By Walker D. Mills

Introduction

Atlantic Cod vary in color from grey to greenish-brown and can grow to be as large as five feet long (though this is uncommon). The fish have long been a staple of diets across the North Atlantic and fishermen have crisscrossed those waters from the Grand Banks off Newfoundland to the North Sea to bring back cod to their home markets.

Not once, but three times in the 20th Century, cod was almost the causus belli between Iceland and the United Kingdom in a string of events referred to collectively as the “Cod Wars.”1 The Cod Wars, taken together, make clear that issues of maritime governance and access to maritime resources can spark inter-state conflict even among allied nations. Fishing rights can be core issues that maritime states will vigorously defend.

Fighting for Fish

In the spring of 1958, following the conclusion of several treaties resulting from the first United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS I), the Icelandic government announced that it would extent its territorial waters out to 12 nautical miles.2 Just a few years earlier, they had extended their territorial waters from three to four miles and caused a row with the British government, sometimes called the “Proto-Cod War.” The 1958 12-mile increase was much larger and almost singly directed at the British fishing fleet that trawled Icelandic waters for cod.

The United Kingdom, which had long supported only a three-mile territorial waters limit, was incensed. They reminded the Icelanders that they had been fishing cod in Icelandic coastal waters since at least the 15th Century.3 A large fleet of UK-based fishing trawlers regularly operated off the coast of Iceland, and well within 12 miles of the coast. This cod fleet was supported by processing plants and retailers back in the UK and was well-represented not only in the British Parliament but also well-regarded in public opinion.

In the months between the announcement and the coming enforcement of the extension it was not clear exactly what Iceland intended to do if the British trawlers did not leave voluntarily. Iceland had no navy and the Icelandic coast guard had only seven small ships with one gun each – almost all under 100 tons.4 In contrast, the Royal Navy was regarded as one of the world’s most powerful navies and the Icelandic coast was less than two days sailing away from Royal Navy bases in the United Kingdom.

The First Cod War started on September 1st, 1958. Icelandic coastguardsmen sought to arrest and impound any British trawlers within their new 12-mile limit. The Royal Navy established zones patrolled by frigates and destroyers to protect their fisherman. Their first clash came the following day on September 2nd, when Icelandic coastguardsmen from the Thor boarded the British trawler Northern Foam which had strayed out of the zone protected by British warships. But the Northern Foam was able to send a distress signal to one of the Royal Navy ships and soon a counter-boarding party from the HMS Eastbound boarded the Northern Foam as well and convinced the Icelanders to leave.5

The Icelanders, however, were not backing down. The health of their offshore cod fisheries had begun to significantly decline with as much as a 15 percent reduction in cod catch over the previous three years despite increases in the size of the fishing fleet.6 After two and-a-half years the British government backed down and acquiesced to the new 12-mile limit.

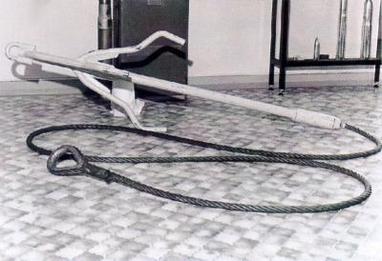

Ten years later the conflict began anew when Iceland announced that it would be extending the 12-mile limit to 50 miles effective on the first of September 1972. This “Second Cod War” was more intense and more violent, with multiple incidents of Icelandic coast guard vessels firing at or near British trawlers and many incidents of ramming by Royal Navy warships, British tugboats, and Icelandic coast guard vessels.7 The Second Cod War also saw the use of a new weapon in the anti-trawler fight by the Icelandic coast guard – a device for cutting trawler fishing nets. The coast guard vessels could fire a hook across the trawl lines of a fishing vessel and when they reeled their hook back in it would cut the net free of the trawler. Thus the fisherman would lose not only their catch but also their net.8

It was also during the Second Cod War that Iceland threatened to leave NATO (it was a founding member) and expel U.S. troops from Iceland, specifically their key base at Keflavik.9,10 This threat revealed the significant leverage that Iceland had in dealing with NATO despite not having a standing military. Iceland’s contribution to the alliance is its key location astride the North Atlantic, roughly halfway between Greenland and the United Kingdom. The nature of Iceland’s contribution to the alliance meant that it could not be replaced by another member or any other combination of members. Also, an Iceland out of NATO could have possibly looked toward the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact to be its new security guarantor.

In November 1975 Iceland initiated the Third Cod War when it unilaterally extended its territorial waters out to 200 miles. During the Third Cod War Iceland again threatened to withdraw from NATO and severed diplomatic relations with Britain for a time. British warships again clashed with Icelandic vessels, and collisions – both intentional and not – were common. Wire cutters were also used again to cut trawler nets. The dispute was again ended on terms favorable to Iceland in 1976, where Britain accepted the new 200-mile limit and received only limited and temporary fishing rights in return.11

Lessons for Today

If the Cod Wars are relevant today, then what are the important lessons decades after they have been settled? Three takeaways stand out. First, smaller, less powerful nations can successfully contest maritime disputes below the threshold of war. The Icelandic coast guard was successful in keeping British trawlers out of Icelandic waters – except for the three specific patrol zones established by the Royal Navy. Forcing the trawlers to operate in specific, tightly controlled zones significantly reduced their ability to fish and the size of their catch which were the ultimate goals of the extension of the territorial waters claim.

https://gfycat.com/alivethickhackee

Icelandic gunboat collides with British frigate in March 1976 (Footage via Associated Press)

Second, a critical part of the conflict was the asymmetry in will. Iceland, a much smaller nation than Britain with far fewer resources, simply had more willpower. In the words of Mark Kurlansky, author of Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, “The Icelandic government was shockingly tough.”12 They were even willing to go so far as to threaten to withdraw from NATO and kick U.S. troops out of Iceland to preserve the health of their fisheries. Britain, despite having dramatically more power overall, did not have the political will to fully employ their naval power against the Icelandic coastguard or the leverage to counter the Icelandic threat to leave NATO. The British Foreign Secretary and the Secretary for Fisheries and Food acknowledged that “NATO’s defenses in the North-Atlantic and the balance of power were more important than the interests of the Humber trawler owners and fishermen.”13

Third, issues of maritime governance and control (like fishing rights) can be seen as core issues to the nations concerned and can potentially lead to war. If this lesson comes as a surprise, it shouldn’t. Wars have been fought over what are purely maritime disputes since the Trojan War.14 Some authors have argued that because of the liberal ties between Iceland and the Britain full-scale war was simply not possible, but the possibility of armed confrontation was surely close to the minds of those involved.15

The United States, China, and their respective partners would do well to remember the Cod Wars as tensions rise in the Indo-Pacific where fishing access and maritime boundaries are central to several ongoing disputes.

Walker D. Mills is a Marine infantry officer currently serving as an exchange officer in Cartagena, Colombia. He has previously authored commentary for CIMSEC, the Marine Corps Gazette, Proceedings, West Point’s Modern War Institute and Defense News.

Endnotes

1. The name is attributed to the British journalist Llewellyn Chanter who covered the first Cod War for The Daily Telegraph. Gudmundur J. Gudmundsson, “The Cod and the Cold War,” Scandinavian Journal of History, Vol. 31, No. 2, (June 2006) 97.

2. Gudni Thorlacius Johannesson, “How ‘cod war’ came: the origins of the Anglo-Icelandic fisheries dispute, 1958–61,” Historical Research, vol. 77, no. 198 (November 2004) 557.

3. Gudmundsson, “The Cod and the Cold War,” 100.

4. Mark Kurlansky, Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1997) 162.

5. “Richard Nelsson, “Iceland v Britain: the cod wars begin – archive, September 1958,” The Guardian (7 September 2018) https://www.theguardian.com/business/from-the-archive-blog/2018/sep/07/first-cod-war-iceland-britain-fish-1958.

6. Kurlansky, Cod, 161.

7. Ibid, 166.

8. Sverrir Steinsson, “The Cod Wars: a re-analysis,” European Security, (March 2016) 4.

9. Steinsson, “The Cod Wars: a re-analysis,” 4.

10. John W. Young and John Kent, International Relations Since 1945: A Global History, 2nd edition (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013) 86.

11. Steinsson, “The Cod Wars: a re-analysis,” 4.

12. Kurlansky, Cod, 166.

13. Gudmundsson, “The Cod and the Cold War,” 101.

14. Trevor Bryce, “The Trojan War,” chapter in The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010) 480.

15. Sverrir Steinsson, “Do Liberal ties pacify? A study of the Cod Wars,” Cooperation and Conflict, (June 2017) 2-3.

Featured Image: HMS Scylla and Odinn collision during the Second Cod War (Wikimedia Commons)

Unfortunately the Chinese do not operate under Western norms – They are crooks and are underhanded, and “the end justifies the means” sums the Chinese better and more accurately than any other 5 words there are. Iceland and Britain cannot be compared to the Chinese.

Fascinating story. Thank you for that account of the cod wars.