By J. Overton

As of mid-March 2022, the nation of Ukraine, invaded and partially occupied by Russia, effectively has no Navy. On March 3, 2022, Ukraine scuttled its Navy’s flagship to prevent the vessel’s capture by invading Russian forces, and some of its remaining ships – in this case transferred ex-U.S. Coast Guard cutters three to four decades old – have been destroyed. Recent losses aside, the two nations’ naval forces were unevenly matched before the current war began. According to retired U.S. Navy Admiral and former Naval Forces Europe commander James Foggo, “If you go back to 2014, when the Russians essentially blockaded the Ukrainian fleet, they were both at the time in [the Crimean port of] Sevastopol and they had upwards of 80 ships. When [Russia] sank all these old relics in the harbor and the Ukrainians couldn’t get out, they lost their navy. They lost their naval headquarters. They lost their naval academy. And they lost some of their officers that were sympathetic to the Russian side…The balance is tipped grossly in favor of the Russians.”

Being without a Navy, fortunately, does not mean that there is no seapower acting in Ukraine’s interest, or that there are no naval lessons or innovations coming from this terrible and hopefully short conflict. From Maine to Majorca, Turkey to Panama, a distributed network of international maritime actors has emerged in response to Russian aggression. It manifests a theory that was developed 17 years ago — the “1,000 Ship Navy” (TSN).

The TSN concept was publicized in remarks that then-Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael Mullen made at the Naval War College’s 2005 Current Strategy Forum. In those and following remarks and articles, he explained the idea: “…we could broaden our definition of what constitutes the fleet. The United States Navy cannot, by itself, preserve the freedom and security of the entire maritime domain…It must count on assistance from like-minded nations interested in using the sea for lawful purposes … I envision a ‘1,000-ship navy’ – a fleet-in-being, if you will, made up of the best capabilities of all freedom-loving navies of the world.”

Saying that the U.S. Navy needed “assistance” was not always well-received within the U.S. or by those hoped-for global partners. The name was an attempt to more clearly define a nebulous desire for broader global maritime partnerships. It did not literally mean 1,000 ships, or necessarily any ships, since Mullen described the TSN of being composed of “capabilities,” not only ships. Attempts were made to give concrete examples of how a TSN would look and function, to name it something more palatable (like “Global Maritime Partnership”), and in a Naval War College Review article from 2007, to define steps to “revive enthusiasm” for it only two years after it was first publicized.

In the first few months of 2022, however, a TSN is finally forming. Its nature as a cooperative effort of international maritime capabilities, biased toward action rather than regulation, pursuing a common objective below the threshold of war – makes it recognizable as such. But now realized and observable, in its very early stages, the character of the TSN emerging in reaction to the Russia-Ukraine war is different in three significant ways from what was originally theorized.

The theoretical TSN was a collection of primarily nation-state naval capabilities used against non-state actors and natural disasters. But this new TSN is a collection of mostly interagency, non-naval, and sometimes non-state capabilities, using diplomatic and economic power, and even guerrilla tactics, against a nation state’s (Russia’s) elements of maritime and national power.

This new TSN’s first action was arguably when, after the Irish government was unable to stop a pending Russian naval exercise in its fishing grounds, Irish fisherman took to seas by the hundreds to legally, peacefully obstruct the exercise (notably different from State-directed Chinese fishing fleets also used to impact naval exercises). Their efforts were successful and prompted Russia’s defense minister to relocate the exercise in late January 2022.

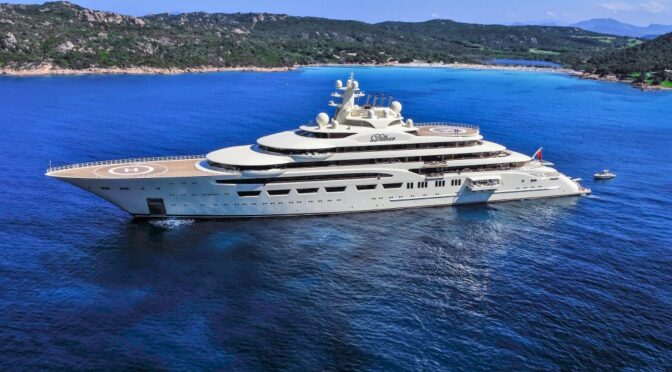

Ongoing operations from local jurisdictions and individual actors include striking targets of opportunity with the general objective of depleting or hindering Russia’s maritime power and interests, such as turning Russian vessels away from ports and sabotaging or impounding yachts owned by Russian oligarchs.

The theoretical TSN was envisioned as an adjunct to the world’s most powerful Navy. The new TSN formed organically and disparately. The world’s three biggest shipping lines suspended non-essential deliveries to Russia, joining a growing list of companies shunning Moscow amid Western sanctions over its invasion of Ukraine. Turkey, not considered a belligerent in this conflict, has restricted the passage of warships from warring states – notably, Russia – through the Bosphorous. The Russian Navy’s attacks – deliberate or not – on third-country merchant shipping are also helping unite maritime powers, who otherwise would have minimal interests in the war, in opposition to Russia.

The theoretical TSN envisioned the U.S. providing communications and intelligence networks for a “common operating picture” among partners in the TSN. The new TSN relies on open source communications and intelligence, available to mostly everyone with an internet or cell phone connection.

Black Sea shipping traffic can be monitored in real-time online, without particular equipment training, and the location of Russian ships, or Russian-crewed ships, in other parts of the world is being shared via traditional and social media. TSN actors – independent actors, nation states, and international agencies and corporations – guided by a common goal, will act on this information as they see fit.

Conclusion

Attention related to the international community’s direct involvement in the war remains mostly focused on landpower. The maritime component of this war – which, with a few exceptions, bears little resemblance to common perceptions of naval warfare – is covered mostly anecdotally. This horrible conflict has however been the catalyst that set in motion a concept which a decade-and-a-half ago was considered too idealistic. The emerging TSN may be an example of the limits, or decline, of U.S. naval power. It may turn out to be too uncoordinated and tactically sporadic to provide any strategic benefits to Ukraine or damage to Russia. Its Nelsonian standing order may remain nothing more substantive than the profane, defiant “last words” of a Ukrainian soldier.

But this TSN is an undeniable “global force for good,” in an early and disparate iteration, quickly spreading across the maritime domain with more potential reach than any single nation’s Navy. It just took Russian aggression – not American encouragement – to put it to sea.

J. Overton is Non-Resident Fellow at the Modern Institute at West Point. He was previously an adjunct professor for the Naval War College and Marine Corps Command and Staff College, and served in the U.S. Coast Guard. He is a graduate of the Naval War College, the Joint Forces Staff College, and Northern Arizona University. He lives in the Pacific Northwest. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Navy, or Department of Defense.

Featured Image: The superyacht Dilbar owned by Russian oligarch Alisher Usmanov. (Photo via Yachtandboatguide.com)