By Daniel Thomassen

Introduction

The maritime region centered on the South China Sea has been a vital international trade route and reservoir of natural resources throughout modern history. Today, its importance cannot be understated: half the volume of global shipping transits the area, competition for energy and fishing rights is intensifying between surrounding nations (with growing populations), commercial interests are increasing, and regional military spending increases lead the world. Rivalry over resources and security has triggered disputes about sovereignty and historical rights. China has used its increasing relative power to aggressively claim sovereign rights over two-thirds of the South China Sea within the so called “Nine-Dash Line.” Overlapping claims by the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan are being dismissed and have sometimes resulted in armed confrontations. Furthermore, the construction of artificial islands and significant military installations on reefs and rocks is underpinning Chinese sea control ambitions within the “First Island Chain.” This deteriorating security environment threatens regional stability, adherence to international law, and the freedom of the seas. Furthermore, it has the potential to escalate into conflict far beyond the levels of militarization and skirmishes between fishing fleets, coastguards and navies seen so far.

The U.S. has been deeply involved in the creation and management of the East-Asian state system since World War II, contributing to its economic progress and security arrangements, which include alliances with the Philippines, Japan and South Korea. Thus, the regional interests of the United States include freedom of navigation, unimpeded lawful commerce, relations with important partners and allies, peaceful resolution of disputes, and the recognition of maritime rights in conformity with international norms and law (with the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in particular).1 These principles are universally applicable and must be upheld every time and everywhere to be respected. Regional countries are now reconsidering the relevance and commitment of the balancing power of the U.S. in light of Beijing’s dismissal of American concerns and bilateral initiatives towards its smaller neighbors.

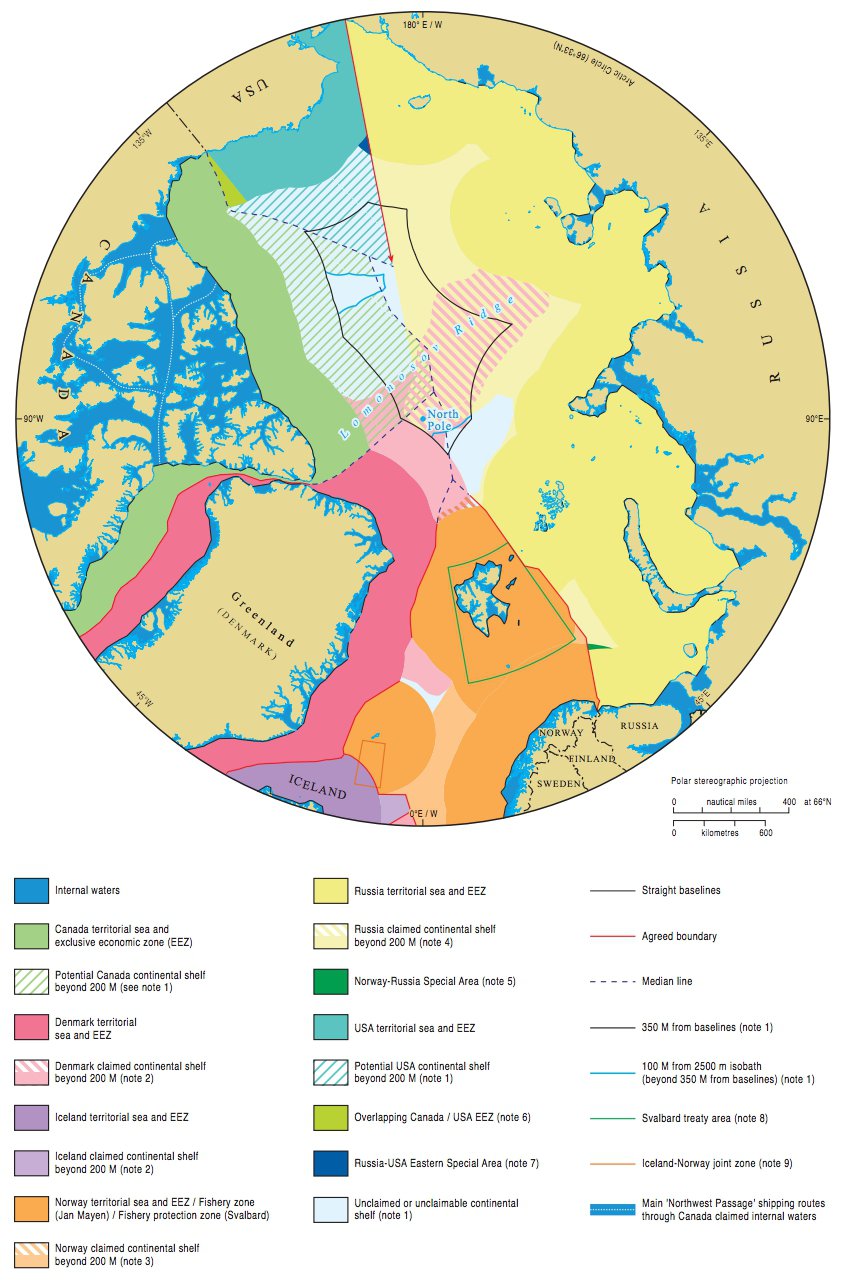

The Arctic region similarly holds the potential for great power rivalry, but in contrast offers a good example of peaceful settlement and compromise. The diminishing ice cap is causing a growing emphasis on resources, international waterways, and commercial activity in the Arctic, where there are also competing claims and great power security interests represented. However, the Arctic nations have chosen to cooperate with regards to responsible stewardship and use UNCLOS and supplementing treaties as the legal basis. The cooperative framework is constituted by the Arctic Council, the agreed adherence to international law and arbitration tribunals, bilateral and multilateral treaties, demilitarized zones, Incident at Sea agreements, joint fisheries commissions, as well as the power balance between Russia and the NATO alliance. As a result, although there is potential for competition and diverging national interests, mutually beneficial compromises and diplomatic solutions to maintain stability and predictability are preferred.

Arctic Dispute and Resolution

Currently there are overlapping claims from Russia and Denmark for the seabed under the North Pole (Lomonosov and Alpha-Mendeleyev Ridges) under consideration by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, and Canada is preparing another competing claim. These claims can further be used as a basis for bilateral agreements on maritime delimitations. This was the case between Norway and Russia in 2010, and there are prospects of a similar agreement between Russia and Denmark. Such cooperative mechanisms, institutions and shared principles in the Arctic are far more robust than comparable efforts in the Southeast Asia, such as ASEAN or the “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea.”

The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 set a standard for international governance, and was a bold and forward looking concept when introduced almost 100 years ago.2 The archipelago was discovered by Dutch explorers in 1596, and resources were since extracted by Holland, England, Russia, and Scandinavians. Eventually, the major powers voluntarily conceded sovereignty over the islands to the young Norwegian state through a commission related to the Paris Peace Conference after World War I. The Treaty allows visa-free access for citizens of signatory states, equal rights to extract natural resources, freedom to conduct scientific activities, ensures environmental protection, and prohibits permanent military installations. This agreement exemplifies the feasibility of imposing restrictions on sovereign authority, the accommodation of the interests of the parties, and adherence to non-discrimination principles.

Episodes of Confrontation

Much like the South China Sea, there have been clashes between the coastal states in the Arctic. Between 1958-1961 and in 1976, there was a state of armed conflict and diplomatic breakdown between the United Kingdom and Iceland over fishing rights. 3 The Royal Navy escorted British fishing vessels to confront the Icelandic Coast Guard in the contested zone. Shots were fired, ships were rammed and seized, and fishing gear was cut loose from the ships in heated skirmishes. However, on both occasions it was the stronger power that stood down to the weaker, as Britain finally recognized Iceland’s right to protect its resources after significant international diplomacy that included the forming of UNCLOS.

Other minor events in the Arctic include the 1993 Loophole dispute between Norway and Iceland, 4 and Hans Island, the only unsolved territorial dispute, which is under negotiation between Canada and Denmark. 5 The successful diplomatic de-escalation of these cases is in stark contrast to the clashes between China and its rivals in events like the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, 6 the 1995 occupation of Mischief Reef in the Spratlys, the 1988 battle over the Spratly Islands, the 1976 grab of the Paracel Islands, 7 and of course the blunt Chinese dismissal of the 2016 ruling from the International Arbitration Court against the legitimacy of the Nine-Dash Line claim. 8

China has mostly shown an uncompromising attitude in the South China Sea since the 1970s, without serious U.S.-led international efforts to check its use of force. But China too has occasionally demonstrated its willingness to forward claims to international arbitration bodies, such as its 2012 submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf regarding the East China Sea.9 However, that effort must be viewed in context of the ongoing efforts at the time to be accepted as observer in the Arctic Council.

Applying Arctic Lessons

The recent row between the Chinese and the U.S. Navy over an Unmanned Underwater Vehicle is symptomatic of the evolving problem, which must be addressed by the new administration in the White House. The South China Sea currently constitutes the primary global hotspot where major and regional powers’ vital interests and alliance commitments directly clash. A framework to manage this region must be negotiated by the two superpowers primarily and supported by the other involved nations. It requires the will to compromise and the pursuit of mutual interests while looking forward – a set-up which could benefit from the indicated transactional policy approach of President Trump. Any long-term solution would have to accommodate legitimate Chinese demands for security and resources. But, the U.S. must commit strongly by dedicating all available instruments of power (diplomatic, information, military, and economic measures) to impose negative consequences unless China is willing to negotiate from its strong position. Furthermore, the U.S. must uphold the same standards and make concessions itself.

It must therefore expediently ratify UNCLOS10 with its international tribunals and vow to respect the treaties that must be created to regulate sovereignty, demilitarization, commercial rights and responsibilities to protect fish stocks and the environment. Chinese concerns about the “One China Policy,” American forward basing, and policy on the Korean peninsula must also be on the table, as well as cooperation on regional trade agreements.

While state security can be achieved in the South China Sea through treaties, demilitarization, power balance and predictability, the conditions for prosperity flow from similar efforts. As demonstrated in the Arctic, good order at sea and responsible stewardship encourages investments and lay the foundation for cooperative ventures that are mutually beneficial. Uncontested sovereignty and fair trade regulations are incentives for developing expensive infrastructure necessary for harvesting resources under the seabed. The inevitable link connecting China and the U.S. is the economic dependency between the two largest economies in the world. So far, they have both unsuccessfully introduced regional free trade initiatives in order to create beneficial terms for themselves such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement and the Trans Pacific Partnership respectively. 11 An obvious flaw with these proposals is that they have excluded the opposite superpower. Since both countries are indispensable trading partners to most others, a cooperative effort to create trade agreements would benefit both and could not be ignored.

Although unresolved sovereignty issues in the South China Sea make it a tough case, there is a model to study and lessons to be learned in the cooperative management of the Arctic region (as well as the 1959 Antarctic Treaty and the 1936 Montreux Convention). However, controlling the impulses of a great power to dominate its surroundings requires a massive international diplomatic effort, creating alternative mutually beneficial conditions and a proper balancing of military power. Active U.S. presence and regional capability is fundamental to maintaining a balance and influencing the shaping of a cooperative environment. But first and foremost, there is a requirement for building trust and confidence through long term commitment to international cooperation, predictability and clear intentions. For a start, the good examples from the Arctic have been shared with China, Japan, India, the Republic of Korea and Singapore – all of which are involved or have vital interests in the South China Sea dispute – since they became observer states to the Arctic Council in 2013. Likewise, the U.S. can also benefit from its experience as an Arctic nation, and from the insight gained from holding the chairmanship of the Arctic Council since 2015. Moving forward, the Arctic offers successful governance lessons that can be applied to the South China Sea in order to maintain stability and ensure prosperity for all.

Daniel Thomassen is a Commander (senior grade) in the Royal Norwegian Navy. He is a Surface Warfare Officer serving as Commanding Officer of HNoMS Fridtjof Nansen (FFGH). He is a graduate of the Royal Norwegian Naval Academy (2002), U.S. Naval War College (2015), and holds an MA in International Relations from Salve Regina University (2015).

References

1. Jeffrey Bader, Kenneth Lieberthal, Michael McDevitt, “Keeping the South China Sea in Perspective”, Brookings, August 2014 https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/south-china-sea-perspective-bader-lieberthal-mcdevitt.pdf

2. Wallis, Arnold, Numminen, Scotcher and Bailes, “The Spitsbergen Treaty – Multilateral Governance In The Arctic”, Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe/Applied International Law Network, Arctic Papers Vol. 1, 2011 https://dianawallis.org.uk/en/page/spitsbergen-treaty-booklet-lauched

3. The Ultimate History Project, “A Serious Joke: Britain and Iceland Go to War”, http://www.ultimatehistoryproject.com/cod-war-britain-and-iceland-go-to-war-over-fishing.html

4. Thorir Gudmundsson, “Cod War on the High Seas – Norwegian-Icelandic Dispute Over Loophole Fishing in the Barents Sea”, Nordic Journal of International Law, 64: 557-573, 1995

5. Jeremy Bender, “2 countries have been fighting over an uninhabited island by leaving each other bottles of alcohol for over 3 decades,” Business Insider, 10. January 2016 http://www.businessinsider.com/canada-and-denmark-whiskey-war-over-hans-island-2016-1?r=US&IR=T&IR=T

6. Jane Perlez, “Philippines and China Ease Tensions in Rift at Sea”, The New York Times, 18. June 2012 http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/19/world/asia/beijing-and-manila-ease-tensions-in-south-china-sea.html

7. “Military Clashes in the South China Sea” http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/spratly-clash.htm

8. Matikas Santos, “Key points of arbitral tribunal’s verdict on PH-China dispute”, Inquirer, 12. July 2016 https://globalnation.inquirer.net/140947/key-points-arbitral-tribunal-decision-verdict-award-philippines-china-maritime-dispute-unclos-arbitration-spratly-islands-scarborough#ixzz4UQUrV9m3

9. Submission by the People’s Republic of China Concerning the Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf beyond 200 Nautical Miles in Part of the East China Sea http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/chn63_12/executive%20summary_EN.pdf

10. Eliot L. Engel and James G. Stavridis, “The United States Should Ratify The Law Of The Sea Convention”, The Huffington Post, 11. July 2016 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rep-eliot-engel/the-united-states-should_b_10930236.html

11. Lauren O’Neil, “Trade In Asia: The Liberalization Agenda – Where To From Here?”, Forbes, 13. December 2016

Featured Image: The Canadian Coast guard’s medium icebreaker Henry Larsen is seen in Allen Bay during Operation Nanook, in Nunavut on Aug. 25, 2010. (Sean Kilpatrick/Canadian Press)

There is a clear difference: all Artic Countries negotiate and act under UNCLOS. China denies this for the South China Sea.