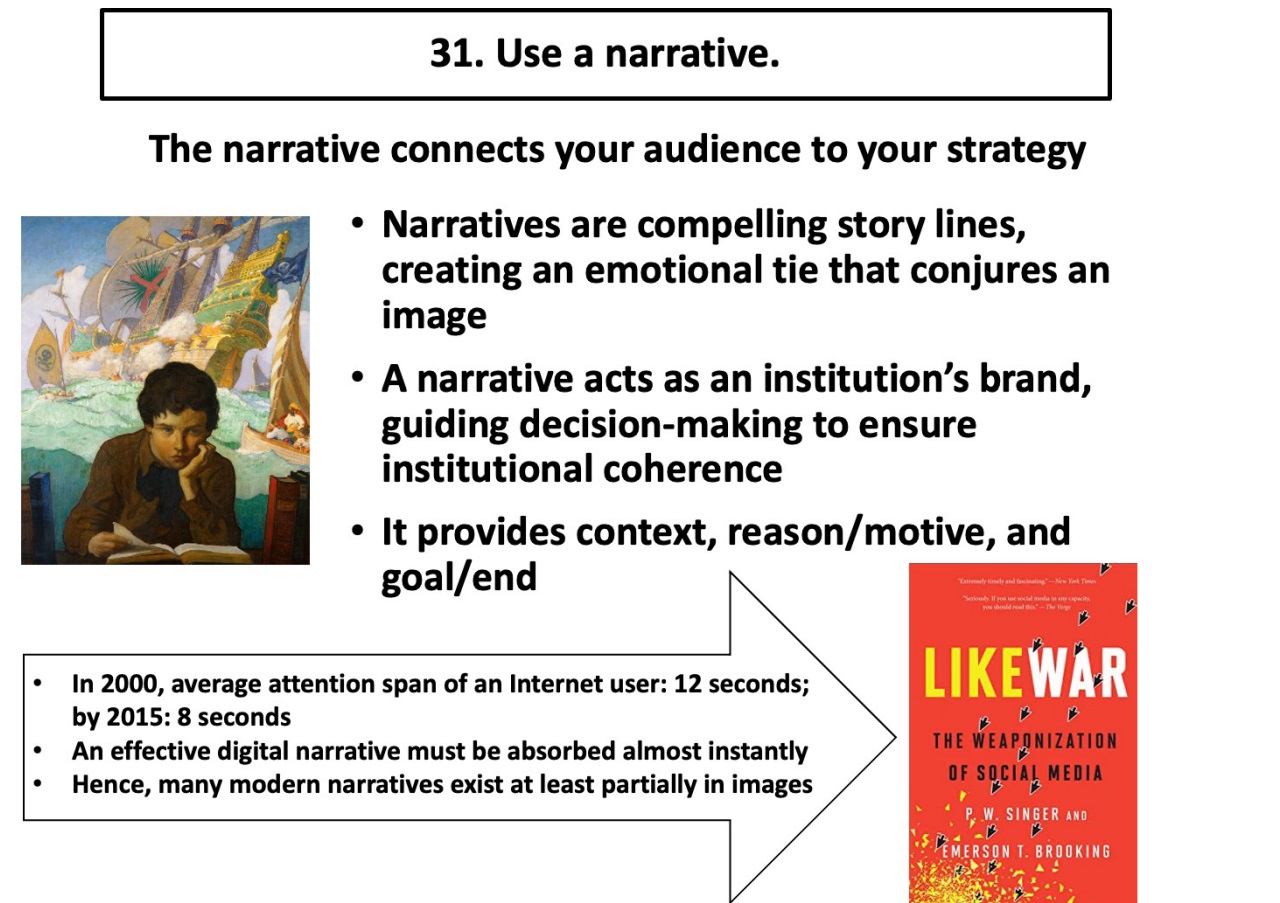

Observation 31

Authors Peter W. Singer and Emerson T. Brooking write the following about the importance of narrative in today’s world:

“Narratives are the building blocks that explain both how humans see the world and how they exist in large groups. They provide the lens through which we perceive ourselves, others, and the environment around us. They are the stories that bind the small to the large, connecting personal experience to some bigger notion of how the world works. The stronger a narrative is, the more likely it is to be retained and remembered.

The power of a narrative depends on a confluence of factors, but the most important is consistency—the way that one event links logically to the next. . . . As narratives generate attention and interest, they necessarily abandon some of their complexity. . . .

By simplifying complex realities, good narratives can slot into other people’s preexisting comprehension. . . . The most effective narratives can thus be shared among entire communities, peoples, or nations, because they tap into our most elemental notions. . . .

These three traits—simplicity, resonance, and novelty—determine which narratives stick and which fall flat. It’s no coincidence that everyone from far-right political leaders to women’s rights activists to the Kardashian clan speaks constantly of “controlling the narrative.” To control the narrative is to dictate to an audience who the heroes and villains are; what is right and what is wrong; what’s real and what’s not. As jihadist Omar Hammami, a leader of the Somali-based terror group Al-Shabaab, put it, “The war of narratives has become even more important than the war of navies, napalm, and knives.”

The big losers in this narrative battle are those people or institutions that are too big, too slow, or too hesitant to weave such stories. These are not the kinds of battles that a plodding, uninventive bureaucracy can win. As a U.S. Army officer lamented to us about what happens when the military deploys to fight this generation’s web-enabled insurgents and terrorists, “Today we go in with the assumption that we’ll lose the battle of the narrative.”35

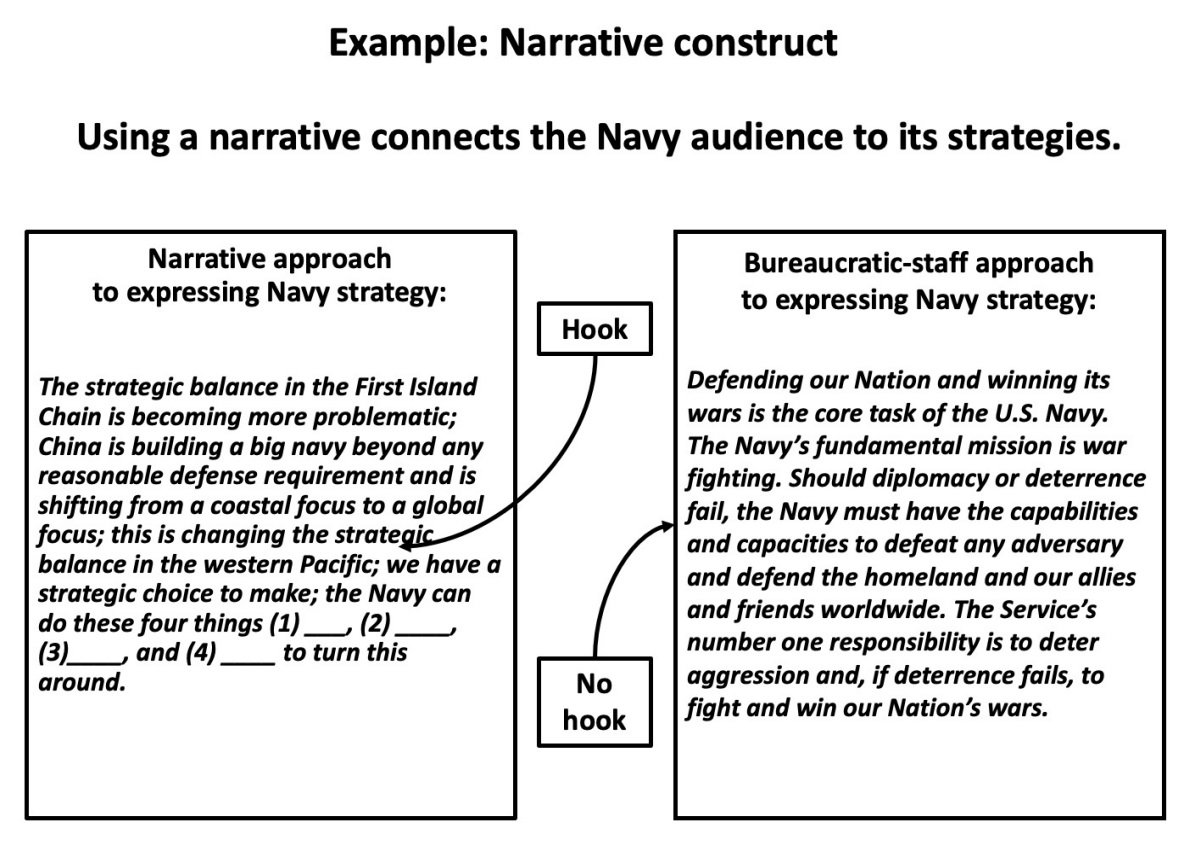

Since we do not want to “lose the battle of the narrative,” it is imperative that we apply a narrative approach to the crafting of naval strategy, as in the example below.

My own awareness of the power of the narrative approach started with an e-mail from Andrew F. Krepinevich Jr., a retired U.S. Army colonel, author, and CEO of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, in February 2016. Krepinevich suggested that we not use the core attributes or characteristics of the Navy in isolation as the foundation of our message. Instead, he recommended that we attach a relevant, understandable purpose to each attribute by answering the question “To do what?” He gave an example from a conversation he had with a congressman, who stated, “I kinda get a 30-slide, high density, small font brief when it’s presented, but a week later, I can’t give you the logic train behind the brief.”

So Krepinevich suggested using the text shown here. The kernel of his suggested narrative is crystal clear and easy to remember: “China is building a big navy that is changing the strategic balance in the western Pacific.”36 In contrast, the bureaucratic staff approach simply does not grab the reader’s attention; it lacks specificity and real-world logic, and generally is too abstract—which is fairly representative of military staff writing.

Bruce B. Stubbs, SES, is Director of Navy Strategy, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV N7).

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (Nov. 17, 2021) Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Gridley (DDG 101) transits the Pacific Ocean during a navigation exercise. Gridley is underway conducting routine operations in U.S. 3rd Fleet. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Colby A. Mothershead)