By Dmitry Filipoff

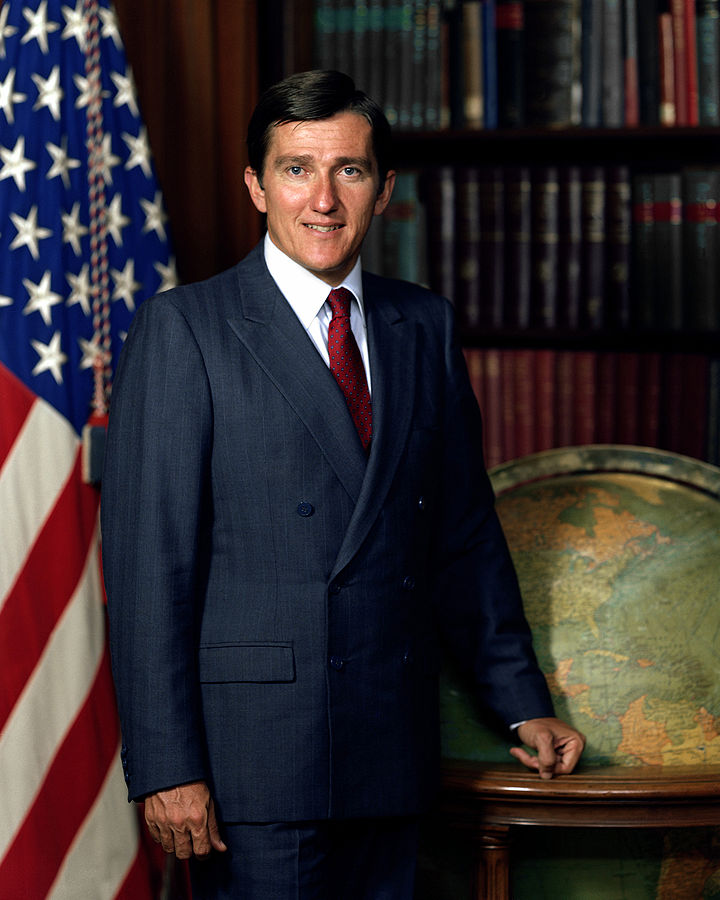

John F. Lehman Jr. served as Secretary of the Navy in the Reagan administration from 1981-1987. In this role, he advocated for the 600-ship Navy and went on to lead one of the most significant naval buildups in American history. In this interview, he recalls the critical elements that drove the Reagan-era naval buildup and what lessons can be applied to the new administration’s effort to build a 350-ship Navy.

In building up to the 600-ship Navy, what role did strategy play in informing budget? How did the 1980s Maritime Strategy help justify a naval buildup when many powerful voices argued against it?

Strategy played an essential role – arguably THE essential role. I spent years thinking about naval strategy before I became Secretary, sitting at the feet of masters, and I was able to hit the ground running to both promulgate and also implement that strategy through exercises at sea, within the context of President Reagan’s own well-thought-out goals, from the first day I was in office. I was blessed by CNOs who “got” strategy – especially Admirals Tom Hayward and Jim Watkins – and who developed and maintained a superb set of institutions and strategically-minded officers that were able to explain and carry out our Maritime Strategy from the get-go whether at sea; in Washington; in Newport, Annapolis and Monterey; and in Navy and joint commands all around the world. We were able to counter those “powerful voices arguing against it” time and time again.

How did you build a strong relationship with Congress and what arguments sustained their support?

We had many strong and experienced Navy supporters in Congress. First among them were Senators John Stennis, Scoop Jackson, John Tower and former SecNav John Warner. Our message to Congress was loud and clear: We had a disciplined logical strategy that would lead to American maritime superiority and success at sea. To carry out that strategy successfully, we needed a 600-ship Navy. And, recognizing that such a navy would undeniably cost money, we committed ourselves to fundamentally change Navy weapons development and procurement, bringing costs down dramatically.

We did this by restoring authority and accountability to officials, not to bureaucracies. Gold-plating and a change order culture were ended, which enabled fixed-price contracts and annual production competition. Navy shipbuilding actually had a net cost underrun of $8 billion during the Reagan years, the first and only time in history. Congress saw that we kept our word and did what we said we would, and gave us its support year after year.

The new administration is seeking to build a 350-ship Navy. What will it take to achieve this goal sooner than later, and should this buildup be used as an opportunity to augment existing force structure?

First, it will take immediate enunciation of a clear, compelling strategy. Next, as the fleet shrank from 594 to the current 274, the Defense bureaucracy has grown. Bureaucratic bloat must be slashed immediately through early retirement, buyouts, and natural attrition. Next, the kind of line management accountability that marked the Reagan years can end constant change orders and enable fixed price competition.

In addition to these deep reforms it will of course take an immediate infusion of more money. And it will take an immediate refocus on drastically ramping up competition within the defense industry

With regard to force structure, the Navy desperately needs frigates. We do not need more LCSs nor can they be modified to fill the frigate requirement. We do not need to have a wholly new design as there are several excellent designs in European navies that could be built in American yards with the latest American technology. Indeed, the now-retired Perry class could easily be built again with the newest weapons and technology.

Naval aviation needs more and longer range strike aircraft. The advanced design F-18 can help fill this need with a program to procure a mix of both F-35s and advanced F-18s with annual buys, effectively competing the two aircraft for the optimum lowest cost mix.

The Navy faces multiple competing demands for resources including deferred maintenance that is hampering readiness and insatiable combatant commander demand for greater capacity. Additionally, the rapid rate of technological change is opening up numerous possibilities for new capabilities. Where should the Navy prioritize its investments to ensure credible combat power going forward?

There are some who argue that the dismal state of readiness must be dealt with first, and then the procurement of a larger fleet after. That would be a mistake. The priority is to achieve balance. Readiness and sustainability must be dealt with simultaneously with embarking on procuring the necessary new ships and aircraft.

In the 80s I was a vocal proponent of 15 carrier battle groups. But I was no less an advocate for 100 attack submarines. The Navy defends the nation across the entire spectrum of conflict—from what my old shipmate CNO Jim Watkins called the “violent peace,” through deterring and controlling crises around the world, to fighting and winning wars and deterring nuclear holocaust. That’s a tall order, but a necessary one.

The Navy needs to be able to pummel targets ashore, land Marines and SEALs, sink submarines and surface ships, knock sophisticated airplanes and missiles out of the sky by the dozens, lay and neutralize mines, get the Army’s and Air Force’s gear to the fight, and use both hard kill and soft kill power to do all that, as required.

The force structure needed to perform successfully at sea across that range of operations is extraordinarily varied, and must be continually balanced and adjusted, as we did with our 600-ship force goal all through the 1980s. It can be done, and the new administration and Congress must do it.

Your time as SECNAV involved hard-fought battles with industry to ensure better and more cost-effective shipbuilding. How can the Navy better work with industry to facilitate a buildup and improve acquisition?

The Navy must get its procurement system under control. It must end gold plating and constant design changes. Industry cannot sign fixed price contracts unless the Navy has completed detailed design and frozen the requirements. When that is done the disciplines of competition and innovation can return. Shipbuilders can make good profits by performance, cost reduction, and innovation in such a disciplined environment.

Of the possible operational contingencies the Navy faces around the world, which poses the greatest challenge to the Navy in successfully defending American allies and interests?

Would that it were so simple. The Navy is the nation’s premier flexible and global force. It must be able to deter disturbers of the peace like Islamist terror, and potentially the Chinese, Russians, Iranians, and North Koreans, and to destroy their forces if deterrence fails. The Navy must meet them toe-to-toe all around the world wherever they stir up trouble.

True, during the Cold War, we focused – and appropriately so – on pushing Soviet naval bears back into their cages in the North Atlantic, the North Pacific, the Med, and the Arctic. But we also had to be prepared – and were prepared – to turn on a dime to carry out President Reagan’s orders in and off Lebanon, in Grenada and off Nicaragua, over Gaddafi’s Libya, in the Gulf during the Iran-Iraq War, and all over the world against Middle Eastern hijackers and terrorists. Simultaneously we were engaged in saving hundreds of lives rescuing Vietnamese boat people in the South China Sea, and performing many other humanitarian missions around the globe.

What strategic and operational concepts would best apply naval power to today’s threats and adversaries?

To reestablish maritime supremacy and “Command of the Seas.”

The size, deployments, and capabilities of the U.S. Navy are indicative of America’s chosen role in world affairs. What would it mean for the Navy if the incoming administration adopts isolationism?

Despite occasional tweets to the contrary, an administration that has sworn to protect its citizens and businesses everywhere, renegotiate trade deals, and destroy ISIS cannot be characterized as “adopting isolationism.” Such a policy is unthinkable today.

200 years ago, Thomas Jefferson tried to get by with isolationism on the cheap, invested in a fleet of low-end gun-boats of limited value, and set his successor James Madison up to fight the War of 1812 to no better than a draw.

A little more than 100 years later, a succession of administrations adopted isolationism as their policy and disarmed their by-then world-class Navy through bad international treaties and worse budgets. As a result, the Navy struggled during the first two years of World War II before hitting its stride and surging to victory (read Jim Hornfischer’s and Ian Toll’s recent books for how we did that).

Threats to the nation won’t go away just because the country may turn inward. They will just try to push the country back across the oceans and then keep pushing ashore. American naval supremacy will guarantee that can’t happen.

What final advice do you have for the next Secretary of the Navy?

Have a sound strategy, and stick to it. Have a robust but achievable force goal. Cut costs and increase competition everywhere you can. Balance and adjust the fleet among all its competing missions, regions, and levels of conflict, and above all, ensure the capability to deter or defeat the most dangerous potential enemies of our nation. The new secretary must immediately go on the offensive against bureaucratic bloat, against sloppy contracting, against gold-plating and for fixed price production competition, and technological innovation through block upgrades.

While engaged in this righteous offensive he must constantly explain and articulate his strategy, his objectives, and his vision to Congress, to the Sailors and Marines, and to the American people.

The nation elected a new President with a set of clear and purposeful goals. The Secretary of the Navy must ensure that – under his charge – the nation’s Navy becomes stronger and readier to carry them out.

The Hon. John F. Lehman Jr. is Chairman of J.F. Lehman & Company, a private equity investment firm. He is a director of Ball Corporation, Verisk, Inc and EnerSys Corporation. Dr. Lehman was formerly an investment banker with PaineWebber Inc. Prior to joining PaineWebber, he served for six years as Secretary of the Navy. He was President of Abington Corporation between 1977 and 1981. He served 25 years in the naval reserve. He has served as staff member to Dr. Henry Kissinger on the National Security Council, as delegate to the Force Reductions Negotiations in Vienna and as Deputy Director of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Dr. Lehman served as a member of the 9/11 Commission, and the National Defense Commission. Dr. Lehman holds a B.S. from St. Joseph’s University, a B.A. and M.A. from Cambridge University and a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. He is currently an Hon. Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge University. Dr. Lehman has written numerous books, including On Seas of Glory, Command of the Seas and Making War. He is Chairman of the Princess Grace Foundation USA and is a member of the Board of Overseers of the School of Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Nextwar@cimsec.org.

Featured Image: Secretary of the Navy John Lehman aboard USS Iowa in July, 1986.