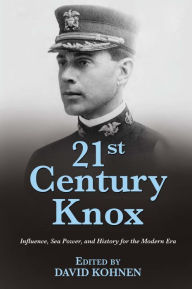

Kohnen, David. 21st Century Knox: Influence, Sea Power, and History for the Modern Era. Naval Institute Press, 2016 176pp. $24.95

By Dale Rielage

A century ago, Dudley Knox was one of the U.S. Navy’s up-and-coming leaders. His operational resume included combat experience in the Spanish-American War, the Boxer Rebellion, and the Philippines insurrection. In a generation that learned its trade from Mahan, Knox achieved intellectual distinction as an observer of naval command and control. Between the First and Second World Wars, Knox developed into one of the nation’s foremost practitioners of naval history, a respected commentator on maritime issues, and advisor to political and naval leaders. Through his professional associations, writings, and commentary, his influence reached to the battles of the Second World War and beyond.

It is precisely to rescue naval thinkers like Knox from obscurity that the Naval Institute Press began the “21st Century Foundations” series. In 21st Century Knox, David Kohnen has selected key writings spanning Knox’s more than fifty year career and combined them with a thoughtful introduction and commentary that places these writings in contemporary context. The result is a handy collection of short articles that speak both to the U.S. Navy’s history and to the challenges it faces today.

Knox came of age in a nation that was finding its place among the world’s great powers. The U.S. Navy was growing rapidly in capability, capacity and stature. While the new battleships that comprised the Great White Fleet were the most public face of President Theodore Roosevelt’s Big Stick, Knox himself preferred service on torpedo boats and destroyers, whose small size and independent operations offered maximum opportunity for initiative and responsibility. These smaller units also offered junior officers a glimpse of the challenges of coordinating multiple units in coordinated action – a challenge that was preoccupying Royal Navy leaders on the far side of the Atlantic.

Within the British Royal Navy, the tug-of-war between centralizing command and control and decentralizing authority had been playing out for more than a century. During the nineteenth century, the highly decentralized command style of Nelson had given way to a more centralized style, enabled by increasingly sophisticated means for signaling between units. Andrew Gordon, in his seminal study of the issue, noted how the trend towards centralization limited Royal Navy success at Jutland.

The U.S. Navy’s rapid growth in the 1880s and 1890s made command and control issues secondary to more fundamental issues of fleet proficiency and organization. Thanks to reform efforts spearheaded by Admiral William S. Sims, the U.S. Navy had significantly modernized its gunnery training – the foundation of applying combat power at sea at the time. However, this focus on the tools of tactical excellence had not yet expanded to a sophisticated system for managing large fleet actions.

It was the interplay between initiative and command that prompted Knox to produce his first significant writings. In 1913, then-Lieutenant Commander Knox placed in the U.S. Naval Institute annual essay contest with the article “Trained Initiative and Unity of Action.” It is no surprise that Knox, having experienced independent command as a junior officer, would instinctively support the decentralization of command. As a relatively junior officer, he dared to critique the current attitude in the service – a service which had enjoyed overwhelming victory and acclaim in its first modern combat experience against the Spanish Navy just fifteen years prior. “It is hardly necessary to enter into a description of our present system of command…it has never stood the supreme test of a large fleet action against a formidable enemy; and it is safe to say that even our greatest triumphs were accomplished in spite of glaring faults which most of us will candidly admit.” Knox then offered a detailed inventory of the impact of excessive control from above in both peace and war. Perhaps more perceptively, he asserted that detailed oversight invites unhealthy critique of seniors by juniors, where a delegated leadership style requires subordinates to own the actions of the team. Knox concluded his essay by asserting that the “initiative of the subordinate” should be the governing principle in U.S. naval doctrine and leadership.

It is important to note that Knox did not base his advocacy of decentralized control on the limitations of command and control mechanisms. In his mind, no improvement in the mechanics of command and control could meet the requirement for speed of action in the face of an adaptive enemy. As he wrote, “neither signals, radio-messages, nor instructions, written or verbal, can suffice…to produce the unity of effort – the concert of action – demanded by modern conditions in a large fleet.”

Knox followed his 1913 success by winning the Naval Institute Prize in 1915 with an examination of “The Role of Doctrine in Naval Warfare.” An examination of history convinced Knox not only that speed was critical in exploiting opportunity, but that command and control systems inherently degrade in combat. Well articulated and understood doctrine offers the first defense against this challenge, Knox asserted, by ensuring that subordinate commanders approach operations with the same basic assumptions. This doctrine should, in Knox’s mind, clarify for the force to what extent they should act offensively or defensively, as well as what actions should be carried out by the “primary force” (i.e. the entire fleet, with a focus on battleships) or the “secondary force” (i.e. mines, submarines, and small combatants). Knox emphasized that the development of doctrine should be a broad, collaborative process within the Navy in order to ensure buy-in from different communities and continuity of approach and investment across the tenure of different leaders.

Reading these two pieces, many readers will be impressed that they could be written today. Indeed, with minor updating in style and references, they could be published as commentary on today’s U.S. Navy. It is encouraging for today’s innovators that Knox did have profound influence on the culture and conduct of the U.S. Navy, albeit indirectly. Knox built a network of shipmates who were also interested in innovative ideas. Many of his friends, such as Ernest King, Earl “Pete” Ellis, Harold Stark, and Bill Halsey, would rise to positions of influence over the years. Knox’s work was also heavily influenced by his studies at the U.S. Naval War College, where he enjoyed the encouragement of Admiral Sims. Sims – himself the subject of another volume in the 21st Century Foundations series – and who offered an example of a passionate innovator who as a Lieutenant had written a letter to the President trying to drive improvements in U.S. Navy gunnery.

After Sims departed the War College for operational command in the Atlantic, he pulled Knox and a number of other promising young officers onto his staff. Shortly after, with the U.S. on the verge of entering the First World War, Knox was hand-selected to join Sims’ staff in London, placing him at the heart of the U.S. Navy’s first experience in modern coalition warfare. There, Knox was instrumental in tying U.S. Naval Forces in Europe into the Royal Navy’s extraordinary intelligence network. While an informal arrangement, it laid the groundwork for the “very special relationship” between U.S. and British naval intelligence during World War II.

By the 1920s, Knox’s philosophy of command and control had slowly moved from counter-culture to accepted doctrine. Knox’s articles became standard reading at the Naval War College and influenced the famous student wargames which contemplated naval war against Japan. Almost every senior navy leader in World War II attended the War College during this era was influenced by these games. In his outstanding history of naval command and control, Michael Palmer observes that the U.S. Navy would be exceptional in enshrining decentralized command and control and aggressive exercise of initiative in its doctrine. For example, Palmer notes that the U.S. Navy’s 1924 war instructions specified that “when attacked by an enemy, American ships were to turn towards the threat, and not away from it as had Jellicoe, in conformity with his own doctrine, at Jutland.”1

The summit of Knox’s indirect influence on his navy was reached on the eve of World War II. In his CINCLANT Serial 053 of January 21, 1941, Knox’s shipmate, Admiral Ernest King, instructed the entire Fleet that “initiative of the subordinate” was the “essential element of command.” King noted that he had “been concerned for many years over the increasing tendency…to issue orders and instructions in which their subordinates are told “how” as well as “what” to do to such an extent and in such detail that the ‘Custom of the Service’ has virtually become the antithesis of that essential element of command.” The Navy was close to war, King wrote, and the force was often “reluctant (afraid) to act because they are accustomed to detailed orders and instructions.” If this tendency was not reversed, asserted CNO King, “we shall be in a sorry case” when war arrives. Reversing this tendency required strong leadership, but ultimately the U.S. Navy’s victories in World War II were in no small part due to a culture of finding the right commanders and allowing them latitude to conduct combat operations with a deliberate economy of detailed higher headquarters direction.2

As Knox grew more senior and moved into retirement, his professional focus shifted to history and naval commentary. It is fair to say that today Knox is mainly remembered for his efforts to establish naval history as a discipline and to motivate the U.S. Navy to preserve its own history. That reputation, however, obscures Knox’s ongoing influence during his “historical” period. During the interwar years, a close relationship existed between naval intelligence, naval history and planning; and Knox was a regular if unofficial advisor of naval decision makers through the end of World War II.

If there is a weakness in this book, it is that Dave Kohnen sometimes comes across as a historian admiring another historian. Knox was a practitioner, a status that made him acutely interested in the impact of this analysis. Nonetheless, in making Dudley Knox readily accessible to the current generation of naval professionals, Kohnen and the Naval Institute Press have done a significant service. With the Chief of Naval Operations calling for the U.S. Navy officer corps to read, write, and fight, Knox offers an example of how an officer with ideas and the willingness to challenge the status quo can have a profound influence on the U.S. Navy. CIMSEC is one place for that writing to find a voice today – and 21st Century Knox is a great place to start reading.

Captain Dale Rielage serves as Director for Intelligence and Information Operations for U.S. Pacific Fleet. He has served as 3rd Fleet N2, 7th Fleet Deputy N2, Senior Intelligence Officer for China at the Office of Naval Intelligence and Director of the Navy Asia Pacific Advisory Group. His opinions do not represent those of the U.S. Government, Department of Defense, or Department of the Navy.

1. Michael Palmer, Command at Sea: Naval Command and Control since the Sixteenth Century, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007, p. 255.

2. The full text of King’s memo is found in The Administration of the Navy Department in World War II, Washington, DC: Naval History Division, 1959, as appendix 1.

Featured Image: USS BB 30 “Florida” – April 1919.

Those of us who went to the Coast Guard Academy will recognize the phrase “trained initiative.”