Notes to the New Administration Week

By Roshan Kulatunga

China’s national security strategy is shrouded in secrecy, making it challenging to access clear policy documents that shed light on its strategic ambitions. This need for reliable intelligence is underscored by China’s increasing interest in the Indian Ocean region, an area that has become a focal point of concern for U.S. policymakers and military strategists. The potential expansion of Chinese influence in this critical maritime zone raises alarms about the implications for regional security and U.S. interests, necessitating the development of effective counter-strategies to address China’s pursuit of gray zone warfare.

Gray zone warfare refers to activities that fall between conventional warfare and peace, often involving subversive tactics that can destabilize adversaries without triggering open conflict. China’s approach involves a systematic infiltration of various sectors, including technology, academia, media, and even political domains, to gather intelligence and insights into the strategies of possible adversaries. This multifaceted approach allows China to build a nuanced understanding of U.S. capabilities and intentions while subtly undermining them.

Chinese interests in Sri Lanka has extended to various levels of society. There has been extensive infrastructure development projects focused on roads, airports, seaports, energy facilities, telecommunications, and water supply systems. Most of these projects are funded through loans, while some key strategic initiatives are structured as direct investments. A significant portion of this development is driven by Chinese involvement, including state-owned enterprises, private investors, contractors, and laborers. This involvement raises concerns about economic dependencies and geopolitical leverage. The noticeable presence of Chinese nationals across critical infrastructure projects, when hiring locals would have often been sufficient and even more beneficial to the host nation’s economy, highlights the need for a thorough assessment of their roles. It is essential to investigate any potential subversive tactics, such as economic coercion, intelligence gathering, or long-term strategic positioning, that could impact Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and regional security dynamics.

Despite the growing body of literature analyzing gray zone tactics, there remains a significant gap in research that delves deeply into the specific methodologies employed by China in executing these tactics. Understanding the precise methods of infiltration and influence is critical for developing effective countermeasures.

China’s strategy involves expanding its influence across diverse societal domains, from cultural exchanges to economic investments, which serve to extract valuable information and develop points of leverage against the United States and its allies. To effectively counter these actions, it is imperative for the U.S. to conduct a thorough evaluation of China’s gray zone activities and to create robust, comprehensive strategies that address the multifaceted nature of these threats.

In addition, the United States must strategically leverage its intelligence networks, tapping into various sectors of society to gather insights, enhance situational awareness, and bolster its response capabilities. By doing so, the U.S. can better prepare itself to confront the challenges posed by China’s expanding influence and protect its national interests in an increasingly competitive global environment.

The alliance between the United States and India represents a significant counterbalance to China’s influence in the Indian Ocean region. This partnership is characterized by a shared commitment to promoting stability and security in a region that is increasingly strategic in global affairs. To achieve its objectives, China effectively utilizes an extensive intelligence network that spans the region, allowing it to gather crucial information on military deployments, economic activities, and political developments. However, the covert nature of China’s security strategies presents a considerable challenge, often concealing the critical information needed to properly interpret the intent behind its actions.

In general, the security interests and posture of the United States can be anticipated with a fair degree of accuracy due to the democratic principles underpinning its foreign policies and strategic decisions. These democratic mechanisms promote transparency and debate, thereby enabling allies and adversaries alike to gauge potential U.S. responses and how they may impact the rules-based order. In contrast, China’s approach to security is characterized by a more secretive methodology, which often complicates external analysis and understanding of its strategic ambitions. This fundamental difference in approach underlines the contrasting philosophies that guide the United States and China in their respective security strategies. The U.S. must manage this asymmetry as it develops strategies to counter China’s gray zone tactics.

Commander (Dr.) Roshan Kulatunga (ret.) served 22 years of distinguished service in the Sri Lanka Navy. Throughout his career, he held prestigious positions both at sea and onshore, including serving as the Editor-in-Chief at the Defence Web within the Ministry of Defence in Sri Lanka. He earned his PhD in International Relations from the University of Peradeniya in Kandy, Sri Lanka.

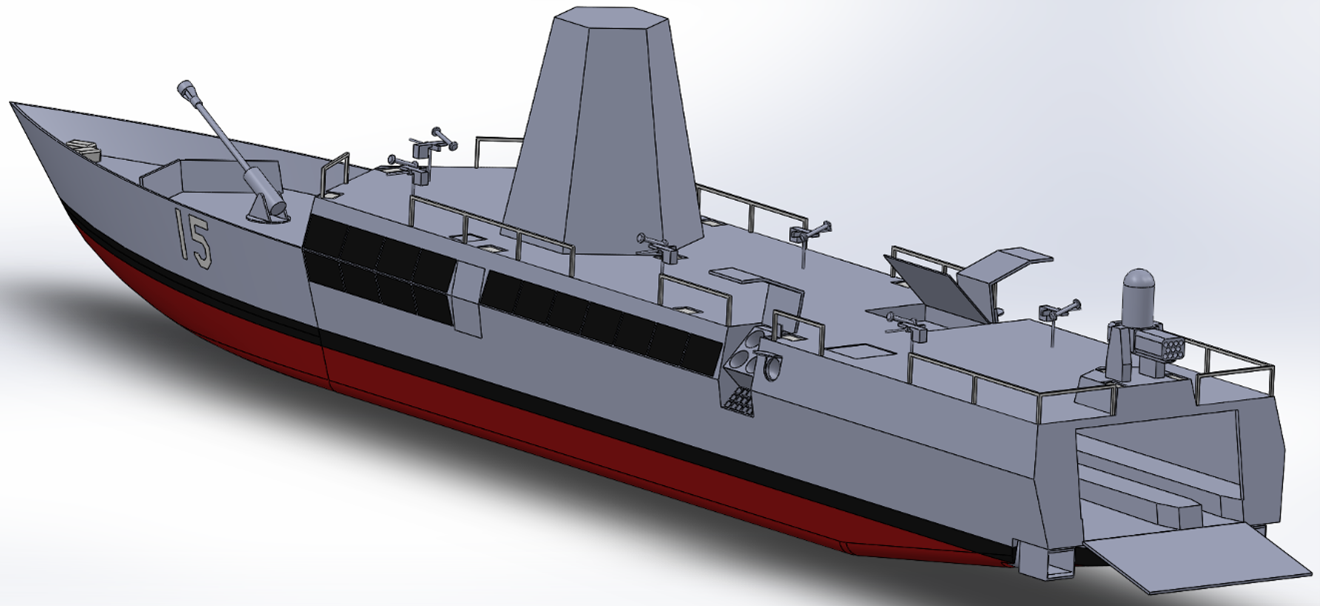

Featured Image: PLA Navy cadets from the Naval University of Engineering conduct an overseas visit mission on a Bangladeshi navy vessel, Oct. 13, 2024. (Photo by Ming Yongsheng/Xinhua)