James Taylor, Dazzle: Disguise and Deception in War and Art. Naval Institute Press, 2016. 128 pages, $38.00/hardcover.

By Christopher Nelson

There is a fun little ditty in the last page of James Taylor’s book, Dazzle: Disguise and Deception in War and Art. It goes like this:

Captain Schmidt at his periscope,

You need not fall and faint,

For it’s not the vision of drug or dope,

But only the dazzle-paint.

And you’re done, you’re done, my pretty Hun.

You’re done in the big blue eye,

By painter-men with a sense of fun,

And their work has just gone by.

Cheero! A convoy safely by.

British composer George Frederic Norton wrote the tune for a close friend and fellow artist. The friend? His name was Norman Wilkinson. And more than anyone, he was responsible for one of the most iconic painting schemes on ships at sea. Known simply as “Dazzle,” or “Dazzle paint,” it was a mixture of different shapes and colors covering the hull and superstructure of merchants and combatants, primarily in World War I, intended to deceive German submarine captains about a ship’s heading and speed.

Yet years before World War I, Wilkinson established himself as a talented artist. Born into a large family in the late 19th century, in Cambridge, England, he moved to the southern part of the country as a young boy. It was there, in Southsea, England, that his artistic talents flourished. And like many artists, he benefited from the good graces of a well-connected benefactor. In Wilkinson’s case, it was his doctor. But not just any doctor. His doctor was the creator of Sherlock Holmes –Arthur Conan Doyle. The famous author and physician introduced Wilkinson to the publisher of The Idler, a popular British magazine at the time. Wilkinson would go on to create some illustrations for The Idler and Today magazine. These illustrations were the first of many commissioned paintings, drawings, and posters to come. Landscapes, maritime themes, planes and trains, Norman Wilkinson would end up painting them all.

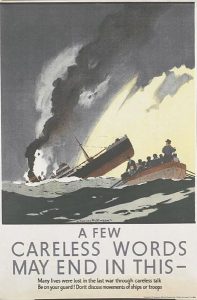

In fact, military naval enthusiasts – and more than a few naval intelligence officers – might be surprised to learn that Wilkinson was later responsible for the World War II poster that depicted a sinking ship with the disclaimer: “A few careless words may end in this.” The poster is obviously a close cousin to the popular American military idiom, “Loose Lips Might Sink Ships,” a piece of operations security art by Seymour R. Goff (who had the interesting nom de guerre “Ess-ar-gee”) that was created for the American War Advertising Council in World War II. Prints of Goff’s work still cover the walls and passageways of U.S. naval shore facilities and ships today.

When World War I began, Wilkinson, like thousands of British men, wanted to join up and, as the saying goes, “do his bit.” Eventually, he was assigned as a naval pay clerk and deployed to the Mediterranean theater in 1915. But by 1917 he was back in Britain, and Germany had resumed unrestricted submarine warfare. It was around this time that Wilkinson had an idea to protect merchant shipping. And as with so many great ideas, often hatched during the quiet, daily moments of life, Dazzle was born, not in a boardroom or on a chalkboard, but in a “cold carriage” following a fishing trip in southern England.

Here Taylor quotes Wilkinson:

“On my way back to Devonport in the early morning, in an extremely cold carriage, I suddenly got the idea that since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer – in other words, to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course which she was heading.”

A few months later, with support from the Royal Academy of Arts, a friend in the Ministry of Shipping, and a few others, the “Dazzle Section” was created. Staffed with artists and modelers (many of them women), they were responsible for paint schemes that covered over 4,000 merchant ships and 400 combatants by the end of the war.

Taylor does a fantastic job at detailing the personalities and the process that got Dazzle from Wilkinson’s mind onto the hulls of so many ships. Taylor discusses the numerous other artists that helped bring Wilkinson’s idea to fruition, the introduction of Dazzle to the U.S. Navy, and its brief return in World War II. He also highlights the dispute between Wilkinson and Sir John Graham Kerr, a professor of zoology at the University of Glasgow who for years claimed that he, not Wilkinson, should deserve credit for the creation of the dazzle concept. Taylor notes that Kerr “relentlessly campaigned to advance his claim that his scheme was in principle one and the same as Wilkinsons.”

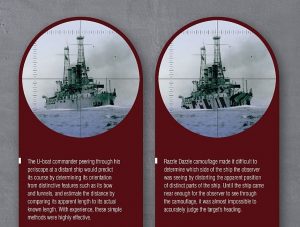

Taylor’s Dazzle, besides succeeding in substance, also succeeds in style. About the size of a composition notebook, Dazzle is large enough to show illustrations of the paint scheme on merchant ships and combatants in clear detail, while it also includes photographs of the artists in the Dazzle sections at work. Hunched over large tables holding small models in their hands, artists carefully painted various Dazzle schemes on each model. Once the model ship was painted they placed it in what they called the “theatre.” This was no more than a room with a table and periscope. The model was placed a circular table and rotated, while another person looked through a periscope that was about seven feet away. “In this way, one could judge the maximum distortion one was trying to achieve in order to upset a submarine Commander’s idea on which the ship was moving.” The colors that covered the model were then meticulously copied onto a color chart that was provided to the contractors who covered the ships in dazzle designs.

Yet the question still remains: Did Dazzle paint work? Did it deceive U-boat commanders? A small painted model in a theatre is one thing, but out at sea is something entirely different.

Unfortunately, as Taylor says, we really don’t know. Dazzle painting was introduced late in the war. Naval critic Archibald Hurd noted that there was not “enough evidence” to determine its “efficiency.” Nor, as Taylor notes, did any captured German submarine captains say that Dazzle confounded their targeting of enemy vessels. A single sentence in a submarine log or captain’s diary –Verdammt die Tarnfarbe! – would be an indictment, but if it exists, it has yet to be discovered by naval historians.

Taylor, the former curator of paintings, drawings, prints and exhibition organizer at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, has written a book that does justice to Wilkinson’s work. The talented Dazzle artists would probably be amazed to see how far his paint scheme has come – as Taylor includes an entire chapter about Dazzle painting’s influence on modern art and how the big blocks of paint now cover cars and even Nike footwear.

My only critique is a request really, that the publishers make this book available in an e-book format for people who prefer the work on an electronic reader.

Regardless, Taylor’s detailed account of Dazzle, his careful selection of photographs, illustrations, and paintings, all printed and bound in a beautiful book is essential for anyone interested in the history of naval deception, World War I navies, or the rare but respected breed who enjoys the intersection of war and art.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson, USN, is stationed at the U.S. Pacific Fleet headquarters in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Navy’s operational planning school, the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island. He is a regular contributor to CIMSEC. The opinions here are his own.

Featured Image: Aquitania in Dazzle Paint/Wikipedia Commons