The following article is published in English and Chinese.

By Tommy Jamison

The present dispute over the South China Sea doesn’t hinge on fishing rights, or oil fields, or even military bases. At its root the controversy stems from conflicting, profoundly held and historically consistent “core interests/核心利益.” On the one hand, the United States sees freedom of navigation as a fundamental pillar of the post-war order and integral to the past 70 years of relative peace and prosperity. On the other, China’s (re)assertion of sovereignty over the South China Sea should be contextualized within its century long campaign to recover territory lost under (semi)-imperialism. The historical grounding of both these arguments seems lost on much of Washington as well as Beijing.

目前南海冲突的关键不是捕鱼权,不是油田,甚至也不是军事基地。从根本上讲,南海争议来源于不同的,有历史一致性的的核心利益。在一方面,美国认为航行自由是实现与二战以来持续七十年的安全与繁荣的重要基础。反过来,中国对南海的领土的主张跟其具有一百多年来“反殖民主义”的历史经历有很大的关系,我们应该思考这一背景。华盛顿跟北京一样,似乎都对双方的历史情况漠不关心。

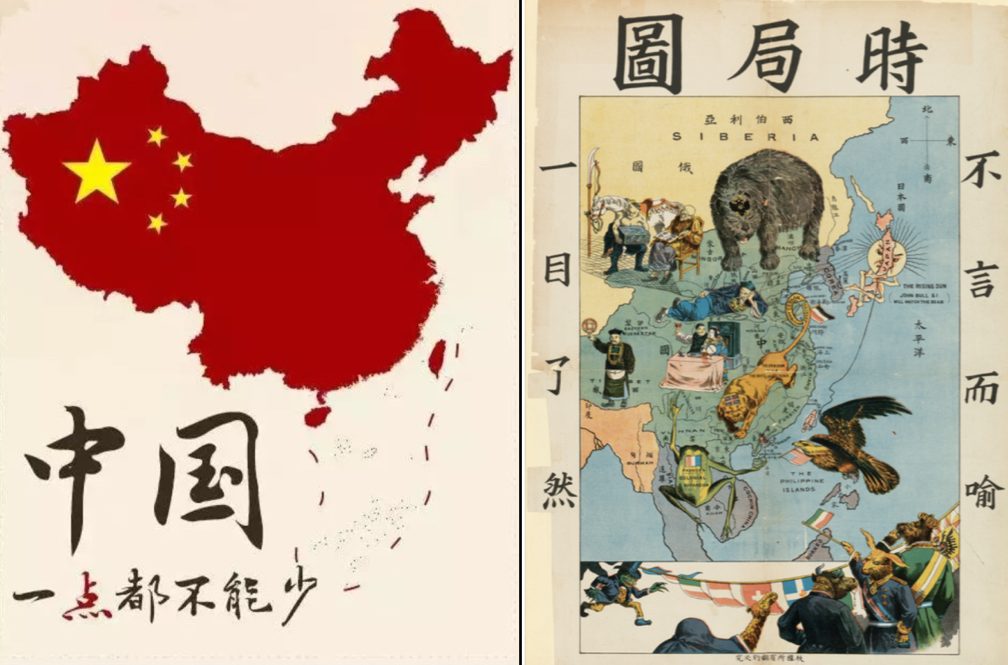

Territorial controversies are not new in China. From the Opium War (1839-42) to the present, resisting imperialism and recovering lost territory have constituted core objectives of Chinese foreign policy. As such, it is only through first exploring this historical context that we understand the modern conflict in the South China Sea. Because of “Western” (semi)-imperialism, territorial disputes in Chinese modern history are very common and have profound political ramifications. The question of Shandong’s sovereignty was the fuse for the May Fourth movement (1919); Japan’s aggression in Manchuria (1931) led to the collapse of the post-WWI internationalist system and incited the Second World War; before 1997 Hong Kong was one of the world’s last formal colonies; today Sino-Taiwanese relations remain a powder keg, and so on. From this historical perspective of course the South China Sea is a sensitive question. It is also in some ways a legacy of resistance to imperialism and, to a certain extent, a continuation of the 20th century movement to recover lost territories.

中国的领土争议由来已久。从鸦片战争至今,反殖民主义与收复失地可以说是中国外交的核心目标之一。因此,我们首先要了解近代中国的历史背景,唯有如此,才能更好地了解现在的南海矛盾。由于西方帝国主义,在中国近代历史上类似的领土问题中无处不在,并产生深远的政治影响。山东省的主权问题是五四运动(1919)的导火线;日本在东北的侵略导致了一战后国际秩序的崩溃,也引发了第二次世界大战;1997之前,香港算世界上最后的正式殖民地之一;今天两岸关系还是一个“火药桶”等。从历史脉络的角度来看,南海主权理所当然是一个敏感的政治话题。同时,从某种角度上是反殖民主义的精神遗产,而且在一定程度上是二十世纪主权运动的继续。

At the same time, from a macroscopic perspective, the U.S. post-war diplomatic strategy can be summarized in four principles: 1) defend democratic regimes; 2) encourage free trade; 3) protect freedom of navigation, because it is a fundamental requirement of free trade (alongside today freedom of information, the skies and even space); and 4) spread liberalization, an admittedly abstract principle. In short, the U.S. post war strategy has been an attempt to replace the pre-war anarchic international system with a liberal internationalist system. China’s activity in the South China Sea threatens these aims, particularly freedom of navigation, and thus threatens the post-war international system. Freedom of navigation is often criticized in mainstream Chinese media, as in, “At root, freedom of navigation is an excuse to implement the ‘pacific rebalance’ strategy and to contain the emergence of China,” but the present world was developed from these ideals. As such, freedom of navigation is in no way an empty slogan, but rather a core U.S. interest.

与此同时,在宏观层面上,美国二战后的外交战略可以归纳为四个原则:一是保护民主政府;二是推动自由贸易;三是捍卫航行自由,因为航行自由是贸易自由最基本的要求,现在这个原则扩展到飞行自由、信息自由,甚至天空自由等范围。第四个原则是最抽象的——普及自由化。简而言之,美国二战后的战略试图用自由国际秩序来代替二战前的无政府国际秩序(anarchic international system)。如今,中国在南海的行为威胁到了这些原则,特别是航行自由,因此也威胁到了二战后的国际秩序。中国主流媒体常常讽刺航行自由,比如“归根结底是借推行航行自由之名,行推进亚太再平衡战略、遏制中国崛起”等,但是目前的世界格局正在这理念之上发展而来。因此,航行自由绝非一个凭空的口号,而是一个核心利益。

None of this is to say that today’s South China Sea controversy is a direct continuation of China’s resistance to imperialism—far from it—but only to suggest that the conflict’s acuteness cannot be divorced from a larger historical context. When writing his history of Sino-U.S. relations from 1989-2001, David Lampton appropriated a saying about spousal conflict to sum up his findings: Same Bed, Different Dreams (同床异梦). That’s about right for the South China Sea as well. Still, the more worrying phrase might be the oft heard, “one mountain cannot hold two tigers” (一山,不容,二虎), which not coincidently frames the last chapter of Sarah Paine’s excellent history The Wars for Asia (1911-1949). Given the significance of historical context in this dispute, the potential for the misuse of history is likewise apparent. Eric Hobsbawm once wrote, “Historians are to nationalism what poppy-growers in Pakistan are to heroin-addicts: we supply the essential raw material for the market.” That danger seems particularly applicable to South China Sea where the trends of nationalism, hegemony, ecological scarcity and globalization intersect.

Still, one thing is for sure, giving serious thought to the historical background informing behavior on both sides of the Pacific would go a long way toward dispelling the distortions of modern day nationalists and bureaucrats alike. It might even help prevent an especially unnecessary war.

Tommy Jamison is a PhD Candidate in International History at Harvard University. He served as an officer in the U.S. Navy between 2009-2014.

Featured Image: South China Sea Goddess of Mercy 南山海上观音圣像. (Percy)

Japans aggression in China wasn’t THE cause of World War Two. It is generally accepted that World War Two started on 1st September 1939 when Nazi Germany invaded Poland with war being declared by Britain and France at 11am GMT on 3rd September 1939. The cause of World War Two can actually be traced back to the Treaty of Versailles which encumbered Germany with highly punitive war retributions, that in the end wrecked the German economy, allowing for the rise of Hitler and the Nazis to power. Japans aggression in the Pacific widened World War Two and the only reason the USA became involved in the European part of the war, when it did, was because Hitler had a brain explosion and declared war on the US. If he hadn’t, history may have been different. My country (NZ) and the rest of the British Commonwealth had already been at war for two years, three months when the US entered the war.