By Reuben Keith Green

The hidden story of the U.S. Navy’s first Black commissioned officer spans five decades, three continents, two world wars, two wives from different countries, and one hell of a journey for an Indiana farm boy. For mutual convenience, both he and the United States Navy pretended that he wasn’t Black. This story had almost been erased from history until the determined efforts of one of his extended relatives, Jeff Giltz of Hobart, Indiana, brought it to light.1

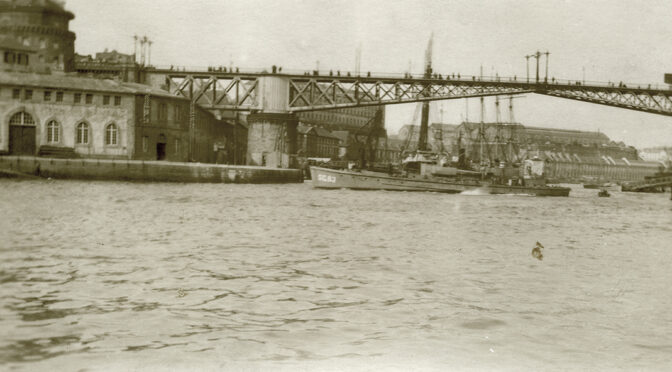

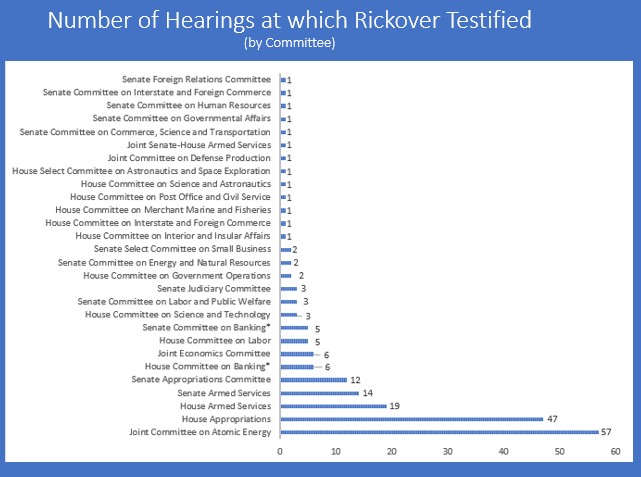

From before World War I until after World War II, leaders in the U. S. government and Navy would make decisions affecting the composition of enlisted ranks for more than a century and that still echo in officer demographics today. Memories of maelstroms past reverberate in today’s discussions regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), affirmative action in the military academies, meritocracy over so-called “DEI Hires,” who is and is not Black, and in renaming – or not – bases and ships that honor relics of America’s discriminatory and exclusionary past. Before Doris “Dorie” Miller received the Navy Cross for his actions on December 7th, 1941, and long before the Navy commissioned the Golden Thirteen in 1945, Lieutenant (junior grade) William Lloyd Garrison Payne was awarded the Navy Cross for the hazardous duty of commanding the submarine chaser USS SC-83 in 1918. While his Navy Cross citation is sparse, the hazards of hunting submarines from a 110-foot wooden ship were considerable. His personal and professional history, still emerging though it may be, reveals much about the nation and Navy he served and deserves to be revealed in full. Understanding the racial and political climate during which he received his commission is crucial to understanding the importance of his place in Navy history.

Quietly Breaking Barriers

William Lloyd Garrison Payne was born on Christmas day in 1881 to a White Indiana woman and a Black man, and completed forty years of military service by 1940 – before volunteering for more service in World War II. Garrison Payne’s virtual anonymity, despite his groundbreaking status as the first Black naval officer and a Navy Cross recipient, stemmed from pervasive racial discrimination, manifested in political and public opposition (notably by white supremacist politicians like James K. Varner and John C. Stennis), and internal resistance within the Navy. His long anonymity exemplifies a failure to learn from the past.2

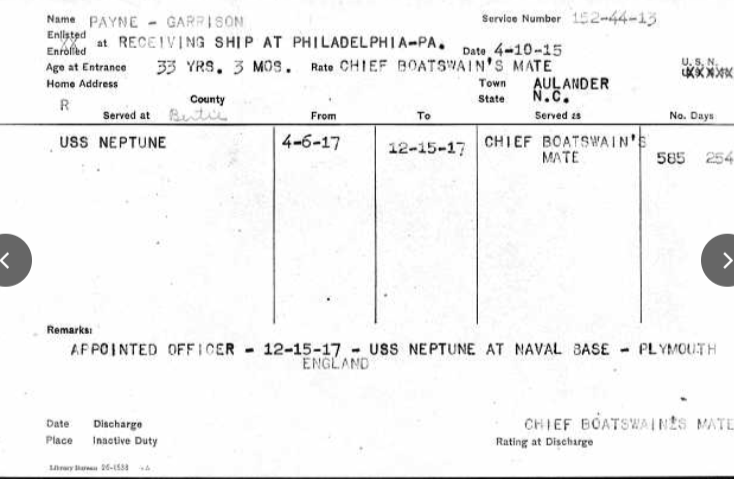

Garrison Payne, or W.G. Payne, served in or commanded several vessels and had multiple shore assignments during his five-decade career. His officer assignments include commanding the aforementioned USS SC-83 and serving aboard the minesweeper USS Teal (AD-23), the collier USS Neptune (AC-8), submarine chasers Eagle 19 and Eagle 31, which he may have also commanded, and troop ship USS Zeppelin. He had a lengthy record as a Chief Boatswain’s Mate (Chief Bos’n).

After his commissioning in Plymouth, he presumably stayed in England and later took command of the USS SC-83 after she transited from New London, Connecticut to Plymouth, England in May 1918.

Garrison Payne took Rosa Manning, a widow with a young daughter, as his first wife in 1916. The 1910 North Carolina Census records indicate that she was the daughter of Sami and Annie Hall, both listed as Black in the census records. Later census records list Rosa Payne as White, and using her mother’s maiden name (Manning), as she did on their 1916 marriage license. His race was also indicated as White on the license, and his parents listed as Jackson Payne and Ruth Myers (Payne), his maternal grandparents.

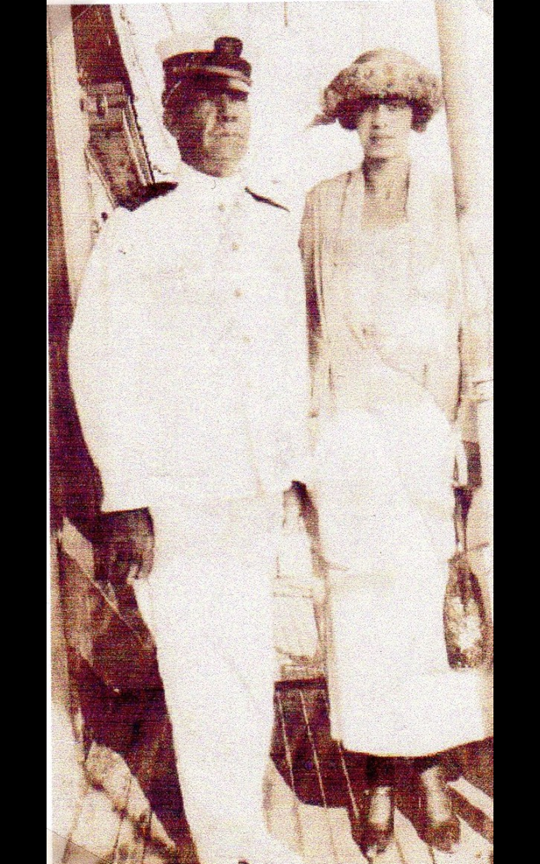

In the photo above, Payne, wearing the rank of lieutenant, stands beside an unidentified Black woman, who may be his wife. He brought back Mary Margaret Duffy from duty in Plymouth, England on the USS Zeppelin, a troop transport, in 1919, listing her on ship documents as his wife. He used various first names and initials to apparently help obscure his identity.

Jeff Giltz of Hobart, Indiana is the great grandson of Gertrude “Gertie” Giltz, Garrison’s half-sister by the same mother, Mary Alice Payne. She was unmarried at the time of his birth in 1881. Her father, Jack Payne was the son of a Robert Henley Payne, who traveled first from Virginia to Kentucky, and then settled in Indiana, may have been mixed race. During the U.S. Census, census takers wrote down the race of household occupants as described by the head of the household. Many light-skinned Blacks thereby entered into White society by “turning White” during a census year. It is unknown when Garrison made his “transition” from Black or “Mulatto” to White.

None of Garrison’s half-siblings, who were born to his mother after she married Lemuel Ball, share his dark complexion. When she married, Garrison was sent to live nearby with his uncle, William C. Payne, whose wife was of mixed race. In the 1900 Census, Garrison is listed as a servant in his uncle’s household, not his nephew.

Taken together – Garrison Payne’s dark skin, the fact that the identity of his father was never publicly revealed and that he was born out of wedlock with no birth certificate issued, that he was named for a famous White Boston abolitionist and newspaper publisher,3 that his White mother gave him her last name instead of his father’s, that he was sent away after his mother married, and the oral history of his family – all point to the likelihood that Garrison Payne was Black.

In the turn of the century Navy, individuals were sometimes identified as “dark” or “dark complexion” with no racial category assigned. Payne self-identified as White on both of his known marriage licenses. According to Jeff Giltz, there are many references to Garrison Payne in online genealogy, military records and newspaper sites, but none appear on the Navy Historical and Heritage Command (NHHC) website. His military service likely began in 1900.

Rolling Back Racial Progress during Modernization

In his 1978 book Manning the Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1898-1940, former U.S. Naval Academy Associate Professor Frederick S. Harrod discusses several of the policies enacted during that period that helped shaped today’s Navy.4 He describes how the famously progressive Secretary of the Navy (1913-1919) Josephus Daniels, otherwise notorious for banning alcohol from ships, brought Jim Crow policies to a previously partially integrated Navy (enlisted ranks only) and banned the first term enlistment of Negro personnel in 1919, a ban that would last until 1933. No official announcement of the unofficial ban was made, but Prof. Harrod asserts that it was instituted by an internal Navy Memorandum from Commander Randall Jacobs, who later issued the Guide to Command of Negro Personnel, NAVPERS-15092, in 1945. President Woodrow Wilson and Daniels were both staunch segregationists and White supremacists. The Navy became more rather than less racially restrictive during the Progressive Era because of the lasting effects of both Secretary Daniels and President Wilson.

The number of Negro personnel dropped from a high of 5,668 in June of 1919 – 2.26% of the total enlisted force – to 411 in June of 1933, a total of 0.55% of the total force of 81,120 enlisted men. Most of the Black sailors were in the Stewards Branch, and most were low ranking with no authority over White sailors, despite their many years of service and experience. Those very few “old salts” outside that branch, like Payne, were difficult to assign, as the Navy did not want them supervising White sailors, despite their expertise and seniority.

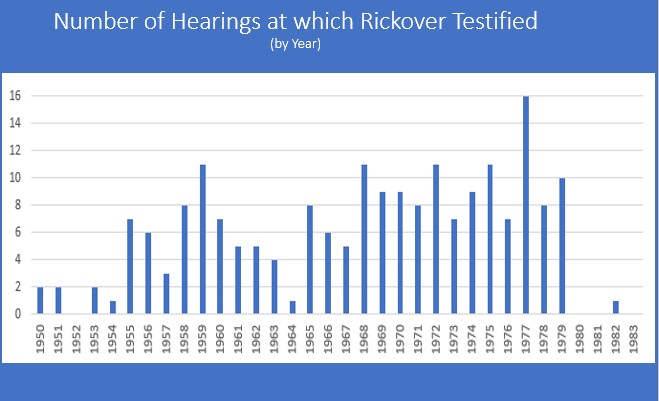

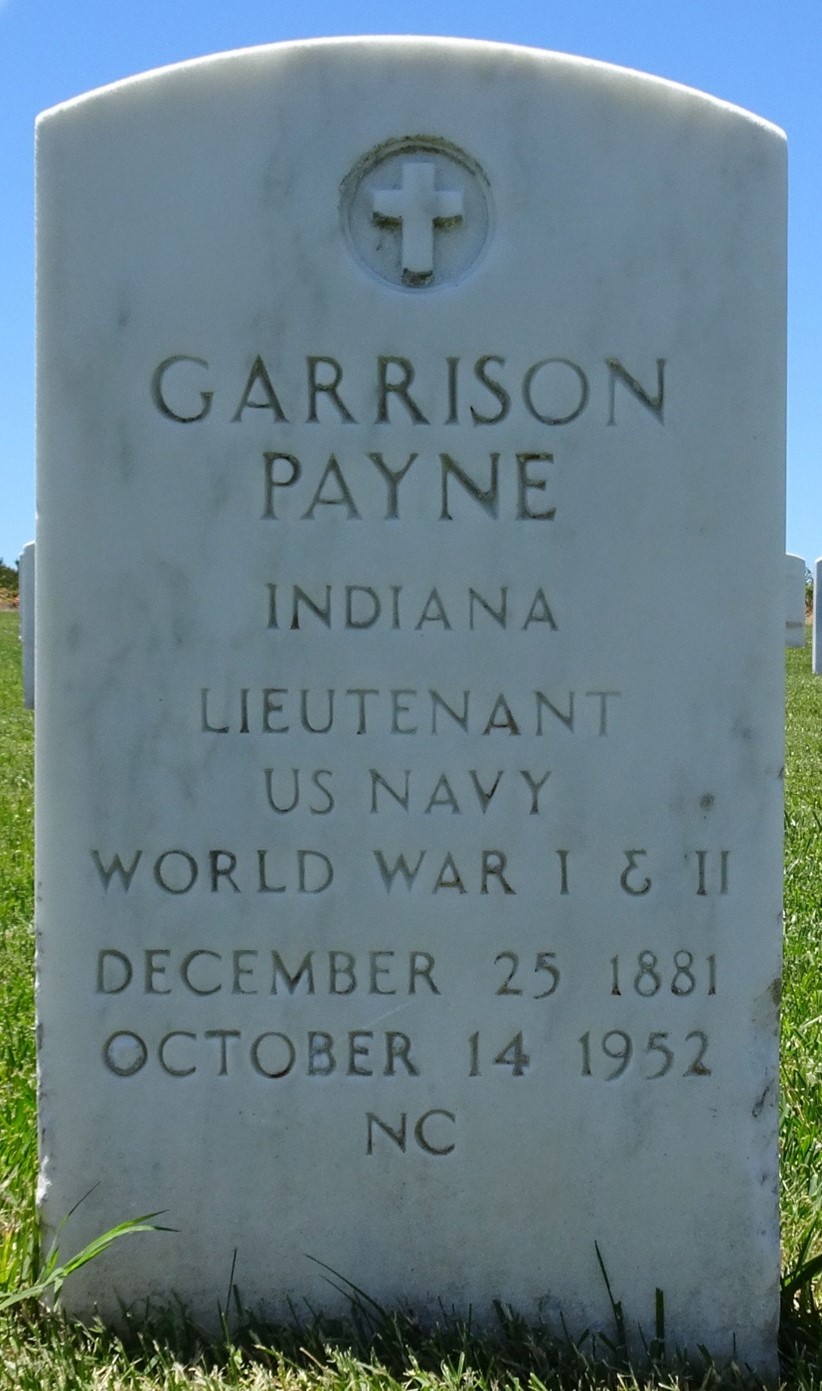

Following his temporary promotion to the commissioned officer ranks – rising as far as lieutenant on 01 July 1919 – Garrison Payne was eventually reverted to Chief Bos’n, until he was given an honorific, or “tombstone”, promotion to the permanent grade of lieutenant in June of 1940, just before his retirement. Payne died on 14 October 1952 in a Naval Hospital in San Diego California, and was interred in nearby Fort Rosacrans National Cemetery on 20 October 1952, in Section P, Plot P 0 2765 – not in the Officer’s Sections A or B, despite being identified as a lieutenant on his headstone. Garrison Payne’s hometown newspaper’s death notice indicates that he was the grandson of Jack Payne, with no mention of his parents. A handwritten notation on his Internment Control Form indicates that he enlisted on 31 March 1943, making him a veteran of both world wars, as also reflected on his headstone. His service in World War II – as a volunteer 62-year-old retiree – deserves further investigation.

The Navy reluctantly commissioned the Golden Thirteen in 1945 only because of political pressure from the White House and from civil rights organizations like the NAACP, led by Walter F. White, the light-skinned, blond-haired, blue-eyed Atlanta Georgia native who embraced his Black heritage. Unlike Walter White, though, Garrison Payne likely hid his mixed-race heritage to protect his life, his family, and his career. When he married Mary Margaret Duffy in 1937, at the age of 54, he travelled more than 170 miles from San Diego, California to Yuma, Arizona to do so. Why? His new wife, Mary Margaret Duffy, was 37, and an immigrant from Ireland. He had previously listed her as his wife when he transported her to America in 1919. Are there records of this marriage overseas? Would that interracial marriage have been recognized, given that interracial marriage would remain illegal in both states for years to come? On their marriage certificate, as with Payne’s first marriage certificate, both spouses are listed as White.

The Navy’s Circular Letter 48-46, dated 27 February 1946, officially lifted “all restrictions governing the types of assignments for which Negro naval personnel are eligible.” Despite that edict, and President Truman’s Executive Order desegregating the armed forces in 1948, it would be decades before the Navy’s officer ranks would include more than fifty Blacks.

The stories of several early Black chief petty officers are missing from the Navy’s Historical and Heritage Command’s website, though it does include the story of a contemporary of Payne’s, Chief Boatswain’s Mate John Henry “Dick” Turpin, a Black man. That Payne, a commissioned officer, is absent and unrecognized can be attributed to at least five possible reasons.

The first is that the Navy didn’t know of his existence, significance, or accomplishments. Table 5 in Professor Harrods’s book is titled “The Color of the Enlisted Forces, 1906 – 1940,” and is compiled from the Annual Reports of the Chief of Navigation for those years, with eleven different racial categories, including “other.” Where Garrison Payne fell in those figures during his enlisted service is uncertain, but he was present in the Navy for each of those year’s reports.

The second is that Payne had no direct survivors to tell his story, and no one may have asked him to tell it. He and his first wife Rosa likely divorced sometime after the death of their only child. It is unknown if his Irish-born wife Mary Margaret produced any children by Garrison.

The third reason could be that the Navy may have kept his story quiet for his own protection, and that of the Woodrow Wilson administration and the Indiana political leadership. Garrison Payne was commissioned by the same President Woodrow Wilson who screened the movie Birth of a Nation at the White House in 1915, re-segregated the federal government offices in Washington DC, refused to publicly condemn the racial violence and lynching during the “Red Summer” of 1919, and whose Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, was one of the masterminds behind the 1898 Wilmington Insurrection, which violently overthrew an elected integrated government in Wilmington, North Carolina. Acknowledging Payne as a decorated and successful Black naval officer would have been an embarrassment to Wilson, Daniels, and undercut their political and racist agendas.

Black veterans were specifically targeted after both world wars, by both civilians and military personnel, to reassert White supremacy. Payne was from Indiana, where the Ku Klux Klan was revived in 1915, and became a very powerful organization in the 1920’s. Such organizations may have sought out and harassed Payne and his family, had they known that this Black Indiana farm boy, born to a White mother, had not only received a commission in the U.S. Navy but had commanded White men in combat.

The fourth reason is that the Navy may have wanted to hide his racial identity. His record of accomplishment as a Navy Cross recipient and ship’s C.O. would have undermined the widespread belief that Black men could not perform successfully as leaders, much less decorated military officers. He was not commissioned as part of some social experiment or social engineering, but because the Navy needed experienced, reliable men to man a rapidly-expanding fleet and train inexperienced crews. Garrison Payne did just that, during years of dangerous duty at sea.

The fifth reason may be that Payne recognized the benefits of passing for White to his life and career, which may have compelled him to do so. He was raised in a largely white society, by white-appearing relatives. Had he not successfully “passed,” he likely would not have been commissioned.

Regardless of the reasons in the past, it is now time to herald the brave naval service of Garrison Payne. The Navy Historical and Heritage Command, the Smithsonian Institution, the Indiana Historical Society, the Hampton Roads Navy Museum, and others should work together to bring his amazing story out of the shadows.

Why Garrison Payne’s Story Matters

For years, many Black naval officers have searched in vain for stories of their heroic forebearers. Actions taken by politicians regarding nominations to military academies for much of the 20th century helped ensure that Black military officers remained a rarity, particularly those hailing from Southern states.5 The life story of Lieutenant Garrison Payne needs to be thoroughly documented and publicized because representation matters. On a personal note, knowing of his story while I was serving as one of the few Black officers in the Navy would have inspired me immensely. Garrison Payne served as likely the only Black officer in the Navy for his entire career. He showed what was possible. Heralding his trailblazing career can only positively impact the discussions about the future composition of the U.S. Navy’s officer corps as it inspires generations of sailors. Historians and researchers should continue the work of archival research to gain a fuller understanding of his story and significance. My hope is that veteran’s organizations and national institutions such as the Smithsonian Institution begin the effort to flesh out the story of Lieutenant Garrison Payne.

Reuben Keith Green, Lieutenant Commander, USN (ret) served 22 years in the Atlantic Fleet (1975-1997). After nine years in the enlisted ranks as a Mineman, Yeoman, and Equal Opportunity Program Specialist, he graduated from Officer Candidate School in 1984 and then served four consecutive sea tours. Both a steam and gas turbine qualified engineer officer of the watch (EOOW), he served as a Tactical Action Officer (TAO) in the Persian Gulf, and as executive officer in a Navy hydrofoil, USS Gemini (PHM-6). He holds a Master’s degree from Webster University in Human Resources Development, and is the author of Black Officer, White Navy – A Memoir, recently published by University Press of Kentucky.

Endnotes

1. Except as otherwise cited, research in this article is based on documents in the author’s possession and oral history interviews with Mr. Jeff Giltz.

2. War and Race: The Black Officer in the American Military. 1915-1941, 1981, Gerald W. Patton, Greenwood Press

3. All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery, 2008, Henry Mayer, W. W. Norton and Company

4. Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940, 1978, Frederick S. Harrod, Greenwood Press.

5. The Tragedy of the Lost Generation, Proceedings, August 2024, VOL 150/8/1458, John P. Cordle, Reuben Keith Green, U.S. Naval Institute.

Featured Image: SC 83 underway, steaming under a bridge. (Photo via Subchaser.org)