Regional Strategies Topic Week

By Ehud (Udi) Eiran

A Small Role to Play

Facing regional animosity since it was created in 1948, Israel evolved into a small regional power in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean. It deflected armed opposition to its existence in six major wars (1947-1949, 1956, 1967, 1968-1970, 1973, 1982) and multiple low-intensity armed clashes. Though it does not admit it publicly, it is probably the only nation in the region with nuclear weapons. It is further able to contain recent military challenges posed by the more effective non-state challengers, such as Hamas and Hezbollah.

The Israeli Navy, however, has played a relatively small role in Israel’s strategic posture over the years. Israelis generally did not view the sea as a source of threat, in part, due to the limited naval capabilities of their foes. A military doctrine that called for swift ground force action meant that even conflicts that had a maritime spark led to an Israeli resolution through an attack on the ground rather than the sea. The rise of the air force, especially since it played a crucial role in Israel’s swift victory in the 1967 war, left the navy as a secondary actor. The navy’s victories during the 1973 war, against the backdrop of initial failures on the ground and in the air, was still not enough to resurrect the navy’s status nor dim the public notion that the war as a whole was a national and military trauma. This state of affairs created a vicious circle in which no navy officers were promoted outside of the service. Indeed, 21 out of 22 Israeli Chiefs of Staff rose from the ground forces, and one from the air force.

The navy’s marginal role allowed it, perhaps paradoxically, to transform itself rather dramatically a number of times within a few decades. Initially it relied on a small number of frigates and destroyers, mostly older ships that Britain used during the Second World War. Other vessels included torpedo boats and landing crafts. Severely underfunded, the navy also trained, during its first decades, civilian crafts, to serve under its command in case of a war. By the early 1970s, the force transformed itself by focusing on French and Israeli-made fast corvettes. Though inferior to their Egyptian and Syrian foes, these boats performed most effectively during the 1973 war. By the 1980s, Israel had deployed some two dozen of these corvettes.

The late 1960s also saw a transformation in Israel’s small navy SEAL unit (Shayetet 13). Israel’s occupation of the Sinai Peninsula and one side of the Suez Canal created a longer maritime boundary with its largest foe at the time, Egypt. The protracted war of attrition between the two (1968-1970) created multiple opportunities for the SEALS to hone their capabilities in seaborne ground assaults. In the following decades, the unit emerged as perhaps Israel’s top combat special operations unit.

Israeli Naval Transformation

We are now in the midst of a third Israeli naval transformation, and probably the most dramatic one. For the first time in the navy’s history, it is assuming a role at the heart of at least two core Israeli national interests: dealing with an existential aspect of the challenge posed by Iran, and securing Israel’s energy supplies. For at least two decades, Israel viewed an Iran armed with a nuclear weapon as its primary security threat. Alongside an effort to curtail the Iranian nuclear project, it seems that Israel is preparing a second-strike capability for the day Iran will acquire an atomic weapon. Since 1999, Israel has acquired nine Dolphin and Dakar class conventional submarines, and by 2020 has commissioned six of them. Produced in Germany, it is largely believed that they could carry cruise missiles with the capability of delivering a nuclear weapon, though Israel never admitted that it has this capability, nor, as noted, that it has any nuclear weapons at all.

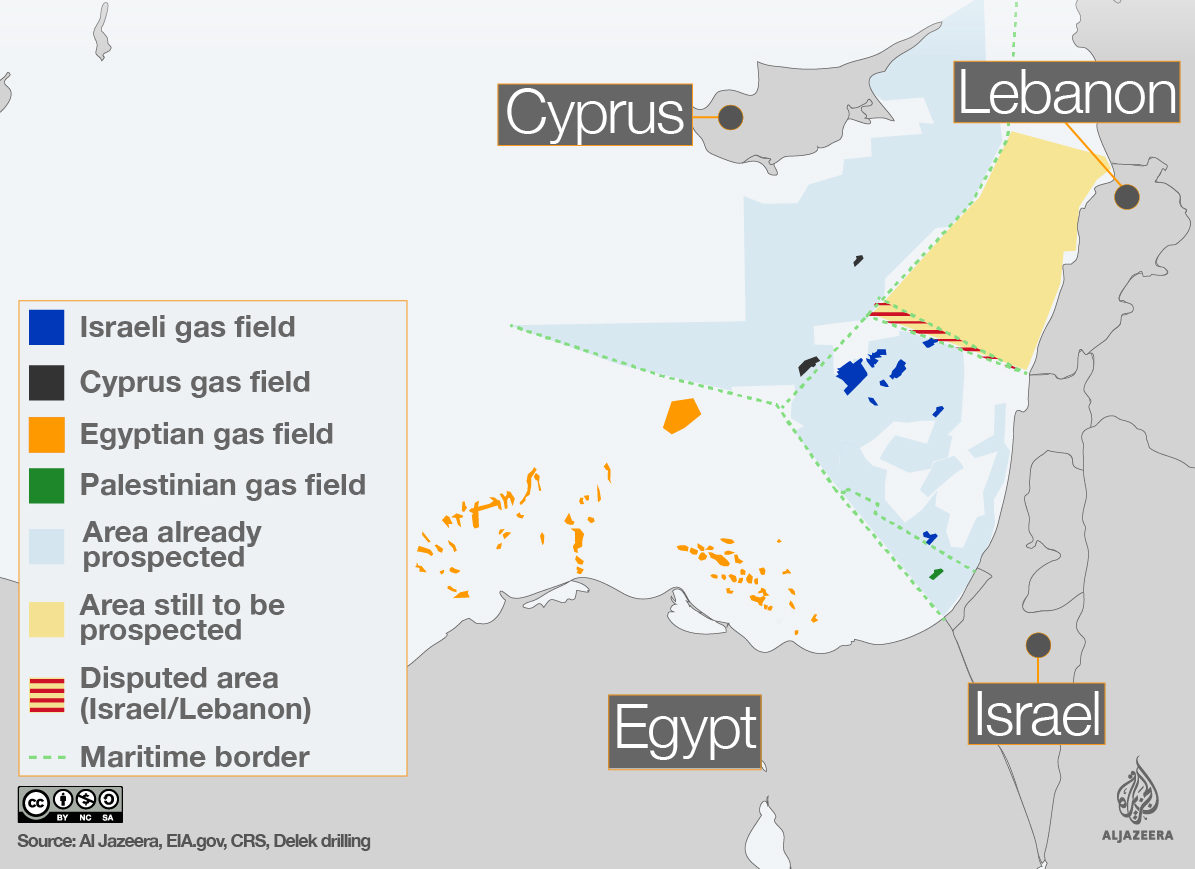

The second task that propelled the navy is the defense of Israel’s maritime energy assets. Starting in the late 1990s, Israel began to discover natural gas fields in its exclusive economic zone in the Mediterranean Sea. A 2010 discovery of the massive Leviathan field secured Israel’s energy independence for decades to come. By 2019, some 64 percent of Israeli energy was produced from its seaborne gas. The massive gas depots also allowed for exports to regional actors (Jordan, Egypt ,and possibly the Palestinian Authority), and serve as a basis for an alliance with Cyprus and Greece which includes a plan to lay a pipe that will deliver the gas to Europe.

However, the major fields of Tamar and Leviathan are close to Israel’s maritime boundary with Lebanon, and some other crucial facilities (such as the Tamar gas rig) are near the maritime boundary with Hamas-controlled Gaza. Although many of the assets are outside Israel’s territorial waters (but in its exclusive economic zone) and indeed are partially owned by non-Israeli corporations, the government decided in 2013 that the Israel Defense Force – in effect, the navy – will be made responsible for their protection. The new responsibility led to further naval procurement of four Sa’ar 6 corvettes from Germany.

The significant expansion of the naval force created opportunities for graft. For the first time in Israeli history, a former commander of the navy is likely to be indicted for bribery related to the deals. Other suspects include close associates of Prime Minister Netanyahu, which led to public calls, including by numerous former military leaders, to investigate his role in the navy-related bribery case.

Significant Maritime Developments

Two other developments highlighted the navy’s emerging significance. First, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, or at least its armed manifestations, was largely relocated from the land-locked West Bank, to the Gaza Strip, on the Mediterranean shore. Since 2007, Israel has been blockading the region, with much of the effort directed at preventing sea access. One recent indication of the centrality of the maritime security arena, was the revelation that Israeli intelligence penetrated Hamas’ maritime unit. In a dramatic escape, a senior officer in the unit defected to Israel in July 2020. Finally, Israel has mounted an effort to block supplies to its non-state foes such as Hamas and Hezbollah. This effort includes interdiction of vessels carrying arms hundreds of miles away from Israeli shores. For example, in 2014, Israeli naval forces boarded the Klos -C, a ship carrying arms from Iran to Hamas in Gaza, and brought it to Israel.

Israel’s Maritime Future

Looking forward, the Israeli Navy is facing a number of challenges. First, if the tensions with Iran, which manifest themselves in occasional air strikes in Syria, will expand, the navy may be called to further develop capabilities to reach Iranian shores. Israel is 1,500 km away from Iran, and the sea is an attractive route to access the Islamic Republic. Israel’s recent normalization of its relationship with the UAE and Bahrain might also make future Israeli naval deployments in the Arabian Gulf easier. There is also talk of a possible Iranian naval station in Syria, which may bring the maritime conflict closer to home.

Second, Israel has been developing a military alliance with Greece and Cyprus. In light of emerging tensions between the two and Turkey, mostly in the maritime domain, Nicosia and Athens might expect Jerusalem to deploy naval assets in a show of support. Israel has never fought alongside an ally, and has been very careful to avoid any military commitment to others, and so a Hellenic expectation could force it to review its policies. Either way, even the shadow of a possible conflict with Turkey is expected to provide further significance to the Israeli Navy.

Finally, the signals of American retreat from the region allow other maritime powers to operate in the Eastern Mediterranean more freely. A Russian naval presence off the shores of Syria, and the occasional visit of Chinese vessels, suggest that the Israeli Navy should get prepared for an environment that has a larger number of, and more powerful, naval platforms. These could constrain the freedom of operation of the Israeli Navy in the future.

Ehud (Udi) Eiran is a Visiting Scholar, Department of Political Science, Stanford University and an Israel Institute lecturer, Department of Political Science, UC-Berkeley. He is a retired Israeli army officer, and a former assistant foreign policy advisor to the prime minister.

Featured Image: An Israeli Navy ship during a major exercise held in the Red Sea off the coast of Eilat, March 2016. (Photo via Israeli Defense Force spokesperson)

Thank you for your informative concept. We can learn many things from this. American Bangla Newspaper.

About nonsense regarding nuclear ballistic missile capabilities on Israeli submarines…often discussed is a cruise missile launched from the oversized 25″ torpedo tubes.

Shocking error…