The Diplomat has recently brought us a debate on international law – centering on the legality of military intervention on behalf of Taiwan during a conflict with the PRC. Zachary Kech kicked off by proposing that Japan’s recent reinterpretation of Article 9 of their Constitution to permit collective self-defense could allow for Japan defending Taiwan in the event of an attacked from China. This was followed by Julian Ku arguing that intervention by any nation on behalf of Taiwan against the mainland would be illegal since Taiwan is neither definitively recognized as an independent nation nor a United Nations member. Michal Thim quickly refuted those claims in an article, which is followed again by Julian Ku coming back with some clarifications on personal opinions and reiterates the original argument. Finally, Michael Turton and Brian Benedictus co-authored a somewhat convoluted argument that actually Taiwan’s unsettled status as an independent nation makes military intervention acceptable.

With no disrespect meant toward the authors, the merits of discussing this point are mostly academic. Though the debate may be stimulating to those with an interest in the topic and some might learn more about the subject of international law as a result of it, it has little to no bearing on practicality.

One of the key questions present in all of the articles is if Taiwan is an independent nation or an extension of mainland China and how international law views each situation. Clearly arguments can be made in support of both positions or else we would not have so many articles written about it in the past couple of weeks, but does it really matter? Whatever semantics used to describe relationships with Taiwan or China, the U.S. has active relationships with both of them.

According to the Office of the United States Trade Representative, China is currently the U.S.’s second largest goods trading partner with $562 billion in total goods trade during 2013 and Taiwan is currently the 12th largest with $64 billion in 2013. Would any of this change if the United Nations passed a resolution stating Taiwan was not an independent nation and officially a part of the larger mainland China? Of course not. Money, and more importantly national interests, will conquer over semantics any day.

Whether the U.S. or Japan would defend Taiwan if China decided to repatriate the island through military force should have nothing to do with semantics and everything to do with strategic interests. The strategic basis for protecting Taiwan or not is neither the subject of this article nor the debate at the Diplomat which inspired it. This article makes no comment as to should or would other nations protect Taiwan, but instead discusses could they.

There is so much talk about international law in the debate. International law, as opposed to simply international norms and conventions, has been in vogue since the fighting of two world wars and the founding of the United Nations. Why? Because law has an absolute and moral feel about it. If you are breaking the law then you are doing something wrong and others have a moral obligation to stop you. If you are following the law then you are doing something right and others have a moral obligation to support you. This grossly oversimplifies the complexities of international relations. Decisions are made to promote strategic national interests and all nations are not necessarily playing by the same moral and ethical code. In the domestic concept of law, you have a like peoples under a recognized government authority with enforcement power. This does not seamlessly translate to the international stage of co-equal governments with differing interests and no central authority with absolute enforcement power.

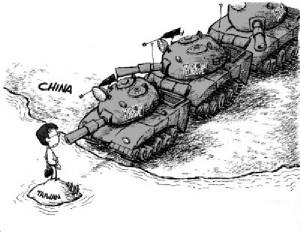

If China decided tomorrow to repatriate Taiwan with military force and the U.S. and Japan intervened, would they be protecting a sovereign nation from an invading force or helping to liberate a people from a government they do not want? This semantic difference might matter when deciding what article of the United Nations charter you are going to try to use for propaganda to gain support for your cause or generate opposition for your enemies or what the victor who writes the history will use to justify their actions in the history books. But in all practicality, nations should base their use of force on national strategy and not semantics.

LT Jason H. Chuma is a U.S. Navy submarine officer currently serving as Navigator and Operations Officer onboard USS SPRINGFIELD (SSN 761). He is a graduate of the Citadel, holds a master’s degree from Old Dominion University, and has completed the Intermediate Command and Staff Course from the U.S. Naval War College. He can be followed on Twitter @Jason_Chuma.

The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

As Kenneth Waltz said about anarchy in the international system…