By Captain R. Robinson (Robby) Harris, USN (ret.)

Introduction

In his November 1997 Proceedings article, Admiral Jay Johnson, the Chief of Naval Operations, reflected on the landmark white papers …From the Sea, Forward…From the Sea, and the Navy Operating Concept and opined, “…the purpose of the United States Navy is to influence, directly and decisively, events ashore…from the sea, anywhere, and anytime.”1 Scratch nearly any thoughtful naval officer and one finds an intuitive belief that naval forces, particularly forward present naval forces, possess the capability to affect events ashore, indeed even to deter actions by other nations. But how does the ability to influence events ashore really work? What is the theoretical underpinning? Such questions normally leave us mumbling platitudes and surveying the dust on our shoes. This paper is intended to begin to build a theoretical understanding of influence, particularly how forward present naval forces influence events and actors ashore.

Why a Theory of Influence

Before considering “how” forward present naval forces support and foster U.S. influence, first, let us briefly consider why a theory of influence is necessary in the first place. Who needs it?

First, a theory helps us understand patterns of behavior. It helps us explain why events occurred in the past in a particular way, and a theory also serves as an aid in predicting future events. This does not mean that a theory will enable us to predict with perfect clairvoyance events of the future. What theory can do, however, is to allow us to “…trace the different tendencies which are inherent in the situation and to point out the different conditions which make it more likely for one tendency to prevail than for another, and, finally, assess the probabilities for the different conditions and tendencies to prevail in actuality.”2 The role of theory, then, is not just to account for the past or to explain the present but to provide a preview of what is to come. A theory of influence may be beneficial in helping us understand how nations have influenced each other in the past and to predict how influence may be accomplished in the future. Lastly, understanding how nations influence each other may help us deal with the issue of forward naval presence and how carrier strike groups and amphibious ready groups affect influence.

A Definition of Influence

In the foreign policy arena, influence is an index of state power. Regarding power, it is often said that power is to foreign policy experts and practitioners what money is to economists: the medium via which transactions between states are measured and observed.3 Power, however, is a useful concept only in its relative sense. That is, absolute measures of military strength, gross domestic product, technological advancement, and others are helpful, but provide an incomplete gauge of power. Power cannot be adequately assessed until it is employed, and it is employed by nations engaged in the process of attempting to influence each other. Until one state attempts to influence another, we have no useful measure of power. Accordingly, the following definition is offered: influence is the ability of one state to secure a decision and/or an action or inaction by another state consistent with the former’s desires.4

Characteristics of Influence

Although not all inclusive, there are some important characteristics of influence.

All influence attempts are future-oriented. It is impossible to influence the past. Nor is it possible to influence the present unless a decision was made in the past to do so. Accordingly, all influence attempts are made to affect the anticipated future behavior of another state.

Influence does not necessarily imply a modification of another state’s behavior. There are situations in which one state (the influencee) is currently behaving and/or is predicted to behave as desired by another state (the influencer), but in which the influencer nevertheless attempts to increase the probability of continued favorable behavior. This type of influence activity on the part of the influencer is called reinforcement.5

Inter-nation influence is not dyadic in nature. For analytical or planning purposes, it is convenient to think only of the reciprocal influence of one pair of nations on each other, but clearly the international system is not a dyad. Many nations simultaneously influence many others, either directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally. Intentional or deliberate influence is called direct influence.6 Not only is the system characterized by reciprocity, but by multiple reciprocity.

Purposes of Influence

Having defined influence and reviewed some salient characteristics, let us now consider the purposes for which influence is used. Remembering that all influence is future-oriented, the following proposition is offered: Nations attempt to influence other nations for one of two purposes7 including to modify the anticipated behavior of another nation, and/or to assure or increase the probability of the anticipated behavior of another nation.

One normally thinks of attempts to influence behavior within the context of behavioral modification. That is, one nation predicts that the behavior of another nation will be unfavorable and via various means and with various tools attempts to influence the nation in question to modify the anticipated unfavorable behavior. But as posited above, nations also attempt to influence other nations to assure or to increase the probability that the nation in question will continue to behave favorably.

Influence Objectives

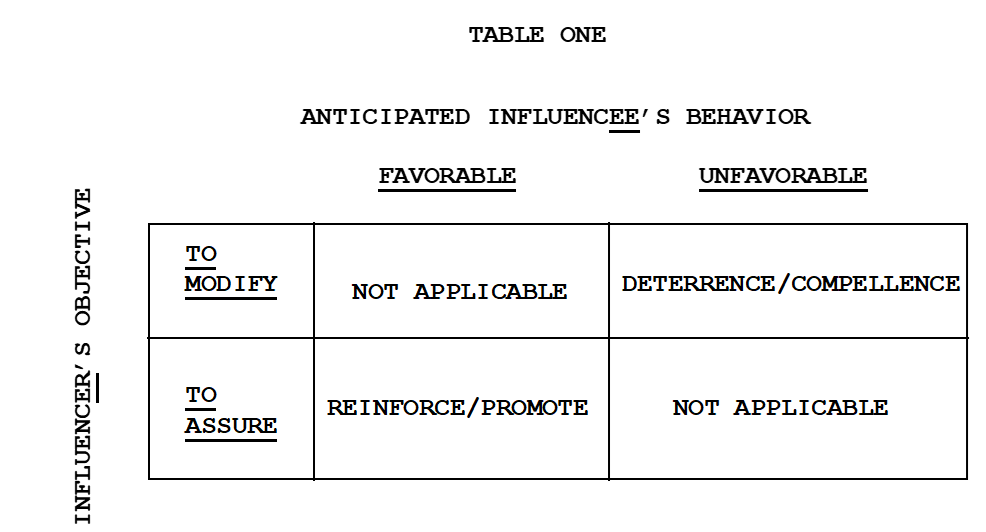

Let us now examine the objectives for which states attempt to modify or maintain/assure the behavior of other states. The following proposition is offered: the objectives for which states attempt to modify or to maintain the behavior of other states are based on the acceptability of the influencee’s predicted behavior. If the predicted behavior is favorable, the influencer will use means to promote or to reinforce the predicted behavior. On the other hand, if the predicted behavior is unfavorable, the influencer’s objective will be to employ means to deter or to compel the other nation. This taxonomy is presented in Table One.

If a nation predicts that another nation will behave favorably, clearly there would be no reason to attempt to modify that behavior. Similarly, if a nation predicts that another nation will behave unfavorably, there would be no reason to attempt to assure that behavior. On the other hand, if another nation’s predicted behavior is unfavorable, the influencer may elect to attempt to modify that behavior by attempting to deter the subject nation from taking a predicted unfavorable course of action. It should be noted that deterrence assumes that the influencee has not yet taken the unfavorable course of action. Compellence, conversely, assumes that the influencee has already taken an unfavorable course of action and must be influenced to rescind or withdraw from its unfavorable action.

If nations could predict with complete accuracy the behavior of other nations, efforts to promote or reinforce predicted favorable behavior would not be necessary. Because of the complexity of the international system and the poverty of intellectual disciplines involved, however, such predictability is not feasible. Accordingly, states attempt to increase the probability of anticipated favorable behavior by promoting behavior which is seen to be proceeding in a favorable direction and attempt to reinforce established favorable behavior.

Some examples of influence efforts to deter, compel, reinforce, and promote may be helpful:

- Deterrence. The role of U.S. and Allied forces in Europe from 1945-1991 was to deter an attack by Soviet/Warsaw Pact forces. Similarly, Sixth Fleet forces in the Mediterranean were present to deter an attack on NATO’s southern flank.

- Compellence. As Desert Shield/Storm coalition forces were mustered in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf from August 1990 through January 1991, threats were made to Saddam Hussein to compel him to withdraw from Kuwait. Because these threats (attempts to influence) were unsuccessful, actual use of force (armed conflict) was required to compel withdrawal.

- Reinforcement. Among other objectives, the presence of U.S. forces in western Europe in the post-Cold War era also serves principally to reassure European allies of continued U.S. interest in European matters and reinforces current European policies favorable to the U.S. The Navy and Marine Corps conduct manifold exercises every year with friends and allies around the world to reinforce positive relations.

- Promotion. In addition to stemming the flow of illegal drugs into the U.S., U.S. engagement in Latin America today serves to promote the evolving change to democratic governments and market driven economies. The presence of the U.S. Seventh Fleet in the Western Pacific promotes and reinforces peaceful relations among the nations of Northeastern and Southeastern Asia.

Techniques of Influence

Relations between nations range from complete consensus on almost all issues (U.S.-U.K.) to total discord on nearly all issues (U.S.-Iran). The amount and type of influence required for the influencer to achieve desired behavior on the part of the influencee varies with the nature of the relationship between two nations and their level of shared interests.

For example, when dealing with the U.K., in many if not most instances, very little if any influence is required for the U.S. to achieve its desires. This is because of the high level of shared interests between the two English-speaking nations. The situation between the U.S. and U.K. is rather like a family situation when a brother approaches his sister to enlist her support in making arrangements to obtain medical care for an ill parent. Because both siblings share a common interest in the health and well-being of the parent, normally no influence is required by the brother to gain the sister’s cooperation – a simple request may be sufficient.

On the other hand, since the 1979 revolution, the U.S. and Iran have shared so few common interests that extraordinary leverage has been required for the U.S. to achieve its desires vis-a-vis Iran and vice versa. These have ranged from crippling economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation to the use of force against Iranian military assets during the Tanker Wars of the 1980s.

Most relations between nations lie somewhere between the U.S.-U.K. and the U.S.-Iran extremes. On those occasions when influence is required, two broad categories of techniques are available to the influencer.

Techniques of Influence

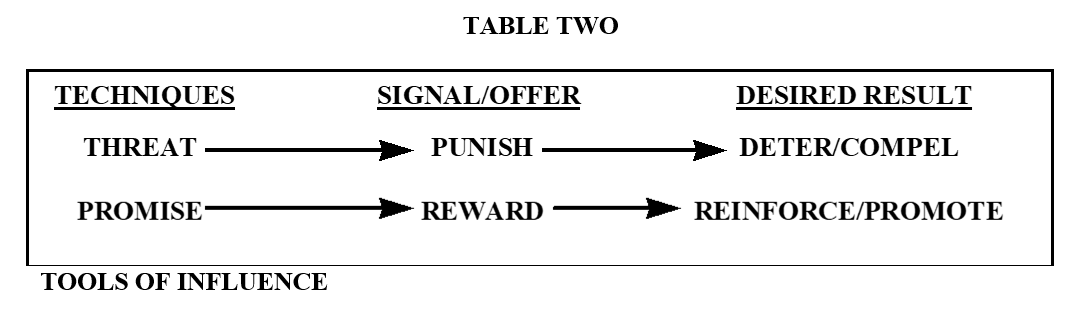

A threat is a communication to the influencee by the influencer that unless the influencee complies with the influencer’s desires, the influencer will act to punish the influencee. A promise is a communication to the influencee by the influencer that if the influencee complies with the influencer’s desires, the influencer will act to reward the influencee. Although not necessarily always the case, in most instances threats are used to deter and to compel and promises are used to reinforce and promote.

Tools of Influence

With respect to the tools of influence, states may use diplomatic, economic, military, and informational tools to punish and to reward targets of influence.

Military tools of influence may be used to achieve military goals as well as political and economic objectives. Similarly, political and economic tools may sometimes be useful in gaining military objectives. For example, a trade embargo or conversely promising most favored nation trade status could be effective in deterring a nation from the sale of weapons of mass destruction. However, as relations between nations worsen, as they share fewer common interests, objectives can become more militarily dominated and defined, thereby causing the effectiveness of military tools of influence to increase.

Consider, for example, ensuring Iran compliance with UN sanctions. Although diplomatic demarches (political tool) and trade sanctions (economic tool) had been employed as threats to influence Iranian behavior, arguably the most effective tool to condition Iran’s actions is the presence of military forces (military tool) on the ground in allied states and naval forces on station in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea. Moreover, because the predominant concern of U.S. allies and friends in Middle East is one of military security (against an assertive Iran) military tools take on disproportionate influence for the U.S. in region.

The Effectiveness of Influence

Having derived a definition of influence, examined its characteristics, the purposes and objectives for which it is used, the techniques employed to achieve it, and the effect of shared interests on the requirements for the use of those techniques, let us now consider what makes influence effective.

Here we must examine the influencee’s decision calculus, and how the influencee weighs a range of outcomes of an influence situation. Two dimensions come into play: utility and probability.8 The degree to which the influencee likes or dislikes the prospect is called utility or disutility. The likelihood that the influencee assigns to the outcomes ever occurring is called probability. The influencee’s combined assessments of these two dimensions determines expectations and thus the influencee’s response to the influence attempt.

Each nation has, either explicitly or implicitly, a continuum from good to bad along which it assesses outcomes of an influence attempt. The continuum is based on values systems and although values systems certainly are not uniform from nation to nation, there is some degree of similarity. Outcomes which tend to restrict a nation’s freedom of action are normally placed low on the utility scale (or high on the disutility scale). Conversely, outcomes which do not restrict freedom of action are placed high on the utility scale (low disutility score).

Nations do not, however, make decisions based solely on the attractiveness or unattractiveness of various potential outcomes. Nations also compare outcomes not only in terms of desirability, but also in terms of estimated likelihood. While some nations are more risk-prone than others, most nations are fairly conservative in foreign policy. They seldom commit resources and prestige to the pursuit of an outcome which seems improbable, regardless of how attractive the outcome may be.

Despite idiosyncrasies along one or the other dimension (utility/probability), nations combine both sets of considerations in responding to an influence attempt. The decision of how to respond to an influence attempt is the result of a utility and probability calculation.

Thus, for an influence attempt to be successful, the influencer must address something that the influencee considers valuable (high utility) and the influencer must persuade the influencee that the influencer will take action as threatened or promised (i.e., the influencer must be perceived as credible). Thus, the utility-probability calculus determines influencee response both to threats (deterrence/compellence) and promises (reinforcement/promotion).

Recent studies suggest that there is another important dimension to credibility, one not based solely on military capability or political will to use military force, but the speed with which military power (influence) can be employed.9 That is, the influencee’s knowledge that the influencer possesses the capability to act without delay seems to be a key component in the influencee’s decision calculus. This, of course, bolsters and helps to explain the argument advanced by the Navy and Marine Corps regarding the special “shaping” (influencing) role of forward present Navy and Marine Corps forces. Their nearly constant presence in the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean/Arabian Gulf, and western Pacific is a visible reminder to friend and foe alike of U. S. intent, capability, and perhaps more importantly, the ability to act swiftly.

Conclusion

So, what does all this discussion of a theory of influence add up to? Hopefully, it will help naval officers better understand what we tend to understand intuitively already: forward present naval forces play a special role in influencing (shaping) other nations.

These forces are able to fulfill both purposes of influence: Assure the continuation of anticipated positive behavior and modify anticipated negative behavior. They are able to achieve both objectives of influence: Promote/reinforce positive behavior, and deter anticipated negative behavior/compel reversal of negative faits accompli. They are able to convey both techniques of influence: promises of rewards for positive behavior and threats of punishment for negative behavior. They are able to affect the influencee’s decision calculus of utility and probability. Their diversity and breadth (from F-35s and F/A-18s, from LRASMs to Tomahawks, and to a Marine rifle company squad) and reach (to a thousand miles) permits them to reach out and touch something that matters (high utility) and their combat readiness gives them high credibility/probability of successful employment.

Being there counts. The ability to act without delay during the early days of a crisis or a potential crisis affects the influencee’s initial decision calculus in a special way. It precludes an opponent an early and easy fait accompli. It forces a rational opponent (influencee) to carefully evaluate carefully their courses of action. It tends to preclude impulsive behavior. It forces the influencee to conduct a utility/probability calculation. It buys us time to augment U. S. forces, if necessary. It gives us timely influence. And, at the end of the day, if the influence attempt is not timely, it is far less effective. Here in their forward presence lies the unique influence advantage of naval forces.

Captain Harris commanded USS Conolly (DD-979) and Destroyer Squadron 32. Ashore he served as Executive Director of the CNO Executive Panel. He was a CNO Fellow in CNO Strategic Studies Group XII. It was during his stint as a CNO SSG Fellow that this article was first begun. Captain Harris is indebted to Mr. Dmitry Filipoff for his efforts in updating the draft, sharping the arguments, and greatly improving the readability.

References

1. Proceedings, U. S. Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland, November, 1997.

2. Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace (New York, Knopf, 1948), pp. 6-7.

3. This discussion of power is drawn from J. David Singer, “Inter-Nation Influence: A Formal Model,” American Political Science Review, 17, 1963.

4. This papers examines the use of forward presence as an instrument of US influence and, therefore, focuses on those actions taken prior to the actual use of force, i.e., armed conflict.

5. The term “reinforcement” is taken from Singer, Ibid.

6. Intentional or deliberate influence is called DIRECT influence. Unintentional influence is here labeled INDIRECT influence.

7. See Barry Blechman and Stephen Kaplan, Force Without War, Brookings, 1978, pp. 70-78.

8. The utility-probability concept is drawn from Singer, op. cit., pp. 424-426.

9. See, for example, Dr. Edward Rhodes, “Conventional Deterrence: Reivew of Empirical Literature unpublished paper for the Department of the Navy (N3/5) 1997.

Featured Image: Off the coast of Hawaii on 20 June 2000, the Abraham Lincoln Battle Group steams alongside one another for a Battle Group Photo during RIMPAC 2000. Ships involved are Tucson (SSN-770) & Cheyenne (SSN-773), Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72), Shiloh (CG-67), Bunker Hill (CG-52), Fletcher (DD-992), Paul Hamilton (DDG-60), Cromlin (FFG-37) and Camden (AOE-2). (USN photo by PH2 Gabriel Wilson)