By Christopher Nelson

The U.S. Naval Institute’s popular and well-reviewed 21st Century Foundation series continues to grow. This past May, Dr. David Kohnen added to the list with his 21st Century Knox: Influence, Sea Power, and History for the Modern Era.

In a review published on CIMSEC back in August, Captain Dale Rielage, USN, said that “Knox offers an example of how an officer with ideas and the willingness to challenge the status quo can have a profound influence on the U.S. Navy.” To learn more about Commodore Knox, and how he challenged naval thinking, I talked with Dr. Kohnen about his new book.

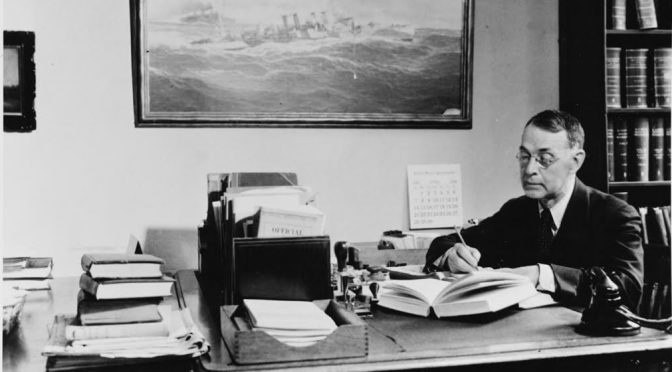

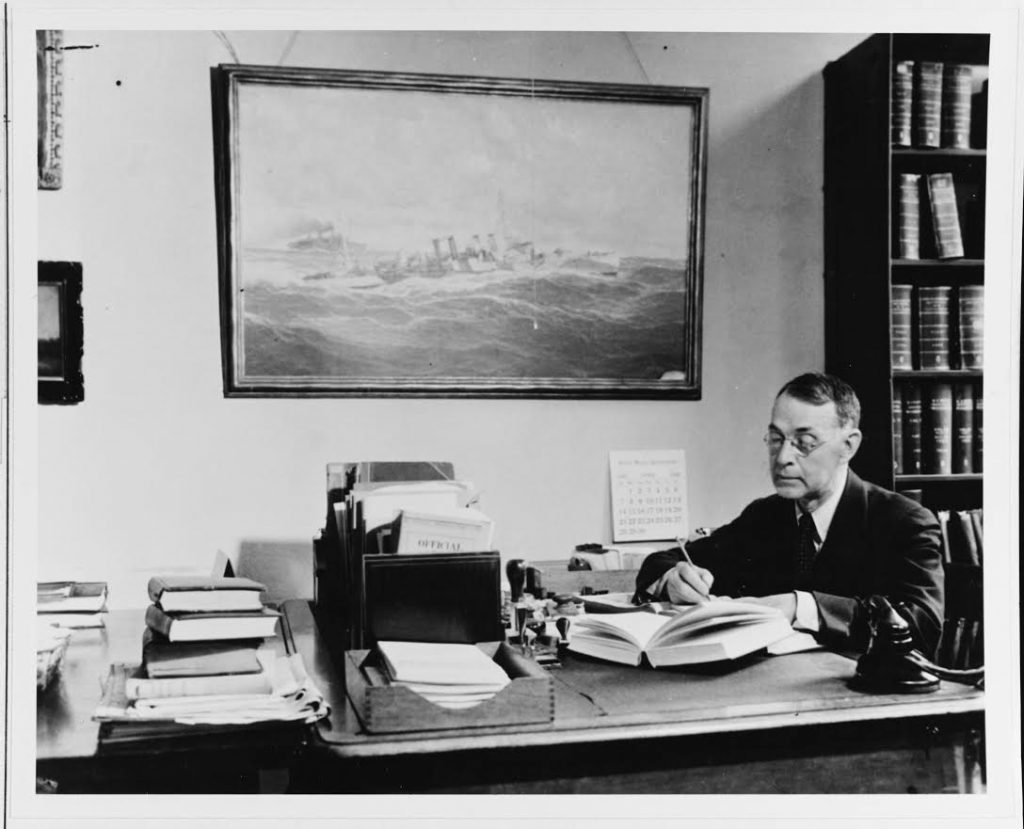

Finally, I am excited to tell you that Dr. Kohnen has provided us with pictures of Commodore Knox and Admirals King and Sims that have never been published. They are published here for the first time.

Professor Kohnen, welcome. Thanks for taking the time to talk about your new book. So, to start, why did you want to write a book about Knox?

Chris, thank you, I greatly appreciate this opportunity to discuss Commodore Dudley W. Knox. Indeed, I firmly believe that Knox stands among the most significant naval thinkers in American history. His ideas truly resonate, as the themes he addressed in his historical work during the first fifty years of the twentieth century informed the development of the U.S. Navy “second to none.” Through his close personal associations with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, Knox became one of the key architects in designing the foundations of U.S. Navy professional military education, in understanding American naval history and traditions, and in advancing the idea of employing the U.S. Navy as an international peacemaker. Knox remains one of the most important figures in understanding American concepts of “sea power” thorough two world wars and into the Cold War era. From my own studies of his life and historical works, I firmly believe that Knox offered strategic observations on concepts of maritime strategy, which transcend into the twenty-first century. I also firmly believe that our Navy should revisit the ideas Knox offers in his writings in order to be better informed of the historical foundations, which have shaped contemporary discussions concerning the future of American sea power and the military policy of the United States.

Knox advised the strategic decision makers who created the U.S. Navy “second to none” and the post-imperial vision of replacing historical empires with multinational alliances under the United Nations. Given his close friendship with Roosevelt and King, I have come to view Knox as a figure perhaps comparable to a Thomas Cromwell, or the fictional consigliore from the Godfather movie, as depicted by the Hollywood actor Robert Duvall. By the way, Knox was also a mentor for Duvall’s father, Commodore William H. Duvall, who served in destroyers in both the Atlantic and Pacific during the Second World War.

I first became aware of Knox as I was working on my dissertation, which focused on Ernest J. King. In the process of writing, I started reconstructing the circle of personalities surrounding King in order to understand the bureaucratic culture and primary group dynamics, which characterized the social character of the U.S. Navy during the first fifty years of the twentieth century. As I am sure you know, the story of Ernest J. King begins during the reconstruction era after the Civil War. He eventually served as Chief of Staff of the Atlantic Fleet during the First World War. Among King’s best friends and closest shipmates was a guy named Dudley Wright Knox. Of course, Knox and King shared a deep interest in history.

Knox had ties with historical figures in American military history. His father was a general officer in the Army, and he had relatives in the service going all the way back to the American Revolutionary period. So Knox is already one of these people who is inclined to think in historical terms.

Then I started mapping out his associations. I’m an intelligence officer in the Navy. So in the same way you do that as an intelligence officer, I began doing that with these historical figures. When you look at the association between King and Knox you start to see other associations. You begin to then see the connection between King, Knox, Nimitz, and then Halsey, Spruance, and the whole gang. So you have this close circle of naval officers who periodically bumped into each other during their careers in the naval service.

Now, in this circle of naval officers, Dudley Knox looms large in the discussion. Knox was a little bit older than the rest of them and he was so sharp minded that people like Ernest King would look to him for advice, perspective, and just good conversation.

Of course, those were the days before distractions like television and the internet. These guys, then, spent their time focusing on their profession – reading the professional literature that should be read for people who want to think about strategy, naval operations, and the maritime dimension. These are books that unfortunately have become obscured in the contemporary context. You think about some of the things that Knox and his contemporaries were reading, people like John Knox Laughton and Spencer Wilkinson. These guys were aware of Corbett long before anyone else was aware of Corbett. They are an interesting group of people. That’s why I started gravitating to Commodore Knox.

Knox, however, was not my main focus in my PhD studies — my focus was Ernest King. But now I had all these “left-overs,” the cutting room types of material after I finished the dissertation on King. And all that extra material was there, so I wrote a paper that I gave at the Oceanic Society of History Conference. On the panel was Claude Berube and B.J. Armstrong. I gave this paper about Knox, and shortly after I finished B.J. slipped me a note. B.J. wrote, “You need to write the book on Knox.” I looked at him and was like, ‘OK, whatever.’ After the conference we went to the pub and B.J. told me about the 21st Century Series and its focus. He convinced me that what I had on Knox would work quite well within the context of the 21st Century Series. It came together relatively quickly because I already knew a lot of things about Knox that simply didn’t exist in the secondary literature — and still doesn’t exist. I’m pretty happy how this little piece came together. It was a great way of bringing Knox back to the 21st century professional naval audience.

And we are not done with Knox. Once I get some other things done, it is my full intention to go back and do something more substantial about Knox. He certainly deserves a focused biography for all the work that he did and the influence that he had, which I highlight in the collection, specifically his associations with Ernest King and Franklin Roosevelt.

I assume it is difficult as an editor to decide what to include in a book and what not to include, particularly if a subject is a prolific writer. How did you go about making those decisions?

That’s an interesting question. So, Commander B.J. Armstrong is the editor of the series, and we’re also good friends. I’m prolific in terms of, well, I like to use a lot of words to say things. And I like to use footnotes and I like to explore every avenue in my analysis. That results in large manuscripts. B.J. was draconian as an editor in executing the sixty-thousand word limit. That really constrained me in terms of what I could do in terms of Knox. We actually cut two essays that I wanted to include just to make sure the pieces fit within the context of the 21st Century Series.

So the balance of putting together Knox’s biographical details, which are not out there in the secondary literature, there’s no real comprehensive biography of Knox available to us – so for the time being, at least, this book is a starting point for a detailed biography, which needs to be written. And if somebody else doesn’t do it I’m going to do it once I get King off my plate. When you think about editing and the choices that you have to make, what I did is I focused on the themes that the CNO is focusing on with his “Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority.” I also considered pieces in light of some of the discussions that are ongoing here at the U.S. Naval War College, contemporary questions of American maritime strategy, naval leadership, ethics (but Knox always talked about the “naval ethos” opposed to ethics), and I think those differences are worthy of discussion. Knox also strongly talked about the importance of understanding the foundations of history in order to frame contemporary discussions about the future. He wrote about these themes. The way he did it was so profoundly unique that Knox remains worthy of consideration in the contemporary context. So, when I assembled these essays I followed those points when selecting the essays in the book.

My favorite essay is actually the last one. It turns out in my mind as the most interesting within the contemporary context. He’s talking about the problem of unification among the services. He’s writing at the time of the revolt of the admirals, which was just erupting. And there all of these problems between the Army and the Navy. The Air Force was newly created; the armed forces security agency; the Central Intelligence Agency; all these new things that came after World War Two. Knox is reeling against the tide as the future was being mapped out. I think Knox was a little bit reluctant to embrace these new ideas because he was still looking at things from the perspective of the past. He understood the problems that came with the bureaucratic changes that happened after the Second World War, which, from Knox’s point of view really didn’t measure up in terms of American ways of war — the American tradition of having a clearly defined civilian command over the military. Knox was worried about a progressive military industrialization of American culture. He wrote about this.

After that last essay, Knox sort of said ‘look, we need to rethink how we are talking about problems of war.’ And he did talk about the importance of how navies are different from armies, and that armies require naval support. Armies are there to conduct operations ashore to achieve an effect ashore. But armies and navies are different, they operate in different environments, and both need airpower to conduct those operations.

So when you follow Knox’s logic he is saying this separation of an air force is a really bad idea. It creates another bureaucracy. As a result you are going to create more flag billets and you are going to see more investment, not less investment, in the military. Knox is reeling against that. Then he does this nice comparison of “Hey if I build an aircraft carrier it is going to last 40 years, you can use it for multiple functions, and use it during peacetime. Rather than if you build a fleet of bombers where its only function is going to be useful if you need to drop a bomb.” Knox did not agree with that sort of approach.

Are there other Knox writings that didn’t make it into the 21st Century Knox but should be read as well?

Dudley Knox was prolific. B.J. and I would go around and around about which essays should go in the book. So like I said earlier, the important part was zeroing in on themes that are immediate interest to the contemporary U.S. Naval professional. That sort of dictated how we were going to put together this little collection. When I compiled the essay that were selected, I focused on the questions of strategy, doctrine, leadership, and of course, the ethos of American naval service. The one thing that I would say that is important in the process of selecting the essays, is that Knox and his associates had this perspective that the naval service has multiple functions. It is not just war. I think Knox would have a problem with contemporary words like “warfighter” because it is too specific. Knox would have reminded us that the Navy is always operational rather if we are at peace or at war. So when you look at his essay titled “Naval Power as a Preserver of Neutrality and Peace,” it is an important essay because he is basically riffing off an essay Teddy Roosevelt published in 1914 titled “Our Navy, Peace Maker.” Now, these themes are important because it is a way of thinking about military service that is different than some of the conversations that we have here in the contemporary era. For example, when you look at their careers, Knox’s generation, coming out of the naval academy at the beginning of the 20th Century, they remained in the naval service for the remainder of their lives. Knox even served in retired status as director of naval history until his death.

When you put together the chronology of some of these guys’ naval careers, and the numbers they spent fighting wars, it only adds up to about eight years. So what are they doing during this other time? So here you have people serving, this idea of service, the ethos of naval service, over a sixty odd year period, and their orientation is not to go find a war but to find ways to avoid a war through sea power. And of course this ties into the theories of Mahan and Luce at the end of the 19th century. Of course, their perspectives reflected an informed understanding of John Knox Laughton’s work, Spencer Wilkinson, Alfred Mahan, and others.

Dudley Knox had some well-known mentors. Who were they and how did they influence him? Knox, if I understood correctly, was concerned that there will be some challenges if you have a U.S. Air Force trying to support a naval surface force. He had some concerns about an independent air force. This was in a time when discussions of creating a U.S. Air Force sounded quite contentious. Was he concerned that air force aviators wouldn’t understand naval operations and vice versa?

The problem here centers on the question of who controls what. Knox observed post-World War I events, for example, the Washington Naval Treaty. Those events inspired Knox to write his first substantial book called “The Eclipse of American Sea Power.” He’s reeling against the fact that the average American policy maker is not educated enough to understand what they were doing when they were cutting the Fleet. After that fight in 1923, Billy Mitchell arrives and is fixated in creating an American equivalent to the British Royal Air Force, and Knox is reeling against this during his whole career because Knox is saying that the army needs airpower as much as the Navy needs airpower. But airpower for the sake of airpower is nothing. We don’t need a separate air force, he says. That’s Knox’s position for the remainder of his career.

Knox, I was interested to read, was quite the historian. In fact, one of your selections is his piece titled “Forgetting the Lessons of History.” And in my copy of your book, I underlined a section where he says he was quite frustrated with the lack of accessibility to naval archives — in particular, private collectors upset him. Why?

Knox recognized that private collectors are a major source of material that really doesn’t belong to them. They may have paid for it and they might have acquired these items for investment purposes, but from Knox’s point of view these items belonged to the nation. He became very frustrated with some of them because they liked to hang the painting on the wall or have the original commission of John Paul Jones just sitting there on the fire mantle, and Knox said that something like that does not belong on your mantle piece. It belongs to the Navy and to the nation. Through the good offices of FDR a lot of these pieces were acquired by the Navy at Navy expense for the purpose of preservation. And I must say, in the contemporary context, we have a lot of work to do in that front.

On Knox’s writings on naval leadership, he seems, at least to me, to have a reasonable position on naval ceremonies and etiquette. Why did he think that over-emphasizing naval etiquette was more dangerous than under-emphasizing it?

I think over-emphasizing on anything can be dangerous. Knox is trying to say we should be proud of our naval service and celebrate our traditions. We have to live up to the image that we want to paint for ourselves as naval professionals — that’s what he is trying to say. Etiquette for Knox does not equate to naval proficiency. For instance, you could still wear white gloves and wear a sharp naval uniform but be a terrible naval officer. That’s what he is saying. You look at some of the things we emphasize in the contemporary context: can you do enough push-ups, can you run a mile and half in the right amount of time? Knox would have said ‘that’s ridiculous – who cares?’ Knox would have said if the guy can do the job and do it well, and if they are willing to serve, and as long as they are medically fit to be under-way, I don’t care if he has a beer-belly. If he is a good sailor then he is a good sailor – and he is a shipmate. So what are we doing throwing people out that are good sailors. That’s what Knox would have said. I’m channeling his ghost as I speak. There are these superfluous bureaucratic things that Knox and his generation would be reeling against – general training, that sort of stuff. You can follow the manual all day, but you are still not going to get it, in terms of being a naval professional.

When he is talking leadership, what he is saying is ‘look, if you are getting into the weeds, the details of some poor enlisted man’s job, you are not being a leader, you are trying to be an enlisted man. Let the enlisted people do the jobs that they’ve been assigned and develop a sense of teamwork.’ He would have said you have to develop that sense of cohesion and common vision.

As a historian yourself, I want to talk a bit about your writing and research process. Where did you end up going to do most of your research on Knox?

As an analyst, I looked at his associations, and from there I looked at repositories where papers might be that make references that refer to Knox. The U.S. Naval Academy, The Nimitz Library has some great material, the Library of Congress has a gold mine of material. There’ papers in the National Archives from his official work that are hard to find, but they’re there. And of course, at the U.S. Naval War College, we have a substantial collection of interesting papers that relate to Knox and his associates. Specifically, the post-war efforts to develop professional military education standards under the Knox-King-Pye board. It was Dudley Knox and his associate Tracey Barrett Kitridge who helped Sims expand the library collection at the U.S. Naval War College from roughly 1,000 books to over 45,000 books within about a three year period – breaking all the rules and regulations required to get the job done.

The Knox-King-Pye board was another piece that I was unable to fit in this collection. I make some references to it other areas. One of the big things the board highlighted, and the reason it caused so much controversy, is that the board concluded that your average U.S. Navy flag officer was only educated to the lowest commissioned grade. If you think about that, in 1919 they are making the assertion that the average American naval professional went to the naval academy, graduated, became ensigns, and that’s the last time they had any education besides the life at sea. What Knox, King, and Pye concluded was one of the problems in the navy was the poor education of high ranking admirals. One of the people they had in mind when they wrote this was Hugh Rodman, who commanded a battleship division in the First World War. Rodman celebrated the fact that he didn’t read Clausewitz and Jomini – he thought he was just a darn good sailor. King and Knox thought he was a dullard. So in essence what Knox, King, and Pye are trying to do is say, ‘hey, flag officer, you might have the rank, but we are smarter than you.’

Also, as a writer and historian, how did you decide to organize this book? How do you organize your notes and thoughts when you are writing?

I studied with Carl Boyd and the late Craig Cameron at Old Dominion University a long time ago – and both of them had different writing methods. First and foremost as a methodological point, I was conditioned by people like Carl and Craig to study the works of great historians like Michael Howard and Peter Paret. I have been so fortunate in my past studies, as Carl personally made it possible for me to interact with Peter Paret, John Keegan, and Admiral Bobby Inman. Because of Carl, I also had the opportunity to work with and develop close friendships with historians like the late Jürgen Rohwer and Edward L. “Ned” Beach.

Since my studies at Old Dominion all those years ago, I have subsequently had the unique privilege of studying under the immediate supervision of John Hattendorf at the Naval War College and Andrew Lambert at the University of London, King’s College. Hattendorf and Lambert loom very large as inspirations for the type of historian I would like to be. Michael Howard also inspires me to focus on the human dimension, as I consider the strange phenomenon of war. If anything, my studies of past wars have convinced me that contemporary strategic thinkers ought to take the approach that, unlike armies or air forces, Knox argued that navies provided unique means, “not to make war but to preserve peace, not to be predatory, but to shield the free development of commerce, not to unsettle the world, but to stabilize it through the promotion of law and order.”

From my education as a historian, I strive to employ the method that is more closely associated with Leopold von Ranke. Through primary archival research and documentary history, I try to replicate the conditions of the time in order to understand why people acted in the way that they did at the time. I strive not to superimpose 21st century concepts upon personalities like Knox or King. I’m trying to understand why they did things in 1919 within the context of 1919. I do take sort of a broadly humanistic approach in examining historical questions.

Now, it does cause some problems for me, because I was not actually there in 1919 and I will never actually get to meet people like Knox or King. By reading their papers and by placing them into their proper historical context, however, I must say that one can get a visceral sense of what made them tick (so to speak). Since they were able to navigate the unforeseeable cybernetic challenges of technology and the collapse of empires during the unprecedented upheaval of two world wars, I must say that Knox and King would certainly have something to say about the contemporary challenges we face in the twenty-first century.

When I’m talking to contemporary strategic thinkers at the Naval War College, I also have to help them understand why the past is still important within the contemporary context. Obviously, I want people to read my writing. So, one of the challenges is to make it such that these people that are no longer with us – people like Knox and King – that they resonate with contemporary readers. I look for things that provide connections to the contemporary reader, which of course helps us discussions about the future.

I begin with that methodology. I pick people to focus on and then I look for their papers. Of course, I try to read everything I can possibly get my hands on about these people. There’s not much on Knox, unfortunately. Soon you realize that you are dealing with these complicated personalities — and you are dealing with myths in the historiography, all the while trying to figure out what made these people tick. The more you know the more complicated it gets. You have to be disciplined to focus on the themes that are the most important to understanding the person you are dealing with, but also how that person continues to be important to the contemporary reader.

Once I have all my information together I’ll rough out an outline of the themes that I want to hit on. Those then become your chapter headings, and then each chapter has its own focus. Next, you do your best to try to tie all the chapters together into a comprehensive narrative with a strong opening argument in the beginning and a strong conclusion in the end, telling the reader what it means.

My last questions have to do with Knox’s legacy. What do you think, if anything, he anticipated as future challenges for the U.S. Navy? And second, what is the single most important thing you want readers to takeaway from Knox’s work?

Knox is part of that generation of naval officers who followed the vision of the “navy second to none.” He did it through two world wars and he did it during peacetime in efforts to avoid wars in the first place. Arguably, the navy you have today is the navy that Knox and his associates built. If we don’t recognize that then we run the risk of losing what they built. I would argue that Knox is with us everyday when a U.S. Navy warship gets underway. If anything, I would hope that contemporary U.S. Naval professionals just take some time to think about the rich history and traditions of our service. In some respects I am channeling the ghosts of Knox and King in stating that I firmly believe that we must recognize our responsibility of being the curators and caretakers of our U.S. Navy for the future interests of American seapower and in framing an informed approach to the future military policy of the United States. As an aside, I was pleased the other day that they got rid of the blue navy working uniforms. It was a uniform that Knox would have taken time to write about in a negative way. It would be great to see us get back into proper naval uniforms.

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz congratulating Commodore Dudley W. Knox with a Legion of Merit in 1946. During the Second World War, Knox returned to active status with assignment to the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander in Chief, U.S. Navy (CominCh). In this capacity, Knox served at large as a strategic adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. Through their good offices, Knox established the Office of Naval History as a coequal branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence on the Operations Navy (OpNav) staff. For this service, King nominated Knox for promotion to commodore in 1945. The following year, the postwar Chief of Naval Operations, Nimitz, recognized Knox with the Legion of Merit Medal to mark his return to retired status. Nevertheless, Knox continued working within the Office of Naval History until his death in 1960.

I am chagrined that some bureaucrat, probably sitting in a cubicle in the Pentagon, decided to abandon centuries of naval tradition by abandoning our enlisted rating system in favor of the air force and army models of focusing on rank. The rating system was really emphasized by Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce who thought that military rank was ancillary to the mastery of a more focused professional trade, such as the quartermaster masters of navigation, the boatswain masters of seamanship, and the medical master corpsmen. If it is the last thing I do, our navy will someday return to its historical roots and develop a better understanding of why our U.S. Navy became what it now is within the contemporary context.

Nobody knows what the future holds, but historical understanding provides means to anticipate and adapt to the unforeseeable future. Historians frequently face challenges in dealing with people who are more interested in bureaucratic routines, or mathematically framed engineering processes, or empirically clear solutions. Historians are unable to do this, because they do not tend to offer clear answers in black and white terms. All they can really do is offer contemporary strategic decision makers an informed perspective or a recommendation for a given course of action. Historians can only stand upon the foundations provided by historical understanding, but are not very good at articulating their ideas within the contemporary context as the engineers, lawyers, politicians, and policy-types tend to dominate the contemporary discussions of future strategy.

Basically, I think it is important for us as naval professionals to consistently seek an informed understanding of the past in order to know in clear terms the influence of history upon seapower and in shaping the future military policy of the United States.

Dr. Kohnen, thanks so much for taking the time to chat. All the best to you.

Thank You, Chris. I enjoyed it.

David Kohnen earned a PhD with the Laughton Professor of Naval History at the University of London (Kings College London). As a maritime historian, he concentrates on naval strategy, organizations, and organizational group dynamics. Focusing on these general themes, he edited the works of Commodore Dudley W. Knox to examine historical foundations in contemporary maritime affairs in, 21st Century Knox: Influence, Sea Power, and History for the Modern Era (Naval Institute Press, 2016). In his previous book, Kohnen focused on the transatlantic alliance between the British Empire and United States in, Commanders Winn and Knowles: Winning the U-Boat War with Intelligence (Enigma Press, 1999).

Outside of his scholarly work, Kohnen’s naval service in the active and reserve ranks include two deployments afloat in Middle Eastern waters, two ashore in Iraq, and one supporting landlocked operations in Afghanistan. Balancing work as a Naval War College civil service instructor, Kohnen also serves in the U.S. Naval Reserve with the Executive Programs faculty at the National Intelligence University in Washington, D.C. The comments and opinions in this interview are his own and do not represent the opinions of the U.S Navy or the U.S. Department of Defense.

Christopher Nelson is a U.S. Naval Intelligence Officer currently stationed in the Pacific. The questions and comments above are his personal opinions and do not reflect the opinions of the U.S. Navy or the U.S. Department of Defense.