By Captain Benigno R. Alcántara Gil, Dominican Republic Navy

Introduction

The popular “Thucydides trap” implies that fear of a growing hegemonic power is a fundamental reason for a nation to go to war with another.1 Under this premise, many have argued that Britain, as an insular power, feared the German naval build-up of the early 1900s as the most severe threat to Britain’s mainland security and, as such, it was the primary cause of Anglo-German conflict in World War I.

Nonetheless, the fundamental cause of the conflict was aggressive German foreign policy carried out in complete disregard for geopolitics, by means of irrational diplomacy as well as a series of hostilities that undermined regional dynamics and the European balance of power. Three reasons support this claim.

First, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s foreign policy, known as Weltpolitik (world policy), communicated aspirations for world domination and thus instilled grave uncertainty about the preservation of peace and the European balance of power.

Second, back then, other rising powers were also building up and modernizing their naval services (such as the United States, France, Russia, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Japan). The German naval build-up only served to accentuate antagonism and mightier naval accrual for the British fleet, which remained proportionally superior in tonnage and readiness.

Third, the violation of Belgium’s neutrality confirmed Germany’s full political determination to alter Europe’s equilibrium through war. The assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, plus the emergence of questionable alliances, constituted a threat to peace, economic performance, and freedom of commerce.

Erratic Diplomacy and the Balance of Powers

Kissinger described the European diplomatic continental theater in the period before the Great War (World War I) as a “political doomsday machine,” his reasons were based on many diplomatic flaws and series of questionable German endeavors that lead into an escalation toward war.

Before discussing the erratic shifts in German diplomacy under Kaiser Wilhelm II, it may be helpful to establish common ground about two concepts copiously used hereafter: diplomacy and balance of power. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines diplomacy as the “art and practice of conducting negotiations between nations.”2 Encyclopedia Britannica provides a broader description: “The established method of influencing the decisions and behavior of foreign governments and peoples through dialogue, negotiation, and other measures short of war or violence.”3 Kissinger put it in much simpler terms as “the art of compromise,”4 and “the adjustment of differences through negotiation,”5 referring to an ability to create cooperation, settlement, agreement, or commitment.

Likewise, the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines balance of power as “equilibrium of power sufficient to discourage or prevent one nation or a party from imposing its will on or interfering with the interests of another.”6 Moreover, theoretical consensus holds that such balance in the continental system works best if at least one of the following conditions is present:

- A nation should be free to align itself with another nation in the same way;7 continually shifting alignments could also maintain equilibrium, as evidenced by Otto Von Bismarck’s diplomacy in his application of Realpolitik.

- Whenever there are free alliances, there is a balancer that could ensure that none of the existing alliances becomes the only predominant force. This was Great Britain’s role just before it joined the Triple Entente.8

- There can be rigid alliances and no balancer, as long as the level of cohesion is flexible enough to allow for changes in alignment upon any given event.9 The rationale for power equilibrium holds that if none of the previous conditions prevails in a system, diplomacy turns “” This leads into a zero-sum relationship among participating nations, and where this condition leads to armament races such as naval build-ups, and consequently to escalated tension such as those experienced during the Cold War.10

Returning to Kaiser Wilhelm II and Weltpolitik, it may be useful to provide a brief description of the Kaiser’s competencies as a national leader, from a critical perspective. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, during his war declaration against Germany in a speech to Congress, deplored Wilhelm II’s unprovoked assaults on the international order. He depicted the Kaiser as an individual with complete disregard for universal rights, and as the person responsible for propelling an immoral war in the self-interest of the dynasties.11

Conversely, Kissinger labeled the Kaiser’s diplomacy as both irrational and unsound, for he drove the German empire on a quest for a new world order without a clear understanding of historical relationships and underlying diplomatic dynamics. The Kaiser proved himself indifferent to possible contingencies and inflexible toward alternate courses of diplomacy.

Dismissing Otto Von Bismarck from office, and not capitalizing on the vast knowledge of such an illustrious chancellor, was another remarkable mistake (some historians suggest that Wilhelm II dismissed Bismarck out of personal insecurity, rather than because of criteria or substance).12 A rational political leader would have considered keeping a man of such stature and experience handy, either as an advisor or as a counterbalance. Conducting foreign policy with a heavy-handed and bullying assertiveness, threatening the other European powers with insecurity, and increasing uncertainty was a rapid way to undo the alliance system carefully achieved through Bismark’s Realpolitik.

In terms of the alliance system, it is essential to point out that Bismarck favored validating Prussia as a great power, rather than creating a grand nation-state that included Austria-Hungary. The Kaiser favored the latter option, falling short in his appreciation of the geopolitics of Europe. Furthermore, Kaiser Wilhelm II rejected an offer from Tzar Nicholas II to extend for another three-year term the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia; this breakage caused Germany to lose leverage with Austria-Hungary. Bismarck had used it to maintain a balancer position, keeping Vienna in check and Russia as a relative friend.

By breaking the treaty, Germany sent unclear signals to an already anxious Moscow, which paved the way for France to seek understanding with Russia, which suspected that the breakage was due to German support to a potential Austrian incursion in the Balkans. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s rejection of Russia’s agreement occurred because he did not want to inherit complex alliance entanglements. Also, the Kaiser wanted to reassure Austria of Germany’s support and because he saw Russia’s agreement as an obstacle to allying with Britain (which he preferred over Russia). Consequently, the Franco-Russian agreement took place in 1894, in which France would aid Russia in diplomatic issues with Great Britain, likewise, both powers would support each other in the case of German aggression (whether by itself or with its allies).13

Another costly diplomatic misconception took place when the German and the British governments signed a colonial agreement where they exchanged and settled African colonial issues. The colonial agreement was very beneficial for both parties; however, it brought a series of misunderstandings, mainly because Germany envisioned the agreement as a new stage in bilateral relations and as a prelude to an Anglo-German Alliance.14 Thus, German diplomats ignored important historical precepts set by the British “Splendid Isolation” policy15 and instead continued to push for a formal alliance assertively. However, Britain rejected a formal entente, which hurt Kaiser Wilhelm II’s feelings and pride, thus missing the geopolitical and strategic perspective, and failing to realize that to be safe with Britain, a simpler accord of neutrality would have sufficed. Despite the British disposition to enter in a less formal cooperation entente with Germany, the Kaiser rejected such informality and again demanded a formal alliance with legal binding. Consequently, Britain rejected any type of accord with Germany.16

Kissinger affirmed that an informal accord to keep Britain as a benevolent neutral in case of a continental war was far more valuable than any other type of legal agreement, for Germany could have won any conflict as long as Great Britain remained unaligned. However, German impatience and intransigence sent the opposite signals to Great Britain and generated substantial doubts about Germany’s true intentions.17

After nearly 15 years of inconsistency and disquieting foreign policy that bullied the European balance of power, Germany managed to isolate itself. It went from having a genius system of alliances that allowed it to preserve its relative equilibrium, to virtually isolating itself on the continent. Simultaneously, it took about the same time to extinguish each of the conditions that ensured the balance of powers in the European theater. This imbalance ignited the armament race, which later turned into tests of strength, which after the violation of Belgium’s neutrality, ultimately triggered Britain’s declaration of war against Germany.

Germany‘s Naval Build-up

The German and British arms race emerged from the deterioration of the European balance of power. Nevertheless, despite the undeniable budgetary constraints and heightened public anxiety the German build-up instilled upon the British admiralty, Britain remained the naval hegemon with unmatched naval superiority and unrivaled naval warfare prowess.

In fact, despite the build-up, the German fleet still could not compete navy-to-navy with the British fleet, neither in size nor in naval warfare competencies. According to figures and statistics presented by Paul Kennedy, the naval build-up was not sufficient to jeopardize Britain’s indisputable control of the sea. For instance, at the height of the arms race, Germany’s total warship tonnage was estimated around 1.3 million tons, while Britain’s total warship tonnage was around 2.7 million tons.18

Conversely, if the issue had been the naval build-up, then the U.S. naval build-up would also be equally threatening to Britain. The U.S. became a mighty maritime power in the western hemisphere, where its build-up gave it the next largest fleet after Germany’s, with a total warship tonnage of about 900,000 tons. Incidentally, the United States also contested European powers at sea through the application of the Monroe Doctrine in the western hemisphere. Moreover, it directly contested Britain’s maritime hegemony and achieved political concessions over the Venezuela disputes, Isthmian Canal, and the Alaska boundary. One could wonder why this did not translate into an Anglo-American conflict.

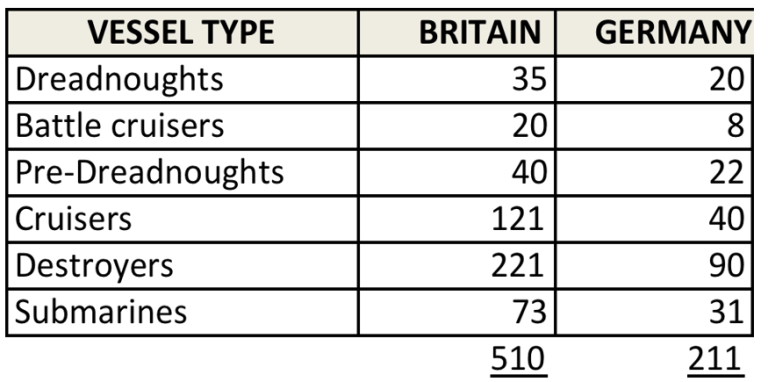

Because of the grave anxiety produced by Weltpolitik throughout Europe, the antagonist naval arms race only served to encouraged a mightier naval accrual for the British side as part of a natural reactionary response to competition. David Stevenson also depicted the total number of warships on each side, revealing the extent to which the Royal Navy outnumbered the German Navy.19

According to Stevenson, the German build-up conceived by Wilhelm II, Admiral Alfred Von Tirpitz, and Bernard Von Bulow never envisioned to actually fight Britain, but rather to use the fleet as a negotiation advantage to encourage Britain to come to terms and make concessions in a future crisis.20 Conversely, Germany formally negotiated not to employ its navy against France and to slow its naval build-up in return for British neutrality in the conflict. Britain turned down both offers in 1909, which implies that the build-up was not Britain’s main concern.21

Why was the Build-up so Frightening?

Some blame the extraordinary German industrial boom, as it supported the rapid and massive military build-up, as well as the robust economic growth experienced in the years preceding the war.

German figures (1910-1914) depict notable increases in all areas of national development. For instance, German military personnel approximately rose by 30% (67% over Britain), relative shares of manufacturing output grew by 15% (14% above Britain), total industrial potential increased by 80% (8% over Britain), iron and steel production increased by 30% (128% over Britain) and more importantly, warship tonnage increased by 35% (about 50% less than Britain).22

The speed and magnitude of the German naval armament build-up seemed to threaten the British hegemonic position in control of the sea. Sir Eyrie A. Crowe;23 in his famous memo, dated January 1, 1907), explained why an accord with Germany was not feasible and why German capabilities were more important, per his views. In his own words: “Germany was aiming at a general political hegemony and maritime ascendancy, threatening the independence of her neighbors and incompatible with the survival of the British Empire.”24

Britain’s insular and advantageous geopolitical position could also have become a source of concern, as the tranquility of Britain’s maritime buffer could only be threatened by hegemonic continental German rule, assisted by an overwhelming naval build-up. Moreover, the influence of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan’s theoretical constructs about “sea power”25 only reinforced the strategic value of sea power and sea control on both sides. Furthermore, both British and the Germans, as avid readers of Mahan, understood the concept “command of the sea,” and Kaiser Wilhelm II did try to rely on this knowledge to secure an accord with Britain. However, the British realized that such an alliance would only constitute a temporary placebo. The fear of unexpected dramatic shifts if Britain had remained neutral or if it had entered alliance would have allowed Germany to become a continental hegemon that would later contest Britain’s command of the sea.

Consequently, the British instead embraced the French entente which was more friendly to the British maritime hegemon, and where the 1912 Anglo-French Naval Convention did not endanger Britain sea power. Therefore, the French carefully crafted the entente with Mahan in mind.

Pre-Conflict Kinetic Dynamics

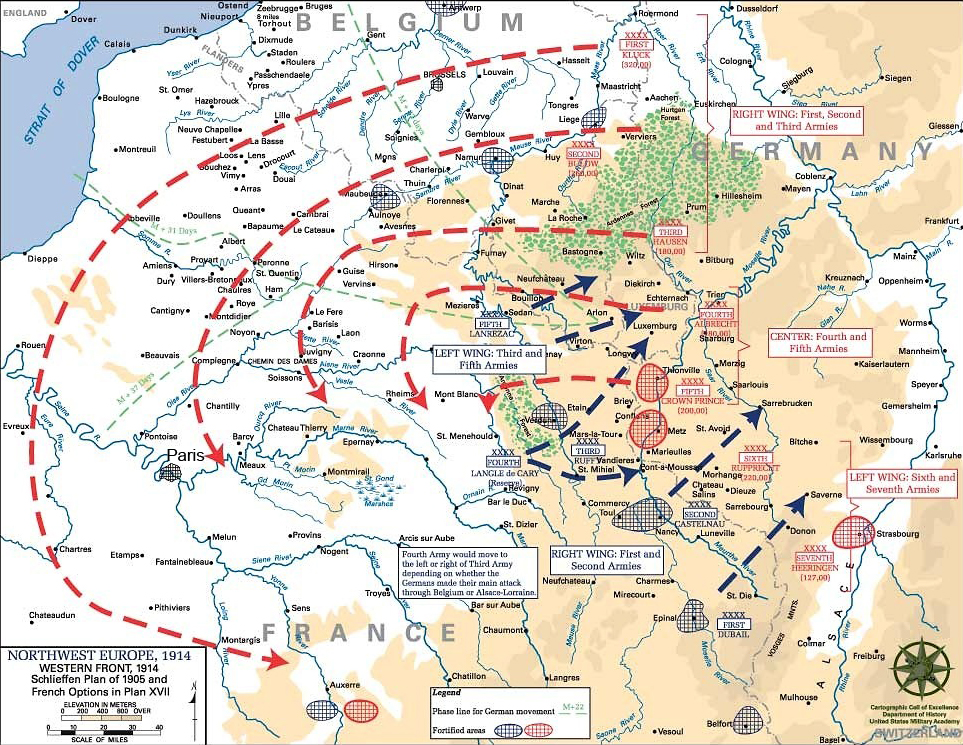

Germany’s mobilizations in support of Austria-Hungary and the violation of Belgium’s neutrality confirmed a clear disruption in Europe’s balance of powers, and ultimately served as casus belli.26The German mobilization was an important part of the Schlieffen Plan,27 where the plan pre-calculated a scenario based on time, force, and space considerations. Significantly, it included violating neutral countries in order to attack France. For this reason, the German Army presented the monarchy of Belgium an ultimatum for free passage through Belgium, which the Belgians refused under the claim of neutral status in the war. As a consequence, German troops invaded neutral Belgium on August 4, 1914.28 In essence, the Schlieffen Plan aimed to destroy the French Army by a direct and swift attack on its own soil, and where this preemptive attack expected to capture Paris and trap the French Army in just six weeks. Then Germany would turn toward Russia before it could complete the full mobilization of its army.29

Despite German acknowledgement of the Treaty of London with the Low Countries (the kingdoms of the Netherlands and Belgium), the German plan contemplated a violation of Belgium and the Netherlands.30 However, it did not account for potential British involvement, despite the fact that Britain was determined to protect the Low Countries from any major power incursion.31

Notwithstanding, on June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a militant in a Serbo-Croatian revolutionary group called “Young Bosnia” (a group affiliated with the Serbian paramilitary called “Black Hand”) assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand along with his wife in Sarajevo.32 The Archduke’s assassination led to Austria-Hungary (which was backed by Germany) to declare war on Serbia. Unreceptive of Serbia’s official reparation offers and willingness to work out a peaceful solution, Austria-Hungary mobilized against Serbia. In the background, Russia and France entered an entente to back Serbia. In parallel, Germany made pacts with the Ottoman Empire, and it later attacked France. Britain made up her mind and resolved to join the triple entente with France and Russia. In the distance, the United States remained vigilant but did not join the war theater until later.33 Although put in a rather simplistic narrative, it illustrates the convoluted political and kinetic dynamics that resulted in gross miscalculations that completely fractured Europe’s balance of power and thus led to the Great War.

Conclusion

Arms races and military build-ups are a recurring phenomenon in global politics even today. Today’s media features multiple headlines such as “Military build-up in the vicinity of the recently annexed Crimea”;34 “China’s menacing naval build-up and claims about its territorial seas, the Spratly and Paracel islands”;35 and news about Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) tests from North Korea, as well as massive armament build-ups despite the peace pact with South Korea.36

The second headline in particular relates directly to the essence of what has been discussed herein and applies to an ongoing naval build-up between two indisputable superpowers, the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Reportedly, the U.S. Navy augmented its ship production goals to attain a 355-ship fleet (up from around 290 ships today). More recent force structure assessments put the desired number even higher, at more than 500 ships. Recognizing the need for more Arleigh Burke-class Aegis destroyers (DDG-51) to counter growing ballistic missile and anti-ship missile threats,37 the U.S. is bringing its DDG-51 production to a total of 85.38 In contrast, the Chinese Navy (PLA Navy) has surpassed the U.S. Navy in overall numbers of battle force ships.

According to a U.S. Congressional Research Service report, the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) estimated that by the end of 2020 the PLA Navy would attain 360 battle force ships, compared with a projected total fleet of 297 ships for the U.S. Navy at the end of the year. ONI also projects that the PLA Navy will have 400 battle force ships by 2025, and 425 by the end of 2030.39

Besides the naval issues, ongoing commercial and trade disputes between China and the United States have substantially affected international markets. The effects of the so-called “trade war” reflects in the balance of payments, economic performance, and economic growth of many countries around the globe. The world economy not only had to revise (lower) its growth potential expectations but also had to accept prospects of an equally adverse and pessimistic trade outlook for the near future.

Nevertheless, it is always worrisome when reactionary political countermeasures and economic retaliation takes the place of sound high diplomacy from a global perspective. For instance, the current bilateral arms race among major powers today includes and is not limited to the production of aircraft carriers, surface combatant ships, combat aircraft, submarines, unmanned vehicles, anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), anti-ship cruise missiles, and C4ISR (command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems.40 As such, logic dictates that no superpower would benefit from this competition, for in an age with so many nuclear-capable nations, a clash that could escalate to thermonuclear levels will only yield losses and disaster on a global scale. It would be like if no lessons were learned from the Cold War period (1947-1991), a period that kept the world under the stress of continuous geopolitical tension and uncertainty due to the cataclysmic implications of nuclear-capable great powers.

Clausewitz41 wrote about the complexity of war; how nations are typically driven into conflict due to a combination of factors, such as, military capability, the political value of the object (aims), the geopolitical governing dynamics, and social sentiments and passions (people and public opinion). The Anglo-German conflict occurred due to a series of cascading and unfortunate events in Europe, including the July Crisis, along with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Serbia’s attack, and the violation of Belgium’s position of neutrality.

Today, the world’s balance of powers will depend upon sound diplomacy under the terms of legitimacy, specifically under the terms of Clemens Von Metternich.42 Conversely, sound diplomacy shall refer to a consensus within the framework of the international order of all major powers, put in Kissinger terms, to the extent that no state is so dissatisfied (as Germany was after Versailles) that it will engage in deliberate violation of international treaties, of the international rule of law, and another state’s national sovereignty.43

Captain Alcántara was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. He is a graduate from the Dominican Naval Academy with a Bachelor in Naval Sciences (1996). He holds masters degrees from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School (MBA, 2005), and from Salve Regina University (MSc, 2017). He is also a proud alumni of he U.S. Naval War College, Naval Command College (Class of 2017), and the Naval Senior Leadership Development Concentration track (NSLDC), U.S. NWC.

Bibliography

1. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster. (1994).

2. Stevenson, David. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. New York: Basic Books, (2004).

3. Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Random House. (1987).

4. Kissinger, Henry. A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the problem of peace, 1822-22. Friedland Books. (2017).

5. Mahan, Sir Alfred Thayer. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History: 1660–1783. Little Brown and Company. Boston. (1890).

6. (423 BC). Robert B. Strasser. The Landmark: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. Touchstone, New York. (1996).

7. Keegan, John. The First World War. (2000).

8. Kossmann, E. H. (1978). The Low Countries, 1780–1940. Oxford University Press. (1st edition).

9. O’Rourke. China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities. (2020).

10. H.I. Sutton. Aerospace & Defense. Forbes. (2019).

11. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary online.

12. The Encyclopedia Britannica online.

13. Business Insider online.

14. The Wall Street Journal online.

15. The New York Times online.

16. Foreign Policy Magazine online.

Endnotes

1. Thucydides (423 B.C.) edited by Robert B. Strasser. The Landmark: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. Touchstone, New York. (1996). Ancient war correspondent and historian, Thucydides wrote, “The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta, made war inevitable.” Further, history seem to have validated this theory, for almost on every occasion a rising power threatened to displace (Instilled fear) a ruling one, the result has usually been war.

2. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/diplomacy, accessed on 03/31/2017.

3. Chas. W. Freeman & Sally Marks. Meaning of diplomacy. https://www.britannica.com/topic/diplomacy, accessed on 03/27/2020.

4. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 182.

5. Kissinger, Henry. A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the problem of Peace, 1822-22. Friedland Books.2017.

6. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/balanceofpower, Accessed on 03/31/2017.

7. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 182.

8. Triple Entente: An informal understanding agreed by The Russian Empire, The Third French Republic and Great Britain, which served as counterweight to the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, 1914-1918.

9. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 182.

10. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 182.

11. Ibid. Pages 48-49.

12. Stevenson, David. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. New York: Basic Books, 2004. Page 14.

13. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 181.

14. Ibid. Page 178.

15. Splendid Isolation: Foreign policy guidance preventing the British Empire to entangled itself in continental alliance systems and to military agreements, under the formal objective to remaining active in the high seas.

16. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Pages 178-180.

17. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Pages 183.

18. Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Random House, 1987. Page 203.

19. Stevenson, David. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. New York: Basic Books, 2004. Page 70.

20. Stevenson, David. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. New York: Basic Books, 2004. Page 15.

21. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 212.

22. Stevenson, David. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. New York: Basic Books, 2004. Page 15

23. Sir Eyre Alexander Crowe (30 July 1864 – 28 April 1925) was a British diplomat and a leading expert on Germany in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Best known for his vigorous warning, in 1907, that Germany’s expansionist intentions toward Britain were hostile and had to be met with a closer alliance (“Entente”) with France.

24. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Memorandum_on_the_Present_State_of_British_Relations_with_France_and_Germany. Accessed on 02/03/2020.

25. Mahan, Sir Alfred Thayer. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History: 1660–1783. Little Brown and Company. Boston. (1890).

26. Motive of war; herein, seen as actions by an actor perceived to have initiated war.

27. After Alfred Von Schlieffen (Chief of the General Staff of the German Army from 1891 to 1906). In 1905 and 1906, Schlieffen devised an Army deployment plan for a decisive war-winning offensive against the French Third Republic.

28. Kossmann, E. H. (1978). The Low Countries, 1780–1940. History of Modern Europe. Oxford University Press. (1st ed.).

29. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 205.

30. The Treaty of London of 1839 was a treaty signed on 19 April 1839 between the European great powers, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Belgium. Also known as the First Treaty of London, the Convention of 1839, and the London Treaty of Separation.

31. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Page 213.

32. Keegan, John (2000). The First World War. Vintage. p. 48. ISBN 0-375-70045-5.

33. Willibald Krain. (1914). Kladderadatsch. Der Stänker

34. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p04ndbk3 (accessed on April 1, 2017).

35. http://www.businessinsider.com/maps-explain-south-china-sea-2017-3, (accessed on April 1, 2017).

36. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB986149564452369050, (accessed on April 1, 2017).

37. https://news.usni.org/2020/03/12/navy-considers-reversing-course-on-arleigh-burke-class-life-extension

38. H.I. Sutton. Aerospace & Defense. Forbes. (2019). https://www.forbes.com/sites/hisutton/2019/12/15/china-is-building-an-incredible-number-of-warships/#716fe39c69ac. Accessed on 28/03/2020.

39. R. O’Rourke. 2020. China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files, accessed on 28/03/2020.

40. R. O’Rourke. 2020. China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files, accessed on 28/03/2020.

41. Clausewitz, Carl von. On War. Translated by Col. J.J. Graham (1832), available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1946/1946-h/1946-h.htm

42. Klemens Von Metternich, Austrian statesman, minister of foreign affairs (1809–48), he is credited with helping achieve the alliance against Napoleon I, and the restoration of Austria as an European power

43. Kissinger, Henry. A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the problem of Peace, 1822-22. Friedland Books.2017.

Featured Image: The 2nd Squadron of the German High Seas Fleet sails to the North Sea. (Wikimedia Commons, colorized by Irootoko Jr.)

This seems more another of the many pro-British apologia out there rather than a serious attempt to illuminate the naval arms race and the resulting Anglo-French Naval Entente that may have brought Britain into the war without Germany’s catastrophic mistake in invading Belgium and her unforced errors committing atrocities during that invasion. Germany bears the majority of war guilt, but that does no let Britain, nor Russia and France completely off the hook–to say nothing of Austria-Hungary and Serbia.

The Anglo-French naval entente, we must remember, was under the care and keeping of the very bellicose First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, when the July 1914 crisis occurred. It would have been useful for the author to have examined Churchill’s actions in the naval endgame. As it was he, and the Royal Navy, mishandled the Goeben and Breslau affair.

There is a real need to examine this subject closer, but for those wishing a more detailed look can be found in Jon Sumida’s In Defense of Maritime Supremacy, but be advised, it is a dense read.

Another key book is Planning Armageddon by Nicholas Lambert.

John T. Kuehn, Ph.D. Naval War College

Dear professor Kuehn,

I cannot thank you enough for dedicating a portion of your valuable time to read this article, while I am not convinced and certainly do not share your particular stance on the subject, I do value and respect your opinion, however labeling the article “as another British apologia” -which is not, does not dismiss my claim that it was bad politics (Strategic level – foreign policy) on behalf of Germany as well as the series of cascading events that followed what constituted the real cause of the Great War, rather than the Anglo-german naval armsrace itself.

Anyhow, I thank you for your valuable input, as well as the sources you provided, rather than feeling discouraged by your comments, I will continue to further my readings on the subject.

Thank you

Capt Alcantara

History certainly has lessons for us from the past, but I do not think the US and China are gearing up for a Battle of Jutland.

While the US worries about “great power competition” by dusting off ideas from almost a century ago, China militarized a string of island bases in the South China Sea and “communized” Hong Kong; and Russia annexed part of Ukraine, including the Kerch Strait and its prized access to the Black Sea.

We are so focused on fighting the Next Big War that we will turn around one day and find its objectives have already been “won without fighting,” to quote Sun Tzu.

I quasi agree with your past comment, but today’s invasion of Ukraine by Russia (with obvious Chinese consent) tells us a different story. Russia is trying to reshape the world order based on its historical superpower condition over its influence domain (former USSR members leaning towards the West) and thus will attempt to reduce NATO’s influence sphere. What makes the situation worrisome is that the only feasible alternative to diplomacy seems to be nuclear escalation, which must be avoided at all cost, for no superpower would benefit from it, for the social price fro mankind would be unbearable.