Is There a Class of Armored Cruisers in the U.S. Navy’s Future?

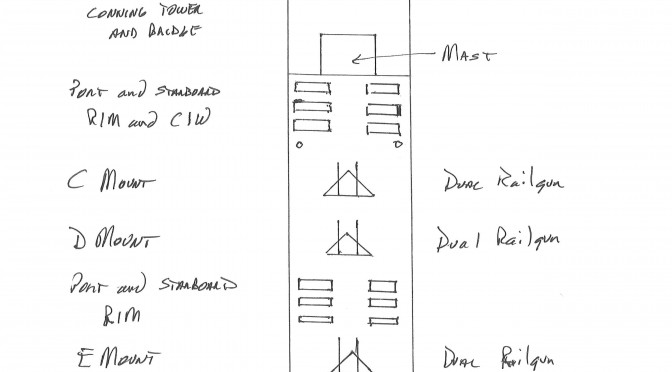

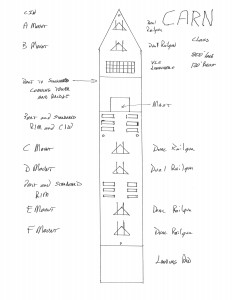

Sketch by Jan Musil. Hand drawn on quarter-inch graph paper. Each square equals twenty by twenty feet.

This article, the fourth of the series, presents a suggestion on how to incorporate the new railgun technology into the fleet in an efficient and effective manner. Railguns, when used as a complement to the various UAVs, UUVs and Fire Scouts discussed earlier will provide the fleet with a potent AAW weapon. Read Part One, Part Two, Part Three.

Interestingly enough, the most important piece of information concerning the new railgun is a number. A single round of ammunition costs $10,000. Eighteen inches of railroad tie shaped steel (which costs less than $200) fitted with the wonders of modern microelectronics provides a startling contrast with the $1M+ cost of the missiles the Navy currently uses against incoming aircraft and missiles. A contrast that is even more in the Navy’s favor since any future opponent will be spending comparable sums for their attack missiles and substantially more for hypersonic cruise missiles.

There are no explosives purchased with the $10,000. This means hundreds of rounds of railroad ties and microelectronics can be safely stored in a ship’s magazine. This is a substantial advantage compared to the VLS missiles in current use by navies around the globe, most of which require specialized loading facilities to reload their missile tubes. In contrast, a railgun-equipped ship can take a much larger ammunition load to sea with it, and reload the magazine at sea if necessary.

The next relevant parameter of the new railgun is its range. At 65 miles this is far less than many long-range missiles, though still quite useful against incoming aircraft and missiles. Note that with an ISR drone or Hawkeye providing over-the-horizon targeting information, a surface ship equipped with a railgun can shoot down incoming aircraft such as the Russian Bear (Tu-95) reconnaissance aircraft before the intruder can lock in on the firing ship. The same is true for any attacking aircraft carrying long-range strike missiles.

This highlights the importance to both sides of providing accurate targeting information first. It also means, strategically, at its heart the railgun in the 21st century maritime environment is a defensive weapon: well positioned to provide defensive fire against incoming attacks, but with an offensive punch limited to sixty-five miles.

That said, with the ability to fire every five seconds the railgun can be very effective, particularly when utilized in quantity when escorting carrier strike groups or when placed between a hostile shore and an ARG.

So far we have noted the positive distinguishing capabilities of the railgun but there are three significant difficulties that come with fielding the weapon. Foremost is the enormous amount of electrical power discharged by the gun when firing. This means any ship equipped with a railgun needs substantial electric power generating capabilities, something certainly beyond the abilities of the DDGs and CCGs currently in the fleet.

Secondly, using these vast amounts of electricity means a large capacitor needs to be located on the deck below the railgun. Large does mean large in this application. No little white pieces of ceramic plugged into a circuit board will do here. The necessary equipment is physically massive and in need of protection from the elements. They will be taking up a substantial amount of space just below the main deck where the railgun has to be mounted, probably one per gun.

The third problem is that all the energy dissipated in launching a round generates heat. Lots and lots of it. Most, but not all, of the energy used to launch the eighteen inches of steel will be recovered back into the ships capacitor, but enough will be lost that the launching rails flexing as the railgun is fired simply must be exposed to the elements so the heat will dissipate in the air. No sailors or flammables nearby please.

The inevitable follow up conclusion means a railgun equipped ship is going to be impossible to hide from opponent’s infrared sensors. Regardless of how stealthy versus radar the ship is, all of that heat is going to stand out like the sun itself to incoming aircraft and missiles equipped with infrared targeting systems, which means it is almost a certainty the firing ship is going to get hit if subjected to a seriously prosecuted attack.

Armor

This ship is not going to be able to hide in a cloud of chaff, it will be heading into the incoming missile strike, placing its full broadside in a position to fire and it will be considered a high priority target.

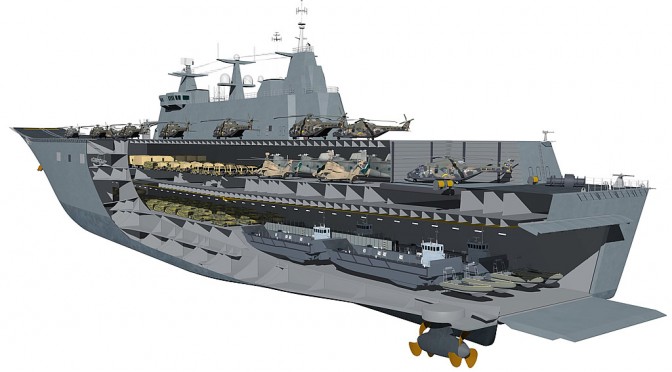

Unlike almost all naval ships built across the globe since the end of WW2, this class needs to be built with the assumption that incoming missiles will hit it, the plural is intentional, and be able to survive the multiple collections of missile slag and burning fuel and the occasional warhead detonation. Just as we built the 44 gun class of frigates back in the 1780s to be thick hulled in order to survive the gunnery practices of the time, armored up the ironclads of the Civil War and multiple classes of ships intended for the main battle line of the last half of the 19th Century and first half of the 20th Century, we need to built this class to ‘take a licking and keep on ticking’.

Topside armor should cover most of the ship, but the prime purpose of this armor will be to shed missile slag, i.e. what is left of the incoming missile after being intercepted and its fuel. The impact of the metal missile parts is not the prime danger to be protected against here. It is the fuel, and the accompanying fires after impact that is the true danger. So the topside armor needs to keep the slag and fuel on the outside of the ship, hopefully allowing gravity to carry much of the burning fuel to the gunnels and overboard; in the process vastly easing the firefighting teams job in putting out any fires that have started.

Additional armor, probably using a combination of layered materials and empty space, is appropriate for selected topside compartments that need to be protected against a successful missile warhead detonation. Whether it is sailors or equipment that is being protected, only some compartments will need beefed up exterior armor.

After that the CARN (cruiser gun armor, nuclear powered) will need to adapt the principles of the ‘armored citadel’ concepts developed a century ago for battleships to the needs of securing the two, possibly three, nuclear reactors aboard and their associated pumps and other equipment. Whether this is best done with one internal armor layer or two will keep the engineers debating for quite a while as the CARN is designed.

CARN Equipment

So what should the new 25k+ ton armored cruiser have aboard? Nuclear propulsion is an unavoidable necessity given the enormous amounts of power each railgun requires; every five seconds when engaged. Since the primary use of the CARN will be to accompany the fleet’s carriers to provide defensive AAW capabilities, this is actually an advantage for both strategic and tactical reasons. Depending on the amount of power twelve railguns firing broadsides will require, two or three of the standardized nuclear plants being installed in the new carriers should work just fine.

Lots of armor and nuclear power are unavoidable. The following basic list of desired equipment should provide the reader with a good idea of what the CARN should go to sea with.

12 railguns mounted in six dual mounts. In the attached sketch A and B mounts are placed forward of the bridge while C, D, E and F mounts are located starting roughly amidships and extend back to the helicopter deck. Dual mounts are suggested since the large size of the capacitors that need to be located directly below each railgun will in practice utilize the full 120 feet of beam provided. Obviously if the capacitors are even larger than this, then single mounts will have to be employed. Let’s hope not as doubling up makes for a much more efficient ship class.

36 VLS tubes capable of a varying load out of ASW, SM-2, SM-6 and long-range strike missiles as the mission at hand calls for.

4 CIWS with one located in the bow, a pair port and starboard amidships and one aft, just behind F mount.

12 rolling missile launchers for close in defense. It will be no secret the CARN is in the task force so a substantial number of the incoming missiles will be using infrared targeting, either in place of, or as a supplement to radar. So adding half dozen rolling missile packs to port and another half a dozen to starboard will provide plenty of localized missile defenses for both the CARN and the task force as whole.

2 ISR drones if VTOL capable. None if VTOL capability is not available

2 Seahawk helicopters

This suggested list very deliberately reduces the VLS and ASW capabilities aboard to a bare minimum. Good ship design concentrates on the primary mission the class needs to accomplish. In the case of the CARN that is absolutely, positively AAW.

In the next article we will examine how adding UAVs, UUVs, Fire Scouts, buoys and railguns in quantity to the fleet can substantially enhance the Navy’s ability to survive in the increasingly hostile A2AD world of the 21st Century. Read Part Five here.

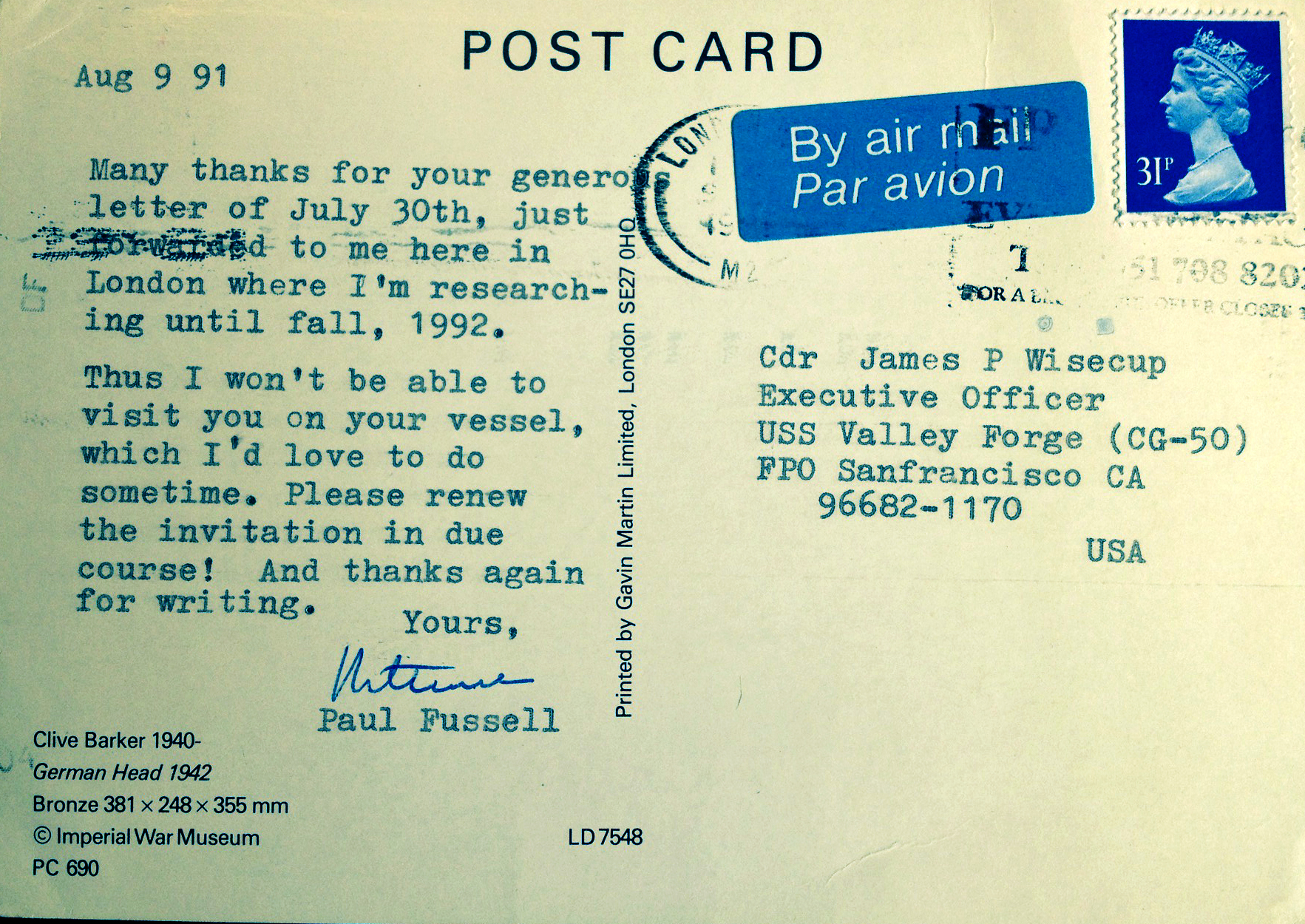

Jan Musil is a Vietnam era Navy veteran, disenchanted ex-corporate middle manager and long time entrepreneur currently working as an author of science fiction novels. He is also a long-standing student of navies in general, post-1930 ship construction thinking, design hopes versus actual results and fleet composition debates of the twentieth century.