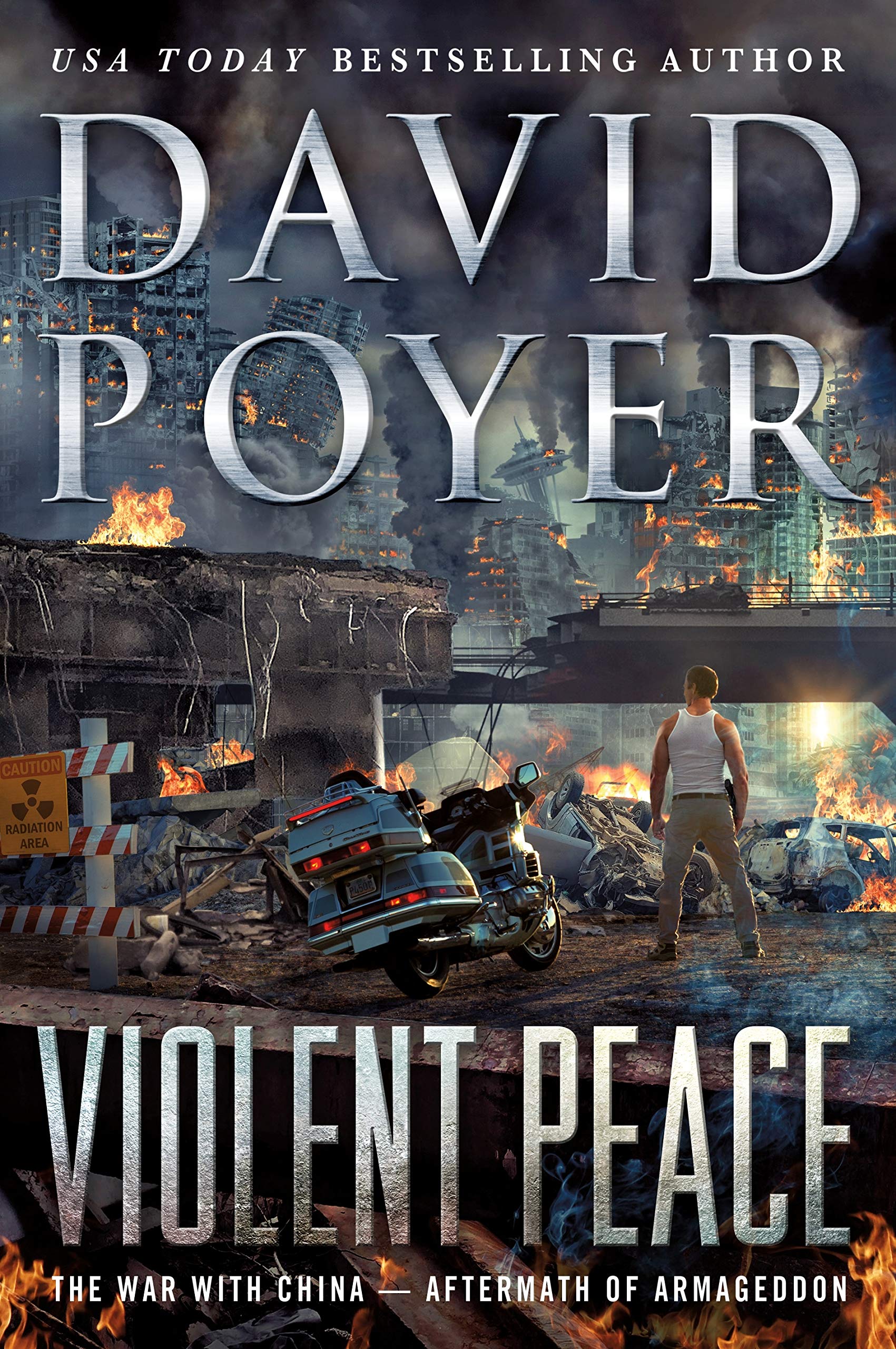

David Poyer, Violent Peace: The War with China: Aftermath of Armageddon, St. Martin’s Press, 2020, $27.99/hardcover.

By Mike DeBoer

David Poyer’s latest book, Violent Peace (to be released December 8, 2020), is the author’s most sobering work to date. This latest edition to the Dan Lenson Tales of the Modern Navy series finds the United States in the midst of armistice negotiations after a devastating conflict with China. The U.S. is also grappling with domestic unrest and uncertainty against the backdrop of depopulated cities, rampant militias, and nuclear fallout. In short, Poyer’s near-future America bears little resemblance to the 1980s-era prosperity and hegemony fans of the series will remember from The Circle. Though the trajectory of the series has been toward entropy, particularly since 2015’s Tipping Point, Violent Peace presents readers with a new depth of pessimism and despair.

Protagonist Dan Lenson’s daughter has gone missing while attempting to distribute influenza vaccines. (One has to wonder if Poyer retains some Nostradamus-like abilities in that he seemingly predicted a pandemic virus with its origin in China in previous works.) In a subplot with echoes of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Lenson, now on leave after his victory in the South China Sea, attempts to find her in a dystopian ride across America, confronting murderous militias, high background radiation, ghost towns, and the detritus of an unrecognizable American heartland.

Fans of the series will find their favorite characters similarly vexed. Unaware of her husband Dan’s search, Blair continues final negotiations with China, harboring great misgivings about the future implications of harsh peace. Dan’s former Executive Officer, Captain Cheryl Staurulakis, now in command of a small surface group, confronts a predatory Russian surface group with her inferior force in the Sea of Japan. Teddy Oberg, the former SEAL and escapee from a Chinese prisoner of war camp, rejects his previous convictions as a result of an religious encounter at high altitude, electing instead to conduct his own brand of unrestricted jihad against the Chinese rulers of Xinjiang province. Marine Corps infantryman Hektor Ramos, injured badly in his assault on Hainan Island, returns to his home and an ungrateful nation, a devastated economy, and few job prospects.

Violent Peace is a solemn book. In the narrative arc of Poyer’s War with China subseries, Peace displays a depth of pessimism that some readers may find overwhelming. If combat is ultimately a test of human will, it follows that war is a test of national will, and an exhausted, divided America is at the precipice of losing its way. Poyer’s latest illustrates just how dire a destination such a path promises. Peace’s United States is slipping toward one-party rule, even as open revolts occur in the South and Central U.S. Impoverished by the war, the nation has scarce funds to train or employ its veterans, further paupered by the large military forces it had previously created. Forced outwardly to validate such sacrifice to the American people, the administration forces a humbling peace on the Chinese, guaranteed, like Versailles, to instigate national fury and further reckoning.

Poyer’s thesis throughout the series holds, that war with China is closer and more terrible than most would believe. In fact, at one point in the story, Blair, typically the most cerebral character and perhaps somewhat of an author surrogate in her views, states that she believed the outcome inevitable. Indeed, it was the natural outcome of the fear, honor, and interest of rising and established powers as the globe reorders. In Violent Peace, Poyer emphasizes the human costs of such a conflict domestically and to dramatic effect. Insulated from foreign policy’s nastier side effects by its bordering oceans for most of their existence, the U.S. population has so infrequently dealt with the hard hand of great power conflict that they have perhaps assumed immunity. In Peace, readers can glimpse the consequence of such an assumption given a modern, great power conflict with a rising China.

Poyer is at his best when he captures the zeitgeist, and in Violent Peace, the author is undeniably on top of his game. Poyer seems to have pulled from the history of Civil War Reconstruction, modern American political turmoil, and married them with the physical and physiological effects of American nuclear strikes in 1945 to create a picture of the devastation that awaits both parties following nuclear war. He captures and magnifies current American political chaos and divisiveness tearing at the connective tissue of American society ably and affectingly. Peace’s near-future United States is far from united – Poyer’s carefully drawn caricatures of the darker factions of contemporary American society give readers plenty to consider. Pitted against an overgrown security state, with violent, paramilitary federal troops, these factions wage a bloody, protracted campaign. Poyer’s message is effective – internal strife is on par with external factors in terms of destructiveness.

One aspect on which the book might have expanded is the intelligence community’s role. For all his very in-depth thought about future war at sea, Poyer did not describe a similar revolution in how the CIA might run covert action in tomorrow’s conflicts. Instead, his CIA Covert Action Team member uses better drones and in-person meetings, vice any new or transformative technologies. In an area where biotechnology is in its infancy, human tracking is improving dramatically, compression software is improving every hour, and lethal technologies abound, it seemed a little regressive to have a case officer riding a donkey, and visiting a Predator control van in a dust-blown portion of the world. Selective viruses targeting individual DNA, messages left in microprint, drone-delivered arms – all could potentially influence covert action, perhaps the topic of Poyer’s next work.

Readers who enjoy the technical accuracy of Poyer’s books will still find carefully painstakingly rendered naval combat, but Violent Peace is ultimately a national and human tale, focused less on the practical aspects of war than the less tangible costs on individuals and societies. Indeed, Poyer’s trademark fidelity only serves to amplify the greater thesis of Violent Peace – the current level of divisiveness in the United States may not, or perhaps will not, meet first contact with the cataclysm of China. The best of Poyer’s writing borrows from contemporary experience and Violent Peace is no exception. This book is highly recommended to fans of the series and students of modern conflict alike, although it is best enjoyed in the context of the complete narrative arc of the War With China subseries.

Michael DeBoer is a naval officer.

Featured Image: A unitary medium-range ballistic missile target launches from the Pacific missile range facility and flies northwest toward a broad ocean area of the Pacific Ocean. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Mathew J. Diendorf/Released)

Climate and consequences may engage more priorities internationaly (including China) than going to war. Cooperation because of major disasters of many kinds (resources; ecology) may force hitherto enemies to request help from any source. People world-wide are becoming less interested in Defence and war because of the Coronavirus and the fact that ecosytsems are changing the food-sources we have. That is likely to alter thinking not only in the civilian world but militarily as well.

Just an hypothesis, because there is no certainty and that, of course, promotes the opposite views.