Charles N. Edel. Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic. Harvard University Press. 392pp. $29.95.

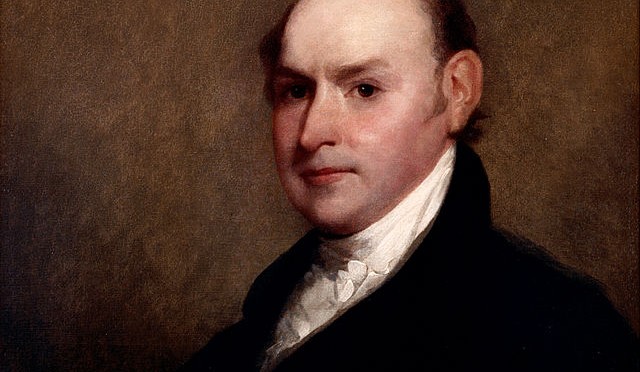

Who knew that John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) was so interesting? Or that he was probably the most sleep deprived and crankiest U.S. President ever to live in the White House? Or that he wrote in a journal every day — totaling some 17,000 pages and 51 volumes — since he was twelve until the day he died on the floor of Congress in 1848?

The word “fascinating” doesn’t begin to describe this man. But unfortunately for John Quincy Adams, his father has seemed to eclipse him in many ways. David McCullough’s wonderful biography of John Adams, which was turned into a popular HBO series, cemented the founding father’s stature in the collective American conscience. Thus, many of us only know John Quincy as a sequel, a trivial pursuit question: “Which eighteenth-century U.S. President had a son who also became a U.S. President?” It is always, it seems, this way with sequels. They never quite measure up in our minds and in our hearts.

Yet recently, it looks like John Quincy is getting his due. In May of last year, Fred Kaplan released his biography of the sixth President of the United States, titled, John Quincy Adams: American Visionary, to a warm reception. And just this past January, Phyllis Lee Levin’s book, The Remarkable Education of John Quincy Adams, hit the shelves. Call it a John Quincy revival. Still, there is always room on the bookshelf for another well-written book on this overlooked and under-appreciated president. Enter historian and U.S. Naval War College professor Charles Edel’s excellent new book, Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic.

Edel’s book is not a biography per se, and nor is it a book about John Quincy’s character, his life and times, or a detailed discussion of his policies. Rather, Edel sets out and argues, and quite convincingly I might add, that John Quincy was a grand strategist — maybe America’s first. That is, he not only defined clear objectives for the United States, but he was also, as Edel says, able to leverage all the instruments of national power — military, economic, diplomatic, and moral — to ensure the future security and prosperity of the American people.

Edel begins his book with John Quincy’s formative years, traveling with his father (crossing the Atlantic during the Revolutionary War and barely evading capture by the British), dining with Jefferson, reading (his father insisted on Thucydides), writing, and learning languages — French, German, and Dutch, to name just a few — that he would eventually use as a teenage diplomat in Europe. It is in those early years where we see that John Quincy, through diligent study and the puritan ethic of public service before personal happiness, made himself.

The book is then divided into chapters that trace the highlights of his extraordinary career: his challenges with depression and seeking purpose in the late 1790s; his involvement in American diplomacy and his rise in politics in the early 1800s; his ideas and debates on territorial expansion and the Monroe Doctrine, and finally, the “slavery question.” Throughout all of this, though, John Quincy retains his priorities and his national objectives. Adams, Edel tells us, understands that for the U.S. to become a strong nation, we must expand our territory, increase our national resources, remain neutral in European affairs, and build up our defense forces to ensure that other countries — notably France and Britain — did not try to fracture American solidarity. These principles, these objectives, would remain in the forefront of Adams’s mind throughout his life.

As secretary of state under President James Monroe, Adams was responsible for negotiating the Adams-Onís treaty, thus giving Florida to the United States — in return the U.S. settled a border dispute with Spain along what is today areas of the Sabine river in Texas. Adams also wrote the Monroe Doctrine — a seminal document in American history that, in simple language, told all European powers (and others) stay out of our business.

Interestingly, John Quincy would be most remembered in his twilight years. The first (and only) U.S. President to be elected to the House of Representatives after leaving office. He famously argued a case in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, United States v. Libellants and Claimants of the Schooner Amistad. He won the case, successfully arguing that the Africans aboard that ship should be set free. But while Edel reminds us that John Quincy detested slavery, John Quincy was averse to critiquing slavery publicly, in fear of tearing the nation apart. While he would always, it seems, nip at the edges. For example, trying to find ingenious ways to get around the “gag rule” that barred discussions of slavery on the floor of Congress.

John Quincy’s path to American prosperity and security was not without stumbles. Edel says that, “Adams grand strategy included a clear vision of where the country needed to go and a detailed policy road map for how to get there. But in many instances he lacked the ability to convert that vision into political reality.” For instance, Adams tried, but failed to get enough votes for the creation of a U.S. Naval Academy. Legislators thought that it would cost too much, and “critics…argued that federal appointments to such an academy would become ‘a vast source of promotion and patronage’ which would invariably lead to ‘degeneracy and corruption of the public morality.'”

John Quincy was an impressive diplomat and intellectual giant, but he was also a conflicted man, a contrarian, and, in all honesty, not someone who you would want at your dinner table. As Edel says, “Adams was certainly most comfortable when he stood in opposition to something or someone. Intellectual and industrious, rigid in his beliefs, and with a propensity to see issues and people in stark terms, in many ways Adams was an odd fit for politics.” The Sage of Concord, Ralph Waldo Emerson, whom Edel quotes, also had a few choice words for John Quincy, saying:

He’s no literary old gentleman, but a bruiser and loves the melee…[he] must have sulfuric acid in his tea.”

Adams, then, did not suffer fools.

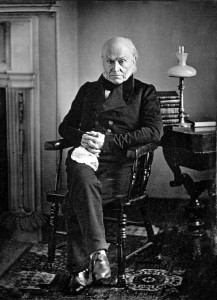

This is probably most easily seen in what is believed to be the first photograph ever taken of a living U.S. President. In 1843 Phillip Haas took a picture of the former president, who was then 76 years old. He is seen sitting, legs crossed, hands clasped, and head slightly down. His lips are pursed and he has an expression of impatience or frustration.

In a recent interview with Edel, I asked him this question: “Do you think he was ever satisfied with is life?”

Edel said:

“…[A]t many points in his life he refers to himself as a Job like figure. In many ways, he sees his job as one of persistence and endurance. If he thinks about his policies, how his plans have gone awry, how others have distorted his policies, then he is rather less pleased with the result. But he’s not really someone who is satisfied – ever.”

There is only one small quibble I have with the book. At one or two points Edel repeats an idea within a chapter, or uses the same quote twice, making you pause for a moment in a sense of déjà vu, wondering if you had or had not just seen the same words pages prior. But again, this is a minor point. Overall, this is an excellent book. And whether you are new to John Quincy Adams or if you’ve read most of the current literature on this man and his presidency, I promise you’ll learn something new and interesting in these pages.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson, USN, is a career intelligence officer and recent graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Navy’s operational planning school, the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, RI. LCDR Nelson is also CIMSEC’s book review editor and is looking for readers interested in reviewing books for CIMSEC. You can contact him at cimsecbooks@gmail.com. The views and opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Navy or the Department of Defense.