By Michael van Ginkel

Introduction

Sprawling archipelagos and limited government resources make comprehensive maritime domain awareness (MDA) challenging in the Sulu and Celebes Seas. To improve their information gathering capabilities, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines have invested in advanced geospatial data acquisition technologies like unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and satellites. Integrating the resulting datasets into existing databases for an aggregate analysis greatly enhances regional MDA. Incorporating geospatial information provides authorities with a deeper understanding of the Sulu and Celebes Seas’ physical environment and how maleficent actors like insurgent groups, human smugglers, and arms traffickers threaten security. These information assets assist law enforcement agencies in prioritizing the deployment of their limited maritime assets and are some of the more critical capabilities in the regional toolkit for ocean governance.

The Sulu and Celebes Seas

The Sulu and Celebes seas are an important geographical area within Southeast Asia. From an international perspective, a significant amount of all commerce traded between Australia and East Asia is shipped through the area. Locally, the seas form a tri-border area heavily used by the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia for littoral trade. The biodiverse marine environment, combined with a significant reliance on fisheries production by littoral countries, also elevates the area’s importance. As pointed out in the Stable Seas: Sulu and Celebes Seas maritime security report, however, the complex political and geographic environment creates substantial difficulties for law enforcement agencies attempting to monitor the Sulu and Celebes Seas for maritime crime. Faced with kidnapping operations of armed militant groups like Abu Sayaff and illegal, unreported, and unregistered fishing violations by both local fishermen and foreign fishing companies, the three littoral countries have begun relying more on advanced geospatial technologies to enhance their maritime domain awareness. The multi-pronged approach to intelligence gathering allows for more informed responses to the wide range of maritime threats present in the region.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

UAVs offer a flexible and cost-effective method of gathering geospatial data. Flying at an altitude of around 400 feet creates high-resolution orthophotography and aerial mapping. Law enforcement agencies also find the UAVs’ ability to provide real-time information and track moving objects highly useful in dealing with dynamic security environments. The countries in this region began developing early versions of UAVs for maritime intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance operations in the early 2000s. Indonesia, for instance, began a government-funded program for UAV development in 2004 in order to monitor nontraditional threats like illegal, unregistered, and unreported fishing, as well as trafficking and smuggling.

As technological advances made it easier to access high-quality UAVs, demand rose accordingly. Most recently, the United States Department of Defense provided Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia with a total of 34 Insitu ScanEagle drones to improve their MDA. Their growing popularity is reflected in the global market for UAVs, which Acumen Research and Consulting estimates will achieve a worth of roughly $48.8 billion by 2026. Collecting geospatial data through UAVs has created the opportunity for agencies to expand surveillance coverage of specific areas of interest indicated in intelligence reporting. Increased geospatial surveillance of the Sulu archipelago, for instance, could corroborate reports of Abu Sayyaf insurgent activity on the islands before troops are mobilized for a ground search.

Satellites

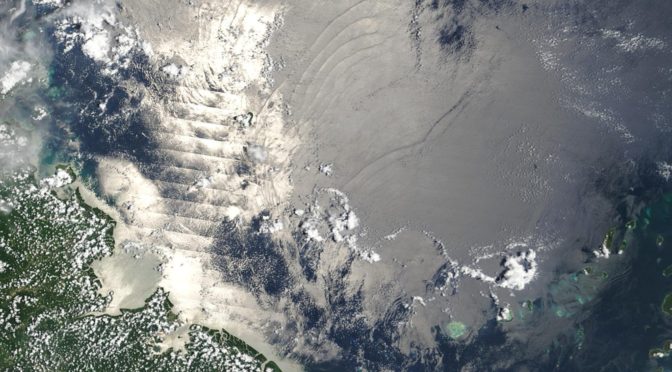

Satellites provide comprehensive coverage of extensive areas on a consistent basis. Satellites have proven to be an asset through their ability to pierce cloud cover and provide regular region-wide updates across the complex terrain of the Sulu and Celebes Seas. The tropical climate and atmospheric conditions of the tri-border area make satellites all the more useful for regional geospatial data collection.

In September 2018, the Philippines signed an agreement for access to data from the NovaSAR-1 satellite. Equipped with a synthetic-aperture radar (SAR), the NovaSAR-1 can systematically identify vessels and aquaculture systems in Philippine waters. SAR datasets have increasingly been used to identify the location of ships based on their outline, which has proven advantageous in tracking vessels that have turned off their Automatic Identification System transponders. Similarly, Indonesia built its indigenous satellite capabilities through the National Institute of Aeronautics and Space (LAPAN). After collaboratively launching the LAPAN-A1 microsatellite with India, Indonesia created and launched the LAPAN-A2 and LAPAN-A3. The earth observation satellites expand the country’s MDA by incorporating AIS and providing video surveillance. The successful use of microsatellites in Indonesia convinced the government to invest in creating an orbital rocket with the capacity to launch a satellite into low Earth orbit by 2040.

Dataset Integration

Systems designed to integrate geospatial datasets into existing databanks allow experts to conduct a holistic analysis. Overlapping means of ship identification through a combination of AIS and low Earth orbit satellites like SAR provides a system of checks and balances. Merging geospatial data with non-sensor data like human and open-source intelligence means all available information can be comprehensively analyzed for threats. Algorithms tapping into artificial intelligence can then predict imminent illegal or illicit maritime activity by observing real-time data trends.

Algorithm parameters and situational context provided by human experts ensure the analysis is issue-specific and generates actionable results. Within the Sulu and Celebes region, for example, traditional migration patterns between Mindanao in the Philippines and Sabah in Malaysia can confound AI attempts to reliably identify human trafficking and drug smuggling without human guidance.

Conclusion

Innovative means of collecting geospatial datasets allow maritime law enforcement agencies to more comprehensively monitor the maritime domain. When integrated with non-sensor forms of intelligence, geospatial information obtained by UAVs and radar can greatly expand regional coverage. The resulting data analysis conducted through artificial intelligence and system experts then informs governments on illicit and illegal activity. Within the Sulu and Celebes seas, geospatial coverage has reduced the strain placed on limited maritime resources. The bird’s-eye view of open waters, archipelagos, and coastlines means Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines can appropriately allocate law enforcement assets to best counter illicit activity. Given the complex security environment of the Sulu and Celebes seas, the ability to make decisions based on reliable intelligence will significantly impact the success rate of law enforcement operations.

Michael van Ginkel works at One Earth Foundation’s Stable Seas program where he researches Indo-Pacific maritime security. His research and publication background focuses primarily on conflict resolution and prevention. Michael graduated with distinction from the University of Glasgow where he received his master’s degree in conflict studies.