This article originally featured in The Canadian Naval Review and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Sherman Xiaogang Lai

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is not an Arctic country but it was admitted into the Arctic Council in 2013, making the total at that time 12. (Today there are eight member states, plus 13 observer states as well as 13 inter-governmental organizations, and 13 non-governmental organizations.) The PRC is, nevertheless, not content with its current status and is determined to increase its voice in Arctic affairs by exploiting the Arctic situation for its economic and financial strength.1

It has been 40 years since Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997) started his market-oriented economic reforms in 1979. Through abandoning China’s Stalinist command economy and trading with the West (including Japan), Deng’s reforms brought the Chinese people a good life that their ancestors had not dreamed of. Trading with the West also enabled the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to build up a modern air force and a blue-water navy while providing it with sufficient financial resources to become a state with global influence. But, contrary to the expectations of the West that economic liberalization would lead to democratization, since 2012 the PRC has moved toward dictatorship under Xi Jinping’s leadership.2 As well, Deng’s economic reforms did not help solve a set of explosive issues inherited from Imperial China and the CCP revolution (1921-1949). Among the issues that remain to be resolved are the South China Sea, Taiwan, and Korea. These issues directly concern the legitimacy of the CCP’s rule. China’s Arctic policy, therefore, has to be examined in the context of its domestic politics and its geopolitical and geostrategic concerns.

The PRC’s Arctic Policy

In January 2018, five years after it was admitted into the Arctic Council, the PRC government released a 10-page white paper, “China’s Arctic Paper.”3 The white paper claims at the beginning that the melting of the Arctic sea ice has profoundly raised the Arctic’s strategic value as the intersection between North America, Europe, and East Asia, as a region of unexploited resources such as natural gas, oil and fish stocks, and as the birthplace of storms that will affect the entire northern hemisphere. The melting Arctic, according to the white paper, has a “direct impact on China’s climate system and ecological environment, and, in turn, on its economic interests in agriculture, forestry, fishery, marine industry and other sectors.” China, the white paper claims, is therefore a “Near-Arctic State” and “an important stakeholder in Arctic affairs.”

China also has “rights in respect of scientific research, navigation, overflight, fishing, laying of submarine cables and pipelines, … and rights to resource exploration and exploitation in the Area,” as stipulated in treaties such as UNCLOS and the Spitsbergen Treaty, and general international law. In addition, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, China “shoulders the important mission of jointly promoting peace and security in the Arctic.”4

In other words, the PRC government believes that China is entitled to rights in Arctic affairs. The white paper states that China is capable of claiming its rights of “utiliz[ing] sea routes and explor[ing] and develop[ing] the resources in the Arctic.”5 The white paper goes further by saying that “China’s capital, technology, market, knowledge and experience is expected to play a major role in expanding the network of shipping routes in the Arctic and facilitating the economic and social progress of the coastal States along the routes.” The white paper states that China’s goals and approaches in the Arctic are “to understand, protect, develop, and participate in the governance of the Arctic, so as to safeguard the common interests of all countries and the international community in the Arctic, and promote sustainable development of the Arctic.” As proof to support China’s right, the white paper traced China’s participation in the Svalbard Treaty in 1925 that acknowledges each state’s right in Arctic research. International law thus is the PRC’s foundation to participate in the Arctic affairs.

There is, however, a critical problem concerning the PRC’s justification of its rights in the Arctic. It was the government of the Republic of China (ROC) – i.e., what became the West-friendly Taiwan rather than the PRC that joined the Svalbard Treaty. At its birth in 1949, the PRC government denounced the international obligations of China’s preceding governments. In contrast, the ROC government honored the international treaties that the Chinese Imperial government had signed when it came into being in 1912. The PRC thus voluntarily gave up its entitled rights in the Arctic at its birth. Moreover, the PRC committed itself to anti-West revolutionary wars for 20 years, even disregarding the Soviet Union’s advice of caution. The PRC did not try to work with the West until the late 1970s. By then, the PRC leaders were facing a Soviet military threat and a financial crisis. Through forming a de facto alliance with the West, the PRC under Deng’s leadership could not only ignore the Soviet military menace but also overcome its financial crisis. When the West opened its markets to the PRC, Deng started his market-oriented reforms.

During the process, the PRC leaders came to know the United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and learned that China was entitled to some maritime rights and could benefit tremendously from international collaboration.6 Among the earliest benefits was China’s successful Antarctic program in the mid-1980s.7 Another benefit was controlling some atolls in the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea in 1988. China conducted this operation in the name of implementing a resolution of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to build a few observation stations in the South China Sea. The operation led to a China-Vietnam naval skirmish in March 1988.8 It foreshadowed the current escalated tension in the South China Sea and reflected the PRC’s pragmatic attitude toward international law. When the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague (PCA) concluded in July 2016 that a China-controlled shoal in the Spratly Islands belongs to the Philippines, the spokesman of the Chinese Foreign Ministry termed the arbitration decision a “piece of waste paper.”9 Although compliance with PCA rulings is voluntary, it goes without saying that China’s attitude toward the PCA’s arbitration raised suspicion over its sincerity about international law on which its Arctic policy is founded.

Nationalism and the Legitimacy of the CCP’s Rule

The PRC’s pragmatic use of international law in the Arctic and the South China Sea comes from its attempt to preserve the CCP’s legitimacy to rule China, a constant challenge that it has faced since its birth in 1921 in its rivalry against Chinese Nationalists. The CCP was a creation of the Soviet Union’s efforts to export its Bolshevik revolution through the Communist International (Comintern) association (1919-1943). Communism therefore became the basis of the CCP’s legitimacy. Moscow convinced the leaders of the influential Nationalists, who were determined to unify the country, to form a coalition with the CCP in exchange for Moscow’s military and financial assistance. The CCP then exploited the Nationalists’ efforts of national unification, and the outcome was the First Nationalist-CCP war (1927-1937). Japan’s invasion of China saved the CCP from destruction. During China’s war of resistance (1937-1945), the CCP followed Moscow’s instruction and accepted the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist government. After Japan surrendered, the CCP refused to put its army under the Nationalist government’s command. The Second Nationalist-CCP war (or the Chinese civil war) (1946-1949) thus broke out. With Moscow’s limited but essential covert military assistance, the CCP defeated the Nationalists and drove them to the island of Taiwan in 1949. The CCP’s victory strongly encouraged its North Korean comrades and triggered the Korean War in 1950. As a part of its efforts to stop communist aggression worldwide, the United States sent its navy to patrol in the Taiwan Strait. The Republic of China therefore survives in Taiwan.

Taiwan forms a constant challenge to the CCP’s legitimacy to rule China. Nationalism and national unification formed the basis of the Nationalists’ legitimacy. The CCP’s foundation was social justice based on communism, although it also shared the goal of nationalism and unification. After it took over China, to maintain its legitimacy, the CCP had to outperform the Nationalists domestically and internationally. Mao Zedong, the PRC’s founder, therefore, was determined to industrialize China and show off China’s strength. And one of the show-offs was an Antarctic exploration that was proposed for the first time in 1964.10 But the PRC did not have the necessary resources following Mao’s programs of industrialization that cost over 30 million people’s lives in three years, and threw the country into turmoil. Exploration was thus delayed until 1984, five years after Deng started his economic reforms and led China back to the West-led international community.

The PRC’s Antarctic program was based on international collaboration. With many countries’ assistance, China built up its first Antarctic station in 1984 and obtained valuable experience in polar research. China’s Arctic program was a post-Cold War extension of its Antarctic program. The end of the Cold War fundamentally reduced the Arctic’s value in national defense. At the same time, Soviet Arctic technologies, including a half-finished ice- strengthened freighter which China converted into an icebreaker, became accessible to China. The State Oceanic Administration (SOA), which was in charge of the PRC’s maritime affairs, seized the opportunity and started China’s Arctic program in the mid-1990s.11 When it became clear that the Arctic sea ice was melting, a situation that would bring profound changes to the geopolitical posture in the northern hemisphere, Beijing found itself, in the mid-2000s, in a position to have its voice heard in Arctic affairs.

The sudden conclusion of the Cold War turned the issues of Taiwan and South China Sea into critical threats to the PRC. Global attention was no longer focused on the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union, and China had quietly become an economic power that relied heavily on imports and exports traveling by sea. Taiwan was on track toward de jure independence while the South China Sea countries consolidated their control over the atolls and shoals that China claimed as its territory. The two issues of China’s territorial integrity and national unification became a focus in Beijing. Thanks to its alliance with the United States, the naval force of the Nationalists in Taiwan was a powerful force in East Asia. But Taiwan’s naval forces had to concentrate their resources on the defence of Taiwan against the CCP. Mao ignored the South China Sea until oil deposits were discovered in its seabed in the early 1970s. Before Mao took any action, other South China Sea countries had controlled a number of disputed atolls and shoals in the Spratly Islands. The question of how to improve China’s position in the territorial disputes thus became urgent.

In order to dominate the South China Sea and to deter Taiwan from independence, the PRC developed a maritime-oriented military strategy in 1992.12 The outcome of the implementation of this strategy has been the development of China’s naval and air superiority in the South China Sea. Nevertheless, instead of a sense of security, a number of PRC’s military strategists found their country falling into a security dilemma. Although China’s booming economy could afford to build a modern navy, it was dependent on overseas trade and the shipping through Malacca Strait. But China cannot control the Malacca Strait without defeating the U.S. Navy and winning a major war against the United States. The more powerful the Chinese navy grows, the more uneasy the situation in the South China Sea becomes and the less secure the PRC leaders feel. As China’s maritime-oriented military strategy was guiding the country to nowhere, the prospect of a commercially beneficial Northern Route became an option for China to go around the southern impasse.

China’s Arctic Strategy and Its Potential Impacts on Canada

China’s commitment to Arctic affairs is rooted in China’s economy. Beneath the high-toned sentences in the white paper outlining China’s Arctic policy, are the shrewd geostrategic considerations and well-developed plans that have been in existence for over 15 years. As early as the mid-2000s, Chinese engineers started designing high ice class merchant ships.” In August 2018, at least two Chinese high ice class merchant ships were in commercial operations in the Arctic. China’s shipbuilding industry is therefore ready for Arctic shipping. In the meantime, the SOA implemented a comprehensive research program on the history, politics, economy, and society of the Arctic countries.14 The implementation of the program helped PRC governmental agencies and academia achieve a consensus on China’s Arctic strategy. Although the consensus has not been explicitly articulated, its principal contents can easily be identified in the publications open to the public. In addition to the principles of international collaboration, international law and contributions to Arctic research and the well-being of Arctic countries, which are addressed in the white paper, Russia-China partnership and mediation of the difference among Arctic countries are among the key components in the consensus.

China and Russia formed a quasi-alliance after the Cold War due to their geostrategic need to counterbalance the United States and its allies. Their bilateral history, however, has not been without difficulties, and currently Russia is concerned about the security of Siberia and China’s growing influence in Central Asia. The Arctic Route is the best approach to consolidating Russo-China relations without touching these sensitive issues. Collaboration with Russia is thus essential in China’s Arctic strategy. With Russia’s consent, even support, China could use its financial and economic strength to mediate controversies among Arctic countries and gradually alter its current status within the Arctic Council.

Chinese participation in the Arctic has several interesting potential benefits for China. For example, China could use Canada’s argument that the Northwest Passage is historic internal waters, to argue that the South China Sea is also historic internal waters of China. This would be a pragmatic use of Canada’s legal arguments to counter criticism of Chinese actions.

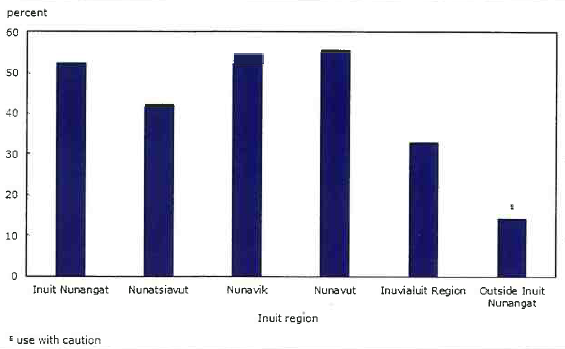

As well, in addition to studying the various current and potential controversies among Arctic countries, Chinese researchers also studied the internal challenges of the Arctic states, especially the deplorable history of indigenous peoples within the Arctic Circle. A number of works on Arctic indigenous societies have been published. Among the works is a monograph on Canada. Pan Min, the author, examined the relations between the aboriginal communities and the provincial and federal governments.15 She discussed the socioeconomic disparities between the Arctic and south Canada. She suggested that the PRC government should adopt a strategy of ‘wait-and- see’ about the indigenous issues while increasing investment in the indigenous areas.

It goes without saying that Pan’s suggestion was based on the PRC’s interests rather than the well-being of the Canadian indigenous peoples. In the context of the PRC’s post-Cold War strategic dilemma and the opportunities to be developed out of the melting of the Arctic sea ice, Pan’s suggestion shows that the PRC leaders have been searching for the weak and exploitable points of the Arctic countries. And they have identified the issue of indigenous peoples. It is the same issue that PRC diplomats in Australia have directly threatened to use if necessary.16 Fortunately for Canada, China’s current interests in the Arctic are around the Northern Sea Route rather than the Northwest Passage. Unfortunately for Canada, the PRC has little stake in Arctic Canada. This implies that the PRC could use indigenous issues in the Arctic to rebuke or embarrass the Canadian federal government when it feels unhappy with Canada’s criticisms or wants to divert public attention (domestic or international) away from China. The Arctic indigenous issue is thus leverage for the PRC to restrain the Canadian government’s freedom of movement.

China’s challenges to the U.S. Navy in the South China Sea have taken numerous forms short of violent conflict. Here, China’s maritime militia interfere with the American naval research ship USNS Impeccable’s towed-sonar array south of Hainan Island in March 2009. Neither wishing to fight an actual war nor able to discourage the United States from operating in the South China Sea, China is increasingly interested in using Arctic waters for its maritime trade.

Conclusion

The PRC has committed itself to Arctic affairs. The origin of its polar policy was Chinese nationalism that led to its Antarctic exploration program. And its commitment to the Arctic comes, in part, from China’s maritime security dilemma over the issues of Taiwan and the South China Sea, and relates to maintaining the CCP’s legitimacy to rule China. As well, the PRC’s commitment to the Arctic is intended to consolidate China’s relations with Russia in order to reduce Russia’s concern over the security of Siberia and China’s growing influence in Central Asia. Canada’s position in China’s geostrategic plan and Arctic strategy is marginal but Canada’s peripheral position might make it an easy target for China to exploit. And the issue of Arctic indigenous people appears to be the issue that China could use to mute Canadian government criticism, divert China’s domestic attention, or use in exchange for agreement about issues somewhere else. China’s Arctic policy therefore could form an indirect and long-term threat to the security of Canada’s Arctic.

Dr. Sheman X. Lai, a PhD graduate at Queen’s University (2008) and MA graduate of War Studies at Royal Military College (RMC) (2002), is an Adjunct Assistant Professor with the History Department, Queen’s University, and Department of Political Science, Royal Military College of Canada.

Notes

- Zhao Ningning, “China and the Paradigm of the Arctic Governance” (translated title), Socialism Studies, No. 2 (2018), pp. 133-140.

- “Vice President Mike Pence’s Remarks on the Administration’s Policy Towards China,” Hudson Institute, Washington, DC, 4 October 2018, available at www.hudson.org/events/1610-vice-president-mike-pence-s- remarks-on-the-administration-s-policy-towards-chinal02018.

- See the State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s Arctic Policy,” English version, January 2018, available at http://eng- lish.gov.cn/archive/white_ paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm,

- Ibid, Section 1.

- Ibid.

- Dumitulu Majilu, “Exclusive Economic Zones” (translated by Liu Nanlai), Global Law Review, No. 6 (1980), pp. 42-64; Mololianyoufu, “On the New Phase of the International Law of the Seas” (translated by Liu Nanlai), Global Law Review, No. 1 (1979), pp. 60-67; IK. Kolosovsky, “The Signifi- cance of the UNCLOS and the Approaches to Obtaining Worldwide Sup- ports for it” (translated title), Global Law Review, No. 4 (1990), pp. 51-54.

- Hu Lingtai, “Antarctic Exploration and Research” (translated title), in Center for Scientific and Technological Information of State Oceanic Ad- ministration (ed.), China Ocean Yearbook, 1986 (Beijing: Haiyang Chu- banshe, 1988), p. 457.

- Liu Huaging, Liu Huaging’s Memoir Chubanshe, 2004), pp. 539-540,

- Chua Chin Leng, “What is the Permanent Court of Arbitration?” China Daily, 14 July 2016 available at www.chinadaily.com.cn/opin- ion/2016-07/14/content_26091459,htm.

- Xie Zichu, “Zhu Kezhen: The Pioneer of China’s Polar Studies” (translated title), in Wu Chuanjun and Shi Yafeng (eds), A Collection of Memories of China’s Geography of Ninety Years (Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe, 1999), p. 29. (translated title) (Beijing: Jiefangjun

- Sheng Aimin, “The Preparations for the Arctic Exploration” (translated title), in China NGO Research (translated title), No. 7 (1994), pp. 17-18.

- Sherman Xiaogang Lai, “China’s Post-Cold War Challenges and the Birth of its Current Military Strategy,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4 (2016), pp. 182-209.

- Zhang Dongjiang, “Analysis of Arctic Marine Shipping and Research on Arctic Ship General Performance” (translated title), MA Dissertation, Harbin Engineering University, March 2012.

- Li Zhen-fu, “Analysis of China’s Strategy on Arctic Route” (translated title), China’s Soft Sciences, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-7; Li Zhen-fu, “China’s Opportunities and Challenges from the Arctic Route” (translated title), Journal of Port and Waterway Engineering, No. 8 (Serial No. 430) (August 2009), pp. 7-15; Li Zhen-fu, “The Dynamics of the Arctic Route in Geo- politics” (translated title), Inner Mongolia Social Sciences, Vol. 32, No. 1 (2011), pp. 13-18.

- Pan Min, Researching Arctic Indigenous People (translated title) (Beijing: Shishi Chubanshe, 2012), p. 314.

- Clive Hamilton, Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia (Mel- bourne: Hardie Grant Books, 2018), p. 280.

Featured Image: China’s research icebreaker Xuelong arrives at the roadstead off the Zhongshan station in Antarctica, Dec. 1, 2018. The research team has carried out unloading work by using the helicopter. Xuelong carrying a research team set sail from Shanghai on Nov. 2, beginning the country’s 35th Antarctic expedition. (Xinhua/Liu Shiping)