By Robert Kitchen

China and the United States see each other as the pacing challenge,1 with Taiwan the obvious potential flashpoint. Correspondingly, different governments and think tanks repeatedly featured the Taiwan conflict in wargames. However, results from these studies varied significantly, ranging from swift Taiwanese capitulation and pyrrhic United States victories to bloody Chinese failures. This review compares several studies, explaining differences in the objectives, outcomes, and implications. As such, it is the first review to collate findings from a broad sample of wargames held over eight years between 2016 and 2023. It identifies a clear, regressive trend in the United States and Taiwanese chances of victory over the period and crucial factors influencing the outcomes for the People’s Liberation Army, the Republic of China, the United States, and allied forces. It concludes with recommendations for future wargame iterations.

This review focuses on published United States military rather than economic or non-kinetic influence studies. These studies were unclassified or substantively reported in open sources and addressed a conflict in the Western Pacific, usually involving Taiwan and the United States. However, similar studies were undertaken in China, Japan, and Taiwan, which have established military wargaming capabilities.2 The United Kingdom also has wargaming and net assessment capabilities.3 While this paper looks at published studies, it also includes officially announced insights about classified ones.

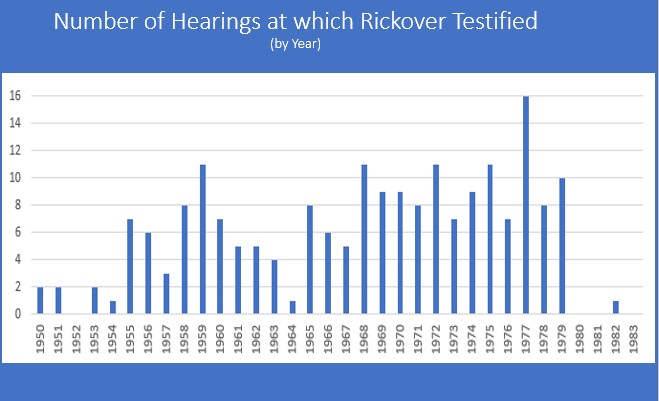

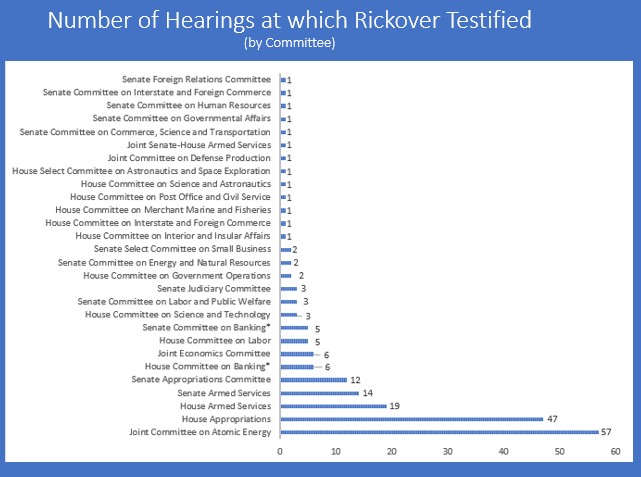

For comparison purposes, this review groups studies into three discrete eras: before 2017, 2017 to before Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and those conducted afterward. The timeframes were chosen as they represent three distinct trends. Pre-2018, wargames tended to end favorably for the United States, Taiwan, and allies, albeit at great cost. Between 2018 and February 2022, outcomes grew increasingly pessimistic for the United States and Taiwan, with only one victory, four losses, and two stalemates. Finally, in the two games since February 22nd, 2022, the immediate insights from the larger Russian invasion of Ukraine have tilted the outcomes towards the defender.

Each era is divided into three sections. ‘Overview of studies’ briefly summarizes outcomes and recommendations. ‘Insights and analysis’ provide an overview of trends, differences, and future areas for study. ‘Conclusions’ provides a focus for future United Kingdom iterations.

The studies table summarizes a range of twelve wargames across three distinct timeframes: three from pre-2018, seven from 2018 to February 2022, and two post-February 2022. Results are color-coded red when China can secure its objectives, yellow when objectives remain contested, and green when China cannot achieve its objectives against the Republic of China, the United States, and other opposition.

Studies Before 2017

RAND war with China, 2016.4 This study concerns four general cases of the United States and China’s conventional conflict in the East Asia region, a brief or long duration, and severe versus limited. It examines how specific systems (i.e., aircraft, surface ships, submarines, missiles, command and control) compare against each other. In the 2015 war games, Chinese losses were greater than those of the United States; however, the United States’ losses could be much heavier in a 2025 war.

The report recommended the United States increase interoperability and planning with allies, in part to increase its deterrent posture but also because it recognized that existing weapon stockpiles were insufficient to sustain prolonged campaigns. RAND recommended that the United States improve its ability to sustain protracted conflict to bolster deterrence and invest in more survivable force platforms like submarines and counters for anti-access systems.

RAND Scorecard, 2017.5 This detailed study created a scorecard and periodically examined United States and Chinese military capabilities in ten operational areas. By the last iteration in 2017, the People’s Liberation Army was considered inferior to individual United States capabilities, but its proximity to operations mitigated shortfalls. Based upon then-current trajectories, the United States’ dominance progressively receded over the next fifteen years.

The report suggested that the United States procure bases to improve dispersed redundancy and increase the survivability of aircraft, submarines, and space assets. The report also recommended intensifying diplomatic efforts to secure access to Southeast Asian countries, prioritizing building strategic depth through alliances.

The China Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia, 2017.6 Ian Easton’s book is still one of the best authorities on Taiwan’s military disposition. Many other studies cite its maps, especially vital beaches, and other assessments. Whilst not a net assessment, Easton lays out many building blocks for one. It also recounts the results of the Republic of China’s military wargames, which Taiwan could hold out in 2017 and 2018 simulations. The book uses primary sources to compellingly lay out the People’s Liberation Army and the Republic of China’s concept of operations, their assumptions, and the likely order of battle. It gives a good account of internal doubts within the People’s Liberation Army and the since lost bullishness of the Republic of China’s military. However, it is prescient regarding the trend in the military balance of power towards China.

The study’s recommendations advocate for the United States to support Taiwan. Still, it makes a compelling case that Taiwan’s position was defensible, and much could go wrong with an attempted invasion. Easton’s look at the captured lessons of the People’s Liberation Army indicates that chief of their concerns is the Republic of China’s long-range strike capabilities and projects to harden the Taiwanese islands, military facilities, and command and control capabilities. Therefore, long-range strike capabilities and infrastructure hardening need reinforcement. The book was relatively silent on preparations for operations other than the full-scale invasion of Taiwan. There were few, if any, lessons on countering People’s Liberation Army pressure campaigns through blockade, air incursions, or diplomatic isolation.

Studies from 2018 to pre-invasion of Ukraine

United States Marines wargame 2019.7 This United States Marine Corps wargame was set in Poland, South Korea, and Taiwan and forced the United States to react to simultaneous crises. Before the start of the game, the sides could invest in emergent capabilities such as artificial intelligence and quantum processing. The United States possessed insufficient forces and logistics to fight and win in all three conflicts simultaneously. Instead, the United States took a Europe-first approach, accepted risk regarding the Republic of China’s ground forces, and attempted to mitigate through naval and air assets. People’s Liberation Army forces were able to land in Taiwan but were unable to subdue the Republic of China and Japanese reinforcements. All theaters ended with local Russian or United States commanders seeking to employ nuclear weapons.

Reported classified Department of Defense (DOD) wargames, October 2020.8 One of the wargames of the series focused exclusively on the United States and People’s Liberation Army forces fighting over Taiwan. The United States Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff commented after the completion that the concentration of combat power for maximum efficiency and effect, and the United States military’s information dominance, is no longer guaranteed. After initial failures, the United States could reverse fortune by testing a new concept known as “expanded maneuver,” which involves the dispersal and disaggregation of combat power across all domains.9 The conclusion was the People’s Liberation Army benefited from extensive study of adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures over the previous two decades and implemented changes that challenged the previous way of war. The Department of Defense is pushing the United States military to adopt the expanded maneuver concept by 2030.

RAND Corporation comments to the media in August and October 2020.10 A RAND Corporation representative asserted that, in wargames set in 2025 and beyond, the United States loses assets in theater very quickly and cannot project power into the battlespace to defeat an invasion. Using multiple airborne and amphibious assaults, the People’s Liberation Army could reinforce a successful lodgement before effective United States assistance arrived.

Another report notes the United States could improve its chances by relying on a new generation of long-range anti-ship missiles combined with space-based reconnaissance. Additionally, using artificial intelligence to locate enemy targets and unmanned undersea drones that can fire torpedoes at the People’s Liberation Army landing craft could further blunt an attack. These capabilities reportedly could be achieved with about five percent of the current Department of Defense’s budget.

Reported United States Air Force wargame, Autumn 2020.11 In this wargame, the United States Air Force repelled a Chinese invasion of Taiwan set in 2030. The Air Force succeeded by using drones as a sensing grid, cargo planes dropping guided munitions, and other novel technologies, but with a large loss of life and equipment. Taiwan also increased defense spending before the conflict, buying drones and electronic warfare equipment. This outcome marked an improvement to similar war games held in 2018 over the South China Sea and Taiwan in 2019. In both those wargames, it ended in catastrophic losses. United States improvements in 2020 effectively deterred the People’s Liberation Army player from launching an invasion. The United States Air Force reportedly needed more and newer tactical aircraft, greater numbers of drones and ‘loyal wingmen’ teamed with crewed aircraft, and more strategic bombers, tankers, and airlift to win a war after 2030.

Center for New American Security Slaughter in the East China Sea, 2020.12 This limited study explored China’s seizure of one of the Senkaku Islands and the Japanese efforts to reclaim them. The United States assisted Japan but with constrained rules of engagement. Both sides sought to contain the crisis, but the conflict escalated nevertheless, culminating with the United States and Japanese forces being unable to reclaim the islands.

Center for New American Security Poison Frog, 2021.13 This study explored the Chinese seizure of Taiwan’s outlying Pratas Islands, which China quickly seized. The United States and its allies found few ways to push China out, without using escalatory military options, while economic and information campaigns failed. Close cooperation between Taiwan, the United States, and Japan could isolate China but did not lead to a return to the status quo. The report recommended close cooperation, clear deterrence policies, and Japan’s involvement.

United States Army-backed wargame blog, 2021.14 This United States Army-supported article provides a detailed narrative generated through a commercially available wargame. Ultimately, Taiwanese forces surrendered within a month. The People’s Liberation Army was able to utilize its modern, flexible forces near Taiwan, while their anti-access, area denial capabilities created problems that the United States forces were unable to overcome.

Studies post the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine:

Center for New American Security Dangerous Straits, June 2022.15 This study is set in 2026 and conducted a strategic-operational war game over Taiwan. Despite the People’s Liberation Army’s objective to decapitate Taiwanese leadership and inhibit a United States response with preemptive strikes on Japan and Guam, it indicated no quick victory for either side. Neither side had the upper hand after the first week. The wargame showed that a People’s Liberation Army presence in northern Taiwan possessed very vulnerable lines of communication. It also highlighted rapid escalation, crossed red lines, attacks on the Chinese and United States homelands, and a demonstrative nuclear detonation.

The study recommended the Department of Defense invest in long-range precision-guided weapons, undersea capabilities, additional basing in the western Pacific, and joint planning with Japan and Australia. It also noted the requirement to plan for a protracted conflict, mitigate escalation risks, and support Taiwan’s military posture.

Center for Strategic International Studies The First Battle of the Next War, 2022.16 This study is an impressively detailed and wide-ranging assessment of a war game involving China, Taiwan, Japan, and the United States. It examines conflict variations over twenty-four different iterations. It clearly details which factors increase or decrease Taiwan’s chances and is clear about assumptions and limitations. The study assessed that China was always able to get troops into Taiwan. People’s Liberation Army forces were so numerous and close that outright defeat at sea was impossible.

Conversely, the United States could not land any forces on Taiwan within the month the games were played. The studies found that the United States, Taiwanese, and Japanese forces prevailed if four key conditions held: Taiwan ground forces could hold out, Taiwan is properly supplied before a conflict, the United States could access bases in Japan, and the United States could rapidly strike the underway Chinese fleet. The study acknowledges that it is more optimistic regarding the chances for Taiwan and the United States, contrasting with some internal United States wargames (see above).

The study’s recommendations included clarifying war plans with Taiwan and Japan, expanding United States facilities near Taiwan, demonstrating a political willingness to incur heavy casualties, and preparing Taiwanese forces properly.

Trends over time. The reviewed wargame studies reveal a worsening trend for Taiwan and its defenders. The worrisome trend is especially pronounced for scenarios that take place in the period 2025-2030.17 Studies written before 2018 typically showed that the Republic of China and United States forces hold Taiwan at increasing cost. Studies after 2018 are more pessimistic, as the growing People’s Liberation Army capabilities and the inability of the United States to project sufficient power led to Taiwan’s defeat at worst or pyrrhic victories at best. However, this general trend is not uniform.18

The Russian invasion of Ukraine caused a reversal in this generally pessimistic trend. The latest studies reflect a greater uncertainty over the result of a Chinese invasion and the capabilities of its People’s Liberation Army. It became clearer that assessments need to model more factors, principally logistics, robust satellite-enabled communications, the introduction of greater numbers of uncrewed systems, and man-portable missiles. These factors all impeded Russia’s invasion. In recent studies, the changing character of warfare tended to favor a determined defender, which decreased China’s chances.

Whilst these newest studies are more optimistic for Taiwan, the identified general trend will worsen unless the United States enacts major improvements. Without massively increasing the number of missiles available and the ability to strike People’s Liberation Army transports, the Republic of China’s forces are overwhelmed. In most scenarios that assume the United States makes such changes, the coalition defeated a conventional amphibious invasion and maintained an autonomous and democratic Taiwan; however, no study resulted in the successful retaking of lost Taiwanese territory by allied forces. A successful defense of Taiwan would come at a high cost. Allied forces lose dozens of ships, hundreds of aircraft, and thousands of service personnel while Taiwan’s economy is devastated. Such high losses would damage the United States’ global position for many years.19

Explaining differences between the studies. It is worth considering how these wargaming studies come to such a range of different results. Wargaming is a valuable tool for commanders, leaders, and managers. Well-executed wargames before and during hostilities delivered significant competitive advantages in numerous conflicts, although wargaming does not, and cannot, guarantee success.20 The United States, China, and Taiwan have all wargamed the issue of Taiwan extensively.21 But wargaming studies tend not to be done if the answer is self-evident and beyond doubt. For example, no wargame assumes Taiwanese forces are unwilling to fight as China could then accomplish its objectives quickly and consolidate control.

Therefore, distinct scenarios are used in the various studies above to seek insights in different situations. Conflicts may include various actors and involve basing from a range of countries. Involved parties would use different concepts of operations, like a deliberate full-scale invasion or limited attack on outlying islands, with different levels of strategic and tactical warning for defenders and reinforcers. One alternative approach involved letting a Chinese invasion run out to see how long Taiwan could hold on while assuming some best-case scenario conditions for the People’s Liberation Army. The scenario provided insight into the allowable delay for the United States to intervene before the Taiwanese capitulation. The answer was thirty-one days after the initial People’s Liberation Army landings.22

This review does not cover how to conduct a wargame. Conducting wargames is covered in places like the Ministry of Defense wargaming handbook and the methodology sections of some wargame studies.23 However, setting assumptions is critical to validation and fidelity.24 Many factors need to be assumed, whether significant, like which parties are involved, or insignificant, like the chances a missile can knock a ship out of action. But even a relatively simple assumption could be initially in error or become outdated during a conflict as sides adapt their tactics. For example, the effectiveness of depth charges in the Second World War25 or the use of unmanned aerial vehicles in the sensor-kill chain in Ukraine were instances where initial assumptions did align with reality.26

Unless bound by a common rulebook, studies will make different assumptions. These can account for variations in results. The First Battle of the Next War, 2022, specifically looks at how its study differs from classified Department of Defense wargames.27 It asserts differences come from rival values attributed to the probability of kill, different aims and objectives of the wargames, the focus on shorter time frames (when United States forces are less ready), and assuming Chinese capabilities are more potent for a worst-case scenario hedging effort. Differences are exacerbated by changes in force structure, capabilities, and the relative power balance between the People’s Liberation Army and its adversaries in proximity.

Besides tactical probability of kill metrics, assumptions need to be made about other factors. Some will be easier to make than others. For example, the order of battle of all sides is unlikely to change significantly in the short term. Still, the organizers also need to assume which forces would be saved for other contingency operations. For example, forces reserved by the United States for Europe or for China to commit to the Indian border. Weapon stockpiles, the will to fight, the effectiveness of forces, the concept of operations, allied support, availability of future weapon systems, strategic messaging, and tactical warnings must all be decided and agreed upon by the adjudicators and players. Moreover, as wargames look further into the future, more unknown variables come into play, all of which will affect the play’s fidelity and outcome.

Each of these factors and variables could prove pivotal in a closely balanced conflict, to say nothing of the usual frictions. Furthermore, any general conflict involving the United States and China would likely include all domains of warfare at a scale not seen since the mid-20th century, cover a vast area of the western Pacific, and comprise actors using a range of new and some unknown and classified capabilities. Therefore, modeling a future United States versus China conflict is, perhaps, wargaming’s most difficult challenge.

Sensitivity analysis: What factors increase the chance the United States, Taiwan, and allies will prevail?

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” – Attributed to statistician George Box28

While many studies differ, combining their findings can give valuable insights into what factors may prove pivotal in a future conflict. The most compelling conclusions arise from sensitivity analysis, which attempts to understand how different assumptions affect the outcome.29 These studies’ usefulness comes from testing the effects of different assumptions, as they demonstrate what factors would most increase or decrease the United States and Taiwan’s chances of victory.

The Center for Strategic International Studies’ The First Battle of the Next War, 2022, is the single best example of the comparative analysis of sensitive variables and is worth looking at closely. The study ran twenty-five different games, testing several variables the study deemed most important.30 The Center of Strategic International Studies identifies four critical conditions for success: Taiwan’s people and military must effectively resist, Taiwan must have sufficient stockpiles at the start of the war, the United States must begin operations against China immediately, and the United States must be able to use its bases in Japan for combat operations.31 Without these conditions, allied missiles and United States submarines were insufficient to defeat an invasion.

The report discusses the effects of twenty-five variables. The most important variables benefitting the People’s Liberation Army invasion were an isolated and indecisive Taiwan, a neutral Japan, delayed entry of United States combat forces (as much as D+14), and few modern anti-ship cruise missiles available to counter-invasion forces. The most important factors that benefit Taiwan’s defense were the People’s Liberation Army not being as proficient in conducting amphibious operations or defending their ships from missiles, immediate combat operations from the Japanese Self Defence Forces, increased hardened aircraft shelters in Japan, and more airbases or airports to conduct operations from for the United States.

From reading the studies in this review, the author considers these variables the most likely to determine the outcome of a conflict involving China, Taiwan, and the United States. First and foremost, the role of Japan (and, to a lesser degree, other allies) will be fundamental to Taiwan’s survival for two reasons. First, it increases and disperses the number of bases the United States can operate from, and second, it increases the mass and number of allied forces opposing China. The availability of Japanese and other regional bases, like the Philippines, increases the survivability and ability to surge assets into the theater of operations. A few Chinese strikes could utterly disrupt United States operations with just Guam and the United States’ nearby aircraft carriers. Adding Japanese and possibly other allied forces to the defensive order of battle makes it easier to increase fire rates against Chinese aircraft, ships, and transports.

People’s Liberation Army Navy vulnerability, or the ability to absorb attrition, is the vital kinetic variable. The more long-range missiles the coalition possesses and can direct against People’s Liberation Army invasion elements, the greater Taiwan’s chances. “They need anti-ship cruise missiles, sea mines, mobile artillery, mobile air defenses, unmanned aerial vehicles… It comes down to sinking about 300 Chinese ships in about 48 hours”.32 However, projected production rates of missiles like the Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LASRM) and maritime strike Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) are limited, and in many wargames, the allies quickly deplete these specific missiles. The time needed to transport these missiles to relevant bases or ships affects wargame outcomes. If Taiwan has access to significant stockpiles of material at the start of the conflict, especially missiles, this buys Taiwan more time to await United States intervention. Additionally, with China’s anti-access capabilities limiting the effect of allied short-range air attacks, submarines offer an effective way to attack Chinese amphibious shipping. If United States submarines can reliably enter, engage in, escape, rearm, and return to Chinese shipping channels, Chinese chances for success are significantly diminished.

In most wargames without external support, the Republic of China’s forces remain effective only for a few weeks. Delays in the response of the Taiwanese, United States, Japanese, and allied forces significantly increased China’s chances. Delaying factors include allied indecision and the success of Chinese deception activities. While strategic surprise may be difficult to obtain, tactical surprise, like mounting an assault from fake exercises, increases China’s chances.

Fundamentally, the People’s Liberation Army and the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s success depends on two factors. First, China’s ability to project its anti-access capabilities further from its coast will make it increasingly difficult for the United States to deploy forces at sufficient ranges to affect the outcome of a conflict. The second factor is China’s ability to plan and execute an opposed amphibious assault. This is an important area of uncertainty identified in many studies where China’s inexperience could result in a disaster for them in numerous ways.33,34

Areas of most uncertainty that require further study

Wargaming on a Taiwan invasion inevitably has limitations. As noted earlier, the scope of this conflict could be vast. All operational domains and political, diplomatic, economic, and information effects are in play. Not all permutations of the assumptions nor the interdependent effects can be tested. For practical reasons, wargames tend to cover shorter periods than a conflict with the People’s Liberation Army might take. Furthermore, many developments in warfare were demonstrated in the Russia-Ukraine war, which wargames have only started to attempt to model.

Wargaming studies sometimes helpfully discuss what they do and do not model. For example, the RAND scorecard, which considers more aspects than most, does not consider ground combat or drones, and it does not model the effects of the threat of nuclear weapons.

At the strategic level, several variables have been marginalized or overlooked. Xi’s long rule and centralization of power follow the pattern of many other authoritarian leaders. A lack of robust internal challenge could lead to a greater chance of strategic misjudgments than wargames currently assume.35 One war game considered multiple crises simultaneously (Russia, China, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea).36 The West’s rivals would likely seek to take advantage of crises if they could, either during or after a conflict. The effects of nuclear weapons deterrence were replicated by players imposing limits on themselves, like restricting attacks against mainland Chinese assets,37 but this was rare. None of the other studies directly calculated the effect of the use of nuclear weapons, and their use was considered beyond the scope. Xi and the People’s Liberation Army likely took note of the effects of Russia’s nuclear threats against the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

While some wargames model how long it takes various actors to engage in conflict, few have enough players to test Chinese efforts to break up coalitions and their impact on a conflict. The permutations of those alliances and coalitions are also worthy of study; the United States, Japan, and Taiwan are well covered but are not the only variations. With enough notice and favorable dispositions, other capable actors could become directly involved, like forward-deployed submarines from allies. China fears a multi-front war, so more consideration to Indian contingencies could be given. The role of other regional actors in South and South East Asia should be considered as active participants or potential threats that China needs to reserve forces to counter. Further, the will to fight for Taiwan’s population (and China’s effectiveness in undermining it) beyond its leadership has rarely been considered in depth.38 Still, it would be a vital contributor to the assessment. Most studies assume attacks would be limited or not occur in the United States and Chinese homelands. Some do,39 but more study is warranted on how such attacks could escalate or be deterred.

Similarly, the role of People’s Liberation Army forces based outside China is not covered. The People’s Liberation Army currently has limited self-defense capabilities, and China’s main effort will be concentrated on Taiwan. But, in later time periods, People’s Liberation Army bases worldwide could complicate allied intervention.40 As many studies find the most critical period is relatively short, studies on the effectiveness of sanctions and blockades are rare. Studies that look at economic sanctions tend not to consider military action and vice versa.41 Despite numerous predictions of long-duration conflict, most wargames consider a shorter, tightly bound period. Should China fail to take Taiwan, the Chinese Communist Party would be unwilling to give up its claim and accept the outcome. What China would do next is an important area for study.42 Barring state or party collapse, China would seek to rearm and re-contest the war. After and even during a period of conflict, the need to replenish stockpiles and material will be acute and could be wargamed.

Most studies assume China will deliberately mobilize military and civilian assets, like civilian sealift, that would be readily noticed unambiguously by the Taiwanese and other nations. China has a clear incentive to reduce the predictability of its efforts by staging more realistic-looking exercises to gain tactical, if not strategic, surprise. China’s normalization of increased activities, exercises, and incursions near Taiwan complicates allied decision-making.43 Furthermore, the invasion of Ukraine showed that not all allies perceived the warning signs and came to different conclusions regarding Russia’s intent.44 Some studies examined sensitivity analysis in the competing doctrines of the People’s Liberation Army and the Republic of China’s forces. However, the effects of the operational inexperience of the People’s Liberation Army and Taiwan should be better tested, especially on critical amphibious landings. Any conflict is unlikely to follow established and conditioned doctrine dogmatically. Besides mobilizing for a full-scale invasion, China could choose different coercive measures against Taiwan, including island seizures (salami slicing),45 maritime or air blockade, missile bombardment to destroy leadership or undermine will, or a surprise air assault.46 The United States’ concepts of operations will also change.47 Fighting in and around Ukraine has shown a significant increase in the use of drones for direct attacks and tactical reconnaissance. Wargames have not caught up with the increasing number and use of drones on battlefields, including at sea. While some studies note the growing role of larger drones in the air and maritime order of battles, more assessment of the role of drones in direct attacks and tactical reconnaissance, especially at long distances over the sea, will be needed. The robustness of drone data in electronic warfare must be examined. Reliable and resilient communication networks are required. China could quickly degrade Taiwanese command and control. However, China warily noted Ukraine’s ability to utilize massive proliferated low-earth orbit satellite constellations, like Starlink or OneWeb. Chinese losses would increase if Taiwan’s communications and computing networks were more robust.

Conclusions

The wargaming and other studies reviewed here show a positive general trend over time for China. However, this is not a constant trend, and early findings from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine indicate China might encounter more problems than previously thought.

In most cases, wargaming studies still show that a China and Taiwan conflict, featuring a United States intervention, would be close run and incredibly bloody for all sides. There would also be severe effects on the global economy. If the People’s Liberation Army replicates these studies, they should have some deterrent effect on China.

The outcome of these studies is very sensitive to small changes, and the war in Ukraine demonstrated new developments and uncertainty. Further analysis is needed. However, those running wargames possess limited resources, so studies that last longer and cover the interactions of more types of capabilities in detail would be difficult to conduct.

Instead, a greater range of smaller studies, which each interrogate more of the areas of uncertainty identified above, is recommended. These should include wargames on what follows an initial failed Chinese invasion, different Chinese military options (especially blockades), and the use of drones and capabilities like Starlink or OneWeb. These studies could then inform assumptions used by the larger, more comprehensive wargames that happen periodically.

These smaller studies should include the potential benefits and risks of including more allies, like Australia and the United Kingdom. While the first weeks are crucial to the outcome, prior experience indicated that the United Kingdom will likely have capable maritime and other assets deployed in the western Pacific at the onset,48 and the planned Global Response Force49 will give the United Kingdom further options to reinforce regional allies within that pivotal timeframe.

Robert Kitchen is a First Sea Lord Fellow at the Royal Navy Strategic Studies Centre. He is also a U.K. Ministry of Defence Civil Servant with experience in U.K. Indo-Pacific policy and defense engagement. These views are his alone and do not represent those of the U.K. Ministry of Defence, Royal Navy Strategic Studies Center, or any other institution.

Endnotes

1. Jim Garamone, “Defense Official Says Indo-Pacific Is the Priority Theater; China Is DOD’s Pacing Challenge,” United States Department of Defense, March 9th, 2022. (Accessed August 23, 2023). https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2961183/defense-official-says-indo-pacific-is-the-priority-theater-china-is-dods-pacing/

2. For example, see: Tso-Juei Hei, “Taiwan Conducts Han Kuang 2022 Large-Scale Exercise,” Naval News, July 29th, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/07/taiwan-conducts-han-kuang-2022-large-scale-exercise/; & Joseph Yeh, “DEFENSE/Taiwan’s Han Kuang exercises to begin Monday with tabletop wargames,” Focus Taiwan, May 14th, 2023. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://focustaiwan.tw/politics/202305140007 & Elsa B Kania & Ian Burns McCaslin. “Learning Warfare from the Laboratory – China’s Progression in Wargaming and Opposing Force Training,” Institute for the Study of War, September, 2021. (Accessed, August 23rd, 2022). https://www.understandingwar.org/report/learning-warfare-laboratory-china%E2%80%99s-progression-wargaming-and-opposing-force-training. For a quick and easy breakdown of Taiwan’s Han Kuang exercises from 2000 – 2020, see Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_Kuang_Exercise#2020.

3. “Defence Wargaming Centre,” UK Ministry of Defence, April 23th, 2023. (Accessed August 23, 2023). https://www.gov.uk/guidance/defence-wargaming-centre; Press Release: “Announcement of new Director appointed to the Secretary of State’s Office for Net Assessment and Challenge (SONAC),” U.K. Ministry of Defence, May 6th, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 202). https://www.gov.uk/government/news/announcement-of-new-director-appointed-to-the-secretary-of-states-office-for-net-assessment-and-challenge-sonac

4. David C. Gompert, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, & Cristina L. Garafola. “War with China: Thinking Through the Unthinkable,” RAND Corporation, 2016. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1140.html

5. Eric Heginbotham, et al. “The United States-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power, 1996–2017,” RAND Corporation, 2015. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR392.html

6. Ian Easton. “The China Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia,” Project 2049 Institute, 2017.

7. James Lacey. “How does the next Great Power conflict play out? Lessons from a wargame,” War on the Rocks, April 22nd, 2019. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023).https://warontherocks.com/2019/04/how-does-the-next-great-power-conflict-play-out-lessons-from-a-wargame/.

8. Kyle Mizokami. “The United States Military ‘Failed Miserably’ in a Fake Battle Over Taiwan,” Popular Mechanics, August 2nd, 2021. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/a37158827/us-military-failed-miserably-in-taiwan-invasion-wargame/.

9. David Vergun. “DOD Focuses on Aspirational Challenges in Future Warfighting,” United States Department of Defense, July 26th, 2021. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2707633/dod-focuses-on-aspirational-challenges-in-future-warfighting/; & Brett Tingley. “Joint Chiefs Seek A New Warfighting Paradigm After Devastating Losses In Classified Wargames,” The Drive, July 27th, 2021. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/41712/joint-chiefs-seek-a-new-warfighting-paradigm-after-devastating-losses-in-classified-wargames.

10. “Defending Taiwan is growing costlier and deadlier,” The Economist, October 8th, 2020. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023. https://www.economist.com/asia/2020/10/08/defending-taiwan-is-growing-costlier-and-deadlier; & Richard Bernstein. “The Scary War Game Over Taiwan That the United States Loses Again and Again,” RealClear Investigations (August 17, 2020). Accessed August 23, 2023:

https://www.realclearinvestigations.com/articles/2020/08/17/the_scary_war_game_over_taiwan_that_the_us_loses_again_and_again_124836.html.

11. Valerie Insinna. “A United States Air Force war game shows what the service needs to hold off — or win against — China in 2030,” DefenseNews, April 12th, 2021. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.defensenews.com/training-sim/2021/04/12/a-us-air-force-war-game-shows-what-the-service-needs-to-hold-off-or-win-against-china-in-2030/.

12. Chris Dougherty, Susanna V. Blume, Becca Wasser, and Dr. ED McGrady. “Slaughter in the East China Sea’, Center for a New American Security, August 7th, 2020. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.cnas.org/press/in-the-news/slaughter-in-the-east-china-sea. Original publication: Michael Peck. “Slauther in the East China Sea,” Foreign Policy,August 7th, 2020. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/08/07/slaughter-in-the-east-china-sea/.

13. Chris Dougherty, Jennie Matuschak and Ripley Hunter. “The Poison Frog Strategy,” Center for a New American Security, October 26th, 2021. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-poison-frog-strategy.

14. Ian Sullivan. “337: ‘No Option is Excluded’ — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan,” Mad Scientist Laboratory, July 1st, 2021. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://madsciblog.tradoc.army.mil/337-no-option-is-excluded-using-wargaming-to-envision-a-chinese-assault-on-taiwan/

15. Stacie Pettyjohn, Becca Wasser and Chris Dougherty. “Dangerous Straits: Wargaming a Future Conflict over Taiwan,” Center for a New American Security, June 15th, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/dangerous-straits-wargaming-a-future-conflict-over-taiwans

16. Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, & Eric Heginbotham.”‘The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 9th, 2023. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.csis.org/analysis/first-battle-next-war-wargaming-chinese-invasion-taiwan

17. See “Defending Taiwan is growing costlier and deadlier,” The Economist, October 8th, 2020; & Richard Bernstein, Op Cit.

18. Valerie Insinna, Op Cit.

19. Mercy A. Kuo & Mark Cancian. ”Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan: ‘Victory Is Not Enough,”, The Diplomat, January 31st, 2023. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://thediplomat.com/2023/01/wargaming-a-chinese-invasion-of-taiwan-victory-is-not-enough/

20. Developments Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC). MOD Wargaming Handbook, UK Ministry of Defence, August, 2017. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/641040/doctrine_uk_wargaming_handbook.pdf. For a view of the effectiveness of wargames during war, see Simon Parkin. “A Game of Birds and Wolves: The Secret Game that Won the War,” Sceptre: London, 2019. Parkin explores the work of the Western Approaches Tactical Unit; a small team of Royal Navy Reserve and Women’s Royal Navy Service personnel credited with devising the tactics, techniques, and procedures for anti-submarine operations during the Battle of the Atlantic.

21. Elsa B. Kania & Ian Burns McCaslin, Op Cit.

22. Max Stewart. “Island Blitz: A campaign analysis of a Taiwan takeover by the People’s Liberation Army,” Center for International Maritime Security, June 13th, 2023. https://cimsec.org/island-blitz-a-campaign-analysis-of-a-taiwan-takeover-by-the-pla/

23. See Chapter 2, MoD Wargaming Handbook, Op Cit.; & Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, & Eric Heginbotham, Op Cit.

24. Elizabeth Bartels. ”Getting the Most out of your Wargame: Practical Advice for Decision Makers,” War on the Rocks, November 19th, 2019. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/getting-the-most-out-of-your-wargame-practical-advice-for-decision-makers/.

25. Raymond H. Milkman. “Operations Research in World War II,” Proceedings, Vol 94/5/783, United States Naval Institute, May 1968. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1968/may/operations-research-world-war-ii.

26. David Hambling. “How Drones Are Making Ukrainian Artillery Lethally Accurate,” Forbes, May 12th, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidhambling/2022/05/12/drones-give-ukrainian-artillery-lethal-accuracy/

27. Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, & Eric Heginbotham. Op Cit. p102.

28. George E. P. Box. “Science and Statistics,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 71 (356), 1976: 791-799. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080%2F01621459.1976.10480949.

29. Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, & Eric Heginbotham. Op Cit: 36.

30. See Annex A, Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham. Op Cit.

31. Mercy A. Kuo & Mark Cancian. Op Cit.

32. Richard Bernstein. Op Cit.

33. Eric Heginbotham, et al. Op Cit: 21.

34. Chapters 4 and 5 in Ian Easton. Op Cit.

35. Hal Brands. “Putin Has Fallen Victim to the Dictator’s Disease,” American Enterprise Institute, April 7th, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.aei.org/op-eds/putin-has-fallen-victim-to-the-dictators-disease/.

36. James Lacey. Op Cit.

37. Stacie Pettyjohn, Becca Wasser & Chris Dougherty. Op Cit.

38. The Economist. Op Cit.

39. Stacie Pettyjohn, Becca Wasser and Chris Dougherty. Op Cit.

40. Cristina L. Garafola, Stephen Watts, Kristin J. Leuschner. “China’s Global Basing Ambitions: Defense Implications for United States,’ RAND Corporation, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1496-1.html.

41. Charlie Vest and Agatha Kratz. “Sanctioning China in a Taiwan crisis: Scenarios and risks,” Atlantic Council, June 21st, 2023. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/sanctioning-china-in-a-taiwan-crisis-scenarios-and-risks/.

42. E.g. see Executive Summary in Stacie Pettyjohn, Becca Wasser & Chris Dougherty. Op Cit.

43. Bonny Lin & Joel Wuthnow. “Pushing Back Against China’s New Normal in the Taiwan Strait,” War On The Rocks, August 16th, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023).https://warontherocks.com/2022/08/pushing-back-against-chinas-new-normal-in-the-taiwan-strait/

44. Patrick Wintour. “Why are Germany and France at odds with the Anglosphere over how to handle Russia?” The Guardian, January 26th, 2022. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/26/nato-allies-policy-russia-ukraine-analysis

45. Chris Dougherty, Jennie Matuschak & Ripley Hunter. Op Cit.

46. The Economist. Op Cit; & David Lague & Maryanne Murray. “T-Day:The Battle for Taiwan,” Reuters Investigates, November 5th, 2021. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/taiwan-china-wargames/

47. Valerie Insinna. Op Cit.

48. Prime Minister’s Office. “Fact sheet: Trilateral Australia-UK-United States Partnership on Nuclear-Powered Submarines,” U.K. Government, March 13th, 2023. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus-13-march-2023/fact-sheet-trilateral-australia-uk-us-partnership-on-nuclear-powered-submarines; & Press Release: “H.M.S. Daring deployment to boost UK response to Philippines typhoon,” U.K. Ministry of Defense, November 12th, 2013. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://www.gov.uk/government/news/hms-daring-deployment-to-boost-uk-response-to-philippines-typhoon

49. U.K. Ministry of Defense. “Defence’s response to a more contested and volatile world,” HH Associates, 2023. (Accessed August 23rd, 2023). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1171269/Defence_Command_Paper_2023_Defence_s_response_to_a_more_contested_and_volatile_world.pdf

Featured Image: Fighter jets attached to a brigade of the PLA Air Force Xi’an Flying College taxi on the runway in an Elephant Walk formation before taking off for a flight training exercise in early February 2024. (eng.chinamil.com.cn/Photo by Cui Baoliang)