By Drake Long

Countries are beginning to pay more attention to their dependence on rare earth metals. Rare metals like cobalt and nickel are sought out for their applications in smart phones, electric car batteries, and countless other gadgets, but come from an exceedingly small number of places, – virtually all of which are within the borders of the People’s Republic of China or under the control of its state-owned enterprises. This sets up a worrying imbalance in an extremely crucial supply chain that any advanced economy relies on.

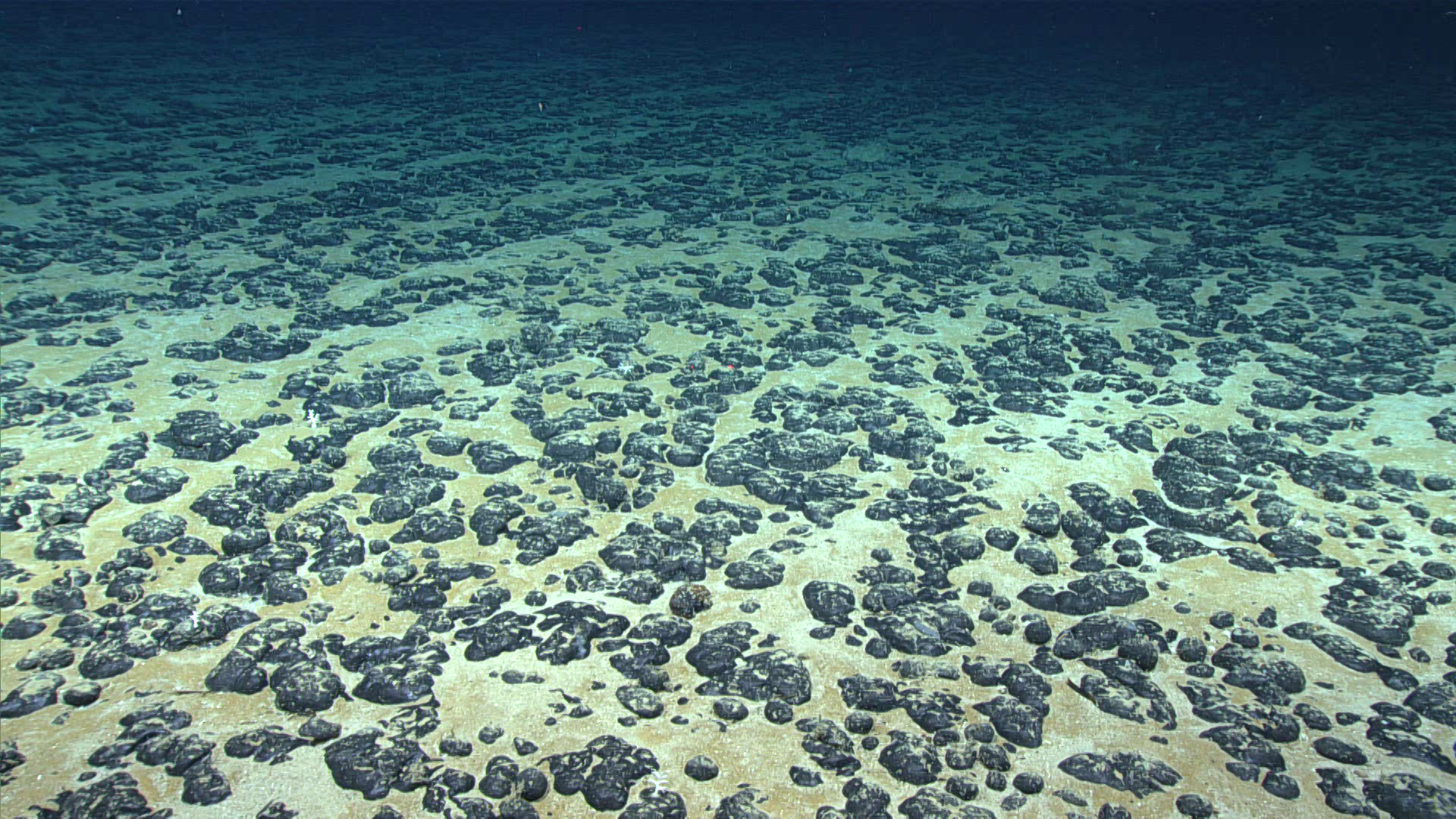

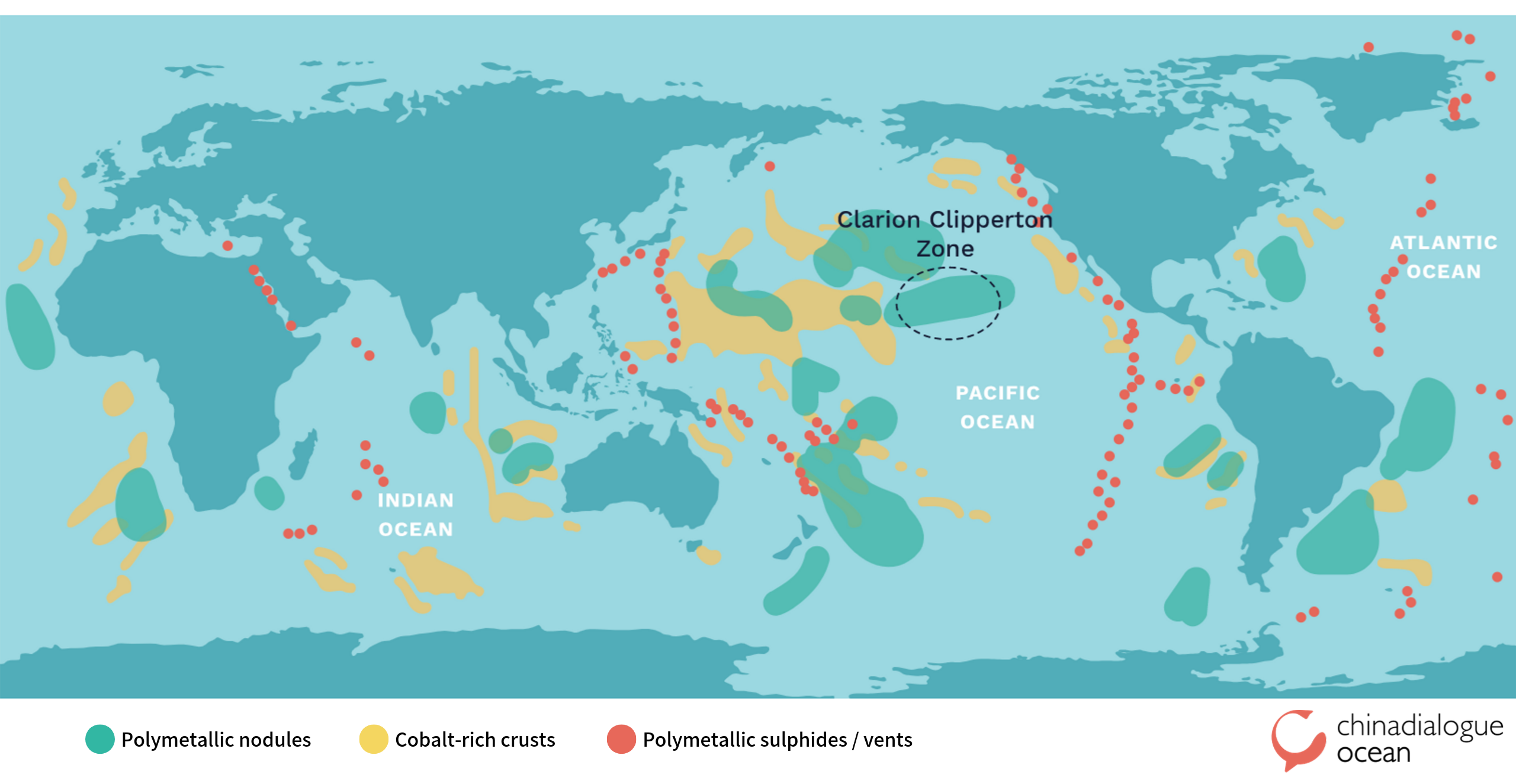

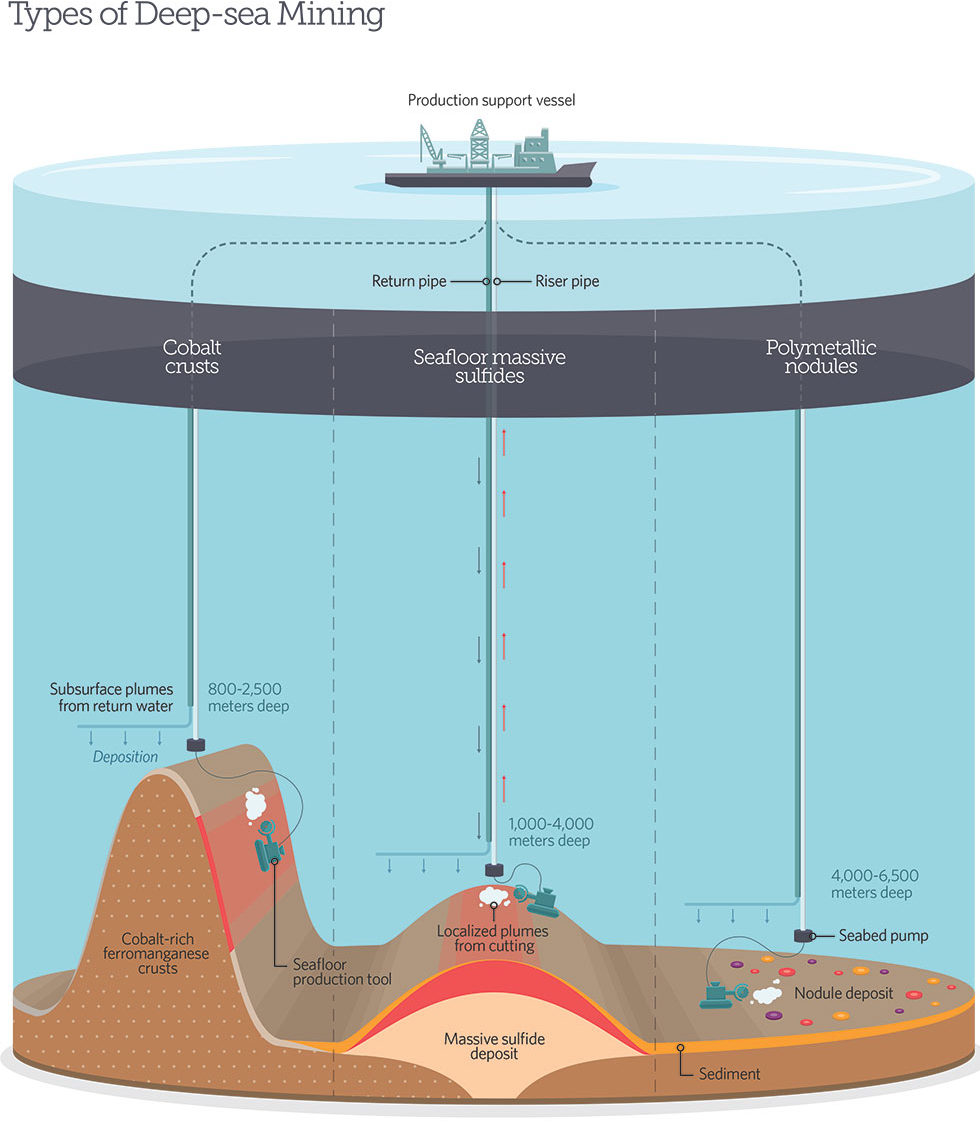

There is one potential solution that has come up time and time again: mining the seabed. Unbeknownst to many, the bottom of the ocean holds deposits of rare metals that could scratch the tech-hungry world’s itch, and most of these resources are finally becoming accessible for the first time. These deposits usually take the form of polymetallic nodes sitting on certain parts of the seabed, or as crusts surrounding hydrothermal vents.

There is some wisdom in wanting to decrease one’s reliance on China for something as critical as the components that power almost every electronic device, given China’s history of economic coercion. There is also an understandable fascination with tapping a mostly untouched area like the seabed.

One way to think of the deepest, darkest parts of the world’s oceans is as a new frontier, similar to the thawing Arctic or the yawning abyss of space. There is a shortage of scientific and strategic understanding of the seabed’s value, even as humankind eagerly throws itself into the water to develop blue economies based on marine resources.

The deep sea is rapidly approaching an era reminiscent of the gold rush period of the American West, when pioneers could potentially strike it big solely by venturing out to where few others wanted to go. The risk is high, but the rewards are potentially massive – if one could get seabed mining to scale.

The problem is that nobody should be mining the seabed anytime soon. The looming environmental cost is monumental, and the race for seabed resources could reinvigorate any number of maritime disputes. Is seabed mining really worth the trouble?

A Steep Environmental Cost

Currently, seabed mining is limited to some massive state-backed projects in China and India, and to some Australian or Canadian start-ups with less-than-impressive records. There is also a major regulatory gap when it comes to seabed mining practices, which is meant to be filled by the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

The ISA was mandated to handle seabed issues by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). UNCLOS, at the time of its drafting, was ill-equipped to codify an equitable way to handle seabed mining, especially since the technology at the time didn’t enable any country to have a full sense of seabed resources or how to extract them.

UNCLOS passed responsibility to the ISA, which has the uncanny mission of handing out licenses and devising an entire regulatory framework for all seabed mining in international waters. That is a tall order for what is, by any stretch of the imagination, a very small UN agency.

The ISA has been plugging away at one comprehensive seabed mining framework for years now – the Mining Code. The Mining Code will set out how and when countries and companies can prospect for seabed minerals and eventually commercially extract them.

The ISA is working under a stressful deadline to get the Mining Code finalized later this year and allow companies to begin plowing the seabed. By its own estimates, the ISA believes larger-scale commercial extraction of seabed minerals will start around 2027.

However, the Mining Code will instead give a green light to companies to damage the ocean floor beyond all repair.

The concept that there is an environmentally responsible way to mine the seabed is highly dubious. A test that attempted to shed light on this dilemma ended up permanently scarring seabed ecosystems for years. The 1989 DISCOL test used an eight-meter-wide plough harrow to rake the center of an 11-square-kilometer plot in the Pacific Ocean, and is still considered to be the most advanced seabed mining trial to date. But ecosystems in the area haven’t recovered more than 30 years later. According to ecologist Hjalmar Thiel, who organized the DISCOL test, “The disturbance is much stronger and lasting much longer than we ever would have thought.”

Most of the world’s seabed hasn’t even been mapped, and countless deep sea environments on the bottom of the ocean lay waiting to be discovered. What is known to an extent is that the organisms living in these areas constitute some of the most fragile ecosystems on the planet, making any minor change in their environment potentially catastrophic.

https://gfycat.com/celebratedhomelydodo

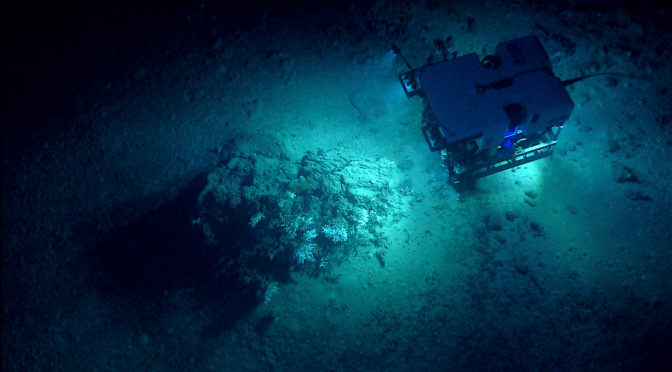

Remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer examines deep sea ecosystems (Video via National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

Case in point – the scaly-foot snail only lives at three very specific underwater hydrothermal vents on Earth. The snail had barely been discovered before its home was dug up for potential metal deposits, forcing the fascinating, rare creature onto the endangered species list.

The snail is one example of a near-extinction we knew happened. If seabed mining were to scale up to the commercial stage and plows began dragging back and forth over a seafloor that is poorly understood, then there would be countless other creatures and ecosystems that could be endangered or even thrown into extinction. And humankind likely wouldn’t even be aware of it until it is too late.

Aside from the environmental impacts, there is the question of how seabed mining will progress within national borders, where the ISA has no authority beyond setting an example. For a cautionary look at how this race for new resources can progress, it is best to look at the country poised to start seabed mining before anyone else – China.

China’s Maritime Dreams

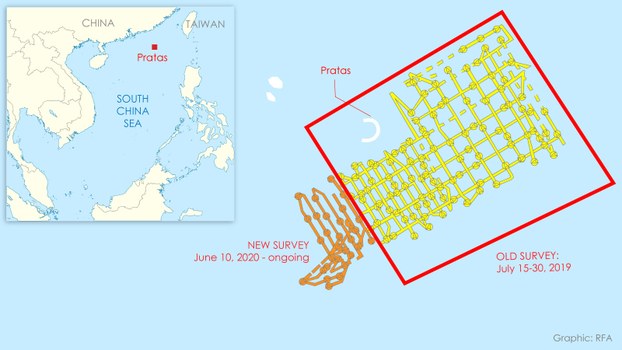

China has made it eminently clear it takes the resource potential of the seabed seriously, and frequently seems to flaunt its topographical knowledge of the ocean floor to its neighbors and other claimants surrounding the South China Sea.

For example, in April China released a list of Chinese-language names and locations for some 55 new undersea features – seamounts, underwater canyons, and others – in the South China Sea. China seems to treat the naming and placement of undersea features as a specious way to supplement its ambiguous historic rights argument, which China insists entitles it to nearly all of the rocks, waters, and seabed in the South China Sea. That line of reasoning was decisively struck down in a 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling, but China has never backed down from trying to justify its maximalist claims.

Maritime features recently named and listed by China [Click to expand] (Gif via RadioFreeAsia/Google Earth)

This cluster of undersea features listed in April closely tracks with a provocative survey China conducted last year within Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone.

That survey roped in a flotilla of coast guard ships and maritime militia, employed by both Vietnam and China, and sparked a tense stand-off between the two countries. China has regularly used survey vessels for its pressure campaigns against other claimant states in Southeast Asia. The aim of this harassment is to keep other Southeast Asian nations from exploring and exploiting resources within their waters. But in an area like the South China Sea, where the vast majority of the seabed is unmapped, the use of survey vessels and the curious publishing of lists of undersea features sitting on other countries’ continental shelves conveys another message – China knows what’s out there, and other countries in the region do not.

China’s information advantage on the ocean floor comes from investing heavily in deep sea research in recent years, and from employing the world’s largest fleet of survey vessels. The capability gap between it and its neighbors is wide and unlikely to be closed anytime soon.

China views the deep sea environment as a critical part of the marine economy, which encompasses virtually everything from fishing to submarine cables to genetic material used in state-of-the-art biomedicine. At the same time, the ostensibly civilian mission of deep sea research vessels allows China to send ships well-within the economic zones of other countries without potentially provoking a naval skirmish – thus making research vessels another element of China’s maritime insurgency against other claimants in the South China Sea, similar to the notoriously muscular China Coast Guard (CCG) and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM).

There are military applications as well, such as how topographical knowledge of the seabed makes it easier to chart paths for submarines and to ensure those submarines move around undetected.

Seabed mining is a logical priority if China wants to maintain its dominance over rare earths, as metals like cobalt and nickel are critical components for electric vehicles and smartphones, and are found on the ocean floor and in very few other places.

The issue seabed mining enthusiasts should first consider is that these ventures can serve as yet another arena for confrontational behavior in already tense waters.

Seabed mining is not cheap – the kinds of investments necessary to make it commercially profitable by 2027 will necessitate massive subsidies and state support. China is ahead of the curve on seabed mining solely because its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) involved in seabed prospecting are so heavily subsidized they can afford to get involved in such a risky and speculative industry. Michael Lodge, general secretary of the ISA, stated that “I do believe that China could easily be among the first (to start exploitation).”

By nature of being so expensive, there is an incentive to protect seabed mining projects through extensive means. As a country securitizes the ocean around state-backed seabed mining platforms, those same state-backed companies are emboldened to operate further and further afield. They then become wrapped up in the push to assert maritime claims over the objections of neighboring countries. China’s approach to seabed mining may thus begin to look very much like its approach to oil and gas in the South China Sea, which has not been conducive to regional stability.

Couple all this with how the exact boundaries of many countries’ continental shelves are in dispute, and how those Pacific countries with a high probability of holding seabed minerals in their borders also have virtually no regulatory frameworks to handle a nascent industry like seabed mining. The end result is that many latent maritime disputes may suddenly burst back into prominence, and at a time when the region needs far less, not more, imbroglios over maritime resources and borders.

Solutions Are Needed

Seabed resources have a dangerous potential to become conflict resources, fueling disagreements over maritime boundaries across the ocean at a time when many overlapping continental shelf claims are unresolved.

There is a straightforward solution to get ahead of the problem – ban seabed mining. The international community and regional forums should promulgate a series of regional and international moratoriums on seabed mining within countries’ maritime borders immediately, and the ISA should stop issuing licenses for seabed prospecting in waters outside of any national jurisdictions. However, that outcome, while undoubtedly the best for the undersea environment and their marine ecosystems, is probably unrealistic.

One alternative is for the ISA to craft a strict environmental standard that denies any seabed mining company the use of plowing machinery on the ocean floor. If the upcoming Mining Code were to require all seabed mining to only happen through the individual collection of one polymetallic nodule at a time, then seabed prospecting and extraction will lose much of its commercial viability and revert back to being employed mostly for research purposes and perhaps the extraction of biological material necessary for pioneering new medicines.

The ISA could also demand the most stringent environmental impact assessments necessary before any seabed mining or prospecting takes place, reducing the speed of the commercialization of seabed mining to a snail’s pace and postponing exploitation by perhaps another 10-20 years.

Ultimately the ISA cannot be expected to do everything. The international community, and most especially those civil society groups most attuned to the dire environmental stakes facing the ocean in the coming years, should proactively shine a light on seabed mining wherever it takes place.

Every project and license should be documented, followed, and vigorously examined, so that when deep sea environments are irreversibly damaged and coastal communities are inadvertently affected, pressure can be exerted on those companies or countries responsible. That requires, most dauntingly, forging ties with environmentalist groups in those countries most rapacious for deep sea resources, wherever they may be.

Seabed mining cannot be allowed to take place without stringent environmental safeguards and enforcement mechanisms. At best, seafloor ecosystems will be irreparably ruined and only some species and ecosystems will go extinct. This is not an acceptable trade-off for an industry that, as of yet, has not proved itself to actually be commercially viable, and is mostly sustained by the largesse and subsidies of certain countries.

Conclusion: A Common Heritage for Mankind

Seabed governance is going to be one of the thornier issues for a humankind more dependent on the oceans and coasts in the future, and the foundation needs to be laid now for an approach that does not imperil the seabed’s ecosystem for a very dubious profit. National governments may be too indecisive to come to consensus, and international organizations like the ISA are ill-equipped to enforce anything even if they do have a change of heart or code. The process of better seabed governance begins with increased scrutiny, and will largely depend upon an alliance of marine environmentalist non-governmental organizations and the scientific research community.

The deep sea has always been and remains one of the most fascinating new frontiers on the planet, only accessible in the modern day because of incredible advances in technology. Let’s keep it how humanity found it – unspoiled.

Drake Long (@DRM_Long) is a 2020 Asia-Pacific Fellow for Young Professionals in Foreign Policy. He is a contractor for RadioFreeAsia, covering the South China Sea and other maritime issues in Southeast Asia.

Featured Image: Remotely Operated Vehicle Deep Discoverer passing over a rock outcropping. (NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014)

The true realities are somewhat different from what is set out in this article. This article is mainly correct for the south China sea, not for seabed mining as a whole. As far as the south China sea is concerned, I agree with author. But the article ignores the fundamental difference of mining in a country’s territorial waters and economic zone, as opposed to mining outside the economic zone of any country in accordance with the deep sea licenses issued by ISA. The article also ignores the most recent advances in mining equipment.

Hi, Thank you for the article. As someone who follows the industry, I found the information about China particularly interesting and unique.

That said, I believe that you’ve fallen into the same trap that many others have when writing about seabed mineral extraction. You have failed to put the issue into proper context. While there is no doubt that it will do irreversible harm to the mining footprint and some areas close by, if done carefully it will be far more sparing of the environment than terrestrial mining.

Our use of minerals is going to continue to expand – especially if we intend to fuel a green energy revolution. Electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, and battery storage will all require massive increases in minerals if we want to reduce co2 concentrations in the atmosphere. In fact, the World Bank projects that battery metal production will need to increase 500% over the next 30 years to meet demands. Some key minerals such as cobalt and rare earths, are simply not economically available in sufficient quantity from terrestrial resources to meet this demand. Trying to get these mineral,s out of the ground in terrestrial mines would lead to habitat destruction on a scale we have never seen before because yields would be so low and demand so high. Prices would rise to such an extent that we would have to go back to using gas powered cars and coal fired electric generation.

The reality is that seabed nodule extraction is remarkably low impact relative to land based mining. You aren’t mining in sensitive areas, such as hydrothermal vents. No, this is happening on the abyssal plains at 3,500m depth. There are small creatures that will be harmed within the mining footprint, but you would have set aside areas of about 1/3 of a license to make sure these colonies survive. You aren’t digging into the crust, but rather collecting rocks from the surface. You create a plume at depth – but if you do it right, you aren’t creating a plume anywhere else and you aren’t taking bottom water and depositing it on the surface.

Many environmental NGOs with whom I speak acknowledge that nodule extraction is the best way to supply the green energy revolution without doing massive damage to the planet in the process. All of us environmentalists need to get on board with this and understand these issues so that we don’t mistakenly stop projects that create the best results for humanity and the earth.

Please consider this the next time you publish. Thanks!

The world is desperate for cobalt. It fuels the digital economy and powers everything from cell phones to clean energy. But this “demon metal,” this “blood mineral,” has a horrific present and troubled history.

Then there is the town in northern Canada, also called Cobalt. It created a model of resource extraction a hundred years ago — theft of Indigenous lands, rape of the earth, exploitation of workers, enormous wealth generation — that has made Toronto the mining capital of the world and given the mining industry a blueprint for resource extraction that has been exported everywhere.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/57604568-cobalt

Good article and comments, There is a new book about Cobalt that is very important. Here is a recent interview on CBC Radio.

What a silver boom in the 1900s shows us about Canada today

Its silver boom rivaled the Klondike gold rush, gave rise to the Montreal Canadiens and was featured in Broadway shows. But the story of Cobalt, Ont. has faded from Canadian memory. Author and NDP Member of Parliament Charlie Angus revives the history of the town in his new book, Cobalt: Cradle of the Demon Metals, Birth of a Mining Superpower. He speaks with Chattopadhyay about his deep-seated love for mining towns, the blueprint Cobalt set for the industry at home and abroad, and how battles fought in the street 100 years ago can shape Canada’s future relationship with its natural wealth. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/sunday/the-sunday-magazine-for-january-30-2022-1.6331044