By Dirk Steffen

Background

The Niger Delta Avengers (NDA) are Nigeria’s “new” Niger Delta militancy phenomenon. They have issued challenges to the Nigerian government, international oil companies, and the military. Within a span of less than 3 months they are believed to be primarily responsible for reducing Nigeria’s oil production from a (theoretical) 2.2m barrels per day to around 1.4m barrels per day by the end of May 2016. They have mainly targeted Nigerian state and international oil companies’ pipeline infrastructure with explosives attacks. The spectre of their involvement in maritime piracy and kidnappings has been raised as well.

There is very little evidence-based information on the NDA. Even the Nigerian security services are not totally sure what they are up against, although the group has made stock demands for Niger Delta autonomy, greater participation in the oil wealth, and cessation of environmental destruction. Former militants, the government, and other stakeholders variously blame former militant leader Tompolo, the opposition Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP), former President Goodluck Jonathan, and other ex-militants for being behind the group. The NDA themselves reveal little, except for their geographic origin: Warri South West local government area (LGA) in Delta state. So far they have run rings around the Nigerian military, avoiding direct confrontation and eluding arrests.

Although the area of operations west of Warri between the Benin and Forcados Rivers is a coastal strip only 30nm long and 30nm deep, it is a militarily challenging riverine and inshore environment of mangrove swamps and wetlands with no road infrastructure.

The NDA in the present form emerged in or around January 2016 and publicly claimed its first attack on 10 February on the Bonny Soku Gas Line, in Bayelsa state.

The NDA espouse the following military and political objectives:

- Cripple the Nigerian economy (‘Operation Red Economy’)

- Force the government to negotiate on their demands in a ‘sovereign national conference’

- Re-allocation of Nigerian ownership of oil blocs (in favour of Niger Deltans)

- Autonomy/self-determination for the Niger Delta

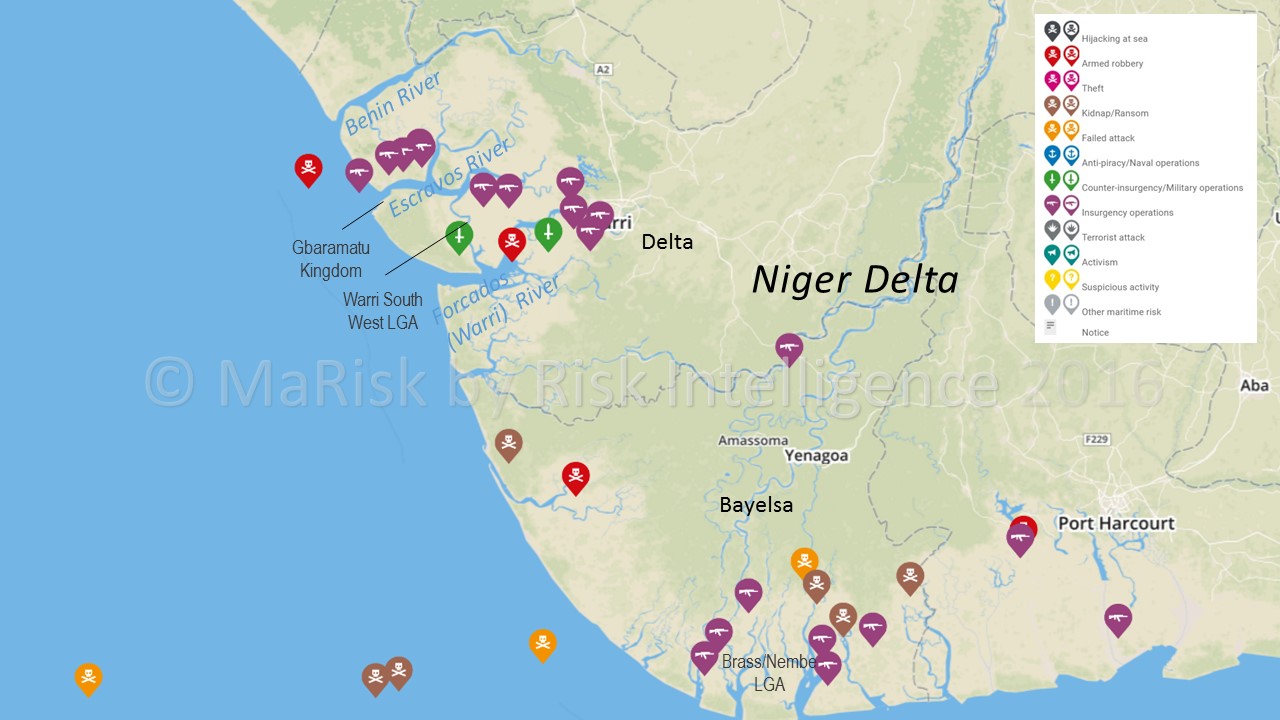

Some 21 attacks/clusters of sabotage took place against oil and gas infrastructure in the Niger Delta between 15 January and 10 June 2016. The NDA have directly claimed responsibility for 13 attacks/clusters of attacks between 10 February and 1 June 2016, nine of which were in the Warri/Escravos/Forcados area and four in the Brass/Nembe area. They have also retrospectively claimed responsibility for four further attacks between 15 January and 9 February (three in Warri/Escravos area and one in the Brass/Nembe area). Of the 17 attacks claimed by the NDA, 15 were in swamp/inshore areas, one was coastal (Forcados export pipeline on 10 February) and one was close offshore (Chevron Okan field valve platform). No one has been killed in the attacks on the oil and gas infrastructure; all targets were unmanned and unguarded. The NDA have not claimed responsibility for any kidnappings so far.

The hitherto unknown “Red Egbesu Water Lions” (Egbesu is an Ijaw war deity) claim association with the NDA and have also claimed responsibility for one attack in Bayelsa state (South Ijaw LGA), but there has been no reciprocal “acknowledgement” by the NDA. Two attacks (on 20 and 22 May –against the Escravos-Lagos gas line near Ogbe-Ijoh and Brass-Tebidaba pipeline), during the grace period of an NDA ultimatum are unclaimed. Additionally, on 9 June 2016, a Nigerian Petroleum Development Company crude oil pipeline line in Warri South West LGA was blown up by unidentified attackers.

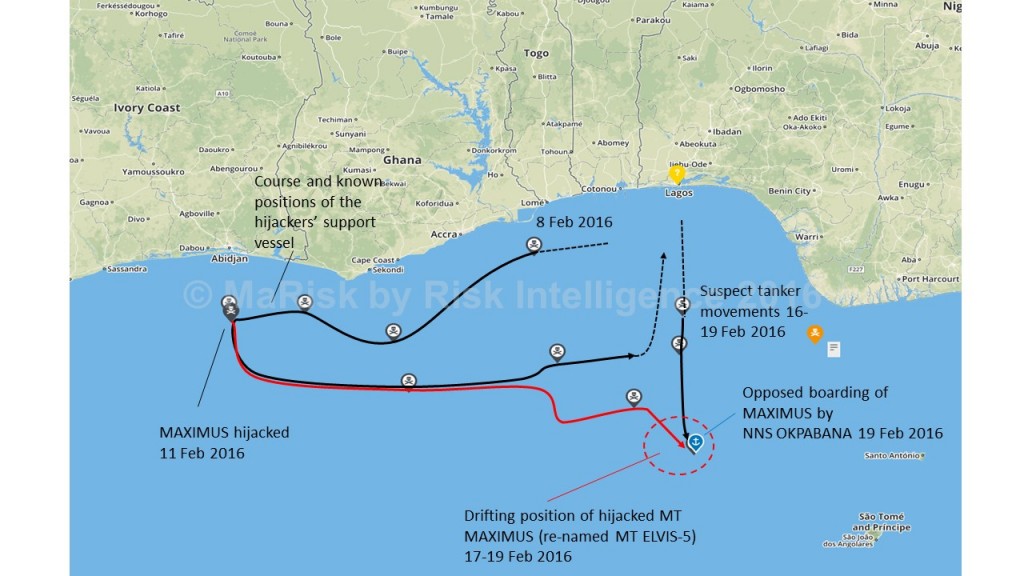

“General Ben” of the Concerned Militant Leaders (CML) claimed responsibility for the kidnapping of five crew members from the LEON DIAS on 31 January 2016; he later also claimed association with the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) movement (denied by IPOB and the Nigerian Army) and with NDA (not acknowledged by the latter). The NDA have not carried out (or claimed responsibility for) any maritime attacks, although they issued a warning to ship operators on 22 April 2016. In total, 15 individuals have been arrested so far by the Nigerian military in connection with the attacks, but their association with the NDA is unproven.

Assessment

The Nigerian government’s initial plan to simply disrupt the criminal godfather system in the Niger Delta by removing corrupt personnel and terminating the funding means for this relationship (amnesty payments and security contracts to demobilised ex-militants) has failed in the short term. While the rise of the NDA is directly linked to this, it was not a guaranteed outcome of the government’s planned “post-amnesty” policy at this point. Many former militants seem to be content keeping their heads low for the time being.

It was apparent that Niger Delta armed groups, lavishly supplied with weapons and ammunition by political parties in the run-up to the 2015 national elections, were fighting amongst each other. New groups and alliances were emerging, and continue to emerge, as the former militants’ networks were weakened through the absence of patronage and funds by the previous government of President Goodluck Jonathan. This development began to take shape in mid-2015, as privileges and contracts were gradually removed by the government. By January 2016 new groups, like the CML or the re-invigorated Niger Delta People Democratic Front (NDPDF) became noticeably more public, vying for influence and public attention. Threats of resumption of violence abounded whenever the topic of the reduction or termination of the Presidential Amnesty Programme was raised by the government.

The emergence of the NDA can be seen in this context and is likely linked to the collapse of Tompolo’s influence in his home area of Warri South West LGA in Delta state. Tompolo had been one of the major profiteers of the amnesty payments and inflated security contracts with the Nigerian Maritime Safety Agency (NIMASA). In January 2016, the Nigerian government made an example of NIMASA’s senior officials and their sponsor, indicting them to appear before court on no less than 40 counts of fraud.

Whether the NDA are Tompolo’s former foot soldiers, clients, constituents or rivals that were kept low through his “security” activities in Delta state is uncertain, but the constant reference to Tompolo and Gbaramatu Kingdom (a traditional chieftaincy) sufficiently defines the geographic location to make the NDA a local phenomenon – for the time being. The overwhelming number of attacks carried out in the Warri South West LGA (and the neighbouring Burutu LGA) also supports this assumption. Nigerian intelligence and military, encouraged by statements of former militants like Boyloaf, seem convinced that Tompolo, who is a fugitive since the court order was issued against him on 12 January 2016, is involved in NDA activities. While this is possible, it is also highly unlikely since he would have nothing to gain from such an involvement in his current predicament.

A circumscribed geographic location allows a rough estimate of the personnel strength of the NDA. Based on historical patterns of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) insurgency (2006-9) and camp sizes in the area, a core strength of not more than 100 fighters, most likely of Ijaw extraction, would seem likely. The NDA assign them to “Strike Teams” although this, like during the MEND insurgency, seems to be a largely propagandistic element. The NDA also claim “mixed ethnicity,” being at least Ijaw and Itsekiri. This is, at least in theory, plausible, since Warri lies at the crossroads between the Ijaw, Itsekiri (both reside in the coastal area) and Urhobo communities. Organisations of all three ethnic groups have vigorously denounced the NDA.

The NDA have an active communication strategy that appears to work well. For the time being, they are shaping the information battlefield with the Nigerian government falling behind. The NDA utilise two primary outlets: their website and a Twitter account. They also send emails to an email distribution list, but it would seem to be a backup. The NDA fashion themselves very much like a MEND 2.0. Their spokesman is “Brigadier-General” Mudoch Agbinibo (recently promoted from the rank of “Colonel”), a jibe against the Nigerian military, whose Director of Information is Brigadier-General Rabe Abubakar. Whereas MEND revelled in reports of successes against the Nigerian military, however, the NDA have gone to great lengths to stress that they have not caused a single military casualty so far (even if a number of attacks on military outposts have been blamed on them). They prefer to deride the security services for their inability to prevent attacks that are being carried out under their noses.

The NDA strategy benefits from the group’s relative smallness. Unlike MEND, the NDA do not rely on compromises (MEND fragmented early in its life due to a disagreement over payments of ransom money from the Wilbros kidnappings in 2006), have a unified command, a target-rich but small operating environment, as well as trained personnel – better trained than MEND ever had thanks to the amnesty programme, and something the NDA credit themselves with. The NDA are active in only two localities: Warri South West LGA (including the fringes of the adjacent Burutu LGA) and the Brass Nembe LGA. Their actions are typically seen to follow government action, more recently preceded by more or less specific threats and usually followed up with multiple attacks against oil and gas targets. Reactions by traditional chiefs in Gbaramatu Kingdom suggest that there is no consultative process or even tacit agreement; the NDA rely solely on themselves. This has allowed the NDA to escalate the conflict to an intensity rarely achieved during the MEND insurgency. This aggressive strategy may cut both ways in the way of classic insurgency theory. It can alienate the population it is meant to inspire and subsequently deny a larger popular following for the NDA, possibly leading to the creation of competing militant groups. It can also generate a bumbling military backlash against (most likely) uninvolved communities and leaders thus generating a popular following for the NDA by driving disgruntled individuals into their arms – or those of their more violence-prone rivals.

The risk of the NDA losing “control” over the insurgency is very real and their first competitors and rivals for public attention (and a seat at the negotiating table) have manifested themselves in late May and early June 2016. Some may also have simply spotted an opportunity for self-enrichment through extortion in a failing security environment. The elitist and purposeful strategy employed by the NDA clearly does not appeal to all. In late May and early June 2016 the Bayelsa-based Joint Niger Delta Liberation Front (JNDLF), for example, issued threats against the military in a more provocative manner (including pronouncing a no-fly zone for the Nigerian Air Force); unknown gunmen attacked an army houseboat near Warri on 1 June, killing as many as 20 persons in the process, and the Monty Pythonesque-named New Delta Suicide Squad (NDSS) went public with a bid to extort private oil and gas facility operators or face acts of sabotage.

The NDA have emphatically denied being involved in any of these activities or organisations. This denial is likely to be credible, since the NDA would view such activities as a distraction from their operations and agenda and a dilution of their own role in Niger Delta affairs. They are also likely acutely aware that the killing of soldiers in May 2009 was used as an excuse by the Nigerian government to launch a massive military operation in Gbaramatu Kingdom that effectively ended the MEND threat in Delta state.

Nigerian Government Strategy

The government’s strategy to quell the resurgent militancy in the Niger Delta, and the NDA in particular, seems two-pronged following the failure of the strategy aimed solely at dismantling the godfather networks and marginalising corrupt and criminal elements that had become pre-eminent in the Niger Delta under the previous presidency.

While president Muhammadu Buhari declared on 13 April that he would crush the Niger Delta insurgency like he crushed (of sorts) Boko Haram in the North-East, he is sufficiently alert to reality to understand that this is a necessary threat that needs to be issued, but military action alone will most likely not be the main thrust of his counter-insurgency strategy. At least not initially, although a concentration of forces in the Warri area is already becoming palpable. The Nigerian Navy shifted its focus from the suppression of piracy to counter-insurgency, re-deploying its vessels assigned to Operation ‘Tsare Teku to the area. Like the government and the rest of the security forces, the Navy had been caught on the back foot by the sudden intensity of the NDA’s pipeline bombing campaign. Intelligence on the group remains sketchy and a severe constraint on focused counterinsurgency operations.

As oil production plummeted in May 2016 as a result of the pipeline attacks, Buhari quickly reversed his previous policy of marginalising former militant leaders. Although some former militants had even joined the president’s camp, the majority were agitating against the planned reduction and discontinuation of the amnesty programme; it seemed to come down to a pecuniary issue for them. As such, it was comparatively easy for Buhari to do an about face at the end of May and hold out the prospect of a “re-engineered” amnesty to those ex-militants (with further prospects of enrichment for them). While this has cost his anti-corruption drive some credibility, it was a pragmatic solution for containing the NDA threat and preventing it from spilling over into the areas controlled by those former militants. The “rehabilitated” ex-militants also dutifully obliged by denouncing the NDA. The success of the overall strategy now very much hinges on the degree of influence of those ex-militants and stakeholders that Buhari can marshal for his ends. There is also a time constraint. Buhari’s sworn political enemies are currently in disarray. He therefore needs to succeed before his political detractors can rally local support to sabotage the process. He also needs to succeed before NDA attacks further drive down oil production and government revenues, thus impacting on the Nigerian state’s ability to deliver basic services to its population.

Because diplomacy without force is like music without instruments, Buhari also made it clear that if all else fails he will use force. It should be remembered that in spite of all criticism (and the very real limitations) of the Nigerian military, it was the military offensive against the militant camps in Gbaramatu Kingdom in May/June 2009 that forced Tompolo, then the most powerful “General” of MEND, to the negotiating table and that cleared the way for the relative success of the Presidential Amnesty Programme by the late President Yar Adua. The cost to the local population was high – more than 1,000 persons were believed to have been killed and 30,000 were made temporarily homeless. The message Buhari could be sending to the communities, as warships and ground attack helicopters assemble in the area, is: give up the NDA or risk a repeat performance of 2009.

Dirk Steffen is a Commander (senior grade) in the German Naval Reserve with 12 years of active service between 1988 and 2000. He took part in the African Partnership Station exercises OBANGAME EXPRESS 2014, 2015 and 2016 at sea and ashore for the boarding-team training and as a Liaison Naval Officer on the exercise staff. He is normally Director Maritime Security at Risk Intelligence (Denmark) when not on loan to the German Navy. He has been covering the Gulf of Guinea as a consultant and analyst since 2004. The opinions expressed in this article are his alone, and do not represent those of any German military or governmental institutions.

Featured Image: Fighters of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) prepare to head off for an operation against the Nigerian army in the Niger Delta on September 17, 2008. MEND declared full-scale ‘oil war’ against the Nigerian authorities in response to attacks by the Nigerian military launched against the militants. “Our target is to crumble the oil installations in order to force the government to a round table to solve the problem once and for all”, said Boyloaf, leader of the militants (now, in 2016, an ally of the government). AFP PHOTO/PIUS UTOMI EKPEI.