By Kyle Cregge

Trent Hone offers a detailed examination of the wartime leadership Admiral Chester Nimitz in his book, Mastering the Art of Command: Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Victory in the Pacific. By studying Nimitz’s talented leadership through the lens of complex adaptive systems and theories of management, Hone introduces new insight into the underlying causes of successful wartime organizational management and strategy-making.

studying Nimitz’s talented leadership through the lens of complex adaptive systems and theories of management, Hone introduces new insight into the underlying causes of successful wartime organizational management and strategy-making.

In this discussion, Hone delves into how Nimitz managed personal relationships, how organizational command structures influenced operations, and how leaders can set the stage for their subordinates to rapidly and meaningfully innovate.

Can you describe where you see the linkages between your previous book Learning War and Mastering the Art of Command? To what extent is this book a “sequel,” if we focus on Nimitz as a central character? How does exploring Nimitz’s leadership within a complex adaptive system help us today?

I think of it less as a sequel and more as a different, but complementary, lens. Learning War focuses on the Navy as a whole, as a large complex adaptive system, and tries to explain how the Navy learned and improved its fighting doctrine. I think that perspective is quite valuable, but I have been told that it can be unempowering, that the role of individuals can be lost when the organization is centered.

With Mastering the Art of Command, I wanted to address that. I wanted to investigate the role individuals play in a broader system, and I thought a good way to do that would be to select a particularly significant individual—Admiral Nimitz—and examine his actions. How did he use his agency to influence the behavior of the system and, more broadly, what does that tell us about leadership in complex systems? How can leaders encourage the outcomes they desire? Those were some of the questions I was looking to explore.

I believe this perspective is helpful for today because it enhances our understanding of leadership and what makes it effective. Complex systems theory helps us recognize the non-linear nature of so much of what we experience. There was an excellent article in the Naval War College Review that discussed this in the context of human conflict—“War is the Storm” by B.A. Friedman—and there is increasing recognition of the value of that perspective. However, most examinations of leadership still embed an assumption of linear causality. They assume that a sufficiently inspired leader can just take the right action and the desired outcome will follow. This is fundamentally misleading and I believe it holds us back. It is not that straightforward or that easy.

I wanted to provide what I think is a more accurate perspective, one that recognizes that leadership is not linear. It is not a simple problem with globally applicable patterns. It requires a deft touch, contextual sensitivity, and an ability to foster connections and relationships that may indirectly lead to desired outcomes. A leader cannot just do X; they have to inspire action toward the desired outcome (Y). Nimitz knew this and I tried to illustrate how his leadership can be better understood through the lens of complex adaptive systems.

In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, you credit Nimitz’s aggressiveness in having Halsey conduct the early carrier raids into the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, as well as the Doolittle Raid. You describe the raid as having limited tactical impact but significant strategic impact, partly because it slowed Japanese advances against New Guinea and Ceylon, for fear of further American attacks. While historical research offers answers with the benefit of hindsight, by what process can leaders determine their present opportunities which may appear insignificant, but may in fact greatly affect adversary decision-making?

It might be valuable to start with specifics. In those early months of World War II, signals intelligence and codebreaking provided Nimitz with the information necessary to understand that he was impacting Japanese decision-making. However, the point of your question—and the value of it—is to generalize and I think the general point is that Nimitz was open to new information from a variety of sources. He was trying to create what we might call a “sensor network” that would allow him to gather information that he could use to further Allied strategy. Signals intelligence emerged as an effective means to do that, and so retrospectively, we can look to that as the key. However, at the time Nimitz did not have the luxury of focusing exclusively on one source, so he used multiple ones. Submarine reconnaissance is one that doesn’t receive a great deal of credit, but it was very important to those early raids, especially in the central Pacific.

If I were to generalize further, I think an important lesson is that information gathering mechanisms both highlight and filter. They draw attention to the things they expect and dismiss things they don’t, creating a kind of hidden blindness. Nimitz was fortunate in early 1942 that the Navy’s established mechanisms for information gathering were relatively informal. Structures weren’t overly rigid. That meant he could access a variety of sources and shape his relationship with those sources. The fractured nature of the Navy’s intelligence organization—which often failed to reach consensus—at that time might actually have been beneficial in this respect.

Today’s leaders need to be thinking about potential sources of blindness inherent in their organizations and how they might gather alternative perspectives to overcome them. Organizational structures enable, but they also constrain. Nimitz seemed to have an intuitive understanding of this.

By far my favorite historical anecdote in your book is from early in the war. Nimitz and his recovering Pacific staff are “maintain[ing] a clear sense of the unfolding engagement [in the Battle of Midway] at Pearl Harbor, using a large plot ‘laid over plywood across a pair of sawhorses.'” It is amusing to imagine now given our focus on high-end computing and battle management systems at Maritime Operations Centers or on ships today. As you were doing your research, did you have a favorite anecdote or example of how Nimitz, his team, or his subordinates were getting it done given what they had?

I love the idea of an analog plot on a physical map over sawhorses. I was disappointed when the most recent Midway movie showed a much more sophisticated plot at CINCPAC headquarters. If the film been more accurate, I think it would have made Woody Harrelson’s portrayal of Nimitz more accessible (and more accurate). And while we’re on the subject, I do think there’s a value to physical plots that digital interfaces don’t provide. I’ve seen it in my work; the physical act of moving things on a shared visualization prompts learning and thinking in a way that digital artifacts do not.

My favorite anecdote about Nimitz and his staff “getting it done” happened in late September 1942 during Nimitz’s flight from Espiritu Santo to Guadalcanal aboard a borrowed B-17. When they arrived over Guadalcanal, the weather was poor and the USAAF pilot could not find Henderson Field. Fortunately, Cdr. Ralph Ofstie, who was an aviator on Nimitz’s staff, remembered that Lt. Arthur H. Lamar, Nimitz’s aide, had brought a National Geographic map of the South Pacific. Ofstie borrowed it and used it to navigate the B-17 to a safe landing. I think that was a remarkable “get it done” moment and it is worth imagining what might have happened if Ofstie hadn’t been able to find the field. Unfortunately, I did not include that story in my book. As much as I like it, I sacrificed it for broader themes about organizational structure and planning. I had a word count to contend with and cut a lot of things that were potentially really interesting, but not aligned with my broader themes.

In the past few years in the U.S. Navy, we have seen some fairly high-profile dismissals for cause due to a lack of trust and confidence of leaders in their roles. You do a great job documenting how even coming into the job, Nimitz had to win and maintain the trust and confidence of his superiors (President Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, and Admiral Ernest King) and restore the faith of his new subordinates (namely, the Pacific Fleet staff). Besides the basics of battlefield success, what do you think Nimitz did that improved trust and confidence up and down his chain of command, that Navy leaders at all levels can employ today?

I was very impressed with Nimitz’s ability to use one-on-one conversations and personal relationships to promote shared understanding and address difficult topics. Three specific occasions come to mind.

In early February 1942, Nimitz sent Vice Admiral William S. Pye to Washington to meet with Admiral Ernest J. King, the Navy’s new commander in chief. Pye had been the interim commander of the Pacific Fleet after Admiral Husband Kimmel was relieved in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, and Nimitz kept Pye on as an advisor. February 1942 was a crucial time. The Japanese were advancing rapidly through the Netherlands East Indies and King was pressuring Nimitz to take some aggressive action that would disrupt the Japanese offensive. Nimitz knew he didn’t have the capability to raid in the central Pacific in strength (King urged him to use battleships, for example), but King was very insistent and, in modern terms, was micromanaging the situation.

I am not sure what Nimitz said to Pye before he flew to Washington. I am also not sure what Pye said to King when they met. However, King’s attitude changed after his meeting with Pye. Some of that may have been because of the February 1 raid on Japanese positions in the Marshalls and Gilberts, but I think Pye’s conversation with King was more important for King’s attitude shift. King and Pye had known each other for a long time and worked together before. Nimitz knew that if anyone could clarify the situation at CINCPAC HQ for King, it was Pye. It was a very deliberate choice on Nimitz’s part and the record suggests it had important outcomes.

The second occasion was the first wartime meeting of King and Nimitz in April 1942. Prior to the meeting, King’s impression of Nimitz was not entirely favorable. King thought Nimitz was a personnel specialist who lacked the decisiveness to lead the Pacific Fleet in wartime. This was perhaps not an unreasonable assumption because of the time Nimitz had spent serving in and leading the Bureau of Navigation (which would later become the Bureau of Personnel).

Nimitz showed up to that meeting armed with a plan to ambush a substantial portion of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s First Air Fleet—the aircraft carriers of the Kidō Butai—in the Coral Sea. Codebreaking had given Nimitz insight into Japanese plans to seize Port Moresby by sea, and Nimitz intended to trigger a major battle with all four of his available fleet carriers. King didn’t approve the operation right away, but he eventually did before Nimitz returned to Pearl Harbor. Nimitz’s plan ultimately didn’t work out; two of his carriers failed to arrive in time for what became the Battle of the Coral Sea. However, the two carriers that were there won a strategic victory and, after that first meeting, King was much more willing to trust Nimitz to fight.

The third occasion was immediately before the Battle of Midway. Nimitz had planned to give Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr. command of his carrier forces, but Halsey was ill. Nimitz put Rear Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, who had commanded the carriers at Coral Sea, in charge of the carriers. Now, Nimitz and King were not entirely satisfied with Fletcher’s performance at Coral Sea. King, for example, felt Fletcher should have initiated a night search and attack with his destroyers. So, Nimitz pulled Fletcher aside and had what I imagine must have been a delicate conversation. Nimitz let Fletcher know where his performance appeared to have fallen short. At the same time, Nimitz offered encouragement and expressed his faith in Fletcher’s ability to command the coming battle. Anyone who’s had to have a conversation like that with a subordinate, where you offer critical feedback while also inspiring them to better things, knows it is tricky. Nimitz was good at it.

In each of these instances Nimitz used his interpersonal skills to directly address sources of potential conflict and misunderstanding in one-on-one conversations. He “leaned in” to that kind of friction and used it as a way to increase clarity about what he expected and what he intended to do. This approach increased trust and confidence. I think that commitment to surface potential conflict and address it before it becomes a more serious issue is an excellent lesson to take forward.

Throughout the book, you credit Nimitz for staff adjustments and flexibility to maintain a sensing organization, from fielding the first Joint Intel Operations Center, or making adaptations on ships like directing crews to set up a Combat Information Center. I was especially impressed with how Nimitz provides an end goal without specifics, which creates something like a meritocratic laboratory at sea for lessons learned to bubble up. If you were to distill Nimitz’s sensemaking-to-organization-adjusting process, how can staff or fleet leaders use that today for some of our emerging challenges that include far more services and capabilities than what Nimitz had to organize? As a leader, how do I discern that my organization is not sensing problems effectively anymore and requires change?

There are several aspects to this. First, it is important to have a high-level goal that focuses effort on a desired outcome. Innovation and creativity must be fostered and often the best way to do that is to work across or through existing organizational boundaries. A high-level goal helps with this because if the goal is small or too easily achievable it can easily be broken down and approached within an existing organizational structure. That constrains the solution space and limits potential solutions. Conway’s law, which holds that a solution design mirrors the communication structures of the organization that created it, is an excellent example of this idea.

The Combat Information Center (CIC), and the innovative work that led to it, benefited from cross functional collaboration in pursuit of a high-level goal. The CIC required adjustments to the Navy’s existing shipboard organizational structure. If the problem had been broken down into smaller pieces and solved within that structure, it would not have led to the transformational solution that became the CIC.

Now to the question about how one knows if their organization isn’t sensing problems effectively anymore. I think the best answer to that is not to look for some kind of trigger to see if effective sensing has stopped. Instead, I think it is best to assume that sensing is always slightly off and never fully accurate. Therefore, organizations need an inbuilt capacity to continuously adapt, adjust, and reassess. Otherwise, that capability will not be there when it is really needed. In the book I build off the work of David Woods and use his perspective on adaptive capacity and his theory of “graceful extensibility.” Both rely on having sufficient spare cycles (spare capacity) to reflect on the current state and adjust to new information. I believe that is something that Nimitz and other officers like him actively sought to create, an ability to adapt, adjust, and reconfigure on a regular basis to keep pace with the evolving nature of the war. It is a point I make in the book.

All of this necessitates a comfort with flexibility, in terms of organizational structure, and uncertainty, in terms of one’s role and the part one will play to achieve desired outcomes. I think that comfort with uncertainty and variability is very important. It is something that can be nurtured, and so if there’s one thing that today’s readers take away, I think it ought to be that. How do they foster the necessary comfort with uncertainty so that they and their teams can be ready to adapt to the new and unanticipated? In a Proceedings article I co-authored with Lieutenant Eric Vorm, he and I called this “intellectual readiness.” I think it is a good model for how to think about it.

One lesser-known story for me was the American efforts to dislodge or deny Japanese attacks on the Aleutian Islands in the North Pacific. It seemed like personality clashes on the ground and staff planning affected joint operations nearly as much as the weather did. What differences do you see in the more flexible Southwest and Central Pacific advances that weren’t present in the Northern Pacific, and what do you think Nimitz might offer as advice for working with conflicting personalities and visions for a mission?

I’m glad you found the discussion of the Aleutians valuable. I think it is an important aspect of the war that is sometimes overlooked. The crucial difference between the Aleutians and the South Pacific and Central Pacific was lack of unity of command. Nimitz expected Rear Admiral Robert Theobald to establish a unified command structure—at least a sufficiently well-aligned understanding with his U.S. Army counterparts if not a shared organizational hierarchy—but Theobald did not do that. In this sense, personalities matter, and those personalities need to be able to subordinate their service loyalties and personal pride to the pursuit of strategic objectives. Nimitz’s subordinate area commanders who were able to do this—Admiral Halsey, who collaborated with General MacArthur in the South Pacific, and Admiral Kinkaid, who worked well with the Army in the North Pacific and then with MacArthur in the Southwest Pacific—succeeded. Those who did not were relieved.

Geography played an important role too, of course. There were more options for maneuver in the Southwest Pacific and Central Pacific, more pathways to strategic objectives. The North Pacific was necessarily more linear because of the arrangement of the Aleutians. Even still, Kinkaid was able to leapfrog Kiska and seize Attu. That was a very creative solution to the resource constraints he and his peers in the Army faced and it ultimately made the Japanese position on Kiska untenable, easing its recapture.

I think Nimitz’s advice would be to collaborate and think creatively across service and national lines. He encouraged this regularly. One specific instance stands out. When he visited the South Pacific in September 1942, before Admiral Halsey relieved Admiral Ghormley, he told the attendees of one conference, “If we can’t use our Allies, we’re god damn fools.”

You recount how in the final planning for the mainland invasion of Japan, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) realized they can’t choose Nimitz or MacArthur as overall theater commander, as neither was willing to be subordinate to the other, with the General designated Chief, U.S. Army Forces, Pacific (CINCAFPAC), and the Admiral responsible for “all U.S. Naval resources in the Pacific Theater” except for those in the Southeast Pacific. The first de facto Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Bill Leahy, “felt the implications were ‘somewhat academic,’” but you say there were significant consequences, because it “discarded Nimitz’s integrated approach to joint command…. in favor of MacArthur’s centralized approach… in effect [making] the JCS the [General Headquarters] GHQ for the Pacific theater.” Can you expand on those consequences, and as a civilian academic observer, how do those lessons inform your view of our current Geographic Combatant Command structure, which looks very much like the end-of-war model, albeit with a single individual in theater and in command, rather than the JCS?

I didn’t fully appreciate those late war organizational adjustments until I got into them and analyzed their implications. A little background is important. Both Nimitz and MacArthur employed “unity of command” in that all the forces in their respective theaters were under their command (the one important exception being the USAAF’s strategic air force in the Marianas). However, Nimitz and MacArthur approached that idea differently below their headquarters level.

Nimitz maintained unity of command even at lower levels of his command structure. Halsey, for example, commanded all the forces in the South Pacific Area, and Spruance, when he commanded the Fifth Fleet, controlled not just the ships of that fleet, but also its amphibious forces and supporting land-based planes. That meant that when Spruance wanted to use Army B-24s in the forward area to scout for his carrier forces, he could just order them to do so. He didn’t need to request permission from a parallel command. Nimitz’s approach was especially important for major amphibious operations. Command rested with a single commander who could coordinate all the forces involved. Usually, for an amphibious operation, that was a naval officer.

MacArthur approached the challenge differently, and maintained a separation of the services—Army, Navy, Army Air Forces—below the level of his headquarters. So, both MacArthur and Nimitz used unified command, but because they unified at different levels, the implications were different. Coordination in MacArthur’s theater required more cross-service collaboration, and, unsurprisingly, he had a larger headquarters as a result. More officers were needed to deal with the greater administrative burden. That coordination also cost time. Late in the war, once the services started to unify across the Pacific, Halsey wanted land-based air support. Instead of just ordering it like Spruance had, Halsey had to wait for his request to go up the command chain to Nimitz, over to MacArthur, and back down to the USAAF planes he needed. That cost time and effort.

The ramifications of this have largely been ignored because by the time the changes took place the war was almost over. The last major operation, the capture of Okinawa, was already under way and although the invasion of Japan was in the planning stages, it did not take place. However, had it taken place, the implications of the new approach would have been very evident. In effect, unity of command in the Pacific had been abandoned. MacArthur was given the Army (and Army Air Forces, again with the exception of the strategic air force) and Nimitz the Navy. They would have had to coordinate and collaborate to successfully invade Japan, and the only place their command chains met was at the JCS. We can see the challenge this presented even in the planning stages. When preparing for the invasion, MacArthur was quite willing to escalate his disagreements with Nimitz to the JCS and pull them into operational planning decisions, such as command arrangements for the amphibious assault on Kyushu.

I appreciate you linking the combatant commands to the late-war Pacific organization; I hadn’t considered that. As someone who studies naval history, I think the Geographic Combatant Command structure is problematic, but for a different reason. Naval strategy ought to be global in scope. Unfortunately, the combatant command structure assumes that U.S. strategic interests can be geographically compartmentalized. I don’t think that’s true, and I think the emphasis on combatant commands has hindered—or, perhaps more accurately, disincentivized—the development of a global strategy that maximizes the nation’s ability to achieve its geopolitical goals. Instead, the emphasis on optimizing each individual command has led to suboptimizing the whole, which, if you think about it, is a logical outcome from a systems theory perspective. It is like the high-level goal idea from your earlier question about sensing organizations. The current structure constrains the solution space and confines it to things combatant commands can solve. The challenges the U.S. faces are bigger than that.

Is there anything we haven’t talked about from your book that you feel is important and would like to share?

I alluded to risk earlier, but I think it’s important to stress Nimitz’s approach to it and how it differs from today’s accepted wisdom. Nimitz is famous for emphasizing “calculated risk” at Midway, and appropriately so, but most analyses I’ve seen emphasize the “calculation” and not the “risk.” That makes sense from a contemporary perspective; we tend to assume risk is something we can design out.

Nimitz felt it was something that had to be embraced, that great victories were not possible without embracing a corresponding degree of risk. I think that’s a more appropriate way to view Midway. Nimitz was definitely calculating, but the great risk was not the positioning of the carrier forces. Instead, it was the decision to fight for Midway, to make it the focal point of the ambush Nimitz had been seeking since late April.

Because Nimitz’s gamble worked out, it’s hardly ever questioned, but it was a significant risk. If the Japanese had focused elsewhere, if Midway had been a feint, our view of Nimitz might be very different. He was willing to take that risk because he thought the upside was worth it. He was willing to gamble.

For some final takeaways, what are you reading, what’s next for you, and where can people interact with you or your work in the future?

I’ve got a reading stack that grows faster than I can consume it. One really interesting book I read lately was The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow, which presents an alternative view of human societal evolution. It is powerful because it undermines the narrative that society evolved in a linear, predictable way and suggests that there are many more alternative approaches to organization and government than we tend to assume.

I also really enjoyed Mike Hunzeker’s Dying to Learn. It is a great complement to my own Learning War. I believe Dr. Hunzeker did an interview with CIMSEC about it. He and I were on a panel together at the Society for Military History’s annual conference, so I wanted to get up to speed on his perspective.

I am also working on a number of things. I recently published an article on the evolution of World War II Pacific logistics in the Journal of Military History. I have co-edited a newly released volume on naval night combat called Fighting in the Dark that covers the period from the Russo-Japanese War through World War II. The U.S. Navy’s approach to night combat has always been of great interest to me, and for that book, I wrote a chapter on the U.S. Navy which focuses on the increasing use of the CIC in 1943 and 1944. I have also got a chapter planned for a Naval War College project, and another book in the works with the Naval Institute Press, on another famous admiral.

Trent Hone is an authority on the U.S. Navy of the early twentieth century and a leader in the application of complexity science to organizational design. He studied religion and archaeology at Carleton College in Northfield, MN and works as a consultant helping a variety of organizations improve their processes and techniques. Mr. Hone regularly writes and speaks about leadership, sensemaking, organizational learning, and complexity. His talents are uniquely suited to integrate the history of the Navy with modern management theories, generating new insights relevant to both disciplines. He tweets at @Honer_CUT and blogs at trenthone.com.

Lieutenant Kyle Cregge is a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer. He is the Prospective Operations Officer for USS PINCKNEY (DDG 91). The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or the Department of Defense.

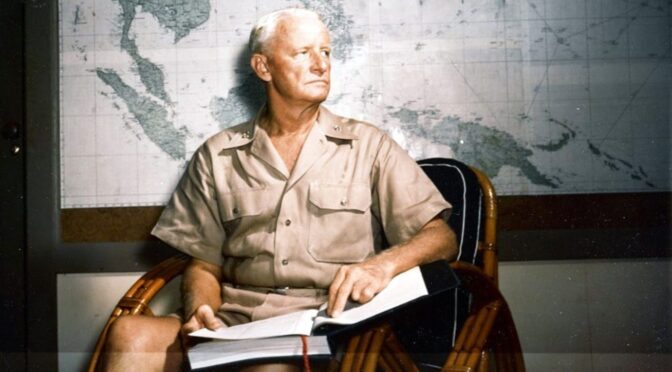

Featured Image: Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, in his office at CinCPac / CinCPOA Advanced Headquarters at Guam, in July 1945. (NHHC photo)