The 2010 British Strategic Security and Defence Review (SDSR) begun with an unambiguous statement of intent; ‘Our country has always had global responsibilities and global ambitions. We have a proud history of standing up for the values we believe in and we should have no less ambition for our country in the decades to come’. It then goes on to outline how this might be achieved. Britain must be ‘more thoughtful, more strategic and more coordinated in the way we advance our interests and protect our national security’[1]. But since 2010 the record has not reflected these aims. If anything, it seems the British government is becoming less and less clear about what it wishes to achieve in the international arena in service of British national interests. Written in the light of recent adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan, the document admits that Britain’s ‘Armed Forces – admired across the world – have been overstretched, deployed too often without appropriate planning, with the wrong equipment, in the wrong numbers and without a clear strategy. In the past, underfunded spending pledges created a fundamental mismatch between aspiration and resources’[2]. The murderous march of Islamic State (previously ISIS) through Iraq, the ever present and resurgent Taliban threat in Afghanistan and the declining civil order in Libya all demonstrate the damaging consequences of ill-conceived and ill-planned military intervention. Professionalism, success and sacrifice at the tactical level have not translated into success at the strategic level, largely due to the simple fact there has been no overarching strategic direction, set at the political level, guiding operational and tactical planning. The consequences of Britain’s twenty-first century interventionist wars are yet to be fully felt, but they are unlikely to lead to the stability and peace in the Middle East, and security at home, that was envisaged.

The key reason for defeat in these campaigns was a failure of British policymakers to fully appreciate the military, political and cultural dimensions of the regions and conflicts in which they were getting involved. This inevitably led to an inability to develop a singular strategic aim and appropriately plan for contingent outcomes, leading to confusion around how to respond both politically or militarily to evolving contexts. Ultimately, this bewilderment was an predictable consequence of fighting the wrong conflicts, conflicts that did not directly serve British or indeed, global interests, or in fighting them in the wrong way (as in Afghanistan where limited intervention led to strategic creep – ‘nation building’ – and a blurring of aims and means, and in Libya where short term kinetic intervention has led to long term instability). For these reasons, Britain and her allies could never secure long-term victory. If London did not set criteria for victory, how could it possibly achieve it? As the British naval thinker Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond once cautioned in his 1946 study ‘Statesmen and Seapower’; ‘If the statesman misinterprets the nature of national defence or the ultimate object of a war, or fails to make the necessary preparations; if, in war, he misdirects the strategy employed for the attainment of the object; the results will be far more injurious than those of errors in minor strategy or tactics: for they are more far-reaching’[3]. These words have acquired fresh resonance.

The campaign in Libya and the lobbying for intervention in Syria still demonstrate that the incumbent UK government, despite the promises made in the SDSR, does not understand what national security means and how the application of force might serve to uphold it. If the UK government seriously decides that it is in the UK’s national interests to involve itself in wars such as have been fought or proposed in recent years, then it must first write a coherent foreign policy to justify this approach, then develop a defence strategy reflecting this approach, providing ample financial and military resources in order to deliver it. If however, it considers such increases in defence spending as impracticable, and prolonged ground wars as impracticable, then a sober refocusing and apposite downsizing of our national ambitions and strategy is required. Based on the recent record the latter is perhaps more palatable; the more a nation engages in conflicts that they do not understand, both in the long and short terms, the more likely they are to lose credibility in the eyes of their potential enemies, emboldening and perhaps multiplying them. Military capability must match the politicians rhetoric. It is in this, that the soft and hard-power capabilities afforded by flexible and numerous maritime forces present themselves. For a nation such as Britain, who wishes to retain global influence but contain defence spending, a well resourced maritime force can offer a cheaper, more effective, less invasive and more flexible means of meeting the basic security requirements demanded of an Western government[4].

Where the SDSR does start to talk sense is in its clear contention that British ‘national security depends on our economic security and vice versa’. Stemming from her island status, Britain’s economic health is dependent on the sea. 90 – 95% of British imports and exports are dependent on the sea and UK based shipping contributes £10bn to GDP and £3bn in tax revenues and after tourism and finance, is the third largest service sector industry in Britain. In 2011 the Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr) forecasted that globalisation is simply increasing British dependence on maritime trade. After adjustments for inflation, seaborne imports are projected to grow 287% over the next two decades, and exports delivered increasing by 119%. The value of British imports in 2010 stood at £345bn and is expected to reach £1.95tn by 2030. In the same twenty-year period export values are expected to rise from £233bn to £1.63tn[5].The SDSR however fails to grasp such facts. A maritime focus for foreign and defence planning is critical. It has been through shrewd exploitation of the maritime realm for global influence, trade, diplomacy and war fighting, that Britain had forged and refined successful foreign and defence policy postures framed by her seapower status. But such is modern Britain’s general lack of understanding of the role of the Royal & Merchant navies in shaping British history, that the efficacy of this foreign policy posture is poorly understood. Thus it is unsurprising that Britain is now struggling to develop a coherent national strategy that serves her interests and not the whims of vote-winning, short-termism.

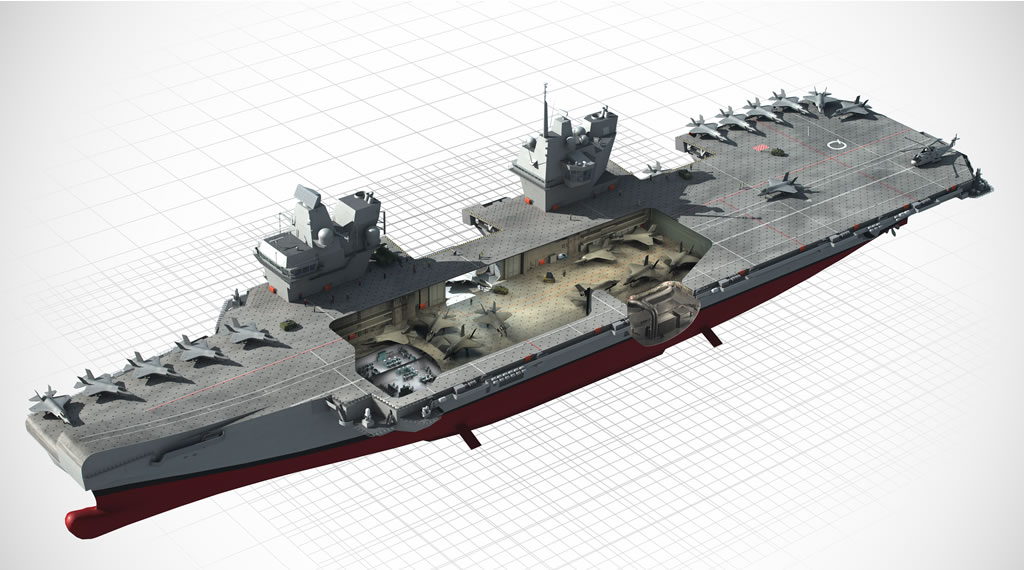

As a result of the SDSR of 2010, the UK armed forces are getting smaller, meaning Britain must be more discriminating about its utilization of hard power. To achieve this aim, Britain must develop a coherent and focused national strategy, structured around its reliance on the sea. A strong Royal Navy can deliver defence of trade, conventional deterrence, counter-narcotics operations, counter-piracy, upholding the rule of law at sea, diplomacy (‘showing the flag’ missions), global air-power projection, support of operations ashore[7], and of course maintaining the at-sea nuclear deterrent. There is great utility in such a force that can deliver all these things at proportionally little cost.

However, if Britain continues to fail to appreciate its historic relationship with the sea and how it has been utilised, in war and peace, in the defence of her interests, it will remain ignorant to the potentialities of the maritime realm in the modern day. It is my contention, that if exploitation of the sea for influence, prosperity, security, and military effectiveness, continues to be sidelined as a core strategic function, by continued under-investment in maritime forces, then Britain’s credibility as a global power will atrophy. Herbert Richmond explained that a State’s ability to deliver decisive military action rests on that state’s strength, whether it has appropriate and well-maintained arms to pursue the objective and ‘whether they have been kept sharp or blunted by ill-considered policy, surrender of territory, of interests, or of rights concerning their use’[8]. Britain’s ‘ill-considered policy’ of the past decade has arisen from a misplaced sense of purpose and strength and it has repeatedly ignored the sources of its power and thus failed to deliver lucid thinking on national strategy. The SDSR failed to interpret British interests, and the threats to them, in the longer term. In putting terrorism as a core focus of British defence efforts, the authors have shown a collective failure to understand that terror does not present a long term menace to the prosperity and security at home that Britons have come to expect. Therefore terrorism should not be a phenomenon that shapes a nation’s foreign and defence policy posture. A nation’s armed forces should remain flexible to respond to and prevent acts of terrorism, but should not be focused on them.

To highlight terrorism as a top priority of British defence planning suggests that Britain, despite the lofty rhetoric of the SDSR, is still doing defence, security and indeed strategy, wrong. Britain’s recent failure to fight wars in support of clear foreign policy goals would appear to draw this out. For instance, its reliance on the purported efficacy of foreign aid is perplexing, when in reality the value of its use is far from certain. The money would be better spent on a maritime force capable of delivering tangible security, tried and tested over hundred of years. These views are shared by Dr David Betz of King’s College London, who in a recent unequivocal post on the War Studies Department Blog argued that ‘For three hundred years… a cornerstone of British policy has been the maintenance of a very good, at times world pre-eminent, navy–even through the 20th century during which its relative power progressively diminished… On current trajectory, presently we shall have a not very good navy at all with serious gaps in capability and depth’[9]. Betz’s final point is perhaps the neatest exposition of what this writer believes needs to happen; ‘If it were up to me every damned penny currently earmarked for overseas aid would be redirected to the Royal Navy permanently. There’s nothing better for lifting poverty than trade’[10].

Britain is a de facto seapower. But its failure to appreciate this is the greatest threat to its long-term security. The scrapping of Nimrod Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), the Harrier fleet and the current aircraft carriers before replacements were in commission and the delivery of only 6 Type-45 Destroyers instead of the proposed 12, all show a lack of appreciation by government officials of what a flexible naval capability requires. Such a high proportion of the future fleet will be required to protect the new carriers that it will be unbalanced and hard choices will have to be made about whether other critical routine operations can be maintained. Either that or more time will be spent at sea with implications for moral (another focus of the SDSR), retention and maintenance. When reading the SDSR document, it fails to account for the unpredictability of the world and the lessons of history. For instance, it stated ‘in the short term, there are few circumstances we can envisage where the ability to deploy airpower from the sea will be essential. That is why we have, reluctantly, taken the decision to retire the Harrier aircraft, which has served our country so well’[11]. Within the succeeding 4 years, air strikes were launched against Libya from bases in the UK and Italy – even the Italians flew their missions from the Giuseppe Garibaldi – at exorbitant cost and prominent officials were lobbying for a similar intervention in Syria. Only in the last fortnight America has begun launching airstrikes against IS in Iraq. The UK may provide similar support but only enabled by the fortuitous location of her base in Cyprus. Future events will undoubtedly once again throw the gap in Britain’s maritime capabilities into sharp relief. But until this elusive moment of clarity, London must begin to refocus foreign policy aims to directly service the nations interests and do this by beginning to acknowledge the nations historic and tested credentials as an effective seapower.

The world is becoming more fractious, unstable and to boot more nations with bright economic futures – some with values divergent from those of the West – are pursuing naval programmes. It is not good for a nation such as Britain, so dependent on the security of the world’s seas, to realign its defence focus to terrorism (and the sources of it), put so much faith in dubious international aid payments whilst neglecting its duty to upholding the security of the world’s oceans. Despite the dreadful consequences of individual terrorist acts, they will regrettably never be eliminated and the threat they pose to the wider security of Britain remains disputed. The defeat of terrorism and the instability that feeds it, through foreign aid and armed intervention, is an illusory aim and the pursuit of it will inevitably continue to lead to future embroilment in costly and ineffectual foreign adventures that do not safeguard Britain’s interests, or its security. Instead, the upcoming SDSR of 2015 must refine Britain’s global ambitions and be selfishly realistic in what it can and cannot achieve vis-à-vis defence and security, instead of pursuing nebulous and discredited aims such as the defeat of terrorism. This post, in addition to the last 400 years of British history, has demonstrated that the UK should pay proportionally more attention to events in the maritime realm and must invest to maintain a strong, flexible maritime armed force (this means numbers not just technologically advanced platforms). The Royal Navy has proven through history to be adaptable, delivering security, prosperity and influence through business-as-usual global operations; able to respond to a broad array of contingencies with finesse or force. London must re-engage with the history of the Service that facilitated its rise to world power status and focus not just on what its armed forces can deliver in war but also what they can deliver in peace. Only in doing this will it truly re-learn the importance of the Royal Navy and the utility of seapower.

Simon Williams received a BA Hons in Contemporary History from the University of Leicester in 2008. In early 2011 he was awarded an MA in War Studies from King’s College London. His postgraduate dissertation was entitled The Second Boer War 1899-1902: A Triumph of British Sea Power. He continues to write on naval history and strategy and in 2012 he hosted the Navy is the Nation Conference, in Portsmouth, UK. The aim of this event was to explore the impact of the Royal Navy on British culture and national identity. His is organising a second event entitled Statesmen and Seapower, being held in partnership with the National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth on 17 & 18 April 2015.

[1] ‘Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review’ https://www.direct.gov.uk/prod_consum_dg/groups/dg_digitalassets/@dg/@en/documents/digitalasset/dg_191634.pdf accessed 13/08/14

[2] ‘Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review’ https://www.direct.gov.uk/prod_consum_dg/groups/dg_digitalassets/@dg/@en/documents/digitalasset/dg_191634.pdf accessed 13/08/14

[3] Richmond, H. ‘Statesmen and Seapower’ (OUP, 1947) p.vii

[4] Discussion of the cost-effectiveness of warships was discussed in an earlier post.for this blog https://cimsec.org/learning-from-history-british-global-trade-and-the-royal-navy/7145

[5] Osborne, A. (2011) ‘Britain’s reliance on sea trade ‘set to soar’’ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/transport/8696607/Britains-reliance-on-sea-trade-set-to-soar.html accessed on 19/08/13

[7] It must however be stressed that a strong tri-service arrangement is a pre-requisite for effectiveness ashore and must be nurtured in tandem.

[8] Richmond, H. ‘Statesmen and Seapower’ (OUP, 1947) pv.iii

[9] D. Betz, ‘Britain’s Naval Moment’ http://kingsofwar.org.uk accessed 13/08/14

[10] D. Betz, ‘Britain’s Naval Moment’ http://kingsofwar.org.uk accessed 13/08/14

[11] ‘Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review’ https://www.direct.gov.uk/prod_consum_dg/groups/dg_digitalassets/@dg/@en/documents/digitalasset/dg_191634.pdf accessed 13/08/14