Regional Strategies Topic Week

By Viet Hung Nguyen Cao

The new U.S. South China Sea policy, recently announced by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, once again put the disputes between China and other claimants in this Westernmost area of the Pacific back into the limelight. The core component of the disputes is China’s nine-dash line claim which overlaps with the existing maritime zones of several countries in the region. In recent years, China has deployed grey zone tactics, such as utilizing micro-aggressive measures such as maritime militia and the deployment of survey vessels to enforce its claims.

Vietnam, as one of the major claimants involved, has been a frequent target of these tactics. With only weak, symbolic reactions to China’s aggression, Vietnam is without a proactive or effective strategy to fight back. There are policies that Vietnam should adopt, but at the heart of these policies is the need for more international cooperation in resolving the issues linked to China’s strategy.

China’s Tactics

A primary component of China’s tactics in the South China Sea is the use of maritime militia and law enforcement vessels to intimidate fishermen and drive them away from traditional fishing areas. Annually, China announces a fishing ban, claiming that its purpose is to preserve the fish stock in the South China Sea. Empowered with this ban, Chinese vessels frequently harass, attack, and sink Vietnamese vessels. The most recent case occurred in June 2020, when a Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) cutter and motorboat surrounded a Vietnamese fishing boat and rammed the vessel. The Vietnamese fishermen were then captured, beaten, and were forced to sign documents stating that they had violated the fishing ban. The CCG also took away the fishing equipment and caused damage to the ship.

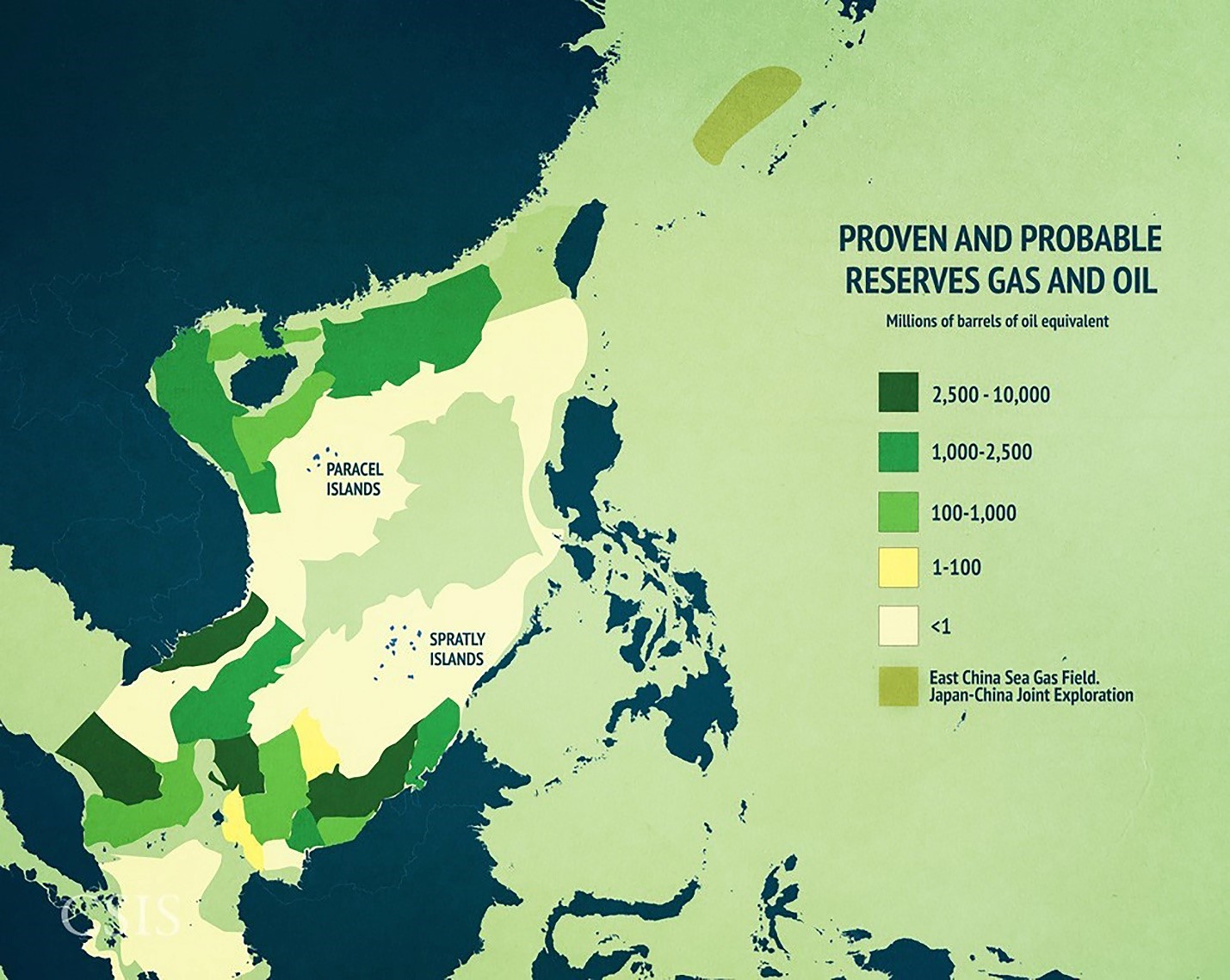

China’s tactics in the SCS also feature the use of research vessels and their escort fleets to harass gas and oil development activities of other claimants, forcing them to reconsider or abandon their projects. China often deploys several survey vessels, as well as an escort fleet of law enforcement vessels and maritime militia, to planned oil and gas blocks of claimant states in order to deny other claimants access to these waters. Notable cases include the Vanguard Bank standoff from July to October 2019, as well as the recent appearance of Chinese research vessel Haiyang Dizhi 4 inside Vietnam’s EEZ near bloc 6.01, a gas bloc where Vietnam was planning to jointly explore with Russian gas conglomerate Rosneft.

These tactics clearly show China’s ambitions to establish a permanent maritime presence in the region. China aims to use these tactics as a means to enforce its excessive maritime claims and force Southeast Asian countries to accept China as the new hegemon.

Vietnam’s Efforts

Faced with these challenges, what has the Vietnamese government done to protect its sovereignty and maritime rights? The answer is, on paper, a lot, but their actions thus far have been lackluster and ineffective. Vietnam’s primary response to Chinese aggression has been through diplomatic protests and public statements.

Vietnam’s diplomatic protests against these actions are often conducted at the bilateral level, such as through meetings or teleconferences between foreign affairs officials, both at government and party levels. Most recently, after the aforementioned incident in June, Vietnam’s Foreign Minister held a teleconference with his Chinese counterpart to discuss solutions. Similar lines of communication have been effective in preventing conflict escalation, thus mitigating a potential diplomatic crisis or an all-out war. Yet, these protests have been unable to reverse Chinese actions.

In their public statements, Vietnam demonstrates a firmness regarding the sovereignty of Vietnam, as well as a willingness to cooperate to resolve the dispute according to international law, especially the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). However, the repetition of these phrases through the years have turned these statements into meaningless pronouncements, and the messages in these statements have even become memes, used in a mocking attitude by Vietnamese netizens. In recent years, these statements have begun to include mentions of litigation as a possible means of resolving the disputes, suggesting Vietnam’s willingness to bring China to court. However, a threat is only credible when those making the threat are willing to walk the talk. Without concrete action to signal serious intent, the threat of bringing China to court will become meaningless over time.

Vietnam has suffered the consequences for its weak and symbolic reactions to China’s aggression in both the political and economic fields. The most notable setback to Vietnam was how China increased the frequency of its activities in recent years. After the 2014 Haiyang Shiyou 981 standoff, China had repeatedly deployed research vessels and oil rigs to the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Vietnam, and generally with longer duration and increased frequency of missions. In 2014, China only deployed its vessels into Vietnam’s EEZ once, and only for about two months. Then last year, it deployed the vessel four or five times, with the total duration of these missions being around six months, from late March until early October. In the whole of 2019, there were three cases of Chinese vessels attacking and/or harassing Vietnamese fishing vessels. This year, three cases have occurred in just the first six months.

With China showing little tolerance for vessels violating their arbitrary fishing ban, many Vietnamese fishermen are being forced to abandon their traditional fishing grounds and sail further south. This is a root cause for increasing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities in the region. These fishing vessels intrude into the waters of Indonesia and Malaysia and conduct illegal fishing. This has created a wedge issue in the relations between Vietnam and both countries as more and more Vietnamese fishing vessels are being detained and in some cases, destroyed. Most recently, a clash between Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency vessels and Vietnamese fishing vessels operating illegally inside Malaysian waters resulted in the death of a Vietnamese fisherman.

Aside from an international level, there is a possibility that Vietnam is also facing political consequences at home. With the increased harassment of China, Vietnam has had to cancel several oil and gas development projects, with the compensation for foreign companies totaling close to $1 billion. Most recently, Vietnam delayed the exploration of block 06-01 until next year, a project previously rumored to be cancelled altogether. Aside from this, there have been reports of grassroots dissatisfaction of Vietnamese fishermen whose vessels were sunk. According to one researcher, they expressed disappointment that their cases were not appropriately handled by the Vietnamese authorities, and their loss was not compensated sufficiently. If this situation continues, the Vietnamese government might face challenges to its legitimacy and lose domestic support.

Policy Recommendations

In order to resolve these issues, Vietnam should consider alternative policies, alongside existing ones, to both manage the situation in the meantime, as well as solving issues in the long run. The first step is to expand its current international cooperation on increasing maritime domain awareness. Potential measures include providing fishing vessels with radio and tracking equipment, with updated Geographical Information System (GIS) signals. Vietnam should also negotiate with countries in the region, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, on protocols in situations where local authorities capture Vietnamese fishing vessels operating in their EEZs, as well as for unexpected encounters at seas. By mitigating possible consequences of IUU fishing, Vietnam can avoid regional tensions and domestic backlashes.

Secondly, Vietnam should also consider the possibility of initiating joint patrol operations along with the coast guards of other states. Considering how Chinese fishing bans and maritime militia are also affecting Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines as well, these countries should consider coordinating patrol activities in the South China Sea, as well as improving their information sharing systems in order to minimize the impact of China’s actions. The joint patrols will help in driving out Chinese maritime militia operating in the waters, as well as managing IUU fishing.

An alternative policy to consider is to organize Vietnam’s fishing vessels into fleets. In past incidents, the vessels that were sunk by Chinese vessels were operating alone and far from other ships. With the establishment of the fishing fleets, the vessels will be better protected against Chinese aggression, and in the case of an attack, the vessels will be able to help one another, minimizing the damage to the ship and the loss of personnel.

Last but not least, Vietnam should take actions regarding its threat to file a case against China, making the threat more credible. While the recent move of nominating arbitrators to Annex VII of UNCLOS indicated Vietnam’s intention of using this mechanism, it might also be better to look into other options as well, such as The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS). In order to signal its intention, Vietnam should raise concerns regarding Chinese nominations for ITLOS judges. As recently pointed out, China’s nominations had been elected uncontested since 1996. Opposition from Vietnam would show serious commitment to upholding international legal values, and demonstrate serious consideration of resolving the disputes through legal means.

Conclusion

China’s strategy in the South China Sea has brought significant challenges to Vietnam, and the government’s weak and symbolic responses have only worsened the situation. In order to manage these issues, Vietnam needs to address these challenges individually, yet they cannot be fully addressed without cooperating with other states. Vietnam alone is not an economically, diplomatically, nor military sufficient contender against China, but through cooperation with others, Vietnam can exert significant influence to change the status quo and turn the tables in its favor.

Viet Hung Nguyen Cao is an MA student at the Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University, and a Research Assistant at the South China Sea Data Initiative. His primary research interests are the maritime disputes in East Asia and Japanese politics.

Featured Image: A Vietnamese Coast Guard ship (second right, dark blue) tries to make way amongst several China Coast Guard ships near a Chinese drilling oil rig (right background) being installed in disputed waters in the South China Sea on May 14, 2014. (Photo via Hoang Dinh Nam/AFP/Getty)

Vietnam needs subs

Vietnam is a small fish in a large ocean with big sharks. It has nowhere to turn to for reliable allies strong enough to take on China. Vietnam is stuck with its fate and will have to wait for some major change in the paradigm.