By Trevor Phillips-Levine, Dylan Phillips-Levine, and Walker Mills

As the German U-boat prepared to ascend to periscope depth, the crew was unaware that a Grumman G-44 Widgeon Coastal Patrol aircraft had been shadowing it for the last three hours. It was the summer of 1942 and the Eastern Seaboard of the United States was a battleground. U-boats were stalking and sinking merchant ships transporting vital war materials and U.S. Navy and Coast Guard assets were stretched thin. The two pilots of the Coastal Patrol aircraft, armed with two depth charges, maneuvered into an employment position and dropped their charges.

Notably, the crew and aircraft were not military, but instead part of a civilian volunteer organization. By August 1943, U.S. military assets could adequately cover defense requirements and the Coastal Patrol stood down. While U-boat records do not attribute any U-boat losses to Coastal Patrol sorties, these civilian fliers were very successful in forcing U-boats to submerge, greatly curtailing their ability to attack and communicate.

As strategic competition heats up between the U.S. and China, the U.S. is seemingly at a disadvantage when compared to China’s ability to mobilize and militarize commercial enterprises with plausible deniability like its vast distant-water fishing fleet. In order to adequately counter China’s aggressive overseas fishing fleet, the U.S. should rely on a combination of technology and global volunteerism. Just as Coastal Patrol helped plug a capability gap and hobble German U-boat operations, the U.S. can help counter malign Chinese fishing activities by supporting allies with cheap surveillance networks and capitalizing on environmental volunteerism.

Commercial Fishing Fleets

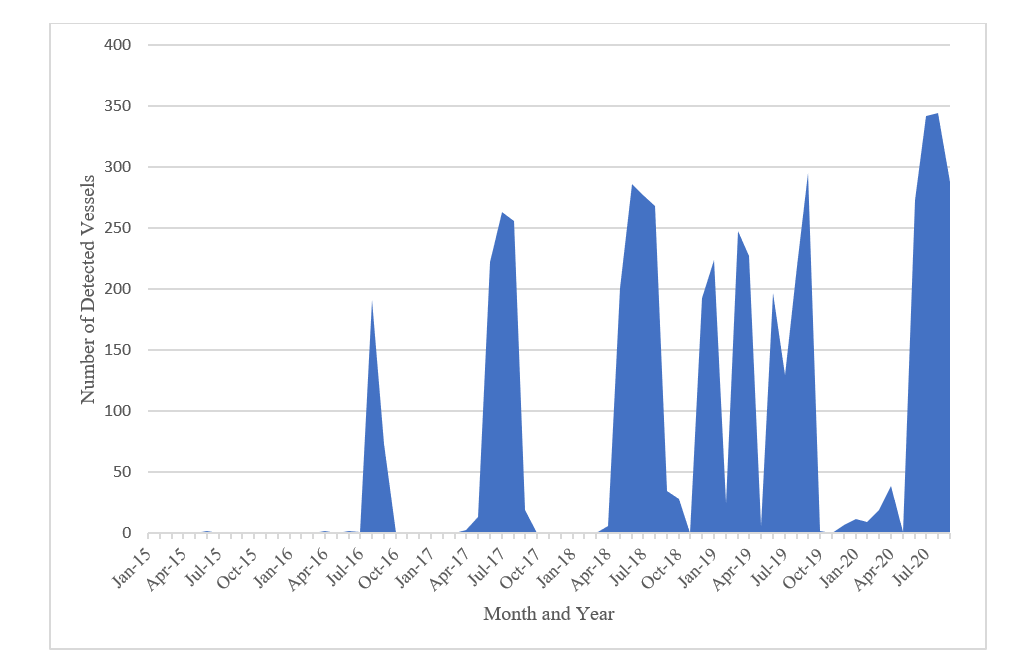

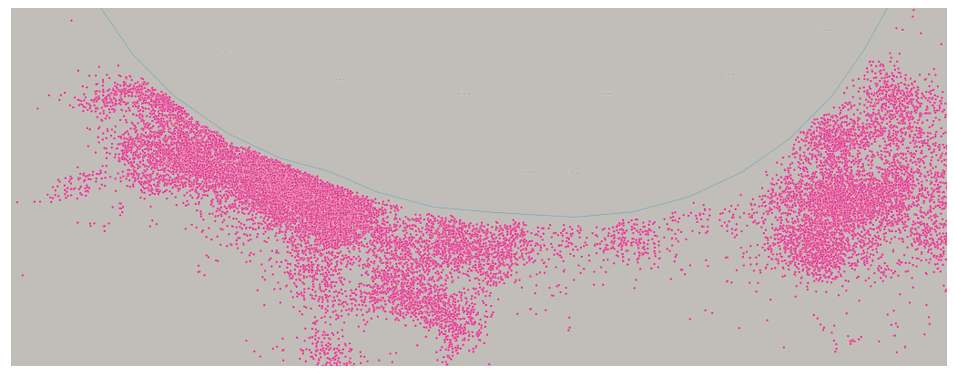

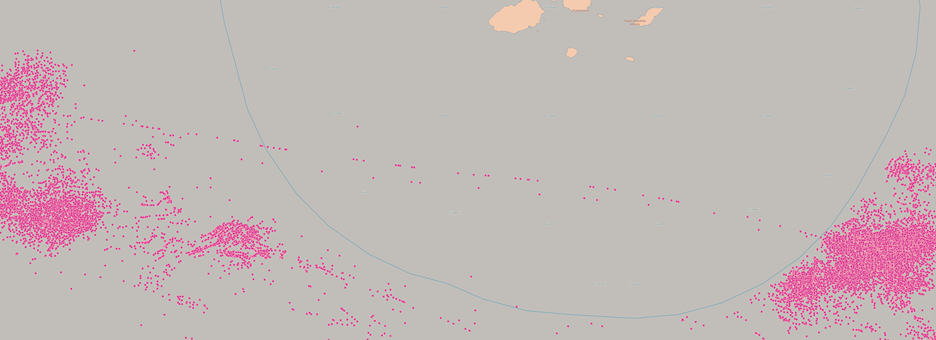

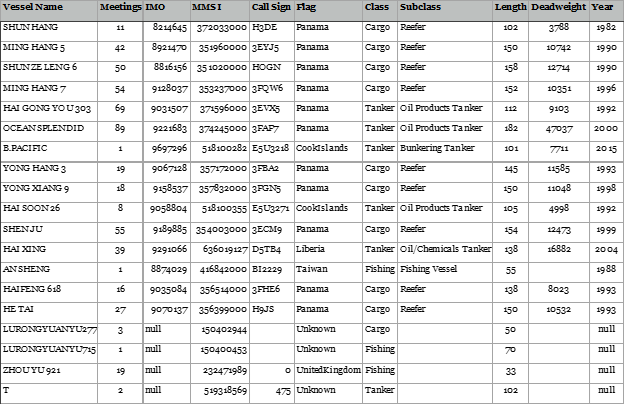

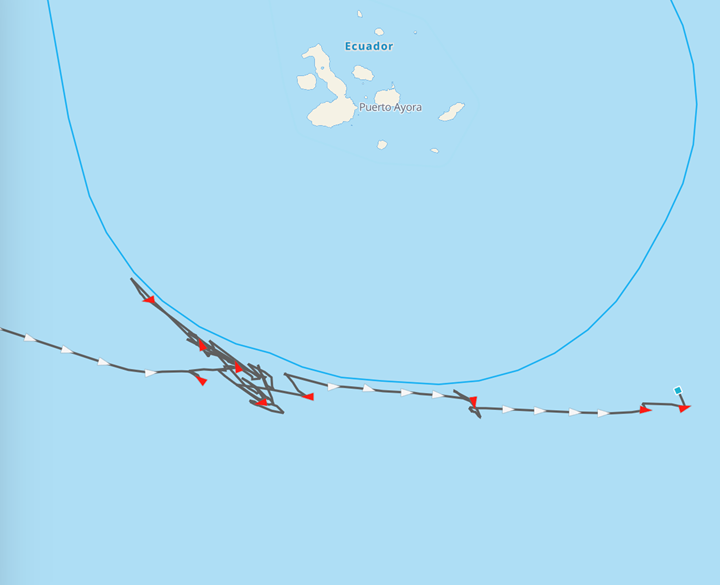

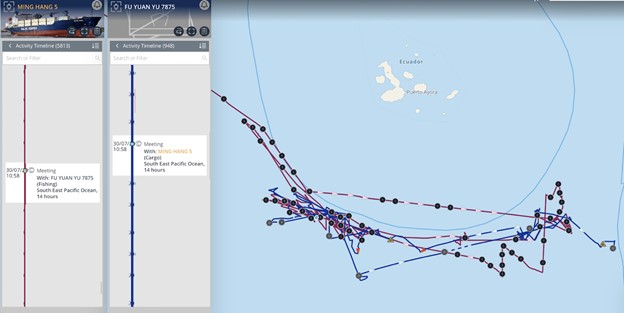

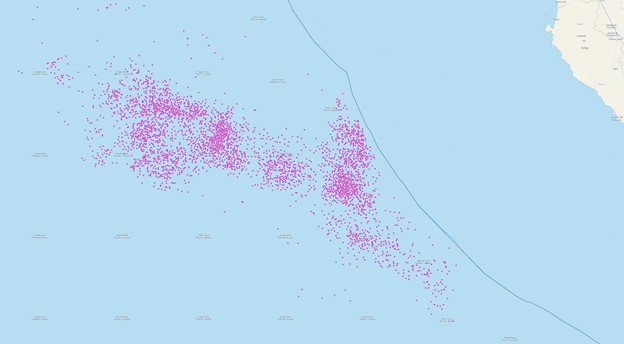

Recently, Ecuador raised alarm over the presence of 340 fishing vessels congregating outside the protected waters of the Galapagos Islands. Almost all of them were part of the Chinese distant-water fishing fleet. The situation escalated when many vessels within the fleet turned off their satellite transponders to avoid being monitored and, presumably, the scrutiny of Ecuadorian authorities. Ecuador responded by sending surveillance assets to monitor the flotilla. Unable to adequately monitor such a large flotilla with their own assets, Ecuador requested assistance and intelligence sharing from Colombia and Peru.

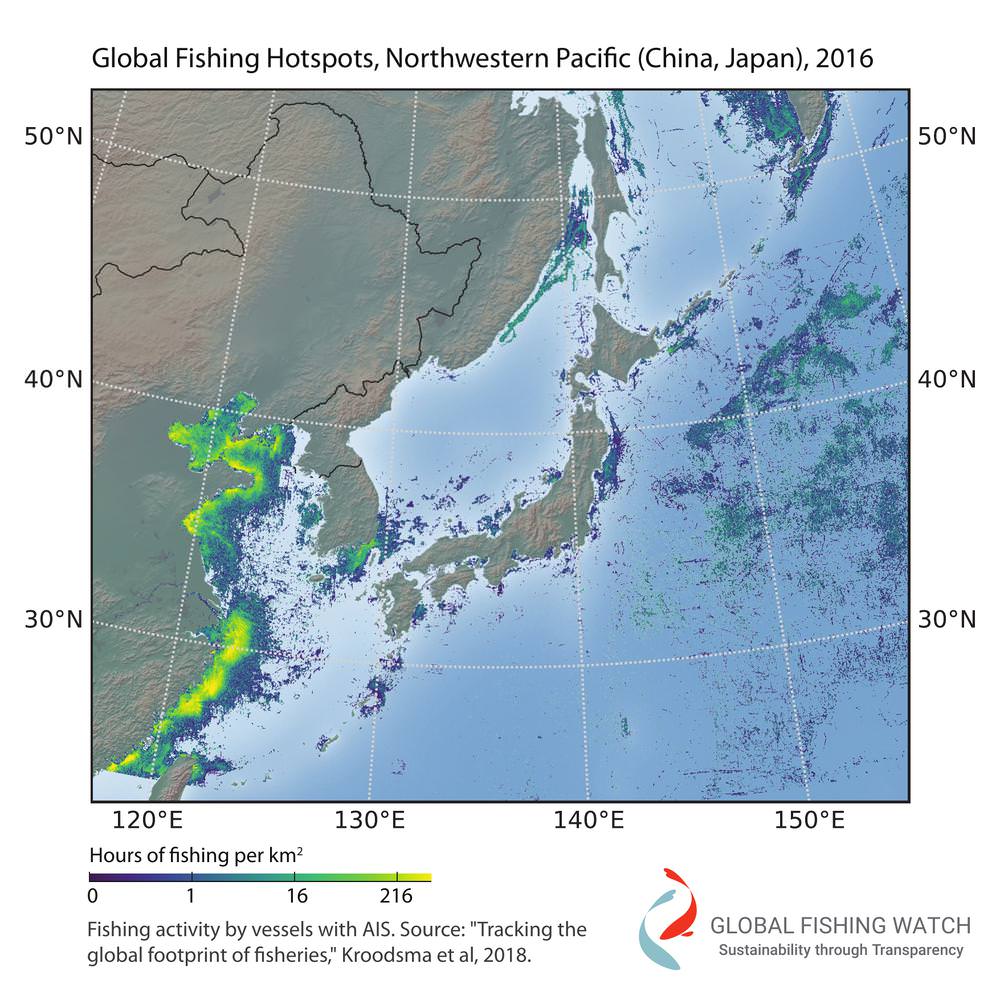

Ecuador had reason to worry. In 2017 Ecuadorian authorities seized a Chinese fishing vessel with over 300 tons of illegally fished sharks (some endangered) comprising of roughly 6,600 animals. When Chinese fishermen act aggressively and illegally, it is likely that they have at least some form of tacit government approval considering the authoritarian nature of the Chinese regime. Though Beijing denies irresponsible fishing practices, the data suggests otherwise. China has the largest distant-water fishing fleet in the world at over 17,000 vessels. The fishing fleet also receives government subsidies that incentivize private companies and ship owners to expand their fleet and range. China has militarized part of its fishing fleet as part of the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia, which can be employed as a paramilitary force in altercations with other national fishing fleets and law enforcement vessels. Beijing uses the Maritime Militia as part of a coordinated effort to challenge maritime sovereignty and conduct surveillance of its neighbors within the “gray zone” where triggered responses are unlikely to rise to the level of direct military intervention. Retired U.S. Navy Admiral James Stavridis has argued that China’s distant-water fishing fleet is part of a strategy of “hybrid warfare.” Through “coercive maritime diplomacy,” Chinese fishing vessels assist Beijing in asserting claims in contested waters by using sheer numbers to overwhelm another nation’s ability to enforce their sovereignty. These vessels have been used in disputes against claimants in the South China Sea and Japan. As the immediate peripheral waters surrounding China were depleted of marine life and its growing population’s demand for sources of protein grew, its fleets moved outward.

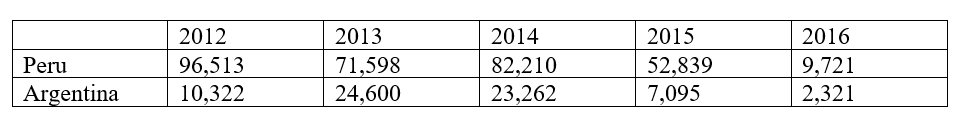

This outward expansion is being felt globally. On August 8th, 2020, just days after a Chinese fleet appeared off the Galapagos Islands, a pair of Chinese fishing trawlers (Guo Ji 826 and Guo Ji 866) were arrested by Gabonese authorities with over one metric ton of illegally fished fins and rays off the west coast of Africa. In 2016, Argentina sank a Chinese vessel illegally fishing within its economic exclusive zone (EEZ). Global Fishing Watch, using satellite data, showed systemic illegal fishing by Chinese fishing fleets in North Korean waters between 2017 and 2018. Some 1,600 vessels are estimated to have harvested over 160,000 tons of squid from North Korean waters. Like the fleet off the Galapagos, these aggressive fishing fleets usually operated in the “dark” with turned-off transponders, making it more difficult for local authorities to respond. Overfishing in North Korean waters drove scores of fishermen to more dangerous seas. Many were unable to compete with the larger Chinese boats and may have been harassed. These aggressive fishing practices have been linked to over 600 “ghost ships,” vessels that have washed ashore on Japan’s shorelines with the crew missing and sometimes with human remains. Researchers have called it “the largest known case of illegal fishing perpetrated by vessels originating from one country operating in another nation’s waters.”

In many cases, it appears Chinese fishing fleets target waters of nations that lack robust maritime law enforcement capability. A 2015 Greenpeace report monitoring illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing off shorelines in Africa found that Chinese fishing activities “were taking advantage of weak enforcement and supervision by local and Chinese authorities to the detriment of local fisherman and the environment.’”

In both his recent comments and the new US Coast Guard Illegal, Unregulated, and Unreported Fishing Strategic Outlook, Commandant of the Coast Guard Admiral Karl Schultz called IUU fishing a “national security threat.” He said also “[It’s] bigger than catching a few boats with illegal tuna. This is really about the systemic violating of sovereign nation rights. IUU fishing could lead to armed conflict in the future over resources instead of ideological reasons. Separately, the head of US Southern Command, Admiral Craig Faller, called illegal fishing one of the top threats in the Western Hemisphere and noted that China is the most egregious violator. He added, “This [threat] has us focused with a sense of urgency day in and day out.”

Tapping into Environmentalism and Non-Governmental Organizations

During President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address in January 1961, he delivered his famous charge:

“And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.”

With the Cold War in full swing, Kennedy realized that a whole-of-nation approach was required to effectively counter Soviet expansionism. He also recognized that strength came through alliances and engagement. Kennedy looked to mobilize patriotic young Americans to serve their country in engagement activities within the Peace Corps.

Similarly, young people today are motivated to contribute to global causes with environmentalism being one of the largest (if not the largest) global movements. Numerous environmental and humanitarian organizations, many staffed by volunteers, operate throughout the world. In countering aggressive Chinese fishing practices, the U.S., smaller nations, and environmentalists find themselves on common ground. Couched in environmental rhetoric, governments can enlist the help of volunteers and NGOs to help defend their fisheries and bolster capacity.

Many victims of China’s distant-water fleet lack robust enforcement capability on their own and would benefit from outside support. In this regard, maritime-focused NGOs can offer immense help. The environmental direct-action group, Sea Shepherd, operates a small fleet of ships committed to protecting the world’s oceans. Made famous by the show “Whale Wars,” the Sea Shepherd organization has operated since 1977. The arrest of two Chinese trawlers, Guo Ji 826 and 866, were actually made by Gabonese authorities embarked upon Sea Shepherd vessels. In January 2020, Sea Shepherd signed an agreement with the Attorney General of Ecuador to bolster its enforcement capability against illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. Greenpeace has also been monitoring and reporting on IUU activities with their own fleet of vessels crewed by volunteers.

Volunteer organizations have the ability to make immediate impacts in a significantly shorter time period, at a fraction of the cost, than it would take to stand-up and equip instruments of a nation’s maritime forces for global enforcement duties. Organizations like Sea Shepherd and Greenpeace are crewed by volunteers and operate on donations from private donors spanning the globe. Maritime experts have argued for greater interagency and international cooperation in combating illegal and unregulated fishing before. Similar to the role of Coastal Patrol during WWII, their primary function would be to contribute to regional maritime domain awareness.

Environmental groups have, at times, been at odds with the policies of governments, including the US. In 2013, U.S. courts labeled some of Sea Shepherd’s activities against Japanese whaling vessels as piracy. These activities included aggressive maneuvering, ramming, and throwing bottles filled with noxious liquids. Despite the controversy surrounding some activities that direct-action environmentalists may take, their independence and credibility make them ideal candidates for contributing to a larger network. Additionally, using international maritime law has proven successful in taming some of the more aggressive tactics utilized by direct-action NGOs.

All told, Coastal Patrol volunteers were responsible for 86,685 sorties, spotted and reported 91 merchant vessels and 363 survivors in distress; reported positions of 173 located U-boats, and dropped 82 munitions on 57 U-boats. Today, Coastal Patrol lives on as a U.S. national organization called the Civil Air Patrol, an auxiliary of the U.S. Air Force, and performs missions that include search and rescue, airlift, and aerial surveillance assistance for drug enforcement missions. While not an NGO, the Coastal Patrol program arose as a way to alleviate wartime stress on a nation not yet on a full war footing, and demonstrated the significant and immediate strategic effects a volunteer organization can have in furthering a country’s objectives. The U.S. would be wise to find similar ways to leverage the international desire to protect environments.

It’s Really About Surveillance

“China is OK with its fleets overfishing and engaging in rapacious activities, but it doesn’t like the bad publicity of outright illegality,” stated Greg Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. China aspires to become a global power and one of immense influence. Culturally, shame carries emotional responses of great import to the Chinese people. The result is that Beijing will go to great lengths to save face. As such, countering Chinese malign activities requires spotlighting and documenting such activities through maritime surveillance, at least in the near term, and in waters beyond what it considers its own.

Chinese malign activities are well-documented in the waters of the South and East China Seas, but with respect to fishing the Chinese are even more overt and attempt to bully neighbors into capitulation through numbers and regular incursions. For example, the Chinese Coast Guard and Maritime Militia routinely back up Chinese fishing vessels in confrontations. In one instance a Chinese fishing vessel rammed and sunk a pursuing South Korean Coast Guard vessel in 2016 before fleeing. These behaviors require more robust responses, but for now, enabling Latin American countries with surveillance and enforcement capabilities will help counter Chinese expansion. Through robust surveillance, enforcement assets can be more efficiently deployed to areas that contain violators.

With countries that have closer relationships with the U.S., direct support is possible through law enforcement agencies, the U.S. Coast Guard, and military cooperation. These include providing assets and intelligence sharing. Such assets should include autonomous unmanned systems that allow for broad area surveillance. DARPA’s Ocean of Things concept is very aptly suited to monitor large expanses of ocean for relatively low costs and is similar in function to China’s Ocean-E surveillance network that has been deployed in the South China Sea. While both systems can be loaded with environmental sensor payloads, the ability of the sensor networks to track airborne, surface, and submerged vessels has immense intelligence, law enforcement, and military value.

In Latin America, as it is in other places in the world, the U.S. must walk a more delicate line since interventionist policies of the past are still raw in some collective memories. As Lisa McKinnon Munde aptly pointed out in her essay in War on the Rocks, the U.S. should not seek to lead, but rather enable and allow host countries to “set the pace” of cooperation and its scope. When aiding countries wary of U.S. help, the U.S. should offer support through NGOs that have global footprints.

Some Latin American countries are justifiably wary of U.S. involvement in their affairs and may wish to not participate in interagency task forces headed by the U.S. and operating within their respective EEZs. Governments wary of direct partnerships with the U.S. may more freely accept offers of aid from independent NGOs in enforcing their maritime sovereignty. Leveraging NGOs in these cases may allow for more palatable relationships in the form of indirect partnerships or cooperation in countering Chinese IUU fishing activities. In this way, more assets can be deployed in a concerted effort to monitor, report, and enforce in response to malign fishing activities by Chinese-sponsored enterprises.

Conclusion

An integrated approach that leverages regional governmental cooperation supplemented by U.S. maritime surveillance resources and NGOs is the only approach that can effectively combat aggressive illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing by Chinese distant-water fleets. Individually, local governments simply do not have the resources to effectively police their massive fisheries by themselves even as they seek to bolster their presence with new, patrol-minded vessels. However, the U.S. in combination with environmental NGOs can help fill the gap.

It is not just about protecting the environment – overfishing and expansion into other countries’ EEZs have a destabilizing impact and could lead to armed conflict in the future over resources. U.S. Coast Guard Commander Kate Higgins-Bloom noted that “The odds that a squabble over fishing rights could turn into a major armed conflict are rising.” It has happened before, and illegal fishing is an unmistakable part of great power competition Because this problem is truly global and affects the waters of many nations, it will require the concerted effort of nations and regional cooperation.

Congress has already asked the U.S. Navy to help fight illegal fishing. With U.S. support, NGOs can expand operations and provide greater monitoring and coverage capabilities. With external support enabling increased maritime domain awareness, smaller navies can more effectively use their assets for interdiction and enforcement. As was the case with the Coastal Patrol, even minor surveillance contributions by civilian groups can significantly unburden naval and law enforcement vessels. NGOs benefit from increased support and promotion of their mission. Meanwhile, the U.S. and humanity writ large can benefit by countering malign Chinese expansion, promoting greater international cooperation, and increased awareness of what is occurring in the world’s oceans.

Trevor Phillips-Levine is a lieutenant commander in the United States Navy. He has flown the F/A-18 Super Hornet in support of Operations New Dawn and Enduring Freedom and is currently serving as a department head in VFA-2. He was previously assigned to Naval Special Warfare as a JTAC and fires support officer in support of combat operations in Operation Inherent Resolve.

Dylan Phillips-Levine is a lieutenant commander in the United States Navy. He has flown the T-6B “Texan II” as an instructor and the MH-60R “Seahawk” in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and 4th Fleet in counternarcotics operations. He is currently serving as an instructor in the T-34C-1 Turbo-Mentor as an exchange instructor pilot with the Argentine Navy.

Walker D. Mills is a captain in the Marines. An infantry officer, he is currently serving as an exchange instructor at the Colombian naval academy.

These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the views of any U.S. government department or agency.

Featured Image: Chinese fishing boat Bo Yuan 1 (Photo via Pierre Gleizes/Greenpeace)