By Chris Nelson

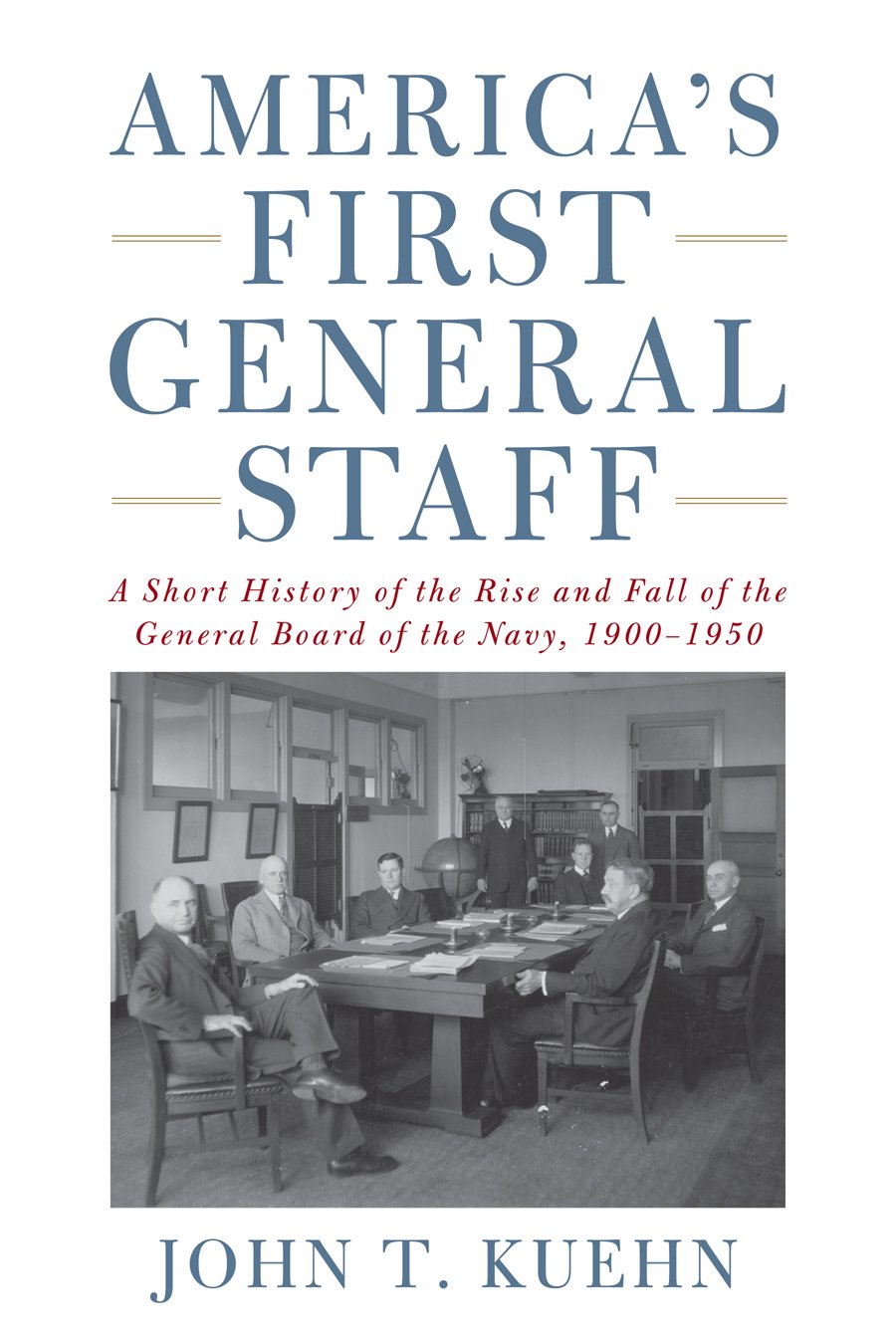

Professor John Kuehn’s new book, America’s First General Staff: A Short History of the Rise and Fall of the General Board of the U.S. Navy, 1900-1950, is a detailed and fascinating look at how the U.S. Navy’s General Board began at the turn of the 20th century and evolved into what would become the core of U.S. naval planning and strategy.

Dr. Kuehn, a military history professor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, joins us to discuss his new book.

Christopher Nelson: Professor Kuehn, your book, Agents of Innovation, was also about the Navy’s General Staff. How is this book different?

John Kuehn: The difference is time period and focus.  Agents (my nickname for it) covered naval innovation in the interwar period, 1919 to 1937, as affected by the Board, by War Plan Orange, and by the Washington and other naval conferences. The coverage of that innovation was episodic, not comprehensive, and the focus was on three case studies – battleship modernization, naval aviation, and mobile, at sea, basing. America’s First General Staff (AFGS) instead looks at the complete “life” of a relativity small organization that had a big impact at the strategic and policy levels. In short, AFGS gives another 30 years of the story while filling in some gaps for the 1920s and 1930s, as well as explaining how the organization came about.

Agents (my nickname for it) covered naval innovation in the interwar period, 1919 to 1937, as affected by the Board, by War Plan Orange, and by the Washington and other naval conferences. The coverage of that innovation was episodic, not comprehensive, and the focus was on three case studies – battleship modernization, naval aviation, and mobile, at sea, basing. America’s First General Staff (AFGS) instead looks at the complete “life” of a relativity small organization that had a big impact at the strategic and policy levels. In short, AFGS gives another 30 years of the story while filling in some gaps for the 1920s and 1930s, as well as explaining how the organization came about.

CN: For readers who might have little or no understanding of the Navy’s General Board, could you briefly describe what it was and its purpose?

JK: The General Board was a small group, about the size of a war college seminar, or smaller—generally from six to 12 officers, mostly captains and admirals, although they had non-member junior officers sometimes assigned and who were mentored by the senior ones. It was somewhat like the recently disestablished CNO strategic studies group (CNO-SSG)—but smaller and more independent. It was created in 1900 to serve as an “experiment” or proof of concept for the Secretary of the Navy for a naval general staff, which the naval reformers like A.T. Mahan, Stephen Luce, and Henry Taylor had been agitating for. As a naval general staff it did all those things one would expect a naval general staff to do, and in 1902 part of it went to sea! In other words, its primary job was contingency planning for crises and war—war planning—but it slowly extended its influence into all facets of the Navy, especially mobilization planning and fleet design. But it was primarily a shore and a peacetime staff, which was when it did its best work.

After 1909 it was the “balance wheel” or umpire for all ship designs in terms of what warships were being designed to do in war (or as deterrents in peace). After 1916 its war planning function migrated to CNO. Some bureaus kept forwarding their war plans inputs to the Board for years afterwards and CNO always had war planners at key hearings. I argue in the book that in many ways CNO became the operational naval general staff, while the small General Board, never more than 12 members or so, remained a sort of strategic and policy level executive body.

CN: A primary responsibility of the board was to produce reports on numerous topics. What were some of those reports? How valuable were they?

JK: They are known as General Board studies –their primary written product–but referred to by the Board as “serials.” I explain them rather well in Agents in my chapter on the General Board Process (chapter 3). As you can see Agents and AFGS really are a set, they complement each other.

The serials were extremely valuable because they went to the Secretary of the Navy, who had no SECDEF over him most of the time of the Board’s life, and set Navy policy on everything from uniforms to disarmament agreements to priority of naval construction. Especially critical for the historian are the 420 series “policy” serials that cover general naval policy (and strategy) as well as building policy and priority. These are my favorites. Reading them is like reading from a book of prophecy—they predicted so many things that eventually happened. Another great series are the arms limitations serials, the 438 series, that informed the Secretary of the Navy of the Board’s advice and recommendations about upcoming arms conferences at Geneva or London after Washington in 1922. 449 series are the ones on naval aviation. Anything with naval aviation is entertaining because of all the characters—Moffett, Turner, King, Mitscher, Towers, Mustin—that were involved with the hearings and the writing. Those guys had color in their language. The studies folders don’t just include the various drafts of the serials, but also the background material, so you get to read handwritten notes by Moffett for example. What an amazing organizational leader.

Most of the studies had an associated hearing that went with them. This is all indexed, by the General Board, and now on microfilm (or digitized by me). I haven’t digitized or organized everything yet, though!

CN: How did the board support the CNO through the long and valuable “Fleet Problem” series that ran from the early 1920s to the beginning of WWII?

JK: CNO, the Naval War College, and the Board worked hand-in-glove for most of the interwar period, even after CNO was no longer a member in 1932. Ironically, I think Pratt separated himself from the Board to give it more independence, not less, but it worked the other way, giving subsequent CNOs more power over time until King arrived and swept all the organizations of the Navy before him as he unified command as CNO/COMINCH. However, when given the chance to get rid of the Board, King proved instrumental in ensuring Nimitz did not abolish it, and he tried, believe me, after the war. Nimitz was being advised by wartime guys who valued war experience over the more careful methodical processes of the Board, guys like Ramsay and especially Mick Carney (Halsey’s chief of staff at Leyte Gulf).

Here is how it worked circa 1928. The war college would war game “strategic problems” at the college and then “hot wash” (AAR) these games. The results would go, as Al Nofi discusses in his great study (To Train the Fleet for War, Naval War College Press), to the CNO war plans division and the Fleet (i.e. the Fleet Commander and staff, CINCUS Fleet) and the agenda for the fleet problems for the annual exercise established. Not all the NWC stuff made it to the fleet problems, and sometimes the fleet problems dealt with stuff not gamed the previous year at NWC, but it was the interaction and feedback loops that were key—naval messages and talking back and forth between an informed officer corps. The General Board received inputs and feedback from these games and exercises, from the Fleet, from the war plans division of OpNav, and from the NWC in constructing its 420 -2 building priorities and warship designs, as well as its positions for the naval conferences. They would turn what was going on into policy and force structure.

This is an oversimplification, but the process here was iterative, ongoing, and they managed to work through, either in NWC, in the hearings of the Board, and in the fleet during the annual exercises, most of the dynamics for most of the problems faced by the Navy in World War II. The closest thing to it outside the U.S. was the stuff being done by Hans von Seeckt and his small officer corps with the Reichswehr in the Weimar Republic.

I do not say these U.S. Navy entities necessarily “solved” those problems, but institutionally the Navy officer corps understood the framework of its problems as well, or better, than any other naval officer corps on the eve of war.

CN: How do the Navy’s bureaus and aide system fit into this story? Did they complement or cause friction?

JK: The Bureaus quite naturally opposed the Board’s creation and its influence, generally, unless they were led by a reformer like Henry Taylor or Bradley Fiske, then they worked with the Board. Fiske helped created the Aide system, which for your readers was a system from 1909 onward that created super-Bureau Chiefs, if you will, who handled material, operations, etc. They were aides not just to the Secretary of the Navy, but to the Board. But the aides were all part of the General Board system. As were some of the Bureaus…whose chiefs would sometimes be assigned on a temporary basis to the Board. Over time the bureaus collaborated effectively with the Board—especially the Bureaus of Aeronautics and Construction & Repair—which they saw as something of a reasonable counterweight to the increasingly powerful OpNav (CNO) staff. However, World War II changed all of that and both the bureaus and the Board lost power and influence that went to OpNav during that war. I explain all of that in this book.

As for the aide system, it went away with CNO’s creation in 1915 and until 1932 the Board and CNO collaborated effectively because CNO was an ex officio member of the board, although often not its chairman. The head of the Naval War College, the head of the Office of Naval Intelligence, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps were also on the Board during that time as ex officio members. The chairman was usually the senior retired Navy admiral still on active duty—but would always revert to rear admiral rank when no longer in a four star billet. Again, World War II changed much of this. I like the pre-World War II system and that is why I put the Board in civilian clothes as the picture of the dust jacket of my book. I think if not in service billet or global combatant or theater command, all flag officers should revert to two stars. That system worked for over 180 years.

The other organization that worked hand-in-glove with the Board, from 1900 until the Pratt decision in 1932 to pull the ex officio members off of the Board, was the Naval War College. AFGS offers much more discussion of this key decision and its long-term impact than does Agents. More to follow.

CN: In your book, you describe in detail some of the more outspoken and influential naval officers responsible for the success of the General Board. In your mind, who were the top three or four officers who, in different ways, shaped these organizations?

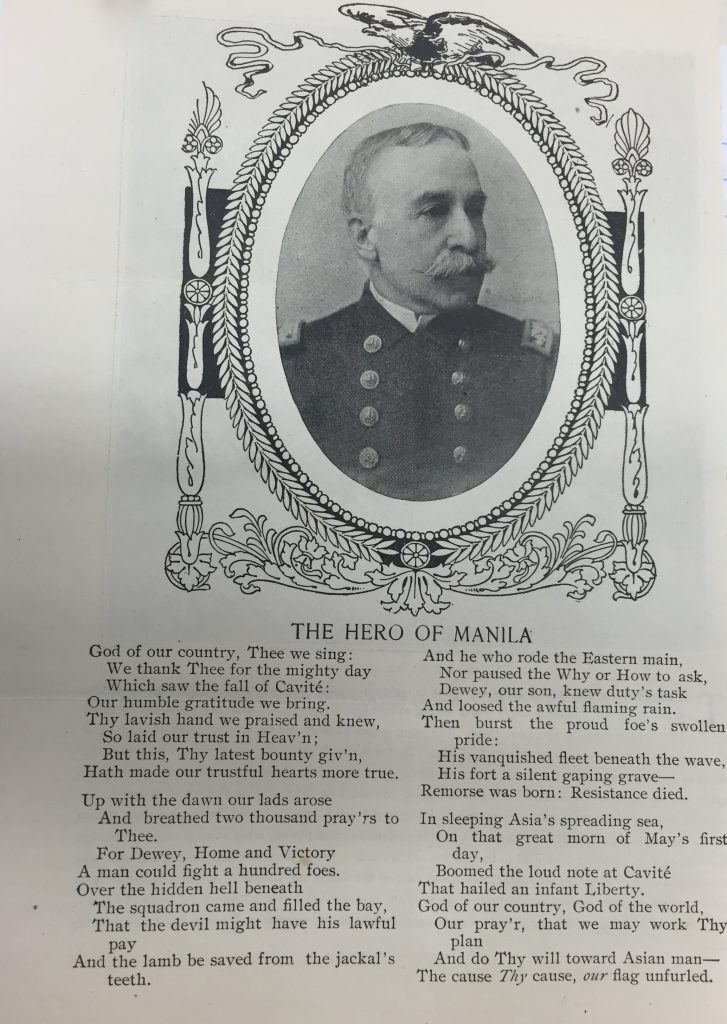

JK: I have mentioned several of them already—Henry Taylor, and of course the one and only President of the Board, George Dewey. But Taylor was Dewey’s right-hand man and I do not think the Board would have come to fruition without him, at least in the way it did. Even so, as I argue, Dewey ensured its long-term success by simply living so long and also influencing things with a very light touch. Dewey was a master of organizational leadership using what the Army calls “mission command”—but Dewey’s approach was more German, he really gave general guidance and left his subordinates, like Fiske, room to make decisions. Dewey provided what today we call “top cover.” As Admiral of the Fleet, (the only one in American history), Dewey could do that.

I mentioned Bradley Fiske, he was another key member of the Board, although he came to see it as not Prusso-German enough to be to effectively fight the Germans, who he and Dewey saw as the main enemy. Fiske engineered the creation of CNO to get a “real” naval general staff, but was frustrated in becoming its head, but Fiske played his role. Instead the cagey, and often maligned Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels made the shrewd pick of William Benson, already serving on the General Board, as first CNO. Fiske was a fascinating, brilliant officer, but definitely one with militarist tendencies.

In the interwar period, the most important guys were Hilary Jones, Bill Pratt, and Mark Bristol, all of them exceptional, and even visionary in the case of Pratt. I am revisionist on the score of Jones, who many historians see as a fossil. I found him a model for the naval diplomat/strategist and just the guy the Board needed during the lean years of the 1920s, a lot more progressive than folks think. Noted naval historian William Braisted, by the way, agrees with this position.

Finally, in the years after World War II John Towers

almost singlehandedly saved the General Board, bringing it back to very much the size and composition it had, with the Marines as members, similar to Henry Taylor’s original design and then the one in place from 1915 on. However, the NWC president remained off the Board, a key mistake I think. But once Towers left I think the Board’s days were numbered because of unification and the 1947 National Security Act. It is fitting though that the Board began with the most senior Admiral in the Navy and nearly ended with the most senior (by lineal number on active duty). However, the so-called revolt of the admirals seems to have hastened the demise of the Board as all the folks who knew its value departed the scene, especially James Forrestal, CNO Admiral Louis Denfield—fired by Forrestal’s replacement Louis Johnson—and Navy Secretary John Sullivan. They were all supporters of the Board and its value to the Navy.

CN: The General Board took detailed minutes of their meetings. To my knowledge, that’s not something we do today, in the Joint Chiefs’ “Tank” for instance. As a historian how valuable were these minutes? Is it disconcerting that we don’t have these types of records today?

JK: Invaluable, and yes, disconcerting. I was just writing to someone how the General Board seemed to have a sense of its unique historical importance, a sense of itself and the good work it was doing. This spirit came from the historical-mindedness of officers like Taylor, Badger, Dewey, Pratt, Dudley Knox, and Ernest King. See David Kohnen’s book 21st Century Knox for more on this score. The Board kept track of its every meeting in proceedings –written by its most junior member, the secretary of the board (usually a LCDR or CDR)–for its entire organizational life. Some secretaries of the Board include Thomas Kinkaid and Robert Ghormley. Being secretary for the Board was almost a deep select for admiral. Being on the Board as a junior officer or captain was a positive career move in today’s language. These “shore billets” attracted the Navy’s best and brightest.

The Board was also practical in terms of understanding what had happened, and how things happened. Anyone could go back and read the transcripts. As for the transcribed hearings, they came later in 1917. These changes –the complete transcription of the hearings with a stenographer/court recorder–were made as a result of the war in 1917, by Admiral Charles Badger, a guy who gets way too little credit. When the Board was disestablished its last chairman made sure the records were not destroyed and turned over all the files to Dudley Knox’s organizational baby, the Naval Historical Center (now Naval History and Heritage Command, NHHC). Most of them are now part of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), in downtown DC, but some records are still with the NHHC, for example Arleigh Burke’s General Board “notebook” from his time on the board during the Towers chairmanship.

CN: How were these naval officers able to remain collegial when they sat on the board? Strong personalities and competing visions of what the Navy should build and the adversaries we should prepare to fight are rife through our history. Many disagreed. How did the board handle this?

JK: It is a fascinating lesson for today. One really must read the hearing transcripts at length to get a feel for how well they got on, even during contentious testimony like that of Billy Mitchell in 1919. That is why I included extensive passages of the banter in Agents, but I did not really have the room to do so in AFGS…a pity. I have thought about possibly publishing some of the more entertaining hearing transcripts in edited commentary format.

Back to your question—they respected each other and their witnesses, it is that simple. They also knew, with one exception, that what they said would not show up in the newspapers or public debate because the hearings were all classified. Non-attribution if you will. The one exception, of course, was Billy Mitchell, and he was censured by the Secretary of War Newton Baker for doing so! Mitchell lied and told a Congressional Committee that the Board agreed with him that navies were “almost useless” in 1920 during a hearing on aviation.

CN: Looking through your bibliography, besides the meeting minutes, there are plenty of other resources, like naval memoirs/biographies/autobiographies that you used to tell this story. Are there any autobiographies or biographies of 20th century or even 19th-century naval officers that you found particularly fascinating?

JK: John Towers’ biography was fun, a good read, but I disagree with its take on his time on the General Board. However, it is those guys without biographies that I found most fascinating, especially Mark Bristol, who has been written about much of late for his role in commanding the U.S. Black Sea squadron after WW I and then the Asiatic Fleet during the turbulent years of the China Patrol in 1920s warlord China. Taylor, of course, was fascinating and deserves a biography, too. I hope Al Nofi is reading this, he and I agree that many of these guys need a decent biographer. Gerald Wheeler’s biography of Bill Pratt is a gem, USNI should reprint it, and Fiske’s memoir is great, funny even, but one must be careful because sometimes his agenda displaces the actual facts. As for the 19th century, God and Seapower on a new spiritual biography of Mahan by Suzanne Geissler is essential, but for the real flavor readers are directed to the older issues of the Naval Institute Proceedings, now digitized from the 1870s on. It is there they will find the writings of these guys like Luce, Taylor, Chadwick French, etc., in articles and comments.

CN: What was the beginning of the end of the General Board?

JK: The General Board died a slow death. The decline, in retrospect, began with the departure of the CNO, Commandant of the Marine Corps, and President of the Naval War College as ex officio members in 1932. But the decline did not become pronounced until World War II, when the General Board found itself eclipsed by OpNav and the JCS strategic organizations under General Marshall. World War II was a key event that changed the culture and organizational focus and norms of the Navy, it midwifed the Navy we have today—forward deployed, primarily used for power projection, with an always high optempo. The Navy the General Board served for most of its life was not the kind of navy the U.S. had after 1941. The revolt of the admirals, creation of DOD, and ascendancy of what I call “OpNav Culture” were the final forcing functions that saw the Board die its quiet death in 1950, its passing overshadowed by the Korean and Cold Wars.

Its staying power in the face of all that is remarkable. Admiral King is the key, he could have easily have gotten Frank Knox or James Forrestal to abolish the Board but did not. I sometimes wonder if King considered perhaps retiring and then assuming presidency of the Board himself instead of Towers, that way he could continue to wield some of the enormous power he had held after stepping down as CNO and COMINCH. Perhaps though, that role did not have power enough for a man like King!

CN: Professor, this has been great. Thank you.

JK: It has been my pleasure and thank you for allowing me to discuss my scholarship.

Commander (retired) John T. Kuehn is a professor of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. A former naval aviator, he is the author of Agents of Innovation (Naval Institute Press, 2008) and the coauthor, with D. M. Giangreco, of Eyewitness Pacific Theater (Sterling, 2008). He has published numerous articles and editorials and was awarded a Moncado Prize from the Society for Military History in 2011. He has also published A Military History of Japan (Praeger 2014) and Napoleonic Warfare: The Operational Art of the Great Campaigns (Praeger 2015). His next published work will be a chapter in an anthology on service cultures. Dr. Kuehn’s chapter is on the U.S. Navy cultural transformations between 1941 and the present.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson is a regular contributor to CIMSEC and is currently stationed at the U.S. Pacific Fleet headquarters. The views here are his own.

Featured Image: Meeting at the Navy Department, Washington, D.C., 1932. Those seated are (left to right): Rear Admiral Mark L. Bristol; Rear Admiral Charles B. McVay, Jr.; Captain John W. Greenslade; Commander Theodore S. Wilkinson (Secretary); Rear Admiral Jehu V. Chase; and Captain Cyrus W. Cole. Standing are (left to right): Lieutenant Colonel Lewis C. Lucas, USMC(Retired); and Commander Edgar M. Williams. Number over the door in left center is “2748”, indicating that this office was located on the second deck of the “Main Navy” Building. Note portrait of Admiral of the Navy George Dewey, first President of the General Board, on the wall to the left. (U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.)