By Matthew Connors

The campaign against Nazi Germany is often characterized as a land battle, but Hitler also lost the war by losing the sea. The former army corporal never truly grasped the importance of sea power and did not appropriately invest in Germany’s navy. Despite this, the Kriegsmarine nearly broke Britain through its use of aggressive surface action groups (SAGs) and irregular commerce raiders. The Kriegsmarine entered a war it was ill-suited for, well before it was prepared to fight, but by employing a form of maritime compound warfare it nearly disrupted Allied sea control which would have starved Britain and the Soviet Union of seaborne supply. Germany’s near victory demonstrates the potential of compound war at sea.

Qualifying Germany’s Naval Campaign as Compound War

In compound war a commander makes use of irregular units operating out of secure bases and augments them with the threat of conventional forces that can also take on irregular operational patterns.1 These irregular operations can force an opponent to disperse forces across a broad space to protect vital points and supply lines from irregular raiders and guerillas. This works in tandem with the presence of a regular conventional force which requires an adversary to also maintain a sizeable concentration of units to potentially counter a large-scale offensive, similar to a fleet-in-being.

This dilemma is precisely what makes it difficult to counter a compound campaign. On land, successful compound campaigns have been waged by Washington, Wellington, and Ho Chi Minh. At sea, compound war is less common, where fleets usually contest control of the sea through fleet combat actions dominated by regular units, or raid with irregulars and dispersed units. Yet, by employing a mix of both regular combatants and irregular raiders, the Kriegsmarine essentially waged compound war from 1939 to 1942.

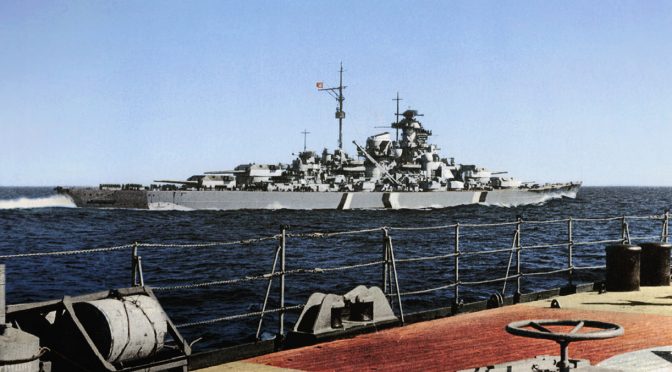

Broadly defined, German naval forces can be split into regular and irregular combatants.2 Regular surface combatants could engage the enemy battle line or decimate lightly defended convoys. Germany’s surface striking forces mainly consisted of cruisers and battleships. These warships sowed chaos among the British Admiralty and forced the Royal Navy to cover multiple convoys and large areas while hunting small groups of German combatants.3 The presence of one pocket battleship or heavy cruiser in the Atlantic generated the need for convoys to have major surface ship escorts lest they fall prey to the big guns of a German warship. The high speeds and potent offensive capabilities of the German surface fleet could induce the Allies to scatter lightly protected convoys, which limited the damage done by heavy German combatants, but exposed them to the predations of German irregulars, submarines, and aircraft. The best example of this dual threat at work was the case of Convoy PQ17, an Arctic convoy traveling to the Soviet Union in 1942. The threat of a task force led by the German battleship Tirpitz forced the dispersion of the convoy’s ships and caused their subsequent destruction in detail by submarines and the Luftwaffe.4

Compound war at sea enhanced the psychological threats posed by German heavy surface ships and the German irregulars. By acting aggressively, the Kriegsmarine forced the British to deploy every available ship in their fleet to hunt for a handful of German surface ships.5 The Germans also conducted an extensive mining campaign that sought to deprive the British of their own shipping through destruction and neutral shipping through deterrence.6 The strain of constant operations and a shrinking merchant fleet was designed to cripple the Royal Navy and the commerce it protected, leaving the British Isles exposed and cut off.

The Regular Naval Threat: Surface Forces

In 1939 and 1940, aggressive commerce raiding in the Atlantic and Indian oceans by German heavy ships caused panic in Britain. The deployment of the Scheer, a pocket battleship, caused the Royal Navy to dispatch an aircraft carrier and six cruisers.7 A subsequent cruise by the battleships Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau sank 115,000 tons of shipping in two months, forced the deployment of the British home fleet, and managed to delay convoy sailings until battleship escorts could be found.8 In late 1941, plans were drafted for the operation of a surface action group out of Norway coupled with a commerce raiding deployment launched out of France. The surface action group would have drawn the British home fleet away while the raiders sowed chaos on Allied shipping.9 These operational plans and deployments typified the German approach and were designed to spread confusion and disruption through aggressive action.

German heavy ship operations featured regular units acting in irregular ways. While any individual platform could engage a rival, they did not have enough to risk themselves in regular combat. Therefore, the Kriegsmarine sought to fight on favorable terms against lightly guarded convoys. When the German forces found themselves outmatched by convoy escorts, they would still engage, but they would often avoid wholly committing themselves to fighting a well-guarded convoy.

Despite their irregular behavior, the German surface fleet’s potential as a regular naval threat remained potent, demonstrating the power of a fleet-in-being. The retention of a German fleet also provided the British with a strategic situation in line with the compound war concept. The continued existence of German heavy units required the Royal Navy to retain a home fleet sufficient to crush a concentrated German excursion while forcing it to also protect distant supply lines against commerce raiders, even after SAG deployments effectively ended in 1942. Even as the German surface fleet was either bottled up or sunk, it remained a real threat and a constant source of British dread. While auxiliary cruisers and submarines could be dealt with by destroyers and aircraft, German battleships and cruisers demanded strong attention from the Royal Navy.

At one point early in the war the Commander-in- Chief of the Kriegsmarine, Admiral Erich Raeder, asserted that the loss of a major German capital ship was not of major significance, especially if lost as a result of “bold action.”10 Audacity, aggression, and frequent operation on the part of the capital ships was part of cultivating their threat potential and stressing the Royal Navy’s resources and leadership. Their mere existence as a fleet in being posed a threat and required the British to divert resources from anti-submarine warfare operations and convoy escort duties. German SAG deployment arguably stalled Allied convoy departures and reduced British imports far more effectively than the grinding destruction of U-boat warfare.11 But after the battleship Bismarck was lost on a raiding mission in the Atlantic the utility of these heavy units shrank as Hitler became concerned about their potential loss and was unwilling to further risk them in combat.

The Irregular Subsurface Threat: Submarines

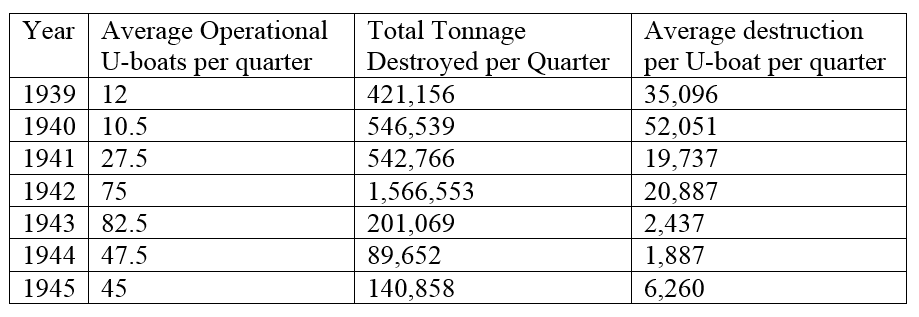

Admiral Karl Donitz, the head of the U-boat wing and eventual commander of the German Navy during WWII, conceived of a mathematical war against the British. The war of tonnage was designed to sink first British and French and later American merchant shipping quicker than it could be built. The resulting reduction in carrying capacity and goods would cripple Allied industry and force an armistice.12

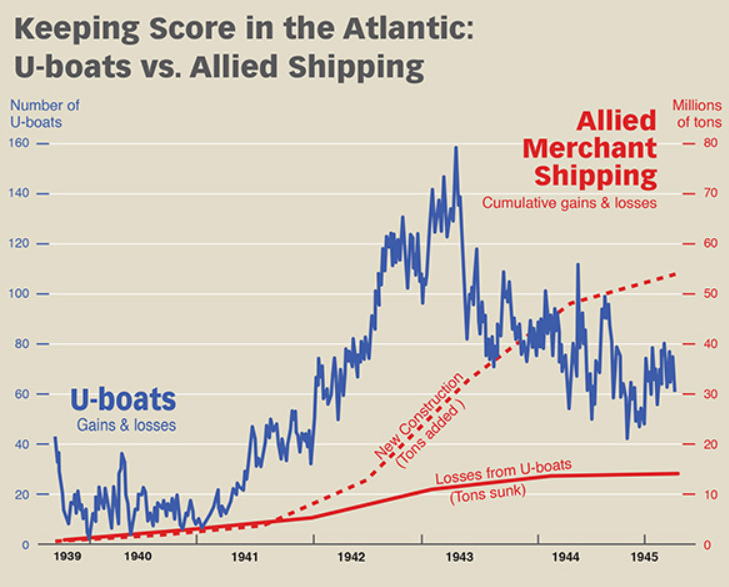

The irregular component of the Kriegsmarine’s maritime compound warfare was executed by irregular surface and subsurface commerce raiders. These small, cheap platforms were designed to be stealthy enough to bypass the Allied naval blockade and cruise against allied shipping. Despite some false starts and early restrictions, unrestricted submarine warfare, once joined, proved theoretically possible. While British and American shipbuilding and convoy systems eventually overwhelmed the U-boat Arm’s destructive capacity, it wasn’t until 1943 that production outstripped destruction. 1943 also witnessed a sharp decrease in the U-boat’s efficacy as Allied convoy tactics, air-ASW, and the breaking of the Enigma codes proved increasingly effective at neutralizing U-boat attacks on convoys.13 The entry of the U.S. into the war and the increasing tactical effectiveness of ASW saved the Allies in the Atlantic.

However, had German force structure and strategy been built around commerce destruction by the time war broke out in 1939, it may have succeeded in breaking Britain. German unrestricted submarine warfare proved ineffective, not because of tactical failings or strategic blunders by Admirals Raeder and Donitz, but because German industry, technology, and strategic cooperation proved inadequate. The incredibly small size of the U-boat Arm at the start of the war, only a sixth of the estimated force necessary to break the British, would grow as production gradually ramped up, but losses exceeded production until July of 1940. The force did not reach the necessary 300 boats until April of 1942, but only after the U.S. had entered the war and after tactical ASW was trending in favor of the allies.14

A rough estimate of the required tonnage destruction rate that could force British capitulation was 1,800,000 tons per quarter.15 Assuming a similar destruction rate, had the 82.5 deployed U-boats per quarter attained in 1944 been reflected in the average 1940 quarter, total tonnage destroyed could have amounted to 4,294,207 tons destroyed per quarter.16 Such a shock would have starved the British war machine and people. However, the German U-boat force of the first years of the war was, like the surface force, insufficient for the requirements of the German campaign.

The famed wolfpack was even temporarily abandoned after it became apparent that there were not enough U-boats to actively execute the tactic.17 As Allied ASW efforts improved, convoys became capable of inflicting heavy damage on their attackers and U-boats became increasingly subject to destruction en-route to the hunt. In 1943 the mid-Atlantic “air gap” was closed by escort carriers and Allied ASW units improved in both quantity and quality, reducing the U-boat’s destructive potential.18 The U-boat force peaked in early 1943, and production spiked to 79 new U-boats in 1944, but the window had passed.19

Organizationally, German U-boats were kept under relatively centralized control. Their limited ability to detect convoys and coordinate with other U-boats necessitated their direct operational command by Donitz and the U-boat branch in Wilhelmshaven.20 Wilhelmshaven would act as a central processing hub for data, either from submarines, aircraft, spies, or auxiliary cruisers and then concentrate a number of U-boats in the vicinity of a convoy. This concentration of boats would then attack at night on the surface where they had a speed advantage over allied merchantmen. However, the Naval Staff would also give orders directly to commanders, which complicated the command and control process.21 Tight control and cueing was necessary to ensure U-boats made contact with as many enemy ships as possible so as to maximize their statistical impact. This control, encrypted by the Enigma and Triton cyphers, was subject to Allied penetration. When this occurred, the Allies started avoiding submarines, reducing their efficacy.

One of the most crippling deficiencies of the German strategic approach resulted from the schizophrenic nature of Nazi high command. Historian Donald Steury assessed inter-service competition between the Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine as a major hinderance to joint operations against Allied shipping.22 Donitz himself points to Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering’s staunch prohibition of an independent maritime airwing and bogarting of resources as having both limited the operational capabilities of the fleet in a broad sense and the size of the U-boat arm in particular.23 This resulted in minimal aerial scouting which frustrated Donitz’s early efforts to coordinate wolfpack operations and interdict Allied convoys.24

The Kriegsmarine had a sound strategic concept, but an inadequate force that lacked joint support. Despite their fearsome reputation, the U-boat was never properly employed to its full potential, and when coupled with Allied efforts this meant the effective defeat of Germany at sea.

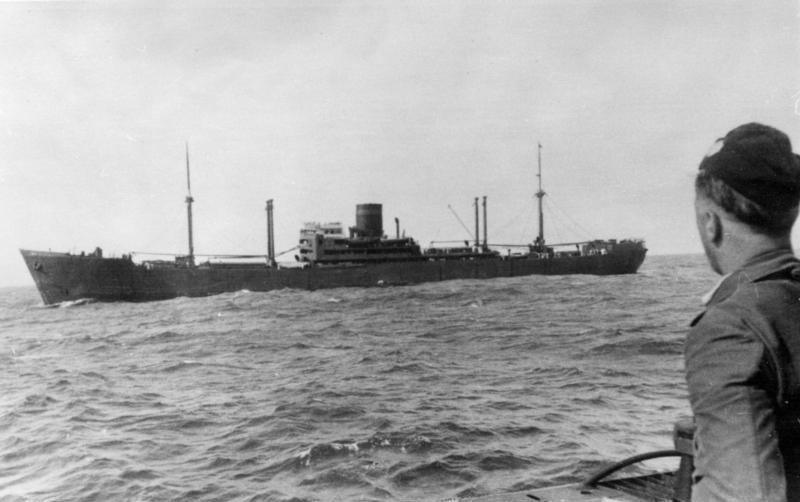

The Irregular Surface Threat: Auxiliary Cruisers

Auxiliary cruisers were launched to raid allied commerce but carried out a variety of support operations. These ships were converted merchantmen, altered to carry heavy armament and equipped with reconfigurable superstructures. Designed as stealth commerce raiders, there were only a few of these ships but they had an outsized impact. HSK-5, the Pinguin, sank or captured 154,619 tons of allied shipping, a total tonnage on par with some of the U-boat wing’s top performers. By comparison the U-boats sank approximately 11,023 tons per U-boat commissioned.26 Comparatively, the auxiliary cruisers did quite well, between the nine ships deployed from 1940-1943: 844,321 tons of allied shipping were destroyed, or 94,035 tons per auxiliary cruiser.27 Their effectiveness demonstrates the potential of such a vessel and role.

These irregular platforms had a mix of advantages and disadvantages. They were always exposed and subject to possible destruction by a curious surface combatant, the conversion process from merchant to warship was lengthy, and escaping into the Atlantic or Arctic oceans exposed them to detection and destruction by British forces. However, their high average destruction rate is reflective of their inherent capabilities. As surface vessels, they could make high speeds, could remain underway and operational for extremely long periods of time (622 days in the case of the Atlantis), and even could operate light aircraft.28 The ability to operate aircraft afforded them a degree of independence not found in the U-boats, and where the U-boat was heavily dependent on outside cueing for finding targets rather than its organic search capability. Because auxiliary cruisers could operate aircraft they could expand their personal search horizons, far superior to that of the relatively low conning tower of a submarine or its sonar.

Furthermore, the expanded crew size and cargo capacity allowed these stealth platforms to execute covert auxiliary tasks. Auxiliary cruisers mined Allied harbors all over the world, supported U-boats, and captured or destroyed Allied shipping. As surface ships, their interactions with enemy merchantmen allowed them to extend operations by refueling and resupplying from the prizes.29 These ships remained operational in the Atlantic slightly longer than the regular German fleet. However, like regular surface raiders, these platforms became increasingly difficult to deploy and the last attempt at a breakout failed in February of 1943.30 The auxiliary cruiser was an innovative and potent tool undercut by a lack of investment and the later conservativism of the German fleet. Much like the submarine, the auxiliary cruiser was doomed by a profound lack of investment in the German fleet and Hitler’s naval hesitance.

German Naval Force Structure: Idealism at the Cost of Realism

Admiral Raeder, who led the Kriegsmarine from 1928 to 1943, was mostly responsible for the reconstruction of the German fleet in the interwar period.31 After Hitler seized power naval building accelerated. Light cruisers, heavy cruisers, battlecruisers, and two battleships were constructed.32 However, Raeder’s Plan Z shipbuilding program was designed to build a fleet optimized for a compound campaign against the British. The Plan Z fleet centered on a robust home fleet, several striking forces, and commerce raiders. The home fleet would be strong enough to challenge the British home fleet, thus demanding the retention of the bulk of the Royal Navy’s capital ships in home waters, while the striking forces and commerce raiders starved the British by crushing convoys and sinking lone merchants. However, Plan Z required a longer lead time than a competing fleet design plan which would have consisted of a large submarine branch and multiple pocket battleships.

Operating under the assumption that hostilities would not commence until the mid-1940s, the Germans selected Plan Z. However, the decision to launch WWII by invading Poland in early 1939 took the naval staff almost entirely by surprise. The invasion launched the Kriegsmarine into war prematurely and well before the Plan Z buildup could be completed.33

Losses and an increasing hesitancy on the part of Hitler to risk capital ships eventually reduced the potency of the German surface force and increased the Kriegsmarine’s reliance on submarines.34 However, the German Navy started the war with an insufficient submarine fleet of only 57 boats, when an estimated 300 were required for war with Britain.35 Hitler’s hesitance and ignorance of the sea kept the Kriegsmarine weak, when he lost his nerve in 1942, he constrained his surface navy which then became mostly irrelevant, leaving his inadequate submarine force to carry on what was becoming a losing naval campaign.

Conclusion

Early British deficiencies gave the Kriegsmarine a chance at victory. British ASDIC (active sonar) often performed poorly; the convoy system was initially resisted, and British shipbuilding was not able to catch up to the rate of destruction until 1943.36 The cancellation of the regular surface campaign in the Atlantic in late 1941 was followed by an uptick in overall British imports, despite the increase in U-boat sinkings in 1942.37 Raeder and Donitz had a winning strategic concept but an inadequate force. While compound threats are typically potent, the Kriegsmarine was unable to execute a consistent, effective campaign. As ‘Fortress Europe’ began to crumble, the effectiveness of the German maritime campaign plummeted further still. Ultimately, Hitler’s strategic failings and the small size of the German fleet at the beginning of the war caused the Kriegsmarine’s failure.

The Kriegsmarine’s shortcomings were matched with Allied successes. Cracking Enigma, the reimplementation of the convoy system, the implementation of air-based ASW, and general improvements in ASW operations saved the British merchant from the U-boat, while brave men in steel ships defeated the big guns of Hitler’s surface fleet. A future war at sea against a compound threat will require much of the same: superb code breakers, clever screen commanders, effective tactics, and brave Sailors willing to grapple with any threat.

Lieutenant Matthew Conners is a 2012 graduate of the Naval Academy and a Surface Warfare Officer. He has served in USS Hopper (DDG 70) as Repair Officer and USS Chung Hoon (DDG 93) as the Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer. He is also the recipient of the Naval Postgraduate School’s 2018 Liskin Award for excellence in National Security Studies. He graduated from the Naval Postgraduate school in 2018 with a Master of Arts in Security Studies. He is stationed in San Diego at the Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center.

References

[1] Thomas Huber, Compound Warfare; That Fatal Knot, (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Press, 2002) https://usacac.army.mil/cac2/cgsc/carl/download/csipubs/compound_warfare.pdf vii.

[2] There were no German naval aviation assets. Gronning quickly appropriated all related maritime aircraft to the Luftwaffe and the two German aircraft carriers under construction were never completed.

Eric Raeder, My Life, trans. Henry Drexel, (Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1960), 154.

Robert Jackson, Kriegsmarine; The illustrated History of the German Navy in WWII, (London, Aber’s Books ltd 2001), 24.

[3] Jackson, Kriegsmarine, 23.

[4] Jackson, Kriegsmarine, 116.

[5] Terry Hughes and John Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, (New York, The Dial Press 1977), 20.

[6] Hughes and Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, 49.

[7] Hughes and Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, 123.

[8] Ibid, 125.

[9] Steury, “The German Naval Offensive,” 81-83.

[10] Cajus Bekker, Hitler’s Naval War, (Garden City, Doubleday and Company 1974), 141.

[11] Sturey, “The German Naval Offensive,” 81-83.

[12] Hughes and Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, 38-52.

[13] Assmann, Kurt. “Why U-Boat Warfare Failed,” Foreign Affairs 28, no. 4 (1950): 659-70. doi:10.2307/20030803 665, 667.

Hughes and Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, 304, 305.

[14] Hughes and Costello, Battle of the Atlantic, 304-305.

[15] A 1917 Imperial naval staff estimate. In Steury, The German Naval Offensive, 93.

[16] Based on a rate of 52,051 tons per quarter per U-boat deployed at a rate of 82.5 U-boats deployed in 1944. Hughes and Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, 304-305.

[17] Ibid, 49.

Hessler, Gunter, The U-boat War in the Atlantic, 1939-1945: German Naval History, (Great Britain, Ministry of Defense 1989), 12.

[18] Jackson, Kriegsmarine, 48-55.

[19] Hughes and Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, 304-305.

[20] Ibid, 2.

[21] Hessler, The U-Boat war in the Atlantic, 9.

[22] Ibid, 91.

[23] Karl Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten years and Twenty days, (Cleveland, World Publishing Company 1959) 132-133.

[24] Doenitz, 133-134.

[25]Ibid.

[26] Hughes and Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic, 304-305.

This includes U-boats launched after the bulk of Allied ASW efforts began to take effect.

[27] Bekker, Hitler’s Naval War, 381.

[28] Jackson, Kriegsmarine, 69.

[29] Jackson, Kriegsmarine, 69-77.

[30] Ibid, 77.

[31] Raeder, My Life, 138-139.

[32] Jackson, Kriegsmarine, 21-23.

[33] Jurgen Rohwer, “Codes and Ciphers: Radio Communication and Intelligence,” in To Die Gallantly; The Battle of the Atlantic ed. Timothy J Rynyan and Jan M. Copes, (Boulder, Westview press 1994), 38-38.

[34] Donald Steury, “The Character of the German Naval Offensive: October 1940-June 1941,” in To Die Gallantly; The Battle of the Atlantic ed. Timothy J Rynyan and Jan M. Copes, (Boulder, Westview press 1994), 81.

[35] Assmann, Kurt. “Why U-Boat Warfare Failed.” Foreign Affairs 28, no. 4 (1950): 659-70. doi:10.2307/20030803 www.jstor.org/stable/20030803 665, 667.

[36] Kurt. “Why U-Boat Warfare Failed,” 665-667.

[37] Steury, “The German Naval Offensive,” 84-87.

Featured Image: German battleship Bismarck in the Baltic Sea in May 1941. (Colorized by Irootoko, Jr.)