By Jason Lancaster

Russian forces crossed the border into Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Since then, these forces have been slowly advancing;1 yet there has been little press coverage of activity at sea. The Russian Federation Navy has exercised sea control throughout the conflict, which it has so far exploited to conduct an amphibious landing near Mariupol,2 attack merchant ships with missiles, and bombard Snake Island. It remains unclear whether Ukraine or Russia are responsible for drifting mines discovered in the Black Sea and neutralized by Turkey and Romania.

Prior to hostilities, Russia transferred several ships from the North and Baltic Sea Fleets into the Black Sea, including a Slava-class cruiser and six Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs).3 Since hostilities began, Turkey has closed the Bosporus Strait to all warships, eliminating Russia’s ability to reinforce the Black Sea Fleet.4

Maritime strategist Julian Corbett divided the concept of sea control between local or general, temporary or permanent. Sea control means controlling the sea lines of communications one side needs to maintain while fighting to deny that control to an adversary. Wayne Hughes described sea denial as “turning the ocean into a vast no man’s land.”5 Ukraine lost 80% of its navy and support infrastructure with the loss of the Crimea in 2014.6 With little money, few ships, and no time to acquire new weapons, Ukraine cannot achieve sea control. However, the right NATO support could enable Ukraine to deny Russia sea control, limit Russian maneuver, and impose costs on the Russian Federation Navy.

To deny sea control to the Russians, Ukraine needs sea mines, coastal defense cruise missiles, and scouting assets, such as fast patrol boats and drones. These systems have a symbiotic relationship in layered defense. Mines slow down the adversary; during clearance operations, CDCMs have an opportunity to engage the slowed vessels; and scouting assets support maritime domain awareness for over the horizon targeting. NATO should rush these weapons to support Ukraine’s defense.

Sea Mines

“We have lost command of the sea to a nation without a navy, using weapons that were obsolete in World War I and laid by vessels that were used at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ.”— Rear Adm. Smith, Commander, Amphibious Task Force, Wonsan, Korea, 1950.7

Any coastal nation can utilize mines to defend its coast. Mines are a cheap and effective way to deny the enemy maneuver. Mines damaged more U.S. ships since the end of World War II than any other weapon. They can be effective and terrifying. The majority of the Black Sea between Odessa and Crimea is less than 50 fathoms, which makes it an excellent location for mine warfare.

Location in the water column and fuse systems are the two ways mines are classified. Protective and defensive mining defends one’s own ports in territorial and international waters. Protective minefields would help defend the Ukrainian army’s flank from an amphibious assault. Offensive mining denies the enemy the use of their ports or closes off chokepoints. Floating mines are in violation of the 1907 San Remo Treaty but have been found in the Black Sea. It is unclear whether they were Ukrainian or Russian mines that broke free of moorings, or if they were part of a Russian false flag operation.8

Offensive minefields laid off of the main naval base of Sevastapol and in the Kerch Strait would limit the Russian Navy’s ability to maneuver and operate in the Black Sea. The majority of Russian ships in the Black Sea are smaller ships, such as frigates and corvettes. Smaller ships require more frequent port visits to resupply and give their smaller crews time to rest. Closing off the port of Sevastapol and the Kerch Strait would prevent the ships from resupply or leaving port.

NATO partners such as Italy are world leaders in mine development. The Italian Manta mine is a popular bottom influence mine. A Manta mine damaged the USS Princeton (CG 59) during the first Gulf War. NATO support to Ukraine has included other defensive weapons, such as anti-aircraft missiles and anti-tank weapons; mines would be an effective way to defend Odessa’s right flank while denying the Russian Federation Navy control of the Black Sea.

Coastal Defense Cruise Missiles

“They blew my old ship Sheffield away last night…” —Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward RN, Commander Falklands Battle Group, 19819

The first battle with anti-ship cruise missiles occurred in 1967. Egyptian patrol boats sank the Israeli destroyer Eilat with Styx missiles. The British lost several ships to anti-ship cruise missiles during the Falklands War. An Exocet fired from the beach damaged HMS Glamorgan. The Argentinians used ship-based missiles jury-rigged to fire from a truck. Both of these examples demonstrate a naval David’s challenge to a naval Goliath.

Without missile-armed ships or aircraft, coastal defense cruise missiles (CDCMs) are the main way Ukraine can challenge Russia’s sea control. CDCMs mounted on transport, erector, launchers (TELs) are highly mobile. They identify a target, shoot, and then maneuver to another location. The threat of missiles changes operational behavior. Most modern navies draw range rings around the coast of an opponent with CDCMs. Within the enemy’s weapons engagement zone (WEZ), ships will operate in ways to minimize the risk of detection and maximize their chances to defend themselves. These behavioral changes limit Russia’s ability to utilize their fleet to their advantage. The added stress of sudden combat increases fatigue and can lead to mistakes.

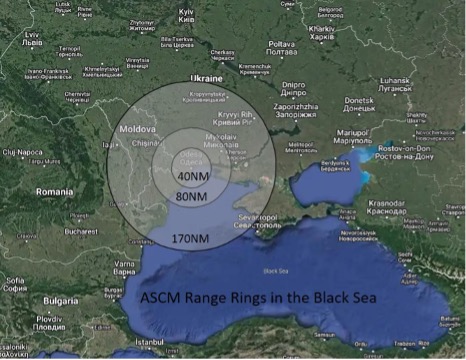

Many countries including Ukraine produce anti-ship cruise missiles. Ukraine produces the RK-360 Neptune anti-ship cruise missile. The Neptune is a derivative of the SS-N-25 Switchblade, also known as the “Harpoonski,” which supposedly became operational in 2021.10 It has an operational range of about 170NM. Most of the Black Sea Fleet is vulnerable to the Neptune, which is capable of sinking ships up to 5,000 tons. Despite the missile being in service, there have been no media reports of its use in the war.

NATO nations should rush to send Harpoon and Exocet missiles and surface radars to Ukraine to support targeting Russian ships. Depending on variants, these missiles have ranges of about 40-80NM. Missiles with those ranges will enable Ukraine to deny sea control near Odessa.

Scouting Assets

Scouting and anti-scouting are key elements of naval warfare. Without scouting, one cannot effectively target the enemy. Conversely, anti-scouting shields your own force from detection. Modern scouting and anti-scouting are multi-domain: cyber, electronic warfare, radar, ships, subs, and aircraft. Captain Hughes defined the role of scouting as “to help get weapons within range and aim them effectively.”11

Missiles need targeting data. Radars are the most effective way to surveil large quantities of ocean, but they lack the ability to classify a target. Classification requires a visual sighting of the ship or electronic reconnaissance. Electronic reconnaissance is passive and detects radar emissions from ships and aircraft. Combinations of different radars can help classify ships.

Ukraine procured several scouting assets before the war began, two of which were the Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) and the U.S.-made MK VI patrol boat. Ukraine started the war with an unclear number of TB2s, possibly between 12 and 36. These UAVs have a 27-hour endurance, 186-mile range, and carry four laser-guided munitions. UAVs endurance and armament enable them to function as scouts in the narrow confines of the Black Sea. UAVs can identify targets in conjunction with radar and electronic warfare assets, minimizing the risk of sinking neutral shipping with ASCMs. Not only can TB2s scout, they can also attack. Their guided munitions can damage radar and communication antennas, putting modern ships out of action.

The United States had a foreign military sales agreement with Ukraine for 16 MK VI patrol boats, 3 of which were scheduled for delivery in 2022. These 25-meter patrol boats are equipped with two remote-controlled 25mm guns. With a 600NM range and a speed of 45 knots, these boats could use speed, darkness, and littoral clutter to scout.12 In addition to scouting duties, these boats could be used in anti-scouting and offensive roles.

Since the development of the torpedo in the 1880s, small boats with torpedoes and later missiles have been able to challenge larger warships. These boats are fast and can undertake offensive action in the Black Sea littorals to disrupt Russian actions and impose costs. They are not designed to carry mines, but they can carry a 7-meter rigid hull inflatable boat (RHIB) in an angled stern ramp. Removal of the RHIB would free ramp space to carry and launch mines. Their range and speed allow them to travel the 158NM from Odessa to Sevastopol, mine the harbor, and utilize LAWs, Javelins, and other small missiles to disrupt Russian operations.

Conclusion

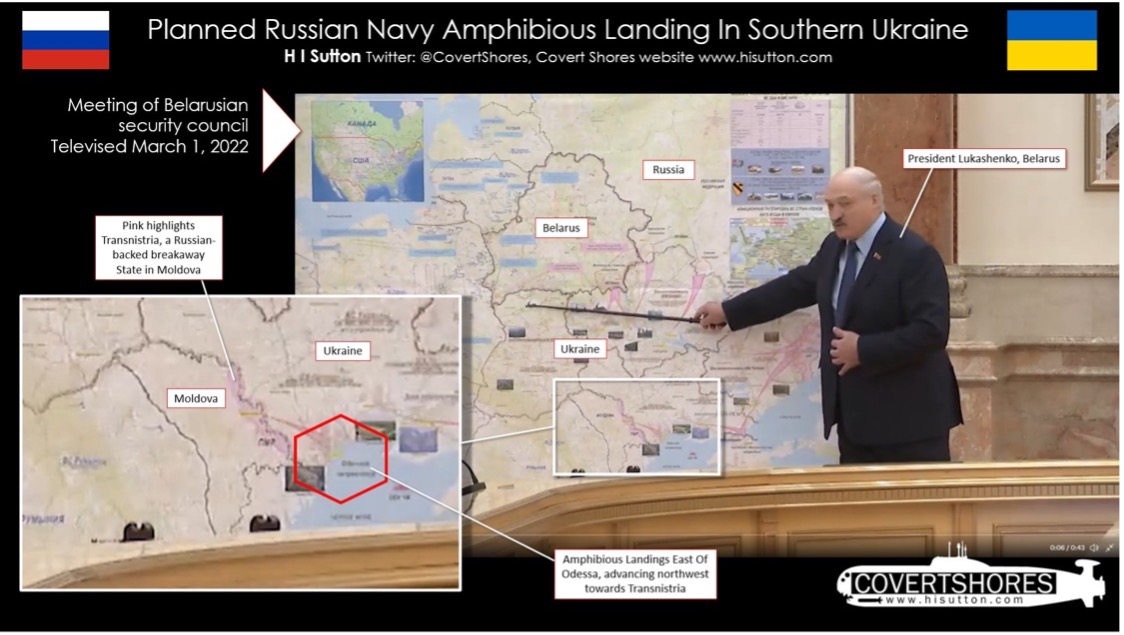

Russia has not yet moved amphibious forces towards Odessa, but it is likely they will in the future.13 President Lukashenko was photographed in early March with a map showing a planned landing to the east of Odessa. The assistance recommended in this article would help Ukraine challenge the Russians and allow them to contest control of the Black Sea.

Without assistance, Russia will maintain sea control. Although the bulk of this conflict has played out ashore, sea control enables supply and maneuver, including an advance towards Odessa. The best Ukraine can hope for is sea denial. NATO can support Ukraine’s fight for sea denial by providing mines, anti-surface cruise missiles, and scouting assets.

Ukraine successfully attacked Russian ships unloading armored vehicles in the port of Berdyansk. One LST sank at the pier and two others sortied, possibly damaged. It is unclear whether this attack was with ballistic missiles, drones, or something else, but it demonstrates the creative spirit of the Ukrainian Navy. This attack temporarily denied sea control to the Russian Navy and imposed costs on their ability to reinforce their siege of Mariupol. Improving Ukraine’s ability to deny Russia sea control will support the Ukrainian resistance along the coast.14 Although Ukraine might not be able to prevent another landing, these capabilities would enable Ukraine to impose serious costs on the Russian Navy. With the Bosporus Strait closed, Russia cannot reinforce the Black Sea Fleet. Enough ship losses will not only help Ukraine, but also help protect NATO’s Black Sea members.

LCDR Jason Lancaster is a Surface Warfare Officer. He has served at sea aboard amphibious ships, destroyers, and a destroyer squadron. Ashore, he has worked on various N5 planning staffs. He is an alumnus of Mary Washington College and holds an MA in History from the University of Tulsa. His views are his own and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

References

[1] British Ministry of Defense (2022, April 6). Russian Attacks and Troop Movements. London, United Kingdom: Twitter. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/DefenceHQ/status/1511640825549279233/photo/1

[2] Mongilio, H., & Lagrone, S. (2022, February 25). Russian Navy Launches Amphibious assault on Ukraine. USNI Blog. Retrieved from https://news.usni.org/2022/02/25/russian-navy-launches-amphibious-assault-on-ukraine

[3] Lagrone, S. (2022, February 24). Russian Navy masses 16 warships. USNI Blog. Retrieved from https://news.usni.org/2022/02/24/russian-navy-masses-16-warships-near-syria

[4] Mongilio, H. (2022, February 22). Turkey Closes Bosphorus, Dardanelles Straits to Warships. USNI Blog. Retrieved from https://news.usni.org/2022/02/28/turkey-closes-bosphorus-dardanelles-straits-to-warships

[5, 11] Hughes, W. (2018). Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

[6] Ponomarenko, I. (2022, January 4). Ukraine to get at least 3 Mark VI boats in 2022. Kyiv Independent. Retrieved from https://kyivindependent.com/national/ukraine-to-get-at-least-3-mark-vi-boats-in-2022/

[7] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2000. Oceanography and Mine Warfare. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9773

[8] Ralby, Ian and Zaliubovsky, Leonid, (2022, March 25), New Heights of Russian Hypocrisy and Unlawfare in the Black Sea. Retrieved from: https://cimsec.org/new-heights-of-russian-hypocrisy-and-unlawfare-in-the-black-sea/

[9] Woodward, S. (1992). One Hundred Days, The Memoirs of The Falklands Battle Group Commander. London: Harper Collins.

[10] Ponomarenko., I. (2021, March 15). Ukraine’s navy acquires first Neptune cruise missiles. Kyiv Post. https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/ukraines-navy-acquires-first-neptune-cruise-missiles.html?cn-reloaded=1

[12] Warner, B. (2019, January 10). Mark VI Patrol Boats Sail 500 Nautical Miles in Record Transit. USNI Blog. Retrieved from https://news.usni.org/2019/01/10/mark-vi-patrol-boats-conduct-long-pacific-transit

[13] Mongilio, H. (2022, March 4). U.S. Officials: Russian Forces Keeping Forces Ashore For Now, Odessa Amphibious Assault Still Possible. USNI Blog. Retrieved from https://news.usni.org/2022/03/04/u-s-officials-russian-forces-keeping-forces-ashore-for-now-odesa-amphibious-assault-still-possible

[14] Sutton, H.I. (2022, March 25). Satellite Images confirm Russian Landing Ship sunk at Berdyasnk. USNI Blog. Retrieved from https://news.usni.org/2022/03/25/satellite-images-confirm-russian-navy-landing-ship-was-sunk-at-berdyansk

Featured image: Russian Black Sea Fleet landing craft approach Crimea during an exercise Sept. 11, 2012, about two years before Russia took the peninsula from Ukraine. (Credit: Russian Defense Ministry)

This is what I understand as the origin of the term you used “jury rigged.” The pejorative “jerry rigged” came into use during WWII referring to poor quality. The phase probably evolved to “jury” because it’s not consider polite to refer to Germans as “jerries” anymore. I don’t know how the word “jerry” came into use referring to Germans. That’s the subject of another etymological deep dive. This old English teacher learned a lot reading your article.

Jerry came from British slang for chamberpots. They called them jerries because their helmets looked like chamberpots.

The phrase ‘jury-rigged- has been in use since at least 1788.[2] The adjectival use of ‘jury’, in the sense of makeshift or temporary, has been said to date from at least 1616, when according to the 1933 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of the English Language, it appeared in John Smith’s A Description of New England.[2] It appeared in Smith’s more extensive The General History of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles published in 1624.[3]

“Jerry was a nickname given to Germans mostly during the Second World War by soldiers and civilians of the Allied nations, in particular by the British. The nickname was originally created during World War I.[13] The term is the basis for the name of the jerrycan.

The name may simply be an alteration of the word German.[14] Alternatively, Jerry may possibly be derived from the stahlhelm introduced in 1916, which was said by British soldiers to resemble a chamber pot or Jeroboam.[15][16]”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_terms_used_for_Germans#Jerry

Above comment got posted before I finished filling in my information.

This analysis has been done before….

https://blog.usni.org/posts/2019/05/28/developing-a-black-sea-strategy