By Andrea Daolio

The Persian Gulf recently made headlines across the world due to clashes between Iran, the U.S., the U.K., and regional Arab states. Of grave concern, the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf is a chokepoint for global shipping routes where much of the world’s energy supply passes. While tensions have remained high in the region for quite some time, every incident bears some consequence for global stability.

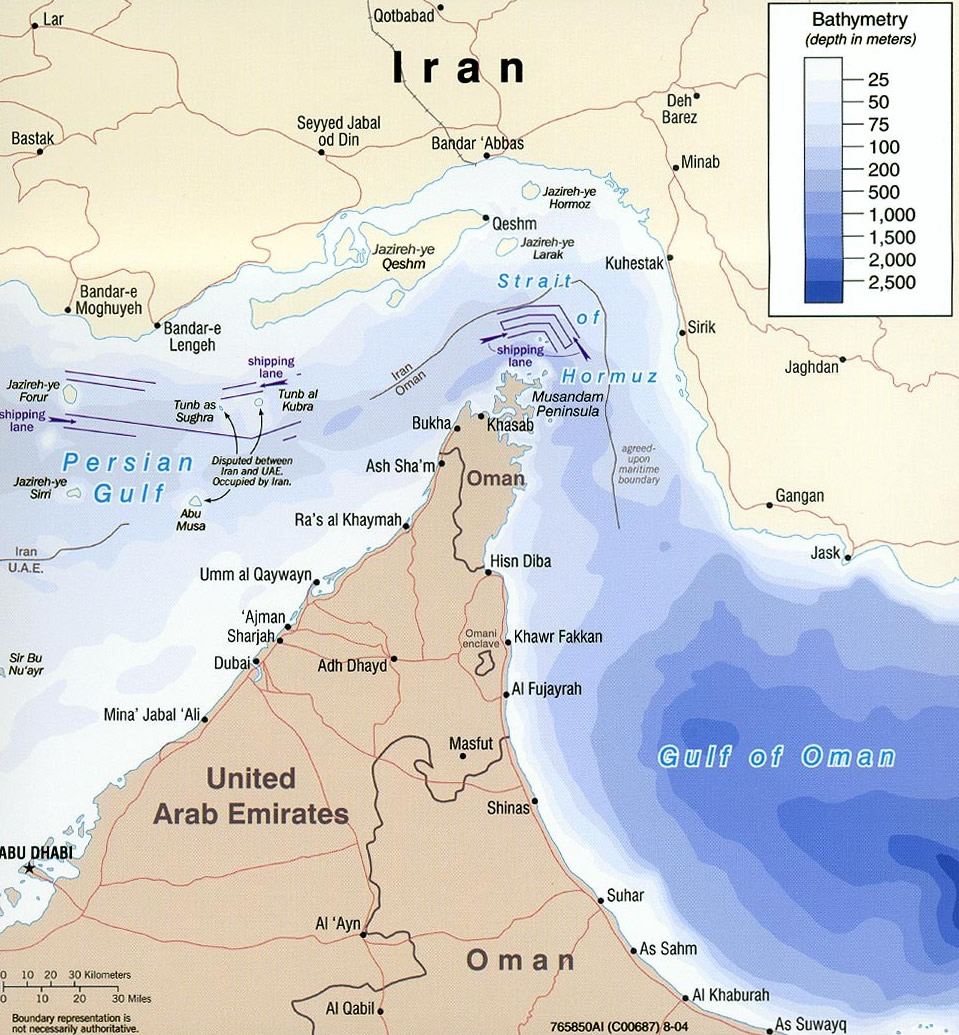

The Persian Gulf (or Arabian Gulf according to some Arab countries, showing how the rivalry also extends to the very name of the sea) is an inland sea that is connected to the Gulf of Oman and the Indian Ocean through the Strait of Hormuz, a feature that is only 21 miles wide at its narrowest point. With its powerful littoral navy homeported in bases all around the Strait, from the main base at Bandar Abbas to smaller ports at Jask, Qeshm and Abu Musa, Iran is clearly very well-positioned to attempt a closure of the Strait.

Freedom of navigation has been long guaranteed by the United States Navy and its allies, but today this is increasingly challenged, from China in the South China Sea to Iran in the Persian Gulf. With respect to Iran the U.S. Navy already dealt a strong blow to the Iranian fleet in 1988 with Operation Praying Mantis, but the situation has radically changed since.1 In 1988 Iran was locked in a protracted bloody war with Iraq, and its forces were still trying to recover from the purges of the Islamic Revolution. Iran was also faced with a lack of supplies and spare parts for its largely American or European-built arsenal. It is no surprise then that American naval forces were able to sink or severely damage half of Iran’s operational fleet in a single day.

The Iranian Navy has changed plenty in the past three decades. Now the IRIN (Islamic Republic of Iran Navy) can field three Russian-built Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines and a vast array of small but deadly midget submarines that could prove extremely dangerous in the shallow waters of the Persian Gulf (that has an average depth of only 160 ft and a maximum depth of 300 ft). The Iranian surface fleet is still greatly inferior to the U.S. Navy and can only rely on a few small frigates. But it also includes a great number of small combatants, often of no more than 200 tons but armed with 2-4 modern anti-ship missiles with a range sufficient enough to hit almost any area on the opposite side of the Gulf from their home bases. But even the boats without ASMs can be a great threat in the confined waters of the Persian Gulf and attack enemy ships with surprise attacks and swarm tactics that could overwhelm even better armed American ships.2 To add to the threat, a large number of land-based anti-ship missiles and ballistic missiles are now in the inventory of the Iranian Armed Forces. These not only endanger ships in the Persian Gulf, but bases and infrastructure across the Arabian Peninsula are under threat.3

Moreover, Iran has maintained a mining capability that has already proven deadly for commercial ships and for the U.S. Navy back in the ‘80s. Since World War II, of the 19 U.S. ships sunk or seriously damaged by attack, mines were responsible for 15. Even old mines can pose a great threat to ships and will require extensive operations to clear them. Mines dropped from innocent-looking fishing boats can block shipping lanes, deter transits, all while giving the aggressor some cloak of deniability.

While these weapons are extremely dangerous for American forces in the area and Iran could carry out a deadly first strike against the U.S. and its allies, the Iranian regime is well aware that an American counter-attack could destroy their military. But if Iranian forces limit themselves to small-scale attacks that help maintain a semblance of deniability, then Iran can still cause havoc to shipping4 and destabilize the global economy as even small incidents can make oil prices and shipping insurance increase considerably.5

Expanding the Roles of Arab Allies

In order to reduce their dependence on the United States Navy, which is no longer looking to maintain a carrier strike group in the Gulf on a full-time basis, Arab Allies should concentrate more on fielding small and agile ships armed with ASMs missiles on the model of the Iranian Navy. But the trend for Gulf States in recent years has been to upgrade their navies with larger and more capable surface combatants,6 but while Saudi Arabia can base its more powerful ships in the Red Sea, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates can only place their ships a few miles from numerous Iranian missiles ready to strike them. If Arab states instead build a fleet of more numerous small and fast surface combatants they can hope to escape any first strike by Iran by distributing their forces and then countering Iran with reciprocal small-boat missile attacks. They must also look to expand their mine countermeasure forces to keep up with the platform-intensive activity of minesweeping.

While America and its Arab Allies can greatly contribute (and already are greatly contributing) to maintaining security in the Strait of Hormuz, Asian countries that are the main importers of Gulf oil should do their part. More than 75 percent of these crude oil exports are destined for Asian markets, with Japan, India, South Korea and China the largest importers. Moreover, Iranian actions are angering even those countries that showed support in the past to Iran or that refused to follow the American “maximum pressure” campaign of Sanctions. European countries that tried to save the Iran deal are now reconsidering their stance as Iran looks to continue enriching uranium and attack civilian shipping.7

Iranian threats can be mitigated through innovating in energy infrastructure. Saudi Arabia already has a long East-West pipeline, connecting the oil fields near the Persian Gulf to the port of Yanbu on the Red Sea opposite Egypt. If more pipelines are built toward the port of Yanbu, and other ports on the Red Sea are adapted to service tankers, a large portion of Saudi Arabia’s oil and gas can be exported from this area, safe from Iranian naval threats. As the Saudi monarchy has close ties with many neighboring Arab countries, regional states could develop a joint plan to export their oil and gas from the Red Sea, in this way reducing their dependence on the Strait of Hormuz. Moreover, if Arab States export more oil and gas from the Red Sea, then Iran will increasingly become the only state that is truly dependent on the Strait of Hormuz.

Conclusion

While the Iranian Armed Forces have greatly improved in recent decades and can be a serious threat to commercial and military assets transiting the Strait of Hormuz, there are many ways to counter these forces and maintain freedom of navigation. Since Iran has developed many asymmetric tactics to counter the U.S. and its allies, the best way to respond is to develop opposing asymmetric tactics and unconventional means, both military and political, to throw Iran off balance.

Andrea Daolio, from Italy, has an engineering background and a long-standing passion for wargaming and for geopolitical, historical and military topics. He has been a finalist in New York’s MTA Genius Transit Challenge. He is currently collaborating with video game developer Slitherine on the popular wargame Command: Modern Air/Naval Operations. His views are his own.

References

1. David B. Crist, “Gulf of Conflict: A History of U.S.-Iranian Confrontation at Sea,” June 2009, The Washington Institute. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus95.pdf.

2. Sune Engel Rsmussen, “Iran’s Fast Boats and Mines Bring Guerilla Tactics to Persian Gulf,” The Wall Street Journal, May 30, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/irans-fast-boats-and-mines-bring-guerrilla-tactics-to-persian-gulf-11559208602

3. Anthony H. Cordesman and Abdullah Toukan, Iran and the Gulf Military Balance, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 3, 2016. https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/161004_Iran_Gulf_Military_Balance.pdf

4. Vivian Yee, “Claim of Attacks on 4 Oil Vessels Raises Tensions in Middle East, The New York Times, May 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-oil-tanker-sabotage.html

5. Jonathan Saul, “Ship Insurance Costs Soar After Middle East Tanker Attacks,” Reuters, June 14, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/mideast-attacks-insurance/ship-insurance-costs-soar-after-middle-east-tanker-attacks-idUSL8N23L2ND

6. Chuck Hill, “Saudi Navy Expansion Program,” Center for International Maritime Security, December 9, 2015. https://cimsec.org/saudi-navy-expansion-program/18474

7. Alexandra Ma, “Europe Reportedly Threatens to Activate Nuclear-Deal Clause that COULD Reimpose Sanctions and push Iran into China and Russia’s Arms,” Business Insider, July 5, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/iran-nuclear-deal-europe-could-activate-dispute-resolution-sanctions-report-2019-7?IR=T

Featured Image: RIYADH, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Feb. 10, 2013) Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Adm. Jonathan Greenert meets with heads of the Royal Saudi Naval Forces (RSNF) program at the RSNF head quarters building. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Peter D. Lawlor/Released)