By Dmitry Filipoff

CIMSEC had the opportunity to discuss with Phillips Payson O’Brien his latest book, The Second Most Powerful Man in the World: The Life of Admiral William D. Leahy, Roosevelt’s Chief of Staff. In this conversation O’Brien sheds light on Admiral Bill Leahy’s momentous contributions to U.S. strategy and foreign policy in the critical years during and following World War II, as well as his personal style of discreetly exercising influence as “the second most powerful man in the world.”

As the title clearly suggests, Admiral Leahy wielded tremendous power and influence, especially during the interwar period, WWII, and in the immediate aftermath of the war. What were the sources of his power and influence that led you to describe him as “the second most powerful man in the world”?

The single most important element in Leahy’s rise to the top of the U.S. government in World War II was his longstanding friendship with Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The two men first met in the Navy Department in 1913 and grew to not only enjoy each other’s company, but to trust each other’s instincts. In the case of Roosevelt, this was special. Roosevelt, though outwardly charming, was not a naturally trusting individual. As he rose up politically, he was surrounded by ambitious people trying to take advantage of his power to further their own careers—and he often held them at arm’s length because of this. In the case of Leahy, he came across someone who was happy not to be in the limelight, but motivated to serve his interests first and foremost. It was why, as soon as Roosevelt became president, he started promoting Leahy up the naval chain of command, making sure that the admiral received every major position he could—chief of the Bureau of Navigation, commander of the Battle Force, and culminating in Leahy’s appointment as Chief of Naval Operations (1937-1939).

The two men also shared a similar strategic outlook. They were committed believers in the importance of a strong American navy and both had been strongly influenced by the ideas of Alfred Thayer Mahan. It meant that when they did work together running the American Navy in the 1930s, they instinctively reinforced each other’s perceptions and made a very strong team. By the time World War II started for the U.S., the American Navy was more the creation of these two men than any others.

Leahy actually retired formally in 1939, having reached mandatory retirement age. However by this time Roosevelt had made the decision that if a war did break out in the near future he would want to bring Leahy back to help him run it. He started discussing such a role with Leahy in the spring of 1939, and the two men honed the specifics of the role during the coming years. To allow this to happen, Roosevelt kept Leahy employed. He first made him governor of Puerto Rico, so that Leahy could help build up naval bases in the Caribbean. He then made Leahy ambassador to Vichy France. Both of these positions were a sign of the special trust the president had in the admiral.

Beyond the close personal relationship between Leahy and Roosevelt, the admiral had a number of key skills. He was instinctively political (this is discussed in more detail later) and he was undoubtedly competent and thorough. Though not the most deeply intellectual, Leahy had a way of getting a job done that was invaluable. When you combine this with his lack of interest in personal publicity, it was a powerful cocktail and made him stand out in a Washington DC populated by people who were always on the lookout for personal glory.

Soon after the U.S. entered WWII, it was confronted with a major strategic decision on how it should define specific war production priorities for its tremendous industrial might, a decision you described in the book as perhaps one of the most strategic decisions of the war for the U.S. What was Admiral Leahy’s role in these deliberations?

Usually strategy in WWII is seen as some great debate over where and when military force should be used. Discussions over whether the U.S. should have invaded France in 1943 or 1944, or whether it should fight a Germany-First war are perhaps the most famous examples of this. In our focus on the where and when, however, what is almost always overlooked is the what. All the great powers in World War II had to decide what to build in terms of equipment, force structure, how to balance needs between armies, navies, and air forces, as well as within the services such as balancing needs between, for example, fighters and bombers or tanks and trucks.

This was a far more involved process for the U.S. than many realize and William Leahy was at the heart of this debate. Not long after Pearl Harbor was attacked, President Roosevelt approved an arms construction plan of enormous depth and breadth which was nicknamed the Victory Program. However, by the summer of 1942, it was clear that even with the largest and most powerful economy in the world the U.S. could not build nearly as much equipment as was called for by the Victory Plan. A crisis ensued and hard choices needed to be made in the second half of 1942 about what would be built, and even more controversially, what would have to be cut.

Leahy was the most important person in the government, except for Roosevelt, in determining these priorities. By this point he was both the president’s chief of staff (the closest modern equivalent would be the National Security Adviser) and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Wearing his two hats he fought to cut army construction and focus on aircraft and aircraft carrier construction. By December 1942 he had emerged triumphant, and both his targets received the highest priority for the U.S. in 1943 and 1944. On the other hand, production for the army, particularly tank construction, was slashed. This decision, which has received little historical discussion, determined what the U.S. could and could not do during the war.

Another strategic choice that Leahy was instrumental in making at this time was about the size of U.S. armed forces. The other joint chiefs favored inducting huge numbers of men and women into the forces, at one point devising a plan for more than ten million U.S. military personnel. That plan, however, soon clashed headlong with the need to keep skilled personnel working in the economy to produce war material. Leahy was the only military officer to serve on a small committee chosen by Roosevelt to examine the question of military and civilian employment, and he came down strongly in favor of more equipment production and a small army. His preference was one of the reasons that the U.S. fought the war that it did. The United States opted for an equipment heavy, personnel-light military force structure that kept casualties down.

Admiral Leahy chaired the Joint Chiefs of Staff during World War II (and afterward) and also participated in major strategic conferences of the war, such as at Yalta and Potsdam. What was his influence on wartime grand strategy and the conduct of WWII?

Leahy took over as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs holding very different strategic priorities from the Chief of Staff of the Army, George Marshall. Looking at the war from an overall perspective, Leahy did not want the United States to fight a Germany-First war, which Marshall and many others, including Winston Churchill, strongly supported. Leahy was worried that if the Japanese were allowed to entrench themselves in their Pacific empire while the U.S. threw everything into the war against Germany, that it would have devastating consequences. It would, he feared, take many extra years and a great deal of American blood to take the fight to Tokyo.

In this, Leahy walked arm-in-arm with Chief of Naval Operations Ernest King. The Leahy-King alliance ended up triumphing in this fight, and contrary to what is widely believed, at no time in the war did the United States fight a Germany-First strategy. In 1942 the U.S. fought, if anything, a Japan-First war. The United States sent more overall equipment to the Pacific over Europe or North Africa. In 1943 and 1944 the U.S. fought two different wars. The Army and Army Air Force did prioritize the war against Germany—sending approximately two-thirds of their equipment to Europe. The Navy, on the other hand, sent at least 90 percent of its strength (including one of the largest air forces in the world) to fight Japan. This meant that in overall terms the United States, under Leahy’s watchful eye, fought a war almost evenly balanced between Europe and the Pacific but weighed slightly more toward the latter.

When it came to the war against Germany, Leahy’s vision was the one the United States followed more than any other chief’s. Leahy was the only chief who supported the invasion of North Africa in 1942, better known as the Torch Landings. Indeed, Leahy had been the first major policymaker who proposed a North African invasion to Roosevelt, suggesting such an operation in the summer of 1941 (when Leahy was ambassador to Vichy France). Leahy believed such an operation would confine Germany to the European continent, and allow for Allied domination of the Atlantic. Understanding Leahy’s strong support for Torch helps explain why Roosevelt backed the operation over the strong opposition of Marshall and King almost immediately after Leahy became Chief of Staff.

After Torch, Leahy’s number one goal for the war in Europe was to delay the invasion of France until 1944. He did not want to try an invasion in 1943, which Marshall supported, because Leahy believed it was an unnecessary risk which could result in high U.S. casualties (and he also believed it would deprive the war against Japan of needed equipment). He thus helped undermine the U.S. army’s attempt to get British approval for any 1943 invasion. However, once this was ruled out, Leahy enthusiastically supported D-Day in 1944, and helped force the British to accept this position at the grand strategic conferences in Washington, Quebec, Cairo, and Tehran which were held in 1943.

Following the death of his close friend President Roosevelt and the end of WWII, Admiral Leahy continued to be highly influential in the Truman administration and played a major role in many critical postwar questions. How did Admiral Leahy shape postwar formulations of the U.S. defense establishment and international order?

Franklin Roosevelt’s death led to a significant change in Leahy’s influence. For the two years before FDR died, Leahy was the most influential policymaker in the White House, as Harry Hopkins (who was more influential in 1942 when Leahy became chief of staff) saw his influence decline. However, Leahy had no pre-existing relationship with Harry Truman, and so he immediately lost his preeminent position as a close friend and longtime confidant of the president when Roosevelt passed. Truman also had a very high opinion of people such as George Marshall and James Byrnes and he started taking their advice more than Roosevelt did. That being said, Leahy did maintain a good deal of power. After meeting him, Truman decided he wanted to keep Leahy on as his chief of staff, and by 1946 they were even on the road to becoming friends. Leahy, for instance became an automatic companion of the president when Truman started taking his famous vacations at the naval base in Key West, Florida.

The establishment of a strong working relationship with Truman allowed Leahy to keep influence in a few areas—most importantly relations with the Soviet Union. By the time Truman took over, Leahy had met with Stalin twice, at Tehran in 1943 and Yalta in 1945, and had discussed U.S.-Soviet relations with Roosevelt countless times. Though Leahy was never critical of Roosevelt, he was always instinctively more skeptical about the future of relations with the Soviets than the deceased president. He believed a long-term, friendly relationship between the two nations was unlikely and wanted the U.S. to toughen up in its positions—a stance he started urging on the new president.

Truman almost immediately after becoming president asked Leahy for briefings on relations with the Soviet Union. Indeed, the first time Truman met with Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov, he asked Leahy to be in the room with him, providing support. Maybe Leahy’s greatest role in this regard was how he shaped Truman’s most important speech on Soviet relations, his Navy Day address of late 1945 and, even more surprisingly, Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech of 1946. Leahy was the driving force behind the writing of the Navy Day address as a series of points, with a noticeable message about the role of the U.S. in supporting free peoples. When Churchill heard the Navy Day address, he decided to press ahead with an address of his own, which became known as the Iron Curtain speech. Churchill discussed this speech with Leahy more than any other American, indeed they spent one entire morning going through the text when Churchill visited Washington just before it was delivered. Churchill was so grateful for Leahy’s advice that, years afterward, he privately thanked the admiral for it.

Admiral Leahy frequently interacted with many well-known individuals of the WWII era, including those known for their strong personalities such as Admiral Ernest King, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and others. How would you describe Admiral Leahy’s personal style of leadership and management?

Leahy was instinctively political, and this defined his career for either good or ill depending on your point of view. He had the ability to read people and situations and adjust his own responses in such a way to appeal to those with whom he interacted—without revealing his true opinions. His lifelong friend and fellow Admiral Thomas Hart claimed that Leahy was a “born diplomat” who “always gets on with others.” In social situations Hart claimed that Leahy could be as “comfortable as an old shoe.”

This political, personal skill was a powerful weapon in his arsenal. He could use it on people he genuinely liked, such as Franklin Roosevelt, or those of whom he was deeply skeptical, such as Vice President Henry Wallace. It seems from the moment that Leahy met Roosevelt in 1913 he found a way to appeal to the young politician, to behave in such a way that earned Roosevelt’s trust. On the other hand, someone like the left-wing Wallace, about whom Leahy was intensely skeptical, seemed to think that the admiral was a friend or at least thought well of him when that was certainly not the case. Wallace had no idea that Leahy was working to undermine his position when he was Secretary of Commerce under Truman.

Leahy’s political skills were evident in his chairmanship of the joint chiefs of staff and his behavior at the great grand strategic conferences of World War II. As chairman or “senior member,” which was what he normally referred to himself as during the war, Leahy would usually let the other chiefs such as Marshall and King go on at great length with discussing their ideas and plans. If Leahy disagreed he would rarely say so outright, but instead, in a friendly manner, start asking questions of the plan being proposed and in doing so hopefully highlight its weaknesses. Leahy thus retained the impression of being impartial, when at times he was very partial indeed.

When dealing with the higher-ups such as Churchill and Stalin, Leahy normally said as little as possible, and when he did speak it was to support the position of the president. Both Churchill and Stalin eventually understood how much Leahy was valued by Roosevelt and by the end of the war treated him with great respect. Churchill even asked Leahy if the two could establish a private channel of communication, but Leahy, not wanting to do anything that would seem disloyal to Roosevelt, declined.

With the worldview and experience that he held toward the end of his career, how may have Admiral Leahy judged U.S. national security strategy as it stands today?

When Leahy’s career drew to a close in 1948 he was conflicted about the direction of U.S. foreign policy. He has sometimes been inaccurately portrayed as a simple, hardline Cold Warrior. Leahy had a far more nuanced view. He certainly wanted the United States to toughen up its policy vis-a-vis the Soviet Union after the end of World War II, and did not believe the wartime alliance was going to continue. He also wanted the U.S. to support democratic movements around the world—in a mostly non-militarized way.

This points out the big difference between what Leahy believed and how he has been portrayed. While he had no confidence in the future of the U.S.-U.S.S.R. wartime alliance, he was also dead set against the U.S. turning into a world policeman, deploying troops around the world and interfering in the internal affairs of other countries. He was particularly keen to keep the U.S. from becoming an interventionist power in the Middle East. That is why, when President Truman in early 1947 decided to intervene in Greece and Turkey, which is often seen as the start of the Cold War, Leahy was strongly opposed. He tried to change the president’s mind, but to no avail. When Truman decided to press ahead, Leahy, being the presidential servant that he was, publicly supported the move. However, his heart was not in it. Until the end of his time in office he did his best to keep the United States from becoming an interventionist power in the Middle East. He disagreed strongly with Truman over the U.S. decision to recognize Israel for instance, which he believed would lead to decades-long religious war in the region—a war that would eventually drag in the U.S. The differences between Truman and Leahy on the start of the Cold War and the Middle East were one of the reasons for the decline in Leahy’s influence from 1947 onward.

One might describe Leahy’s stance on foreign policy as robust non-interventionism. He was not apologetic about American power or influence, he just did not believe that much could actually be accomplished by interventions in other countries. In that sense, Leahy’s foreign policy vision could very well have resonance today. At the end of World War II the United States dominated world politics. It had half the world’s economic product and its most advanced armed forces. Though it is still the world’s leading power today, it is no longer as dominant as it was then. As such, the country could benefit by rethinking how and where it should involve itself in the world. A Leahy-like policy of greater restraint and less cost could be the natural choice for the U.S.

Phillips Payson O’Brien is a professor of Strategic Studies at the University of St Andrews in Fife, Scotland. Born and raised in Boston, he graduated from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut before working on Wall Street for two years. He earned a PhD in British and American politics and naval policy before being selected as Cambridge University’s Mellon Research Fellow in American History and a Drapers Research Fellow at Pembroke College. Formerly at the University of Glasgow, he moved to St Andrews in 2016.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Content@cimsec.org.

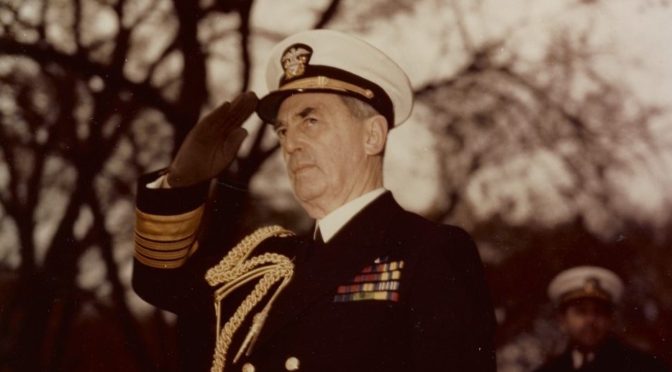

Featured Image: Admiral William Leahy saluting on the reviewing stand during the Navy Day parade, on Constitution Avenue, Washington, D.C., 27 October 1944. (Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives)

“The (U.S.) Navy, on the other hand, sent at least 90 percent of its strength (including one of the largest air forces in the world) to fight Japan. ”

Wow, it’s almost like, I dunno, there was ANOTHER Allied navy, naval air force, and merchant marine available for the Atlantic? Maybe even two, counting the the third strongest Allied Navy?

The insight displayed here… astounding.

Read up on Vice Admiral Allan R. McCann, and the 10th Fleet, and his command and influences. Fully involved in both the Pacific and Atlantic from Pearl Harbor to Hitler’s death, and then Japan’s surrender. Commanded US Forces in Australia. He pulled MacArthur out of the Philippines, was his #2 in Australia. He then moved on to many technical issues, such as torpedo problems, commanded USS Iowa, and the Tenth Fleet, commanded the Potsdam transportation of the President, Arctic explorer, Inventor, directly saved 35 lives of trapped submariners. And likely more. Was USNavy Inspector General. And ComSubPac. And more.

Alright, great interview. I saw the book at Barnes & Noble last week, now I have to buy it, (sigh) Maybe a good companion to “The Admirals.”