By Dmitry Filipoff

Last week CIMSEC featured short stories submitted in response to our Call for Fiction.

Authors explored a wide variety of futures and scenarios. From unique naval capabilities and platforms, to devious tactics and undersea warfare on foreign worlds, authors imagined an array of thought-provoking scenarios.

Below are the stories and authors that featured during CIMSEC’s 2024 Fiction Week. We thank them for their excellent contributions.

“False Flag,” by Tyler Totten

“Herera looked up from his command display to see empty containerized missile launchers being hauled over the side linked by heavy wire rope. He wasn’t sure why until he saw the next layer of containers opening in turn and starting their launch sequence. Herera realized with horror that the ship could still contain dozens of additional missiles.”

“Aleutian Ambush,” by Addison Pellerano

“Heart racing, Andrew stumbled his way into the team’s modified operation center, several monitors hooked up to a couple different computers and a Starlink terminal. RW1 Ruiz Castro sat in front of the monitors, receiving the data feeds from multiple of their USVs. RW1 looked up as LTJG Lee entered through the door frame, the blue light of the ops center casting a glow across the space. ‘That was something else, Sir. I am glad no leakers got through,’ he said softly.”

“Rendezvous,” by David Strachan

“Shilpa shook her head. How did we get here? It was inevitable that astrobiology, much like all of science itself, would be slowly subsumed by the machinations of geostrategy and power politics, but for the scientist in her, it was as absurd as it was immoral. She bristled at the notion of exporting human conflict to another world, and in the name of scientific exploration no less. If we cannot explore in peace, should we even explore at all?”

“Veins of Valour,” by Robert Burton

“For what seemed an eternity, they remained hidden beneath the canopy, their breaths held in anticipation. Finally, the distant hum of the drones faded into the distance, leaving behind an eerie silence. Before they shed their camouflage, Lieutenant Reynolds took advantage of the tarp’s electromagnetic shielding properties to quickly assess her patient’s vitals.”

“The Impending Tide,” by Mike Hanson

“As it came closer he noticed its markings were different than he remembered. Troops immediately debarked the helicopter and began unloading supplies. As he came closer he could see their blue uniforms. In large letters on the side of the helicopter were the letters ‘PLANMC.’ These were not Americans. The Chinese had landed.”

“Lessons Learned,” by Paul Viscovich

“For their part, the drones in the swarm had no active sensors and were dependent on the accuracy of their pre-programmed flight path until getting close enough for units of the scouting pods to detect the infrared signature of exhaust gases from the enemy’s stacks. The usual noise level in CIC ticked down a few decibels as decision-makers and watchstanders alike strained to follow reports of the unfolding attack. Petty Officer Gary Woytowych, seated at his NTDS console, reported events as they happened.”

“Visual on the Marlin,” by Karl Flynn

“Pahlavi commanded the ROV to slowly move toward the open torpedo tube using the station-keeping mode. He was intently focusing on lining up the resupply capsule with the open tube. At this point, the ROV’s control software was doing most of the work, but Pahlavi could still feel himself sweating. After what seemed like an agonizingly long approach, the finned end of the capsule disappeared into the open torpedo tube.”

“Dark Ocean,” by Vince Vanterpool

“This area was a bald patch on his displays, completely devoid of visually stimulating information, much like the dark ocean Corbin witnessed just before taking the watch, and like it had been for the last two days. Despite the uniformly blank patch of pixels on the screen, Corbin knew that the area was under heavy scrutiny from both above and within the area; dozens of eyes and ears straining in the void to catch a single glimpse or inadvertent squeak of a possible target.”

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at [email protected].

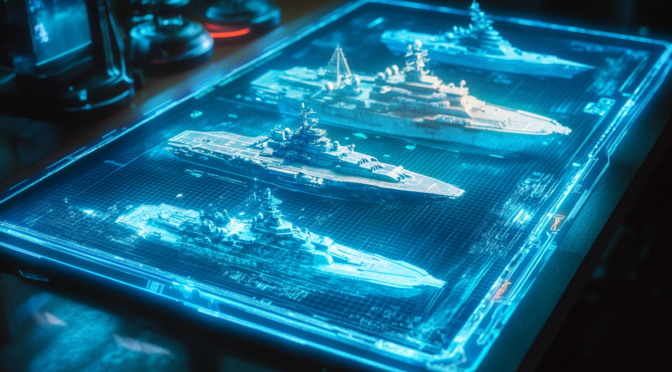

Featured Image: Art created with Midjourney AI.