Weber, David. Uncompromising Honor. Baen, 2018. 784 pp. $28.00/hardcover.

By Mark Vandroff

There is a special challenge in reviewing the fourteenth book in an iconic, best-selling series. The point of a book review is to advise potential readers if they should invest their time and money toward reading the work in question. For true fans of author David Weber, who have thirstily imbibed the first thirteen installments of the Honor Harrington saga, nothing offered in this essay could possibly deter them from immediately engaging with this long-awaited tome.

For those who are not yet smitten by the charms of the science fiction milieu known as the Honorverse, book fourteen, while highly entertaining in its own right, is best experienced as a follow-on to the earlier books in the story. The task of this review is then two-fold; to entice those who have yet to experience David Weber’s art to begin a literary journey that will eventually culminate in the reading of this outstanding book, while at the same time whetting the appetite of the experienced Honorphile before he or she feasts upon Uncompromising Honor.

A Classic and Engrossing Universe

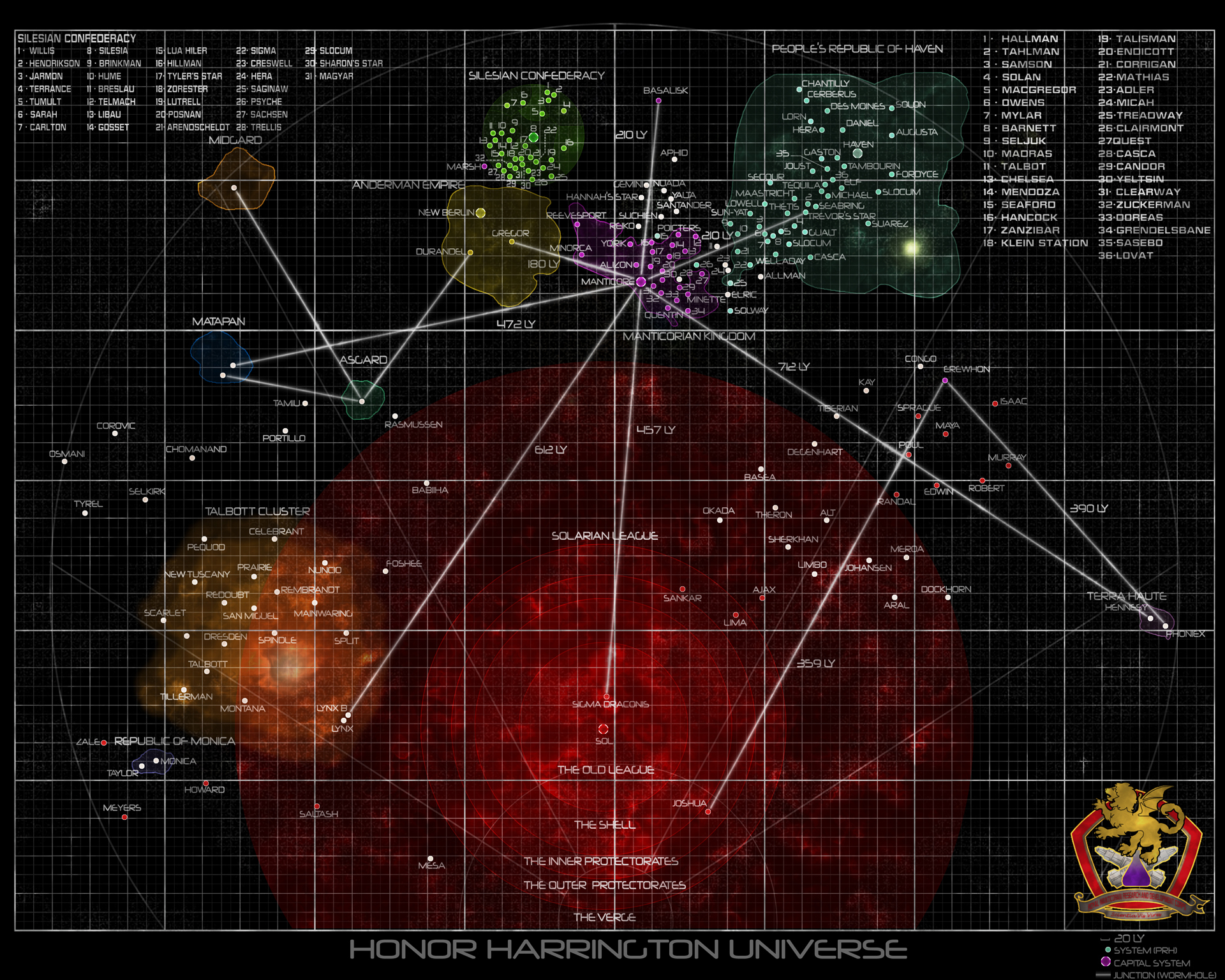

David Weber’s Honorverse consists of fourteen books in the main Honor Harrington series, the four books of the Saganami Island series, the three books of the Crown of Slaves series, and various other short story anthologies, prequels, and novellas. The first book of the Honor Harrington series, On Basilisk Station, introduces the reader to Commander Honor Harrington who serves in the Royal Manticoran Navy during tumultuous times.

The books of the Honor Harrington series explore roughly 22 years of the military, political, and social history of Manticore, its allies, and its adversaries, while following the career of a remarkable woman as she rises through the ranks from command of a light cruiser to service at the highest levels of military and political leadership. The two main companion series explore concurrent events in other parts of the galaxy and provide context and backstory for characters that will eventually impact the main series. While the side series are worthy reading in their own right, they are best experienced as background material to the main storyline.

Several factors combine to make Weber’s books both enjoyable as fiction and profound as works of art. Weber works hard to provide a self-sustaining and consistent universe. As an example, any science fiction has to overcome the problem of the impossibility, as our current understanding of physics dictates, of travelling in excess of the speed of light. David Weber handles this in a well thought-out explanation of “new science” that imposes both capabilities and important limitations on the occupants of his universe. All the fictional technology in the Honorverse is self-consistent and does not allow for easy fixes to wish away problems for either the protagonist or antagonist. Manticore’s technology is superior but not magical, and inventive opponents often craft effective counters.

The wide range of political and social systems extant on the worlds with which Manticore must interact allows Weber to explore many different facets of the human condition. 1900 years after human beings first left Earth in an attempt to colonize habitable planets around the galaxy, a wide variety of social and political structures have arisen on the worlds that humanity now occupies. The Star Kingdom of Manticore is a constitutional monarchy that calls three habitable planets in a binary star system home and maintains a range of alliances with foreign star systems. We discover a planet where the Christian religion ennobles and sustains its population, and another where religious fanaticism has created a planet-wide, Christian version of ISIS. Some democracies produce wise government, responsive to the needs of its citizens and others produce entrenched bureaucracies which exploit their people. Others take the form of imperialist welfare states, forced to conquer for the sake of propping up a broken system while using authoritarian means to stifle dissent. These political entities find themselves entangled in vicious wars and subversion as great power competition makes its way into the space age on a galactic scale.

Battles are described in vivid, suspenseful detail. Usually portrayed through the eyes of multiple participants, Weber’s strong writing places the reader on the bridge and in the reactor plant of powerful warships as the crews fight to accomplish their missions and fulfill their duty. A well-crafted formula of naval capability and tactics elegantly combines the sudden destruction of missile warfare with close-range fires reminiscent of the age of sail. Ships often employ signature control, electronic warfare, and drones to gain the upper hand through crafty means. Through this well-formulated vision of space combat Weber thrusts his characters into a wide range of operational encounters and tactical dilemmas that test their ability to command and adapt.

Weber takes the time to create rich backgrounds for multiple characters. The good guys are never entirely perfect and the bad guys are rarely all bad. Weber is also willing to have key characters die along the way and when an important battle is done, readers often feel as if they have lost friends in action. Weber’s characters often have to remain resilient in the face of tremendous loss, lead battered and demoralized crews, and cope with the unsatisfactory taste of bittersweet victory.

War, Deceit, and Honor

Uncompromising Honor picks up at the end of the Second Battle of Manticore and tells the story of what Honorverse fans will likely come to refer to as the Solarian War. The book covers the nine months between July and March in the 1922nd and 1923rd year after humanity began stellar colonization. The Solarian League Navy, unable to defeat Manticore and the rest of its alliance in a battle between the heaviest ships of the wall, embarks upon a campaign of economic warfare against Marticore’s trading partners. Manticore’s response is to cripple the Solarian economy by taking possession of all known galactic wormhole junctions used by merchant ships to reduce their transit times. By seizing control of the geographic chokepoints of galactic commerce Manticore aims to starve the Solarian League of its ability to maintain the industrial production that supports it economy.

These opposing strategies set up the first great battle of Uncompromising Honor, the Battle of Ajay Hyper Bridge. The Solarians, armed with a large fleet of 50 battlecruisers and additional lighter units, need to pass their task force through the Ajay wormhole in order to conduct their assigned system raids. Manticore must hold the wormhole so its supply ships can sustain their deployed forces. The Solarians have numbers on their side and Manticore has superior technology. 78 pages of white-knuckled suspense tell the tale of this key battle in the Solarian War.

The second major battle scene in Uncompromising Honor is the Battle of Hypatia. Hypatia is a star nation that is in the midst of voting to leave the Solarian League. A small task group of Manticoran cruisers and destroyers is in Hypatian space awaiting the results of the plebiscite. Should Hypatia vote to become independent of the Solarian League, the Manticoran ships are ready to deliver the Star Kingdom’s new ambassador to this potential key ally. However, the Solarian League Navy shows up with several dozen battlecruisers with orders to prevent Hypatian secession, even to the point of committing war crimes to achieve their mission.

The choices presented to the Manticoran commander harken back to the solemn “Last View” ceremony at Manticore’s naval academy. Graduating midshipmen are presented with the history of the academy’s namesake, Commodore Edward Saganami, and his final battle against Silesian pirates. In both the Last View and the Battle of Hypatia, Weber masterfully explores the difficult moral obligations of a commander to both his mission and his people. The question of when should a commander risk devastating losses to the forces under his command in order to accomplish a critical mission is on display as both sides grapple to do their duty as they understand it.

Between and after the battles, Weber continues to develop the political and economic storyline of the galaxy. The shadowy Mesan Alignment continues to execute its plan and influence star nations in ways seen and unseen. Characters on Earth, Manticore, Haven, and in the Talbott and Maya Sectors all struggle. Some struggle for power and wealth, some struggle for understanding, and a few noble souls struggle to do the right thing. There are triumphs and tragedies along the way spread out over much of the inhabited galaxy. In the end these struggles and machinations lead to climatic conflicts in the Beowulf system, and finally in the home system of Earth itself.

Despite, or perhaps because of all the military and political action in Uncompromising Honor, it is the human touches that make this book so gripping. We are treated to the planet Grayson’s favorite girl next door (assuming you live next door to a Steadholder’s palace), Lieutenant Abigail Hearns of the Grayson Space Navy, as she goes on her first date with a handsome young man with a questionable background from the Seraphim system in one of Manticore’s more upscale dining establishments. This is also the first of the mainline Honor Harrington books where multiple treecats play important roles and the reader is treated with extensive treecat dialog and monologue. Treecats are the native sentient species of one of the Manticore system’s habitable planets. The close relationship of Honor to her small, furry, cute, and at times lethal, treecat friend Nimitz plays an important role in the plotline of the series. In this book, multiple human characters have important treecat relationships. By the end of Uncompromising Honor, we understand that treecats are not only sentient, but that they bring a unique perspective on understanding humanity in a way that only a non-human species that can experience human feeling could provide.

A Tale Continues…

While Uncompromising Honor does allow for a satisfying conclusion, there is clearly more left to tell and many questions remain tantalizingly unanswered. While David Weber’s fans will greatly enjoy Uncompromising Honor they will be left with the same gripping emotional state at the end of this book as with the others, eagerly awaiting the next installment of this magnificent series.

Captain Mark Vandroff is a 1989 graduate of the United States Naval Academy. His 28 years of commissioned service include duty as both a Surface Warfare and Engineering Duty Officer. He was formerly the Major Program Manager for the DDG 51 program and is currently the Commanding Officer of Naval Surface Warfare Center, Carderock. The views expressed in this article are the author’s personal views and do not reflect the official position of the Department of Defense or Department of the Navy.

Featured Image: Adaptation of the cover of the Honor Harrington’s novel Honor Among Enemies by Genkkis via DeviantArt