By C. Travis Reese

“Any military activities that do not contribute to the conduct of a present war are justifiable only if they contribute to preparedness for a possible future one.” MCDP-1 Warfighting

Defense of the nation is a never-ending task. It is achieved by balancing readiness for today’s threats and tomorrow’s challenges. The relationship between current and future readiness is not a clean demarcation but a part of a continuum. Yet, when it comes to having a prepared force, the ambiguity around how the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) defines readiness is muddying the prioritization between current threats and future modernization efforts. Actions in Ukraine are reinvigorating how DoD leaders evaluate preparedness for conflict. This makes the current era as important a time as any to understand how to assess overall readiness and the requirements to manage risk as the force prepares to address a peer adversary.

What would a better method of defining institutional readiness look like? In a nutshell, it would require DoD to establish an easily understood criteria for institutional readiness. This will allow co-equal comparison between the current and future to manage the risk between investment and divestment as it applies to the transition between the “as is” force and the future “to be” force. Why? Because as the character of war inevitably evolves it is necessary to know and develop those first principles of readiness that enable DoD to succinctly identify needed changes. This must be done in advance of when those changes may seem likely so that the wrong force is not maintained beyond its absolute utility and the current force is not undermined in its preparedness when disruption is not needed.

Readiness is the purpose behind the process

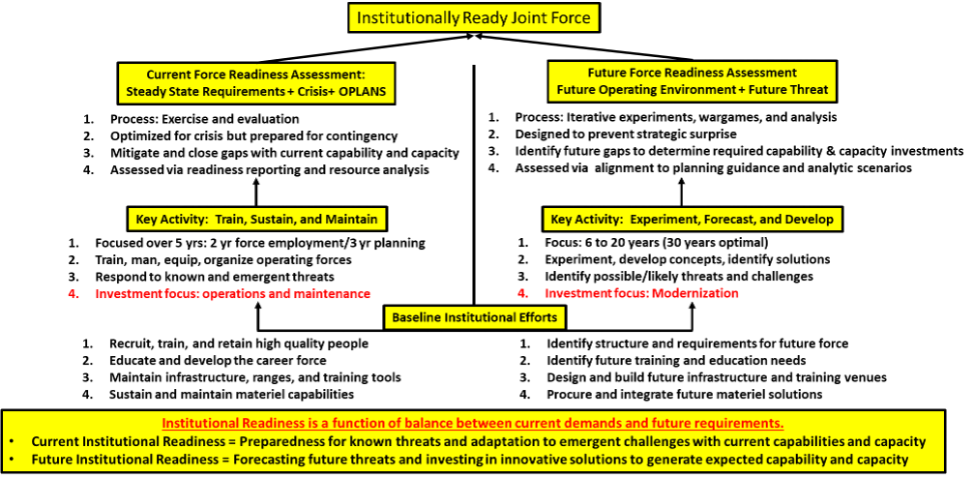

The core concern of DoD leaders is the readiness of the force, both for current and future challenges. Talk of concepts, manpower, capability, acquisition, forward basing, etc. are attributes and features of one great concern: readiness. There is no common definition of readiness across DoD, but there are some frameworks to help understand the components of current readiness and generating future readiness. The Components of Institutional Readiness diagram provides one example:

Components of Institutional Readiness

Current readiness is enabled and assessed through the items on the left side of the chart and focused principally within the 5 year time frame of the current Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) (or military budget to the laymen). It is actual and real, not conceptual for which existing assets are committed as determined in the global force management and annual joint assessment process as key activities. It is the writ of commanders (both providers and employers) to assess their forces and identify gaps in capability and capacity based on existing theater Operations Plans (OPLANS). OPLANS are approved through the appropriate chain of command from Combatant Commanders to the Secretary of Defense and clearly identify the approach to engage current threats. They are evaluated through exercises and war games that test and revise the plan to maintain pace with an adversary and not a “past tense” frame of the problem or mission. These are “fight tonight” operations that current forces train to accomplish.

Future readiness is created through the components on the right side. It is largely conceptual in nature and framed through approved scenarios that represent plausible interpretations of future events relative to likely threats. Scenarios are evaluated through a qualitative wargaming process testing concepts, policies, or decisions or a quantitative process of modeling and simulation objectively replicating the environment with testable and repeatable variables and conditions. Both analytic methods when filtered through a net assessment enable discovery of gaps that may impact the future readiness of the force to succeed against future threats. War games and experimentation are used to examine the hypothesis of the future operating environment proposed in the scenarios and evaluate attributes of potential solutions. The results then are extrapolated to the requirements that inform the development of future concepts and their supporting capabilities.

The Iron Triangle of Capabilities, Threats, and Resources

The sustainment of the “as is” force and the creation of the “to be” force is framed by the balance of capabilities, threats, and resources. Different entities within DoD, based on their responsibilities, usually adopt one of the variables as their dominant lens and position. Those viewpoints are not, nor should they be, exclusive since they must be informed by inputs from the other two variables to have any context or meaning at all. Building a thing for a thing’s sake with no appreciation of why or with how much is anathema in any sense, let alone for a military application. Typically, in DoD capabilities are the lens of Services as force developers and force providers. Threats are the focus of the combatant commands as well as the Intelligence Community. Resources (especially money) are the dominant viewpoint of the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Staff given their statutory duties in that regard. There are nuances within that, but that is the organized tension within DoD, which, when managed in collaboration vice competition can be highly effective.

To reconcile those points of view as they apply to future force design, a scenario-based analysis through wargaming or simulation is conducted. The scenario does not dictate the outcome but rather fuels the context to identify the balance between the three variables. Truly useful scenarios are agnostic of solution but present the plausible framework to consider problems and identify the attributes of potential solutions usually within a given timeframe of consideration. Good scenarios allow the introduction of any range of options or approaches. Scenarios for any military context should look and feel like military plans and orders. This realism helps to distinguish the difference between using current means and practices or adopting future ones. Scenarios must be accompanied with a thorough explanation of the factors and ideas that form their creations so they can be modified as needed with new data or plausible projections. Managed iterations of scenarios help to show an evolution of thinking and learning about future problems.

Scenarios that are suitable for wargames at the Department-level to identify future gaps and challenges are the result of interactions among three entities. The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy provides an understanding of the desired “ends” from the National Defense Strategy (NDS) with amplifying detail through the defense planning guidance and framework defense planning scenarios. The Services with interaction from the Joint Staff create a model of the Joint Force applied to the scenarios, giving structure to the potential “ways” of the NDS. This comes in the form of Joint Force Operating Scenarios (JFOS). The JFOS mimics a Level 3 Operation Plan (OPLAN) set in a future operating environment. The Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD(CAPE)) and Service’s programming and budget evaluation offices examine the potential solutions necessary to achieve the ways and provide comparative assessment of the “means” presented by the Services to recommend the best composition for the force. The work of CAPE and other service analytic organizations is generally performed through quantitative modeling and simulation derived from the conditions applied to scenarios and war games. Only one product, the Joint Operating Environment (JOE), produced by the Joint Staff J7 routinely attempts to articulate a plausible future out to twenty years. The JOE is not comprised of any specific scenario but more a well-considered primer of issues influencing future security considerations.

The case for modernization is derived from the results of wargames and analyses from the scenarios and impacts the ability of the Service chiefs to design and fund the needs for the next evolution in the character of conflict. The case for maintaining the current force is based on current threats and emergent conditions which impact the ability of Combatant Commanders to fulfill their approved plans and missions. Suffice to say, there is no substitute for thinking hard about a problem which often corresponds to buying institutional time to think long as well. Planning earlier and including the potential growth in adversary capacity facilitates delivery of capabilities at the time they are needed, not after. Further, it can prevent retaining something long after it is useful, which causes current gaps to become more urgent and draws institutional focus to the present at the expense of the future. There is also a tendency at times to consider readiness by covering as many options through sub-specialization and regionalization in force development. That can provide useful insights, but in general those should be unique exceptions needed for a particular challenge balanced by the general demands of the force with tools that are applicable and adaptable to nearly any circumstance.

Assessing Risk between current and future

Understanding how institutional readiness is derived must be synchronized with a method for weighing risk against current and future threats. Much ink and rhetoric has been expended to complain over who has the best view and need to lead the efforts of force design in DoD. Secretary of Defense staff? Joint Staff? Combatant Commanders? Service Chiefs? A simple answer is “yes”, and it depends on what is being measured. Quite clearly Combatant Commanders come with a regional and threat-specific focus gauged on the near-term. That would make it inappropriate for them to manage efforts and Service-level resources to design a force that requires 10 years on average just to identify and develop. Further, Combatant Commanders compete against each other for resources and do not have a unitary appreciation of the threats. Yet they are totally within their purview to request forces with capabilities that make it possible to achieve assigned missions, and modify those forces as needed to suit the task. Conversely, the Service Secretaries and Chiefs must adjudicate that world-wide view and create forces capable of operating in any climb and place. They must deliver capabilities that require alignment of entire enterprises in complex discovery regardless of how often priorities shift or misguided defense acquisition efforts can be. This can be a complex process which requires OSD, with the aid of the Joint Staff, to provide an objective assessment of the proposed solutions to current and future readiness by the Combatant Commanders and the Services.

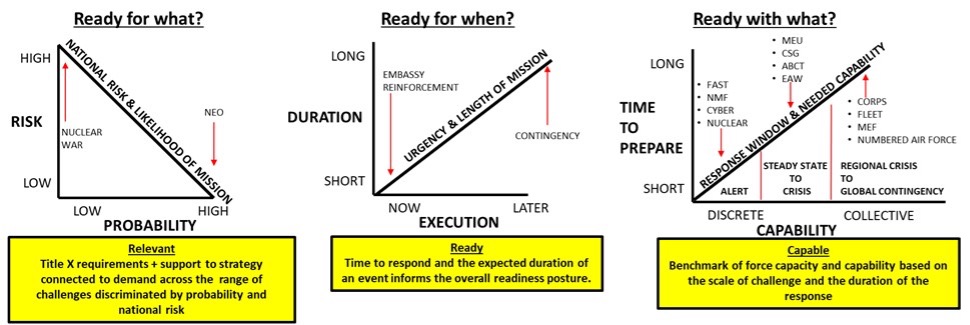

Richard Betts’ 1995 book Military Readiness: Concepts, Choices, Consequences, articulated a framework for thinking about readiness where he argued that decision-makers need to ask three key questions about readiness: Ready for what? Ready for when? And Ready with what? How can Betts’ framework be converted into a common model of comparison between current and future to co-equally weigh the sustainment of the current force against the imperative to modernize? An example is below:

Risk Framework for Capability and Capacity

This model takes the three questions posed by Betts and frames them in three different graphs to help visualize risk and assess value based on the interactive variables of mission relevance, readiness to conduct a mission, and the capability of various force options. The graph under “Ready for What?” shows risk in terms of a military problem based on the likely frequency of occurrence. For example, nuclear forces may rest on the highest risk challenge with the lowest likelihood of occurrence. They are relevant to strategic deterrence but may have limited value in terms of day-to-day competitive activities. This graph also shows that generally lower risk activities (that can be cumulatively consequential to national security) have a higher probability of occurrence opposed to existential concerns. This gives a scale of an investment’s value based on its use case and the risk of not having it poses to our nation and our interests. The graph in Ready for when? shows how the duration of an expected challenge and how quickly it must be responded to factors into the cost of sustained preparedness. An immediate response requirement (ex. hostage rescue) requires a persistent ready posture. This may be opposed to larger scale contingencies that historically have longer periods of indication and warning with corresponding windows in time to prepare. The graph shows how overall daily readiness and training requirements factor into cost and sustainment of unique capabilities. Lastly, under “Ready with what?,” risk can be evaluated in terms what type of force is required for a challenge (large or small) and how long that force will be used. Generally, a short duration mission requires a discrete force of specialized capability, and a longer mission requires a larger force but that will take longer to prepare and enable. That will reflect on the capability of a force to operate effectively and how much investment is required to reach the standard necessary for a planned contingency.

The effectiveness of this model is a function on two factors. First, it converts Betts’ framework into a formula that can be applied to readiness for both current and future challenges to provide co-equal metrics of comparison. Second, it provides a clear criteria and visualization for the significance of those criteria by assessing the risk of maintaining a current capability or necessity of transitioning to a future one. Regardless of the choice, Betts’ framework can help move the Department forward when it comes to weighing risk with more empirical values that balance subjective and objective concerns in current force employment and future force design.

Conclusion

The DoD has struggled to define institutional readiness and find a risk framework that can be equally applied to future and current concerns. Bett’s framework and other models in this discussion are templates for conducting comparative analysis of current and future risk to identify which focus areas are of primary concern. The framework used for distillation of those focus areas will inform the investment balance and mitigate tension between current urgent and future important concerns. This competition is framed by an acceptable risk level tolerance competition, pitting current and future challenges against each other. If a current challenge is unmitigated and high risk, it may require DoD to de-emphasize evaluation of future objectives. If the future appears to be riskier and the current challenges are as “in hand” as they will ever be, then an emphasis on addressing future concerns would be required. Currently, the DoD does not compare current and future threats to a common framework. The lack of framework creates an inability to weigh efforts and resources for either near term security or long-term effect or to even make an assessment. Instead, they are lumped into a pot of “threats” and sorted out by the whomever is the most successful advocate posturing around a vague definition of the need to be “ready” with very few metrics of prioritization or categorization. The goal of readiness is to avoid “present shock” – a condition in which “we live in a continuous, always-on ‘now’” and lose the sense of long-term direction. This can only be achieved when readiness is clearly defined with common criteria for evaluating the risks of sustainment and modernization of capabilities as they apply to current problems or future dilemmas.

Travis Reese retired from the Marine Corps as Lieutenant Colonel after nearly 21 years of service. While on active duty he served in a variety of billets including tours in capabilities development, future scenario design, and institutional strategy. Mr. Reese is now the Director of Wargaming and Net Assessment for Troika Solutions in Reston, VA.

Featured Image: EIELSON AIR FORCE BASE, Alaska (March 25, 2022) – A formation of 42 F-35A Lightning IIs during a routine readiness exercise at Eielson Air Force Base (EAFB), Alaska, March 25, 2022. The formation demonstrated the 354th Fighter Wing’s (FW) ability to rapidly mobilize fifth-generation aircraft in arctic conditions. (U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Jose Miguel T. Tamondong)

I do not think we are ready war, or the civil war that.is looming in the USA