Fleet Warfare Week

By Major Robert Holmes, USMC

Introduction

As the nature of combat in the maritime domain continues to intensify– in terms of size, scale, complexity, and consequence – the U.S. Navy must seek out and implement numerous structural changes now if it wants to win the next fleet-level fight. Gone are the days of smaller naval formations, such as amphibious readiness groups or specified task units, acting as supporting forces that assist a land force’s limited objectives. The Navy’s numbered fleets must now prepare to assume the role of the primary supported unit in a major theater of operations, one that can integrate effects in all domains in pursuit of large-scale sea control. Significant changes can be made in how fleets integrate with the acquisitions process acquire capabilities and how they leverage non-Defense Department agencies. Purposeful and urgent action is needed now if the Navy is to win the future fleet-level fight.

Operational-Level Trends

Future great power war will almost certainly feature a requirement for large-scale and continuous sea control. This requirement for sea control stems from the likely objectives of future wars and the need to keep options open. Maritime access will be essential for projecting U.S. power into contested areas, maintaining vital links with allies, and for maintaining options for opening new fronts against adversaries. Adversary objectives will in turn hinge upon the degree of sea control they can secure in support of their critical objectives, such as invading Taiwan or threatening NATO partners from maritime flanks. Sea control will enable the broader fulfillment of the joint force’s objectives across multiple domains and will serve as a major operational-level objective in its own right.

This requirement for sea control is a marked departure from the wars the U.S. has fought since 1945. Vietnam featured practically no fleet combat, nor did the limited campaigns in Grenada and Panama. The U.S. deliberately ceded localized sea control during the initial stages of Desert Storm in order to prevent a premature maritime engagement, but commensurately allowed the Iraqis to mine sea lines of communication in their own coastal waterways.1 This then necessitated a time- and risk- intensive de-mining campaign after the cessation of hostilities with Iraq.2 The Global War on Terror and its two main fronts – Afghanistan and Iraq – likewise did not involve clashes over sea control. Neither country had a functioning navy to contend with and the U.S. Navy was able to provide support to land forces with relative impunity.

As the necessity for massive sea control increases, so too does the complexity of achieving it. The days of the decisive naval battle could be over, and the Navy may need to pursue a more cumulative campaign of gradually eroding the adversary’s combat power, much as how Ukraine has against Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.3 In support of such a campaign, the Navy’s fleets must find a way to mass the effects of their weapons systems and ISR platforms without massing the physical signature of their ships.

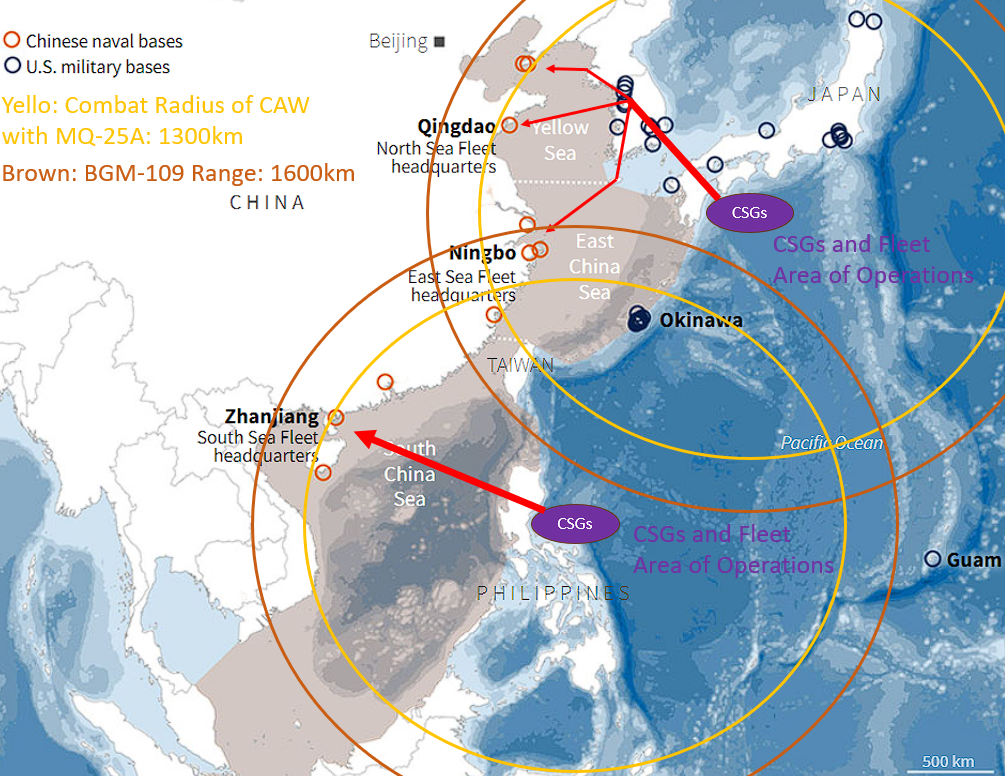

China’s approach to warfighting encourages this rethinking at a much larger scope and scale. China likely does not want to meet American fleets head-on in a massed decisive battle. China is currently establishing a defense posture, both on its mainland and throughout its near seas region, that could prevent hostile forces from massing for a decisive engagement while allowing China to fulfill regional objectives.4 In contrast to the prevalence of unmanned vehicles in Ukraine, China’s anti-ship missile arsenal is a powerful asset that is designed to keep American fleets at bay and at risk. By imposing this separation, China can secure sufficient freedom of action within a protected bubble and dictate the terms of potential engagements.

The difficulty of penetrating into China’s A2/AD bubble creates a challenging set of operational requirements for U.S. fleets. Fleets must now reach beyond their organic capabilities if they are to prevail in future fleet-level warfare.5 Other entities throughout the joint force, and even whole of government, will be needed to set conditions in their respective domains to help win future fleet battles. Direct engagement and liaison with numbered fleet commanders and their staffs will be necessary for many parts of government. As the major supported entity, fleets must now fulfill the role of the great integrator. U.S. fleets need to be ready assume the mantle of main effort across the joint force and be prepared for the responsibility of integration.

Deepening Fleet-Level Integration

The Navy can do several things now to manage the aforementioned operational problems, mainly the requirement of achieving sea control and facilitating cross-domain reach at long range. The first is the acquisition of technology. Numbered fleets must be more deeply involved in the acquisition and force development process, from the initial definition of requirements, to subsequent tactical development and training reform, to the actual employment of a specific capability in combat. This process as it stands now is too decoupled from the tactical end user, fleets included. The nature of fleet-level warfare compounds the negative effects of this decoupling, because while fleet warfare is fought at the tactical level, it is won at the operational level.6 This necessity for operational-level victory and the nature of its scope forces fleet commanders to employ a wide variety of capabilities with different spans of influence. This variety of capability difficult to reconcile into an integrated whole, especially when siloed vendors, program offices, and service leaders do not readily involve end-users until well after a capability is established and fielded. Fleet commanders are then put into the position of having to reconcile a wide range of capabilities into an integrated approach at the operational level of war, even if that level was not factored into the original requirements of the capabilities.

Tactical users of emergent capabilities are forced to receive a specific piece of equipment or capability, determine if it meets their needs, then determine how to employ it in combat. Follow-on corrective action and tactical development is often necessary to meet warfighter needs well after a capability has been declared operational. The efficiency and effectiveness of this process can improve substantially if end users, in this case, fleets and their commanders and staffs, are involved from the very beginning of the acquisitions process. Tactical and operational considerations should feature much more prominently alongside the technical and engineering considerations that usually dominate the early acquisition process. The more commanders are involved in the acquisitions of their own equipment and capabilities, the more prepared they will be to integrate them into their broader operational-level constructs.

The inverse of the above point is another benefit to this “early and often” method of acquisitions – the more in tune fleet commanders are with all of their capabilities and their originating requirements, the more prepared they will be when one or more of these capabilities is taken off the battlefield.7 The enemy’s vote can and will force fleets to fight not as they are when they leave port, but as they are when they commence combat operations. Commanders can build branch plans, much as they do now, concerning the removal of specific capabilities and their effects in time and space. Commands should know how to win if their weapons guidance systems are jammed, if they cannot communicate with lower echelons, if the information environment is heavily saturated, if space-based ISR is not available, or any number of possible contingencies. If a fleet commander and their staff has consciously built the requirements for their desired effects early enough in the acquisitions process, then they will likewise have time to build branch plans that use other capabilities to compensate for the loss of desired effects. This is akin to General Eisenhower’s prescient adage – “plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”8 The more involved fleet commanders are in acquisitions, the more prepared they will be to employ capabilities when most needed, and by extension, the more prepared they will be to prevail in combat despite the loss of these very capabilities.

The second focus area is fleet integration across the joint force and whole of government. The demands of long-range influence and cross-domain reach at the fleet level necessitates widespread integration of the fleet across many sectors of government. The Navy’s sister services are a logical starting place. If it is determined that a particular numbered fleet and its campaign for sea control is the main operational objective in a given theater, then other players in that theater should adjust to strengthen the influence of this fleet. U.S. Air Force bomber squadrons should have fleet liaison officers to influence targeting decisions and the joint fires process. Army ground combat formations could ensure their land-objectives explicitly support the fleet’s campaign for sea control, likely through the seizure of land objectives that may influence the fleet’s ability to maneuver, and providing sensor coverage and killchain support in key areas. The Space Force has a plethora of capabilities, both in terms of ISR and targeting that fleets could surely put to use. Finally, the Marine Corps is especially tailored for this integration, as its nascent operational concept, the Stand-in Force, is designed to support fleets by contesting key maritime terrain from concealed land positions, all in an effort to enable the fleet’s success. Many elements of the joint force needs to consciously appraise their ability to support numbered fleets as the primary supported actor in a major theater of operations.

The Navy should not stop at leveraging the support of only the military, as the rest of the government has unique abilities to help fleets fight. All U.S. State Department embassies have political and military staffs that can shape the political environment in which a particular war is fought, both before and during hostilities. The intelligence community and its web of agencies is a major resource when it comes to collection and targeting in all domains. The Department of Transportation can play a critical role in mobilization and surge support. Many other government departments and agencies need to consider how they can contribute to fleet actions and be thoughtfully integrated into the plans of fleet staffs. The net of liaison officers should be cast as widely as possible, with all enablers involved as early and often as possible in the planning process.

Conclusion

The main mover and doer in the Navy is the numbered fleet, and the time is now to better enable these fleets for successful maritime combat in the near future. The importance of sea control is only increasing as the world becomes more interconnected and America’s potential adversaries become more belligerent in the global maritime commons. China is setting challenging conditions for the future maritime fight, and these conditions are complicating matters for the Navy and its fleets. These complications create the requirement for long-range and cross-domain reach at the theater level. These realities compel the Navy to more fully integrate the fleets into both acquisitions and force development, and with a wider scope of government partners. Through these efforts, the U.S. Navy can prepare to assume a role it has not assumed since World War II, that of the joint force’s main supported force in a major theater of operations.

Major Robert Holmes is a MAGTF Intelligence Officer and Eurasian Foreign Area Officer stationed at the United States Embassy in Riga, Latvia. Before his FAO training, he spent his formative company-grade years at 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, where he commanded at both the platoon and company level. In addition to CIMSEC, his writings have also appeared in the Marine Corps Gazette and the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings.

References

1. Department of the Navy, Naval Warfare Publication 3: Fleet Warfare (Norfolk, VA: Naval Warfare Development Command, 2021), 31.

2. Department of the Navy, Naval Warfare Publication 3: Fleet Warfare, 31.

3. Department of the Navy, Naval Warfare Publication 3: Fleet Warfare, 33.

4. Robert Holmes, “The Navy–Marine Corps Team Must Prevent an American Moskva in the Pacific,” Proceedings 149, no. 2 (February, 2023): https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/february/navy-marine-corps-team-must-prevent-american-moskva-pacific.

5. Department of the Navy, Naval Warfare Publication 3: Fleet Warfare, 8-10.

6. Department of the Navy, Naval Warfare Publication 3: Fleet Warfare, 27.

7. Department of the Navy, Naval Warfare Publication 3: Fleet Warfare, 54.

8. Angel F. Garcia Contreras, Martine Ceberio, and Vladik Kreinovich, “Plans Are Worthless but Planning Is Everything: A Theoretical Explanation of Eisenhower’s Observation,” in Decision Making Under Constraints, ed. Martine Ceberio and Vladik Kreinovich (Switzerland: Springer Cham, 2020): 93-8.

Featured Image: Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70), Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Kidd (DDG 100), Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Sterett (DDG 104), Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) Murasame-class destroyer JS Kirisame (DD 104), and Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN) Sejong the Great-class guided-missile destroyer Sejong the Great (DDG-991) sail together during a trilateral maritime exercise, Nov. 26, 2023. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Isaiah M. Williams)