The High Seas Fleet and the PLAN: Striking Similarities in Strategy, Force Structure and Deployment

The first part of this series examined the nearly identical origins, and dismal, early combat histories. This second installment compares the equally similar strategy, operational art, and force structure, and concludes with observations on the PLAN can avoid the fate of the High Seas Fleet. Read Part One here.

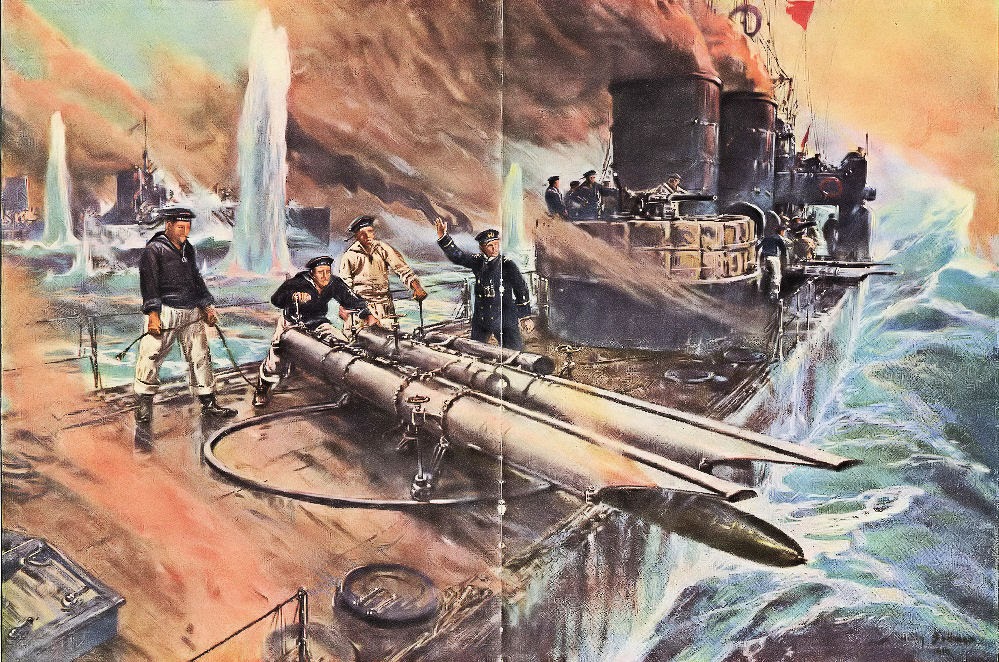

Both new fleets entered their identifiable “blue water” eras with similar strategies, operational concepts and tactics. The German High Seas Fleet retained robust coastal defense force structures even as its focus moved to the maritime space outside its own near abroad. This dual aspect of coastal and blue water operations was a key element in German strategy that was designed to defeat Great Britain’s Royal Navy (RN). High Seas Fleet architect Admiral von Tirpitz believed that a German Navy 2/3 the strength of the RN would be sufficient to defeat the British Navy in a battle if waged in German terms. Tirpitz envisioned drawing a portion of the RN into battle in the North Sea, but reasonably coast to German bases where torpedo craft (surface and subsurface), minefields and even shore batteries on advanced locations such as Heligoland Island might support the High Seas Fleet. German naval historian Holger Herwig suspects that Tirpitz never intended to attack Britain, but hoped that “British recognition of the danger posed by the German Fleet concentrated in the North Sea”, would “Allow the Emperor to conduct a greater overseas policy.”[1] The possibility would always exist that if Great Britain still defeated the German Navy in battle that it would be too damaged and perhaps, “Find itself at the mercy of a third strong naval power or a coalition (France and Russia).[2] Herwig also suggests that other would-be maritime powers might be inspired by Germany’s example and perhaps convince those nations to seek Germany as an ally. To achieve these ends, Tirpitz in effect attempted to create the early 1900’s equivalent of an Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) zone in the Heligoland Bight of the North Sea.

Evidence suggests that the PLAN is following a similar strategy. The Chinese are well on their way to building a very credible, regional naval capability.[3] The PLAN’s emphasis on operations within the Chinese defined “first island chain” seems to mirror Tirpitz’s focus on decisive battle in the North Sea. There is no evidence to suggest the Chinese are planning to launch an aggressive naval war against the United States, but are building naval forces sufficient to convince the United States and other would be opponents that the risk involved in combating such a force will entail significant naval losses. As Germany acquired the island of Heligoland in 1890 in order to secure the naval approaches to its significant ports from blockade, China is seeking to control and expand islets in the South China Sea in order to create a buffer zone around its sea lines of communication with its primary hydrocarbons supply sources in the Persian Gulf. Control of the South China Sea would also support potential military operations to place Taiwan under Communist Chinese control. Tirpitz thought his fleet would prevent Britain from considering a preemptive attack on Germany, as it had done on a nascent Danish Navy at Copenhagen in 1805. China appears to be creating its own A2/AD network to similarly deter U.S. action against the People’s Republic in the event of conflict over Taiwan, or contested islands in the South and East China Seas. Like Great Britain a century ago, the U.S. today must consider, “whether the U.S. Navy in coming years will be large and capable enough to adequately counter improved Chinese maritime forces while also adequately performing other missions around the world.”[4]

Although it is clearly building a “blue water” fleet that includes aircraft carriers, capable surface ships and submarines, the PLAN also maintains large forces of missile-armed littoral combatants analogous to the large German light forces of the early 20th century. China also has a much more powerful equivalent to the German shore batteries in the form of the Anti-ship Ballistic Missile, but this weapon does not yet appear to have been successfully tested against a moving target at sea.[5] With the bulk of its blue water fleet concentrated in home waters, and supported by similarly-based aircraft, submarines, land-based missiles and light naval forces, China has deployed a naval force structure remarkably similar to that of Imperial Germany. It appears focused on the control of its immediate sea zone and intended to deter the maritime hegemon from interference in its growing global economic, political and possible military activity.

There are some trends to suggest some of the new blue water PLAN units will deploy beyond the first island chain and operate in regular deployments abroad as the U.S. Navy has done since 1948.[6] Such deployments are fraught with peril if unsupported by a large global naval support structure and close allies. Admiral Graf von Spee’s crack cruiser squadron was deployed overseas at the German Pacific colony of Tsingtao (now the Chinese city and naval base of Qingdao) in 1914, but Tirpitz otherwise kept the heavy units of the High Seas fleet almost entirely in home waters for deterrence and potential combat against the Royal Navy. A future Chinese von Spee might wreak havoc on shipping and naval forces in the Indian Ocean or Red Sea, but would also be, “a cut flower in a vase, fair to see, yet bound to die” as Churchill said of the German commander.[7]

A Similar Potential for Catastrophic Failure

Both navies also share similar traits that eventually led to catastrophic failure in war for the High Seas Fleet. Admiral von Tirpitz based his strategy for victory against the Royal Navy on superior technology and highly trained personnel as well as specific numbers of capital ships. German warships were slower, had smaller guns and more austere in accommodation than their British counterparts, but had better gunnery optics, had thicker armor, and would prove more survivable in combat thanks to superior internal subdivision. German naval personnel were also expected to be more technically expert and better disciplined than their RN equivalents. This entailed adopting some of the harsher attributes of the Prussian Army to the naval service rather than forging a unique German naval culture to compete with that of the RN, who was the “motherhouse” for a multitude of world navies including those of the United States and Imperial Japan. Looking back in 1929, Germany’s official naval historian Admiral Eberhard von Mantley described the German naval culture of the Hohenzollern period as, “A Prussian Army Corps transplanted on to iron barracks.”[8]

The PLAN is likewise inured with the culture of a non-naval organization. The Communist Party of China plays a role in the Chinese navy similar to that played by the Imperial hierarchy in Hohenzollern Germany. The political work within the Chinese navy was once described as the “lifeline” of the service and essential to its support from the Chinese Communist Party.[9] The current commander of the PLAN, Admiral Wu Shengli, has long had close ties to the Communist Party through his father who was a Red Army political officer and governor of Zhejiang. Admiral Wu may also have had close ties to future Chinese President Jiang Zemin, who served as Shanghi Party Secretary when Wu was Deputy Chief of Staff for the Shanghai naval Base in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Like the support from the Chinese Communist Party, the Kaiser’s patronage, support and favor toward the Hohenzollern German Navy was that force’s connection to the German ruling elite and they budgetary support that connection supported.

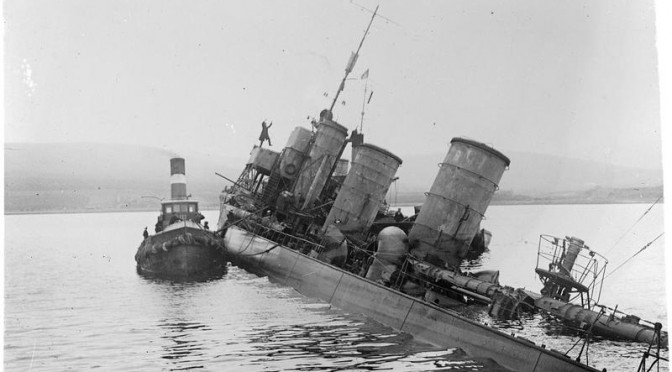

Naval historian Norman Friedman has suggested that one of the great flaws of the Hohenzollern fleet is that it was built without a clear strategic objective in Germany’s overall national military strategy.[10] Admiral von Tirpitz was very effective in assembling political and public support for a large fleet of capital ships, but when war did occur he did not have a defined plan as to how this very expensive fleet would be used. Friedman also points out that the German General Staff also no idea of what to do with the High Seas Fleet and that neither naval nor military leadership ever exploited its potential until late in the war with the U-boat campaign, which did not involve Tirpitz’ heavy surface units. German naval officers, especially those of senior rank also had little or no combat experience in 1914 against which to measure their operational performance at the outset of war.

While the Chinese have long planned on using naval forces to support the potential reclamation of Taiwan, and to protect vulnerable littoral areas bordering the Chinese state, their construction of larger warships such as carriers and large surface combatants has wider and more uncertain strategic ends. The PLAN and Chinese Army/Air Force elements can certainly dominate the South China Sea and its immediate surroundings in the event of a major Pacific War for a significant period of time. Would it be possible, however, for the PLAN alone to venture further afield to break likely distant blockades of Chinese hydrocarbon supplies and trade with a core fleet of “two aircraft carriers, 20-22 AEGIS like destroyers and 6-7 nuclear attack submarines?”[11] Like Tirpitz fleet of a century ago, an enlarged PLAN is strong enough in its own backyard, but risks considerable losses if it ventures away from bases and meets the combined strength of US and allied joint forces. This “prestige” element of the PLAN, like the High Seas Fleet, may be equally lacking in full strategic assessment as was its German counterpart. In addition, senior PLAN officers, like their High Seas Fleet counterparts from 1914, lack combat experience in war at sea.

Dr. Friedman suggest one other potentially chilling possibility when he references German historian Volker Berghahn’s claim that the German General Staff and aristocratic establishment may have seen war as a means of preventing the rise of a Center left Reichstag as a political check against traditional Prussian authority.[12] A war was seen by military and Prussian establishment leaders as a means of rallying the increasing working class around national objectives and recreating the unifying environment that produced the German Empire at the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War.

China’s stagnating economy, which slowed to 7.4% in 2014, a low figure not seen in 25 years, and the results of that change on the average Chinese citizen, has the potential to cause similar global unrest.[13] The Communist Chinese essentially made a bargain with Chinese citizens in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square riots. It would “deliver stability and prosperity” in return for continued loyalty and support of the Communist Party. The party has kept that promise for the last quarter century and delivered a 20 fold increase in the average income.[14] With this economic tide now cresting and perhaps beginning to recede, might Communist leaders seek to rally the Chinese public to international and security issues in order to distract from a looming economic downturn and maintain its control over the Chinese state? It is interesting to note that belligerent Chinese rhetoric on its South and East China Seas claims, and associated land reclamation efforts accelerated as economic advances waned. Could Communist leaders resort to more aggressive international efforts in order to preserve their rule as some historians have suggested Hohenzollern Germany did in 1914?

U.S. writer Mark Twain is reputed to have said, “History dos not repeat itself, but it sometimes rhymes.” The development of the PLAN over the course of the Cold War and especially the last twenty five years seems to rhyme very closely with that of the Hohenzollern High Seas Fleet. There are, however, some comforting differences. China is not nominally ruled by a mercurial Kaiser and has no Admiral von Tirptiz that is fully disconnected from other state organs of national security planning. It is not likely planning actual war with the United States or its close Pacific allies. That said, whether in mitigation of internal economic issues or paranoia over its seaborne hydrocarbon supply routes, China has engaged in a direct challenge to U.S. maritime superiority not seen since the Soviet Union created a global navy in the early 1970’s. While the Soviet effort was in the context of a wider Cold War, the Chinese maritime buildup has taken place in what has been a zone of relative peace since the end of the 1970’s.

No nation, or group of nations has denied China’s rise to the very top of world economic indicators, or its right to build whatever military establishment it desires. The crux of the problem is China’s aggressive bid to use elements of maritime power to close off sections of heretofore international waters. It is similar to the Communist state’s past land-based activities such as seizing Tibet and engaging in punitive expeditions against Vietnam. Like Hohenzollern Germany, another land-based power looking to move seaward, China fails to comprehend the dangers in aggression directed toward powers dependent on the free flow maritime trade. China would be well served to turn its naval expansion program toward less provocative ends.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD candidate in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941.

[1] Holger Herwig. The Luxury Fleet, The Imperial German Navy, 1888-1918, Abington/Oxon, UK and New York, Routledge Library Editions (reprint), The First World War, 2014, p. 36.

[2] Ibid.

[3] http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/will-china-have-a-mini-us-navy-by-2020/

[4] Ronald O’Rourke. China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress”, Congressional Research Service, Washington D.C., 01 June 2015, p. ii.

[5] Ibid, p. 6.

[6] http://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-9.pdf, p. 3.

[7] Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis, 1911-1918, New York, Free Press/Simon and Schuster, 2005 edition, p. 177.

[8] Herwig, p.120.

[9] http://www.idsa-india.org/an-jan00-7.html

[10] Norman Freidman, Fighting the Great War at Sea, Strategy, Tactics and Technology, Annapolis, Md, Naval Institute Press, 2014, p. 22.

[11] http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/will-china-have-a-mini-us-navy-by-2020/

[12] Friedman, p. 21.

[13] http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-gdp-growth-is-slowest-in-24-years-1421719453

[14] http://www.institutionalinvestor.com/blogarticle/3347789/blog/a-generation-after-tiananmen-china-blends-amnesia-and-assertiveness.html#.Vbrq9PbbLIU

This raises the question, would a democratically elected Congress in China support expanding the Navy or would it look askance at diverting funds from other priorities as the Reichstag often did? Have the NPCC or PCC even held a PLAN focused event?

I agree that would be worth further exploration. I believe that the PRC Central Military Commission still has only one naval officer (Wu Shengli).

Nice article, but a bit devoid from reality. (1) The U.S. Navy has basically been protecting “Chinese seas” since the 1940’s and its time for them to protect these sea lanes themselves. The U.S. has technically been bankrupt since the Kennedy Administration. Time to stop the American commercial shipping protection subsidy to China.

(2) Noting that the Chinese navy has no combat experience, neither does the U.S. navy. History is one thing, practical experience another. What battle fleet has the U.S. navy engaged in the last 20 years? One Iranian frigate?

(3) The Chinese do not have a Great Britain only a few hundred miles away. The U.S. is across a very large ocean. And Taiwan (which I believe will eventually merge (reunify) with the mainland) and Japan don’t really have large “battle fleets” to get in their face. So, where’s the immediate threat to China?

(4) If you listen to the Chinese, they are going slow, and are in no rush. Like Putin and Russia, they can do little things over a long time to get what they want. The U.S. can only pull back.

(5) Who says China’s neighbors really care about Chinese naval expansion? They are really consumer manufacturing, export-oriented societies with insignificant naval assets. And while they are modernizing those assets, they haven’t grown their naval assets to a sufficient level where, as a group, they can pull their collective weight.

So, the article is a nice thought piece, but I don’t believe it provides a real comparison which can inform naval or national strategy.

I enjoyed this read, although i would also liked to have seen a comparison between the Prussian General Staff and the Chinese equivalent regarding their navies. You have some references to Prussian Navy leadership contributions, but in this time-period the key strategic and operational level decision making was all being made in the (army) General Staff – who cared not for blue water agendas. How does this compare to PLAN?

Thanks again.

Good question. There is only one Admiral on the central Chinese military committee, so one could assume that naval influence is fairly low, as it was in the case of the Kaiser’s Navy’s influence on the Prussian/Imperial German Army. Lyle Goldstein and Andrew Ericcson have both written on this topic at some length and generally say that China’s political leadership likes naval expansion, but desires to keep it in check. It should also be remembered that both Goldstein and Ericcson are translators and not naval strategists by training. I will have to further explore this question, as I really do not have a good answer at this time.