By David Scott

French maritime strategy has been on full public display with the deployment of the French Carrier Strike Group (CSG) from November 2024 to April 2025, carrying out an extended deployment across the Indo-Pacific in the furthest ever Operation Clemenceau.

The French Carrier Strike Group included various components:

- FS Charles de Gaulle: nuclear-powered aircraft carrier

- FS Forbin: air defense destroyer,

- FS Provence: anti-submarine frigate,

- FS Alsace: air defense frigate

- FS Duguay-Trouin: nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN)

- FS Jacque Chevallier: logistics support ship

- Loire-class offshore support and assistance vessel

The air wing included 22 Rafale Ms, two E-2C Hawkeye Airborne Early Warning (AEW) aircraft, and three helicopters. The CSG, commanded by Rear Admiral Jacques Mallard, left Toulon on November 28.

The planned operation had been denounced in the Chinese state media, in the Global Times on November 4, under the headline “French aircraft carrier’s planned deployment panders to NATO’s expansion into Asia-Pacific.”

Initially the French CSG was deployed in the Eastern Mediterranean, where France, like Italy, has concerns over Russian basing in Libya. It was initially accompanied for escort duties in the Mediterranean by the Italian frigate ITS Virginio Fasan. The CSG then transited the Suez Canal on December 24 and on April 10. The Houthis did not interfere in the CSG’s transit on its way to and from the Indian Ocean.

Strategic Interests

France is a resident state in the Indo-Pacific, with around 1.5 million French citizens inhabiting its overseas territories of Mayotte, La Reunion, New Caledonia and French Polynesia. These parts of France are located south of the Equator, spread across the southern reaches of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and are key to France having the second largest Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), with 90 percent of it located in the Indo-Pacific. Freedom of navigation and Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOCs) are wider concerns for France in the northern reaches of the Indo-Pacific, under threat from Houthis in the Red Sea and China in the South China Sea. Maritime cooperation and maritime partnerships with other countries has been a particular feature of French strategy. France’s President led from the top in visits to Australia and New Caledonia in 2018 where Macron talked of an “Indo-Pacific axis” (l’axe Indo-Pacific) amongst China-concerned states; amongst which “France is a great power (une grande puissance) of the Indo-Pacific.”

French maritime strategy for the Indo-Pacific has focused around three planks. First are its maritime holdings in the southern reaches of the Indo-Pacific (principally Reunion, New Caledonia, and French Polynesia), and the base in Djibouti. Second are deployments from metropolitan France. Third are varied strategic partnerships around the northern reaches of the Indo-Pacific (principally India and Japan) region. The latter two were very much on show with the deployment of its Carrier Strike Group for Operation Clemenceau.

Maritime interests require maritime assets to defend and maintain them. Here the French Navy is the only European navy, along with the British Royal Navy, that has a full spectrum of capabilities, including nuclear-powered submarines, surface combatants, amphibious ships, maritime patrol aircraft, and an aircraft carrier.

Carrier Capability

The nuclear-powered Charles de Gaulle is the flagship of the French Navy. The ship, commissioned in 2001, is catapult-equipped for its three squadrons of Dassault Rafale M warplanes, which also allows for operations by U.S. Super Hornets. Its full load displacement is 42,500 tons, surpassing France’s earlier and conventionally-powered aircraft carriers, the Clemenceau and the Foch, which served from 1961 to 2000 and had a full load displacement of 32,780 tons.

With the successful construction of the Charles de Gaulle, there was initial consideration during the 2000s of building a second aircraft carrier, to be called the Richelieu, in collaboration with U.K. designs being used for the construction of HMS Queen Elizabeth. However, that co-development route was abandoned in 2008, and the 2013 French Defense White Paper likewise abandoned the pursuit of a second French carrier. In retrospect, might this have been a strategic error in force design?

Instead, attention eventually turned to a long-term replacement of the Charles De Gaulle. Macron’s announcement in 2020 was for another nuclear-powered New Generation Aircraft Carrier (Porte-avions de nouvelle generation, or PA-NG) which leaves France as a one-carrier navy. Nevertheless, this represents a jump in capacity, a super-carrier of 75,000 tons displacement, that was also longer and wider than the Charles de Gaulle. The main construction and assembly is envisaged between 2032-2035 with initial sea trials on nuclear power in early 2036. If this timetable can be met, then the ship is scheduled to commission in 2038, ready for the de-commissioning of the Charles De Gaulle.

Work has already started on the new French super-carrier. The commitment to the program was demonstrated by the placing of contracts for long lead items in April 2024. This included elements of the nuclear propulsion system and preparatory infrastructure work at the Chantiers de l’Atlantique shipyard. General Atomics landed a $41.6 million contract in December 2024 to design cutting-edge Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) for the envisaged carrier.

With regard to general French maritime strategy the Charles de Gaulle is a particularly powerful aircraft carrier, its nuclear propulsion nature unmatched in Europe where the U.K. (HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales), and Italian aircraft carriers (ITS Cavour) remain conventionally powered. Only the U.S. has nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, 11 in all: CVN-68 to CVN-78, made up of 10 Nimitz-class carriers and one Gerald R. Ford-class carrier.

However, France remains hampered by its single status aircraft carrier, powerful though it is. China, India, and the U.K. have two aircraft carriers, which enables one to remain active while the other is refitted and maintained. The Charles de Gaulle’s mid-life refit between February 2017 and September 2018 removed her from operations for 18-months. Given this limitation, the French Navy’s decision to deploy this sole carrier to the Indo-Pacific for five months is all the more significant.

Aims of Operation Clemenceau

The operation was announced in November 2024. Rear Admiral Jacques Mallard announced that the deployment had “4 main objectives:”

(1) First of all, contribute to national and European operations in the Red Sea and in the Indian Ocean. These operations are meant to strengthen the maritime security in the area.

(2) To develop interoperability with partners and allies in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

(3) To promote through this deployment a free, open and stable Indo Pacific with our regional partners in the frame of international law.

(4) Finally, to contribute to the protection of our population and of our interests in the Indo Pacific where France is a coastal nation, and it must exercise its sovereignty on all its overseas territories.

In going across the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific various exercises were carried out with various partners and allies in the northern reaches of the Indo-Pacific, in effect a focus on objectives 3 and 4. However, in actually not deploying to French possessions in the southern reaches, the CSG did not particularly meet objective 4, where local forces continued to maintain French presence.

Activities of Operation Clemenceau

Operations with India were in two phases. The first was after friendly port call at Goa, the CSG carried out varied exercises off Kochi on January 9. Tactical evolution maneuvers were carried out by the CSG with INS Mormugao, during which the fleet replenishment tanker FNS Jacques Chevallier refueled the Indian vessel; while Rafale fighters from the Charles de Gaulle carried out joint anti-aircraft drills with Indian Sukhoi and Jaguar fighters.

Operations in the Indonesia Sea commenced with a historic port call at Jakarta, the first ever by a French carrier. This was followed by the 5th iteration of the multinational exercise La Perouse, from January 16-24, in which the French CSG led maritime security and cooperation drills with the Indian, Australian, Canadian, U.K. and U.S. navies. In addition to these established partners and allies, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore participated in La Perouse for the first time.

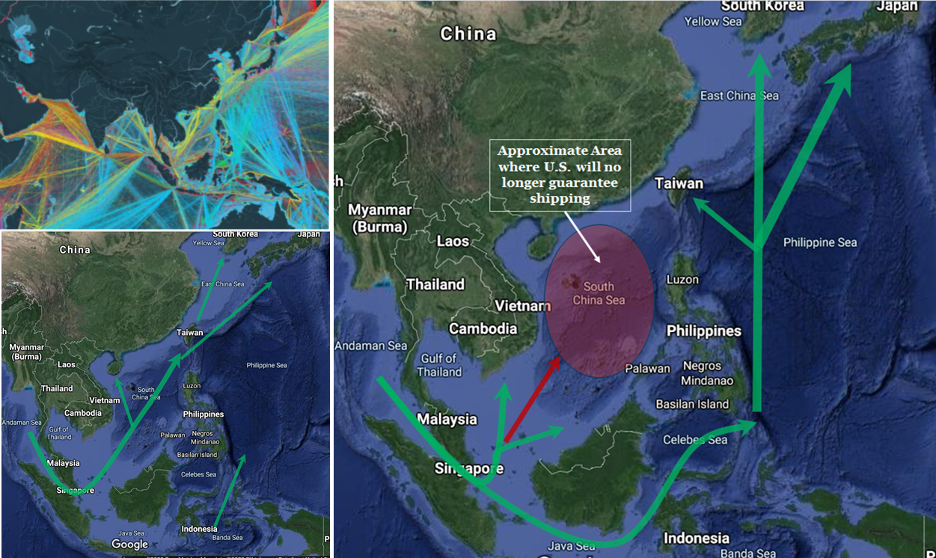

La Perouse was divided into three components, in the Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok straits locations reflecting the French mission statement that the exercise was designed and located “to secure strategic maritime lines.” The Malacca Strait phase ran from Thursday to Sunday, with the Forbin drilling first with RMN corvette KD Lekir (FSG26), training ship KD Gagah Samudera (271), an RMN fast combat boat, and two Royal Malaysian F/A-18D Hornet fighters in the Malacca Strait. These drills included a simulated local air-defense exercise, a surface firing exercise, and an advance interdiction and boarding exercise. The Forbin then conducted drills with the Singapore littoral mission vessel RSS Independence in the Singapore Strait, which joins the Malacca Strait’s southern exit. The Jacques Chevalier also pulled into Singapore for a logistical stop. In the Sunda Strait phase Indonesia provided base support for two French Navy Atlantique 2 maritime patrol aircraft (MPAs) participating in La Perouse, which had arrived on January 11, after a four-day trip from Lann-Bihoue naval air base in France with a logistics stopover in India.

The largest part of the exercise, the Lombok Strait phase, involved the CSG drilling with established partners. Commanding officers from Australia’s destroyer HMAS Hobart, the Canadian frigate HMCS Ottawa, India’s destroyer INS Mumbai, the U.K. offshore patrol vessel HMS Spey and the U.S. Littoral Combat Ship USS Savannah gathered aboard the carrier Charles De Gaulle on Saturday for a pre-exercise meeting. This six-state format was yet another permutation within the flexible Indo-Pacific strategic geometry that has evolved in response to China. Further spin-offs from the Carrier Strike Group were the friendly port call of the Forbin and Provence to Bali from January 28 to February 3, and the Jacque Chevallier to Darwin on February 4.

The next event for Operation Clemenceau was the CSG participation in Exercise Pacific Steller 2025, a Multi-Large Deck Event (MLDE) hosted by the French Navy in the Philippine Sea from February 8-18. For this first iteration, 14 units from the three participating nations deployed in the Philippine Sea. The French CSG was joined by the Japanese Self Defense Force’s JS Kaga helicopter carrier and the destroyer JS Akizuki, and by the American aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson, the destroyers USS Princeton, USS Sterett, and USS William P. Lawrence, and one P-8A maritime patrol aircraft.

This tri-carrier exercise was visually striking, and the first of its kind between the three states. The high-level training drills included anti-submarine warfare, air defense, cross-decking aircraft, and replenishment at sea exercises. Cross-deck operations included F/A-18F Super Hornets and a CMV-22B Osprey from Carl Vinson landing on and taking off from Charles De Gaulle. In turn, Charles De Gaulle’s embarked Rafale fighters landed on and launched from Carl Vinson. The Jacques Chevalier performed a replenishment at sea for the Kaga, Princeton, and Sterret.

This high-powered trilateral carrier exercise was criticized in the Chinese State media, on February 9 in the Global Times, under the headline “Steller 2025 exercise shows Philippine attempts to expand foreign military presence in SCS.” The North Korean state-state Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) also denounced the trilateral exercise as involving “foreign invasion forces.” France responded by sending the frigate Alsace and oiler Jacque Chevallier from the CSG to Okinawa on February 13 to help in monitoring operations in support of U.N. sanctions on North Korea. One of the Atlantique 2 maritime patrol aircraft dispatched for La Perouse were also sent on to Okinawa.

The next stop for the CSG was the South China Sea, where the CSG paid a port call to Subic Bay (Manila) on February 23. Its significance was three-fold. Firstly, this was the first ever appearance in the Philippines by a French aircraft carrier. Secondly, this visit was preceded by the largest bilateral drill between the two sides. Thirdly, the exercising with the Philippine Navy took place in the South China Sea waters off Western Luzon in the Philippine EEZ. The exercising involved the French CSG, the Philippine flagship BRP Jose Rizal and BRP Gregorio del Pilar, as well as French Rafale and Philippine FA-50PH fighter jets. Their exercise focused on aerial and anti-submarine warfare. This was a deliberate signal to Beijing and an equally measure of support to the Philippines which had faced rising Chinese pressure over the South China Sea during 2024. French trilateral exercising with the US and the Philippines in the South China Sea the previous year had been denounced in China.

The Provence was detached from the French CSG to carry out a week-long visit to Ho Chi-Minh City from March 1-7. Port call visits were combined with joint maritime search and rescue missions off the Vietnamese coast.

The final substantive operation for Operation Clemenceau, following friendly port calls at Singapore and Colombo, was the bilateral Varuna exercise with India from March 19-22. This involved dual carrier operations between the French Charles de Gaulle CSG and the India INS Vikrant CSG. This second round of exercising with India was an indication of the particularly strong maritime links developing between France and India.

Local Assets

Part of French maritime strategy is to base units in its island territories, and from there deploy around the Indo-Pacific. This is a complement to the periodic more powerful deployments from the French metropolitan waters, witnessed with the CSG between November 2024 and March 2025.

FNS Floreal was dispatched for CTF-150 operation in the Arabian Sea, for Eagle Claw One and Eagle Claw Two in November and December 2024, alongside Pakistan’s PNS Zulfiquar. Even as the CSG was operating in the Western Pacific in Pacific Steller, the French frigate FNS Vendemiaire (based at New Caledonia) docked in Denpasar, Bali, on February 14 as part of its participation in the multilateral exercise Komodo hosted by the Indonesian Navy from February 14-17. Spring 2025 witnessed the Prairial visiting various places in the South Pacific, including the Cook Islands on February 27, whose government welcomed the visit as “strengthening regional security efforts” and demonstrating “Pacific solidarity.” The context for this is Chinese penetration of South Pacific island states. In a tidy local division of labor, the 2-yearly Southern Cross exercise hosted by France at Wallis and Futuna Islands from April 22 to May 3 brought together forces from Fiji, Tonga, Papua New Guinea, Australia, and New Zealand. Colonel Frederic Puchois, Chief of the Joint Staff in New Caledonia announced its purpose was to test French “capacity to project forces” from New Caledonia.

Political Underpinnings

The CSG deployment was not only complemented by ongoing use of local French assets, but also given political support from the highest level during 2025. In January Macron announced at the Ambassadors’ Conference that the Indo-Pacific “is obviously a priority for us.” Ministers also maintained this support.

India enjoys a very high profile for France, already indicated by the two rounds of exercises held by the CSG with India, in January and March. Strategic convergence was reflected in the 7th India France Maritime Cooperation Dialogue held in New Delhi on January 14. It was co-chaired by Shri Pavan Kapoor, Deputy National Security Advisor and Alice Rufo, Director General for International Relations and Strategy, Ministry for the Armed Forces. Their Joint Declaration recorded their common interest in freedom of navigation and need to “support free and secure access to sea lanes of communication.”

On January 28, the French Carrier Strike Group made a port call to Jakarta, to lead the La Perouse exercise. Three days later, on January 31, the French Minister of the Armed Forces, Sebastien Lecornu, flew into Jakarta to meet with President Prabowo Subianto, Indonesian Defense Minister Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin, and Foreign Minister Sugiono. In the Philippines, the French Joint Commander for Asia Pacific, Rear Admiral Guillaume Pinget, met with Lt. Gen. Jimmy Larida, Acting Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), at Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City on February 13, to push forward a Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA). The French Foreign Minister’s visit Jean-Noel Barrot’s visit to Indonesia on March 26 brought their signing of the Indo-Pacific Port Security Project. Finally, President Macron’s Keynote Address at the IIIS Shangri La Dialogue on 30 May, made during his state visit to Indonesia, re-emphasized French interest and commitment to the Indo-Pacific.

The French CSG deployment fits into this pattern of growing European maritime involvement in the Indo-Pacific during the past few years. Indeed, the 2023 U.K.-France Summit had agreed on “the sequencing of more persistent European carrier strike group presence in the Indo-Pacific.” In this vein, the Italian CSG deployment in the second half of 2024 was followed by French CSG deployment in the first half of 2025 and immediately followed by U.K. deployment in the second half of 2025. The French CSG group can be seen as a “force multiplier” in the Indo-Pacific, particularly in the event of a U.S.-China confrontation.

Uncertainties

It remains to be seen how far the downturn in U.S.-Europe cooperation witnessed in splits over Ukraine arising in Spring 2025 will affect European juggling of resources between the European and Indo-Pacific theaters. With Macron’s address on March 5 identifying Russia as a “threat to France and to Europe,” might France now focus on deploying in European waters rather than across the Indo-Pacific? In light of growing concerns about Russia and signals of American retrenchment from Europe, there may be a shift towards greater French focus on the Mediterranean, given Russian influence in Libya, and up to the Black Sea, in light of Russia’s continuing war against Ukraine. However, and perhaps crucially, France’s resident sovereignty and associated EEZ give France a continuing anchor in the Indo-Pacific, and interests to maintain, that other European actors do not have.

Dr. David Scott is an associate member of the Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies. A prolific writer on Indo-Pacific maritime geopolitics, he can be contacted at davidscott366@outlook.com.

Featured Image: April 25, 2024 – The French Navy carrier Charles de Gaulle off the coast of Toulon. (NATO photo)