Written by Matthew Merighi for Movie Re-Fights Week

The Battle of Endor was the ultimate confrontation in the original Star Wars trilogy. It was a two-pronged battle both in space and on the surface of Endor. Each was a desperate race against time; the Rebel Fleet desperate holding out against the Imperial Fleet backed by a fully armed and operational Death Star laser while a strike team battled a full Imperial Legion defending the Death Star shield generator. We all know how the story ends: the plucky Rebels manage to overcome the Legion through successful use of indigenous forces and coalition warfare, allowing the Rebel Fleet to destroy the Death Star from the inside. The Death Star explodes, the evil Emperor dies, and the galaxy is finally free of tyranny. The end.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

While this makes for good cinematography, it makes for poor understanding of military strategy. As the television show Robot Chicken points out, there is no reason why the Rebels should have won that battle even once the Death Star was destroyed. The Imperial Fleet was still very much intact, though down a Super Destroyer, and could have prevailed in a protracted conventional engagement. Moreover, the Emperor’s initial strategy to hold the Imperial Fleet in reserve in order to demonstrate the Death Star’s power and fuel Skywalker’s despair in his fall to the Dark Side was clumsy at best. Palpatine demonstrated what happens if you do not pay attention during strategy classes.

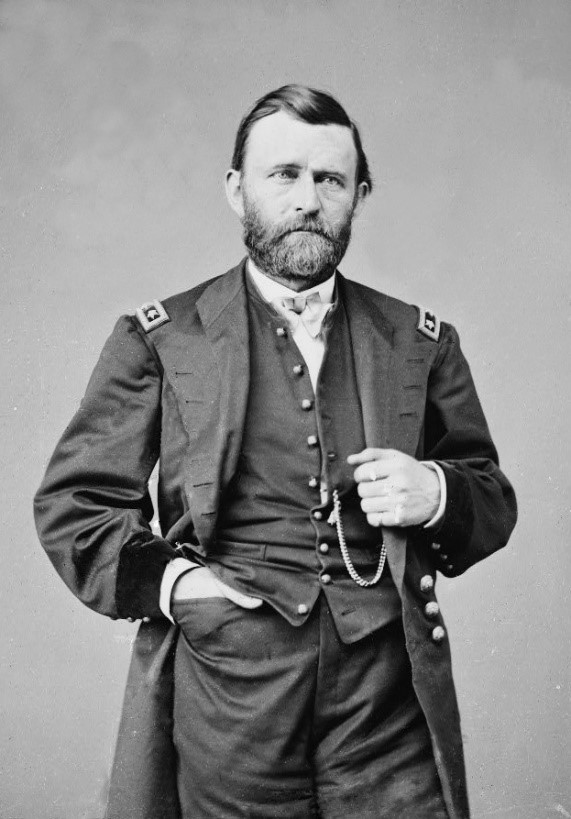

In crafting a better strategy at Endor, the Empire could have turned to a figure from American military history: Ulysses S. Grant. For our historically impaired audience, General Grant was the commander of Union forces during the American Civil War who distinguished himself through quasi-Soviet strategy of using superior manpower to slowly grind down the Confederacy until it surrendered. He is one of the best examples of a successful attrition-based approach to strategy and tactics. He followed the dictum that “quantity has a quality of its own.”

The Union’s Grand Army of the Republic (double entendre intended) exhibited the same characteristic as the Imperial Fleet: it was larger and better outfitted but less ably manned and led than its Rebel counterpart. This did the Union no favors in the early phase of the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln fired Grant’s predecessor, George McClellan, for failing to act aggressively with the Union’s numeric advantage. “If General McClellan isn’t going to use his army,” Lincoln fumed, “then I would like to borrow it for a time.”

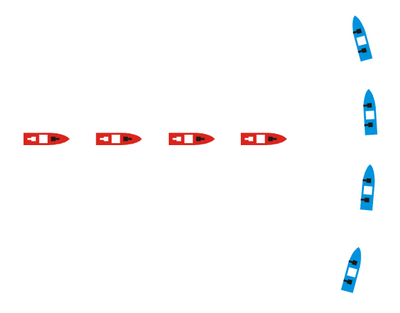

If Grant was directing operations at Endor, he would immediately engage the Rebel Fleet. He had enough numbers to overwhelm the Rebel Fleet early while they were still processing the trap the Empire laid. He also had optimal field position. The Rebel Fleet was trapped on three sides by the Death Star, Endor, and the Imperial Fleet. The Rebels were also strung out in a long column while the Imperial Fleet was in a broad line. Imperial Star Destroyers, with their superior armaments and optimization for firing at targets to their front, “crossed the T” and pummeled the ships in the Rebel vanguard before the heavy cruisers in the rear could get into good firing range.

Grant’s approach does have a downside: the risk of a Pyrrhic victory. The Imperial Fleet is not just a warfighting tool; it is also a tool of domestic policing. The Empire is held together through fear of the Imperial Fleet, so conventional losses at Endor could have been a political disaster when coupled with Emperor Palpatine’s death. Grant would have accepted those risks and proceeded with his strategy. He would have reasoned that, despite the short-term challenges of replacing losses, the Rebels would have much more difficulty recovering from such a slugfest than the Empire would. Grant might also have reasoned that it would be much easier to bind together a government by NOT being a pro-human racist or building giant planet-killing superweapons that would ruin the galactic economy but that is neither here nor there.

Remember strategists: focus on your most important objectives, use your advantages wisely, and don’t be afraid to take risks. If you do, you too might defeat the Rebel Fleet one day.

Matthew Merighi is CIMSEC’s Director of Publications. He is a Masters of Arts candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. He is also a proud Star Wars nerd.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

Thanks for the wonderful photograph. I recommend that your take a look at Lee’s Army during the Overland Campaign: A Numerical Study by Arthur C. Young III. What you have written is the fiction that Jubal Early and others created to rationalize the Lost Cause. It has no basis in fact.

Interesting, but I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that the author falls into the common misconception that Grant fought a war of attrition. This is a myth that gained credence as part of the “Lost Cause” mythos. Grant certainly did make use of superior numbers, but he generally also conducted campaigns of maneuver. Just look at his campaign against Vicksburg. Even in Virginia, Grant routinely attempted to outmaneuver Lee. He succeeded several times, most notably in his crossing of the James River, in which he fooled Lee into thinking he was heading one way when he was actually moving his entire army in the opposite direction, but generally was thwarted by one of two factors – Lee’s ability to respond quickly using interior lines of March and communication, and the maddeningly slow movements of some of his corps commanders, notably Gouvernor K. Warren.

Petersburg is a prime example. If Grant’s subordinates had carried out Grant’s plan as executed, the city would have fallen rapidly and the entire grinding siege, which is one of the key underpinnings of the “war of attrition” notion, wouldn’t have taken place at all. Instead, however, General William “Baldy” Smith delayed his initial attack for several hours, for reasons that are known only to him, with the result that the Confederates were able to rush reinforcements to the area. What had been very lightly held fortifications when Smith arrived, manned by old men in numbers insufficient to repel even minor probes, became a heavily manned and virtually impregnable fortress by the time Smith finally attacked just before sundown. (He’d arrived at his launching-off point at dawn.)

So yeah, like I said, interesting, but this piece doesn’t display more than a beginners knowledge of what Grant actually did on the battlefield.